Everything Is Anime

Plus: global animation news and the words of Satoshi Kon.

Happy Sunday! It’s time for another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. The plan goes like this:

1 — on the universal influence of anime.

2 — the animation newsbits of the week.

3 — Satoshi Kon on a film’s parts versus its whole.

New here? We publish Thursdays and Sundays. Paying subscribers receive both, but it’s free to sign up for our weekly Sunday issues. Get them right in your inbox:

That’s that — let’s go!

1. What isn’t anime?

Anime is on trend right now. Its impact is so widespread that it’s hard to know where to start.

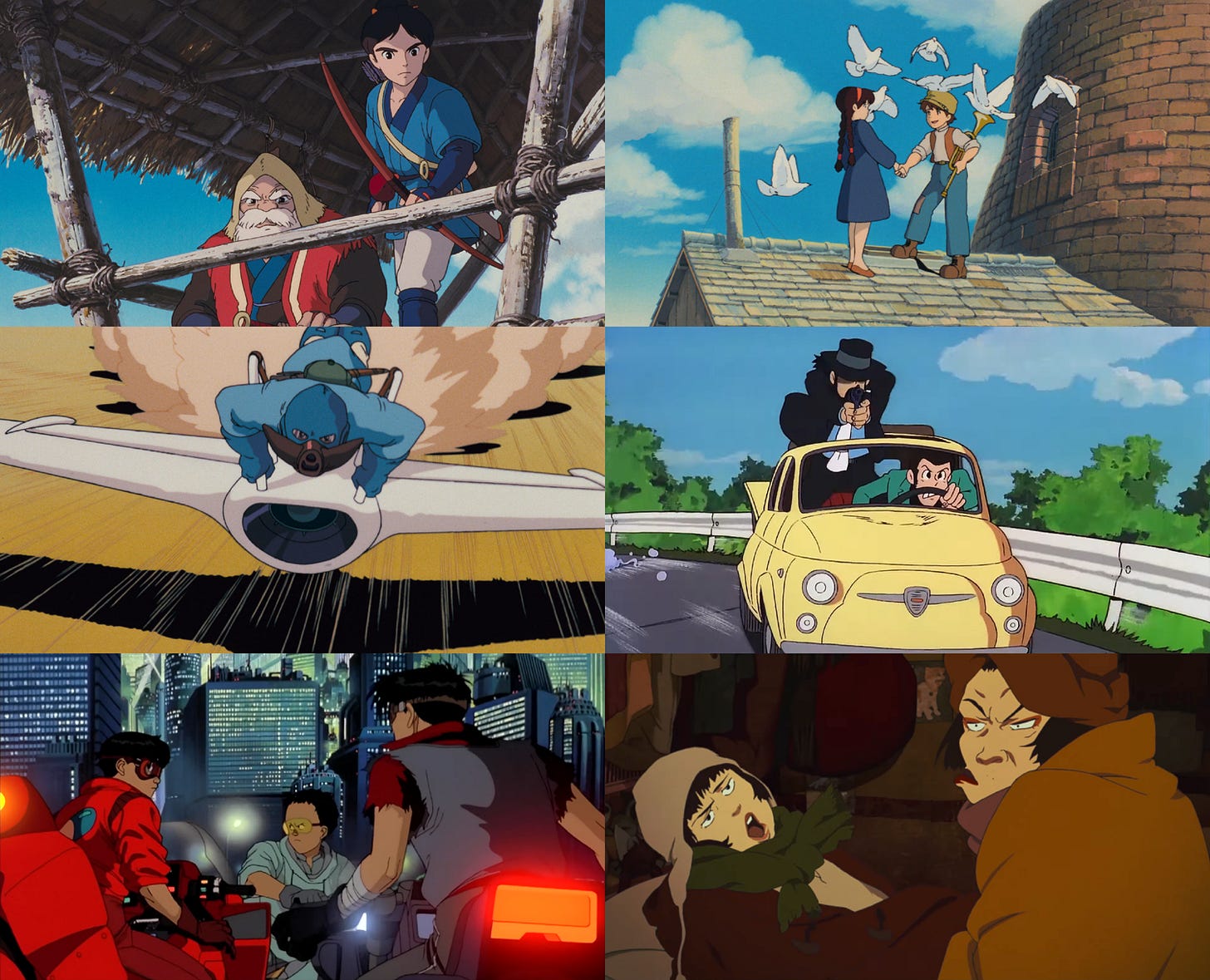

Amphibia’s recent finale referenced Gurren Lagann and used its theme as temp music. The Bad Guys and the new Puss in Boots movie both draw from anime — one protagonist in The Bad Guys was inspired by Lupin III and Sherlock Hound. And, a few months ago, the production designer for Turning Red said this:

For us, it was really cherry-picking what we loved because anime is a huge range. [...] So, we were on the whole spectrum of anime, we were just kind of picking, “We like this, and we like this, and we like this. Okay, now, let’s put it all in the pot and put it into Turning Red.”

It’s not just animated films and TV. Eleven in Stranger Things was heavily influenced by anime. Acura, Gucci and Chobani borrowed anime aesthetics in their recent commercials. Lil Nas X and the anime franchise Fate/stay have an ongoing flirtation.

Taking from anime feels modern — like it’s the latest thing. The director of The Bad Guys suggested as much in an interview last month, saying that the influence of anime helped to make his film “slightly different from what we usually see in animation in Hollywood, in the big CGI movies from Hollywood.”

It feels new. But is it?

Not exactly. As the magazine Keyframe pointed out a few years ago, the influence of anime predates the current moment. It touched Steven Universe, How to Train Your Dragon and Teen Titans — but predated them, too.

“In creating the flying sequences for 2002’s Lilo & Stitch, Director Dean DeBlois recalls drawing on [the] influences of films like My Neighbor Totoro and Porco Rosso,” reported Keyframe. And Lilo & Stitch itself was late to the party.

In fact, by that time, anime had been an overriding influence at Disney for more than a decade. The iconic animator Glen Keane said in 2010:

… it’s hard to ever separate the huge influence that Japanese animation has had on me. I was just in awe of Miyazaki’s work, and have emulated his sensitivity, his approach to staging. That had a gigantic impact on our films starting with Rescuers Down Under [1990], where you saw the huge Japanese influence on our work. That’s part of our heritage now, which we don’t back away from.

Anime has even informed Keane’s drawing — The Art of Wreck-It Ralph notes that he added “an anime flair” to the character Sergeant Calhoun. The look of Tangled has a lot of anime in it, too.

And Keane is far from the only Disney veteran of that era to cite anime as an influence. It was a hot topic at the company by the ‘80s and early ‘90s. TaleSpin’s co-creator Mark Zaslove once wrote, “I’d always felt that Hayao [Miyazaki] was lookin’ at our stuff […] God knows we were looking at his.”

Co-creator Jymn Magon agreed:

Mark’s right. We all owe a huge debt to Miyazaki. In fact, the day that Art Vitello was brought in to direct Gummi Bears [… he] said, “I want you to watch two movies before we even talk. Then you’ll know what is possible.” He showed me Nausicaä and Laputa... in Japanese! I didn’t have a clue what was going on, but I couldn’t get over the aerial scenes! I was an instant convert.

Then when I hired Mark a year or two later, I did the same thing — showed him Miyazaki. He was blown away, as well. Obviously it influenced us when it came time to create TaleSpin.

Even TaleSpin was a latecomer to anime, though. Before his rise to and fall from grace, John Lasseter was a young fan of The Castle of Cagliostro, showing it around California in the early-to-mid-1980s. “Technically, artistically, story-wise, this movie was a tremendous inspiration for me, and it had a profound impact on me,” he’s said.

One person who saw Lasseter’s copy of Cagliostro was the Disney artist Michael Peraza (The Great Mouse Detective). “When John Lasseter brought that film among others to show in the Disney theater I was really blown away,” he later wrote. In the end, Peraza successfully pitched the idea of changing The Great Mouse Detective’s final battle into a “sort of homage to the Miyazaki film.”

It’s ironic. Keyframe’s article quotes a Seis Manos writer as saying, “I wasn’t very into Disney [when I was younger]. I was like, ‘Screw those cute lions.’ ” He preferred anime. Yet, in 1994, a group of Japanese manga artists saw enough similarities between anime and Disney’s “cute lions” to pen an angry letter about it.

The Disney Renaissance was, in no small part, a product of anime’s influence. Toy Story couldn’t have happened without Cagliostro, either. Anime wasn’t yet mainstream in America, but artists already knew about it.

Which blurs the traditional battle lines between “anime” and “Western animation.” By the early ‘90s, a huge portion of the ideas in American cartoons came from anime and manga.

That was true beyond the confines of Disney and Pixar. As researcher Raz Greenberg has written, “The link between Batman: The Animated Series and anime is stronger than that of any other American show that came before it.” Its creators have spoken themselves about that influence, and were “well aware” that the Japanese outsource artists on Batman had worked on Akira and the like. They were fans.

It was a trend even outside animation. Todd McFarlane was “influenced by the gorier manga” and anime for his Spawn franchise. Frank Miller (Sin City) had started taking from manga by the early ‘80s. Both artists helped to define the ‘90s vision of “cool” — violent, dark, grim and stylish. It’s hard to leave Japan out of that discussion.

So it went for Hollywood’s live-action directors — and not just the Wachowskis, who modeled The Matrix on Ghost in the Shell. Guillermo del Toro has recalled “watching Japanese anime with Jim Cameron, because we used to show each other the latest anime back in the ’90s.” Cameron’s Terminator 2 borrowed heavily from Akira (one staffer remembered using an Akira scene “almost like a storyboard”).

As for del Toro, he’s readily admitted that anime appears in his films. “You can see the enormous love I have for all things Japanese in everything I do,” he said, citing directors like Miyazaki, Katsuhiro Otomo and Satoshi Kon.

Another devoted anime fan back then was Quentin Tarantino. “I love anime, but Quentin kept turning me on to anime I’d never seen before,” actress Chiaki Kuriyama (Kill Bill) once said. “His knowledge was amazing."

The influence of anime permeated American film and TV during the ‘90s and 2000s. It was in The Powerpuff Girls and Samurai Jack. It was in No Doubt music videos. Gorillaz was a British band, but it was hard to escape on American TV during the 2000s — and it was openly inspired by anime. (“I’ve watched that film [Castle in the Sky] so many times,” said the band’s artist Jamie Hewlett.)

Since then, anime’s influence has only grown — not just in America, but all around the world. By the ‘90s, anime was more popular in Europe than it was in the United States. Its biggest non-Japanese market for many years has been China. The global impact continues today.

All of this raises a strange possibility. For a long time, anime has been positioned as the next thing. Something fresh, new and here to change the status quo. Artists took from it to upgrade their work.

And yet this process has been ongoing for three or four decades. The world’s been taking from anime since at least the early ‘80s. Its influence has reached four generations, maybe five. Most of our reference points — new or old, foreign or domestic — tie back to anime in some way.

You start to wonder: what if everything is anime now?

The anime-inspired styles of The Bad Guys and Turning Red get contrasted against “typical” CG films, and it’s true that they don’t look like Toy Story. On another level, though, they’re new entries in a long tradition. Pixar, and by extension Hollywood 3D animation, is attached to anime at the root.

As Lasseter said in 1999, “When we have a problem […] we often watch a copy of one of Mr. Miyazaki’s films for inspiration. And it always works.”

That goes for Disney, too. Cartoon Brew recently dinged the upcoming Strange World for lagging behind its anime-inspired rivals — and sticking with “the long-established Disney house style.” But isn’t that style anime, too? Roger Ebert was accusing Tarzan of copying Miyazaki’s design sensibility by 1999, the same year that Mulan’s directors called Miyazaki “like a god to us.” Big Hero 6, Tangled and Frozen got even closer.

Today, Disney’s past and present are both entrenched in anime. Same with Pixar — and so much else. In fact, what art or culture is totally separate from it?

It’s worth wondering about. If everything is anime, then what?

Is anime a new status quo that will, one day, be upturned by films equivalent to My Neighbor Totoro and Akira — but in a style we can’t imagine yet? Will young, radical artists rebel against anime’s influence and find a new paradigm for their work?

Or is there no “next thing” this time, like when sound came to film?

We’ll have to wait and see.

2. Global animation newsbits

A giant of Russian animation, Leonid Shvartsman, has passed away at 101. It’s impossible to summarize his career here — we’ll return to the subject next week.

In Japan, a third storyboard teaser for the new film by Sunao Katabuchi (In This Corner of the World) has been released.

Check out the stills from the American series Lost Ollie, based on a book series by William Joyce. It’s created by Shannon Tindle (Kubo) and directed by Peter Ramsey (Spider-Verse).

The Ukrainian group Animatoriya is holding animation classes for children in Sumy. See pictures in this article.

The British stage production of My Neighbor Totoro has Jim Henson’s Creature Shop aboard to craft “the lifesize forest trolls, sprites and other spirits.”

In America, the Academy invited 397 people to become members, including 41 from animation — the most of any field. Lots of huge names like Michael Rianda and Sarah Smith, but a conspicuous one is Russia’s Anton Dyakov (BoxBallet).

Eurimages has infused €500,000 into Valemon: The Polar Bear King, a Norwegian-Belgian co-production with character designs by Peter de Sève (Ice Age).

Pakistan’s film The Glass Worker is causing an unexpected number of people on the Chinese internet to bemoan the state of their industry: “We lost to Japanese animation, then to American animation, and now we’re losing to Pakistan.”

Also in China, Anim-Babblers has an interview with Lei Xiao about his film Dogmatism. He says that it was mostly inspired by his own college experiences.

Lastly, there’s an impressive new trailer for the upcoming feature Diplodocus, a co-production between Poland, Slovakia and Czechia. The film is due 2023.

Thanks for checking out the issue! We hope you’ve enjoyed it so far.

Our last section today is for paying subscribers (members). Below, we look at a few words of wisdom from Satoshi Kon, the director of Perfect Blue and Paprika. He wrote about how the parts and the whole of a film interact — and how inexperienced artists often get the balance wrong.

Members, read on. We’ll see everyone else in the next issue!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.