'A Loaf of Bread, a Container of Milk and a Stick of Butter'

What we can learn from the cartoons of Jim Simon.

Hello and welcome to a new edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter! We’ve got a big one lined up for you this week.

We’re starting with a longread about animator Jim Simon and his groundbreaking studio Wantu Animation. Even if you’ve heard of him, you may learn something new here. After that, we’ll run down the week’s top headlines from around the world.

As always, this newsletter goes out every week — and you can sign up for free to get it delivered by email each Sunday:

With that said, let’s get started.

Wantu Animation vs. the world

The United States has a long history of racism, exclusion and stereotyping. Its cartoons have never been immune to that.

Back in 1943, the NAACP wrote that the cartoon Coal Black held its characters “up for derision” and told Warner to withdraw it. A few years later, the organization argued that Disney’s Song of the South helped “to perpetuate a dangerously glorified picture of slavery.” Those films were far from the first, or the last, to meet criticism like this.

Even in a climate that marginalizes Black voices, though, those voices fight back. It’s crucial to remember these stories — because forgetting also marginalizes. It scrubs hard-won victories from the record. It leaves more space for oppressors in the history books, and less for the oppressed.

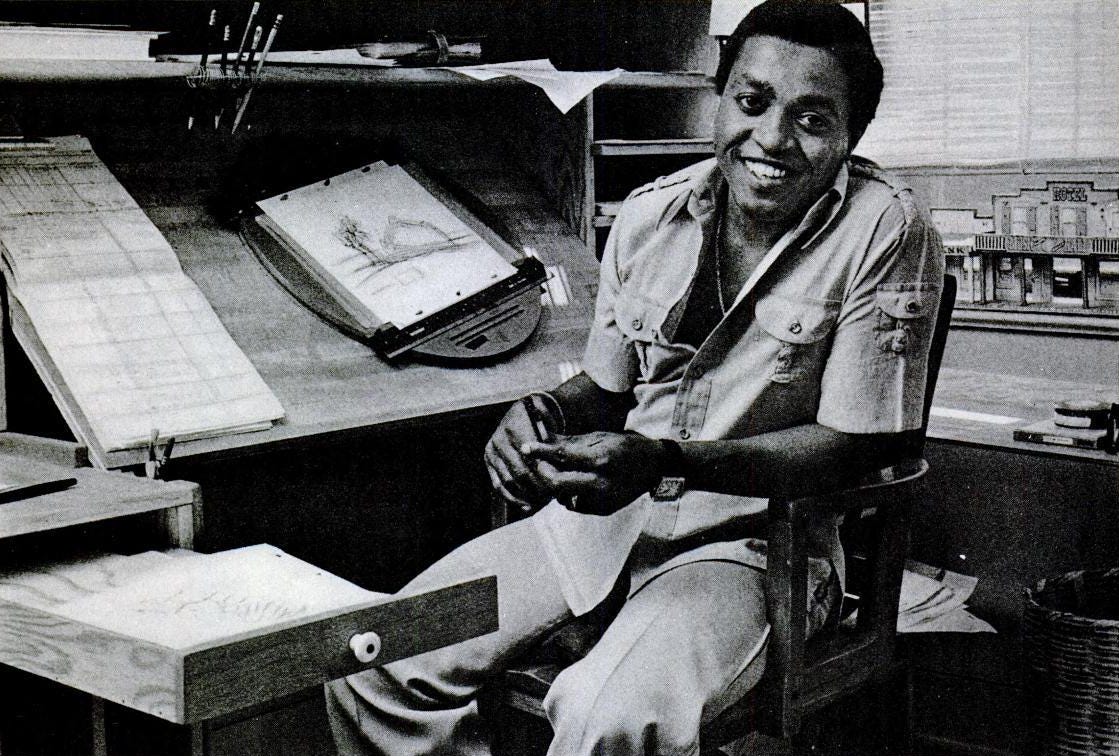

Jim Simon is not a household name today, and that’s thanks to forgetting. The press once dubbed him “the Black Walt Disney.” He didn’t embrace that label, but he did run his own animation studio and inspire generations with his cartoons. His impact is best illustrated by a little film called Bread, Milk and Butter:

Bread, Milk and Butter comes from Sesame Street. It first aired in November 1972, around three years into the show’s run. And it continued to play through the early 2000s. Along the way, it became one of the series’ best-known cartoons.

The short stands out right away. Its story is a naturalistic take on the everyday life of millions of kids. Its scratchy, expressive design blends with a style of animation that’s at once limited and free-form. The look and the jazz-funk soundtrack channel the spirit of the time in a way that few cartoons did. And it centers Black characters who look and act nothing like the stereotypes from old Hollywood cartoons.

Bread, Milk and Butter was one of Jim Simon’s very first films as a director. It was to be the beginning of a much longer, much more complicated journey.

Starting points

As the story goes, Jim Simon joined the animation industry in 1967. His time at the School of Visual Arts landed him a job at Manhattan’s Paramount Cartoon Studios, managed for a time by Ralph Bakshi. The studio closed not long after Simon joined.

And so he followed Bakshi to another company, working on the Spider-Man TV cartoon as an assistant animator. “I was turning out so much work, they had to promote me,” he told Millimeter Magazine in 1975, “because I was earning more money than some of the full-fledged animators.”

After being bumped around the industry like so many workers at that time, Simon finally landed at Tee Collins Inc.

Collins was the first Black artist to found an animation studio in New York, as we wrote a few months back. By 1970, Tee Collins Inc. was reportedly “the only Black owned and operated [animation] studio on the East Coast.” Its work on Sesame Street was foundational to the series. Collins himself was a famously gentle and patient artist, and he took Simon under his wing.

“It was under Tee Collins’ tutelage that Jim Simon was able to fill in the details he still had to learn about filmmaking,” according to Filmmakers Newsletter.

Simon struck out on his own in the early 1970s. He dreamed of being a full-fledged animator — a job position that still eluded him. “I figured the only way I was going to become an animator was by making myself an animator,” he told Millimeter.

And so Simon approached Sesame Street about doing his own shorts. The company said that he needed a studio to apply. Here’s what he did next:

I borrowed $250, hired a lawyer to set up a company, did a couple of story boards on my own but sticking with the Sesame Street vein of thinking, and marched back up there. And right off the bat, they bought four of the five boards that I had brought up.

As a result, Wantu Animation was born in 1972. Simon said that the name was “Swahili for beautiful,” and that its logo was “an African symbol of new birth.” He set up shop in Manhattan.

At least four shorts attributed to Wantu aired on Sesame Street that year, one of which was Milk, Bread and Butter. The others don’t have confirmed titles, but are known as Snow Day, I’m Six Years Old Today and Train #2. All four are wonderful — and all four continued to run for more than three decades.

The boom years

Wantu Animation took off fast. The 1970s were a time of explosive growth for children’s educational television, and Jim Simon found his niche in it.

He continued to work for Sesame Street, but also its sister program The Electric Company. Like Wantu itself, both shows were native to New York City in an era when California ruled the cartoon roost. Simon called New York little more than “an advertising town” in the world of animation — but these shows gave him access to large and dedicated audiences.

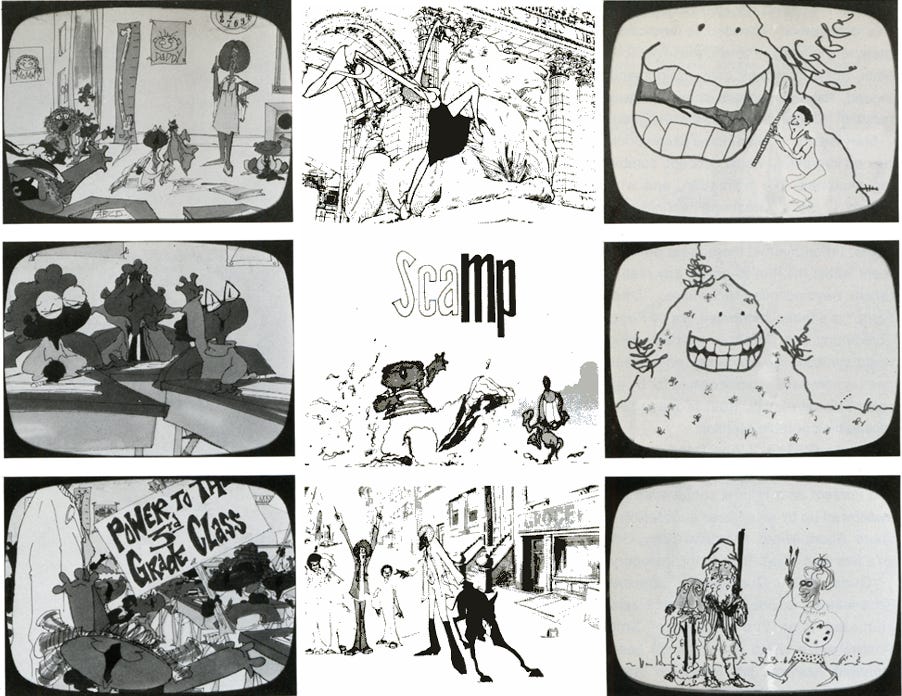

His work won awards, too. Wantu and its signature style, which the magazine Black Enterprise described as “Afro-Cubistic realism,” started to clean up at the local ASIFA-East festival. Its film The Strike, for the Black Psychiatrists of America, won at both ASIFA-East and the USA Film Festival. Wantu’s work also made waves at Animafest Zagreb and took home a major prize from Advertising Age.

One of Simon’s most acclaimed cartoons was Hey Diddle Diddle for The Electric Company. It’s a high point for his character design sensibility. “No eyes on them,” as he put it, “but you believe them when they’re moving.”

Within five years, Wantu had gross sales in the ballpark of $400,000 annually, not adjusting for inflation. Its staff was primarily Black. According to historian Tom Sito, Wantu had started as “the first all-African-American animation studio.” Simon only began to hire non-Black talent once he ran into a shortage of animators.

Simon was succeeding in an America very different from the one that had birthed Coal Black. But he was up against many of the same hurdles and prejudices. Black Enterprise recounted the story of a “network vice president, who in 1974, told Simon that Black children weren't considered a significant programming audience.” It summed up Simon’s feelings on the animation industry at the time:

It frustrates him, as a Black animator, to see white-oriented companies giving the same coloration to all Black characters, using crows to represent Black people or recreating animated versions of Stepin Fetchit. He turned down the chance to work on Bakshi’s film Coonskin, and has been disappointed by most of the Black-oriented animated films and shows so far produced.

All of this would set the stage for Wantu’s biggest and most ambitious project yet.

Sesame Street and The Electric Company were progressive shows, with diverse casts and staffs — and frequent appeals to unity. But the New York State Education Department went even further with its own educational series in the mid-1970s. Vegetable Soup was a powerful cry for diversity, confronting prejudice by name. Some of its ideas are only now becoming mainstream.

“The melting pot idea is no longer viable,” producer Yanna Kroyt Brandt said at the time. “Many people don’t want life to be a melting pot. They want to be a part of the whole, yet they want to maintain their own ethnic and cultural identities. The aim of the program is to help children learn to live together in appreciation of the common humanity of different peoples.”

Vegetable Soup was a big project, and animation was core to it. Tee Collins Inc. handled a few segments, but Wantu was behind the bulk. In the first season alone, Simon oversaw “13 cooking spots for which Bette Midler did all the voice tracks, and also 48 thirty-second breaks.” Many of those won at ASIFA-East. Wantu also did both of the show’s psychedelic title sequences (watchable here and here).

Simon’s color use and character design jump out at you in Vegetable Soup. Like Bread, Milk and Butter, they channel their era in a bold way — at a time when some studios were looking old-fashioned. “I used a variety of colors to help convey and reflect the many colors of America,” he said in 2017.

Vegetable Soup has never been properly restored, but it’s in the public domain — and every episode is available online via the American Archive. While it’s basically unknown now, it can’t be overlooked in the history of 1970s animation, any more than Sesame Street or The Electric Company can be. The same applies to Wantu’s work for it.

Rise and fall and rise

Wantu Animation was a hotly tipped studio by the late ‘70s. It had been a wildly prolific decade for Jim Simon.

“We’ve turned [out] approximately fifty films this year, about three, sometimes close to four minutes a week,” he said in 1975. Its work on Vegetable Soup’s first season alone amounted to nearly an hour.

Then, hoping to break into longer projects like TV specials and feature films, Simon moved Wantu Animation to North Hollywood around 1977. He took out a loan of $47,000 to make it happen. But he was diving into a world much more competitive than the animation scene in New York City.

All was not well for Simon. A profile in the San Diego Union-Tribune later put it like this: “on the business side, people stole his work and lied to him. He faced jealous competitors, and he felt his company ran into a glass ceiling.”

Yanna Kroyt Brandt said that she “lost track of Jim Simon … when he moved to LA.” Information is spotty about his career during this period. He reportedly worked on a long list of projects, including the Brown Hornet segments for Fat Albert. The Museum of UnCut Funk states that he later animated a title sequence for Soul Train.

Simon started working for bigger studios as an animator, character designer and layout artist. And he managed projects in Ireland and Asia. IMDb starts to credit him as an overseas supervisor from the late ‘80s onward, a job he held on shows like Doug.

Meanwhile, a small listing in a 1987 edition of the Los Angeles Times suggests that one “Wantu Enterprises” had filed for bankruptcy. Eleven years later, that studio name reappeared on a VHS project called Tell Me Who I Am, directed by Simon. That was around the time he burned out.

“After leaving the Hollywood animation scene and that entire world it entailed,” Simon later wrote, “I found myself so emotionally drained that I was unable to bring myself to lift a pencil.”

Simon became an alcoholic, abandoning art for a decade. But he bounced back in 2008, when he rediscovered his passion through painting.

Since then, people have started to remember what Wantu achieved during the ‘70s — to a degree. Many of Simon’s cartoons are still unavailable to the public, or they currently float around the internet uncredited to him. It’s not even clear which Soul Train opening he animated. Simon did a retrospective on his career for Sacramento’s ArtStreet back in 2017, but no public recordings exist.

So, that’s it. In the fight between Wantu Animation and the world, Wantu didn’t lose. Bread, Milk and Butter by itself cements the studio’s place. But Wantu didn’t win, either. It was marginalized at the time, and that continues today in the writing of animation history. People are still debating whether Song of the South should be on Disney+ — seemingly no one is trying to release missing Wantu films like The Strike.

If there’s one thing we can learn from Jim Simon’s films, though, it’s this: the work matters anyway. It was unforeseeable that Bread, Milk and Butter would stick with two or three generations of kids, but it did. Hey Diddle Diddle and the Vegetable Soup spots touched people, and some of those people still remember, even if they don’t know who made them. Simon’s impact was felt, even if it wasn’t known.

Headlines around the world

Demon Slayer continues to dominate

Japan’s highest-grossing film isn’t Titanic or Spirited Away — it’s Demon Slayer: Mugen Train. Few expected the film’s historic success, to the tune of $363 million in Japan alone, when it premiered last October. If anything, its international performance has been even more surprising. It’s already the world’s biggest-ever anime feature.

Mugen Train broke records at the American box office this week, netting the country’s largest anime opening since 1999 — despite its R rating. The film rose to first place this Saturday and Sunday. Meanwhile, the series upon which Mugen Train is based hit 500 million views on China’s YouTube competitor Bilibili this week. The Demon Slayer brand appears to be unstoppable.

HBO Max orders local animation in Latin America

HBO Max rolls out in Latin America next month, and the service is spending big in the region. It’s begun 33 original productions within Latin America — a number set to rise above 100 during the next two years.

Many of those are live-action. But at least one confirmed project, Frankelda’s Book of Spooks, will be animated. This is a stop-motion series produced in Mexico City, originally shown as a pilot in 2019. Frankelda already looks fresh and vibrant, and it’s a hopeful sign that HBO Max plans to invest in Latin American animation. You can see more via Animation Magazine.

Soyuzmultfilm teams with Russian comics giant

Lately, not a week goes by without an update from Soyuzmultfilm. The Moscow studio, established as a state-run animation workshop during the Soviet era, has moved aggressively as a private company in recent years. By all appearances, it’s trying to position itself as Russia’s answer to Disney.

On Friday, Soyuzmultfilm revealed a new licensing deal with Bubble Comics, Russia’s largest comics publisher. Soyuzmultfilm is adapting Bubble’s popular comic series Coolix, among others, as cartoons — and Bubble will produce comics based on Soyuzmultfilm’s catalog of classic films. Coolix was announced in March, but this deal expands the partnership between the two companies.

Last word

Thanks for reading! We hope you’ve enjoyed.

This week, we’ve switched up the title of the news section to better reflect its goal. Covering global animation news, including stories never reported before in English, is a growing interest of ours. We plan to expand beyond even the regions we’ve already covered — so stay tuned.

Finally, if you liked this week’s edition but haven’t yet signed up, why not give us a shot? We’ve been at this since mid-February, and we’re very thankful to the readers who’ve stuck with us. There are many more issues to come — and you can catch them all right from your inbox:

Until next week!

Bravo. Loved this episode and had a strong desire to sit and talk with Jim Simon about what must be a very bitter sweet - yet rich - experience. I certainly had a strong sense of my own finitude seeing that later photo of him.