‘It’s Unbelievable That We Actually Pulled It Off’

Inside 'The Inventor,' plus animation news.

Happy Sunday! We’re back with more from the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s the lineup:

1️⃣ Inside The Inventor with Jim Capobianco.

2️⃣ International animation news.

For those just finding us — it’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues. Get them weekly in your inbox:

And now, let’s go!

1: An impossible dream

For well over a decade, Europe has produced a lot of the world’s best animation. The volume is hard to believe, although not all of it reaches the mainstream. Ernest & Celestine has a global cult following, but great movies like Little Vampire and The Swallows of Kabul are obscure. There’s a revolution happening partly under the radar.

Visibly or not, Europe’s network of animation talent might be the best anywhere right now. Japanese and Hollywood studios increasingly draw on it. Even then, though, it’s rare to see an American director join this ecosystem to realize their idea the European way.

Yet that’s what Jim Capobianco did with his film The Inventor. After a well-received premiere at Annecy in June, it’s opening across the States on September 15.

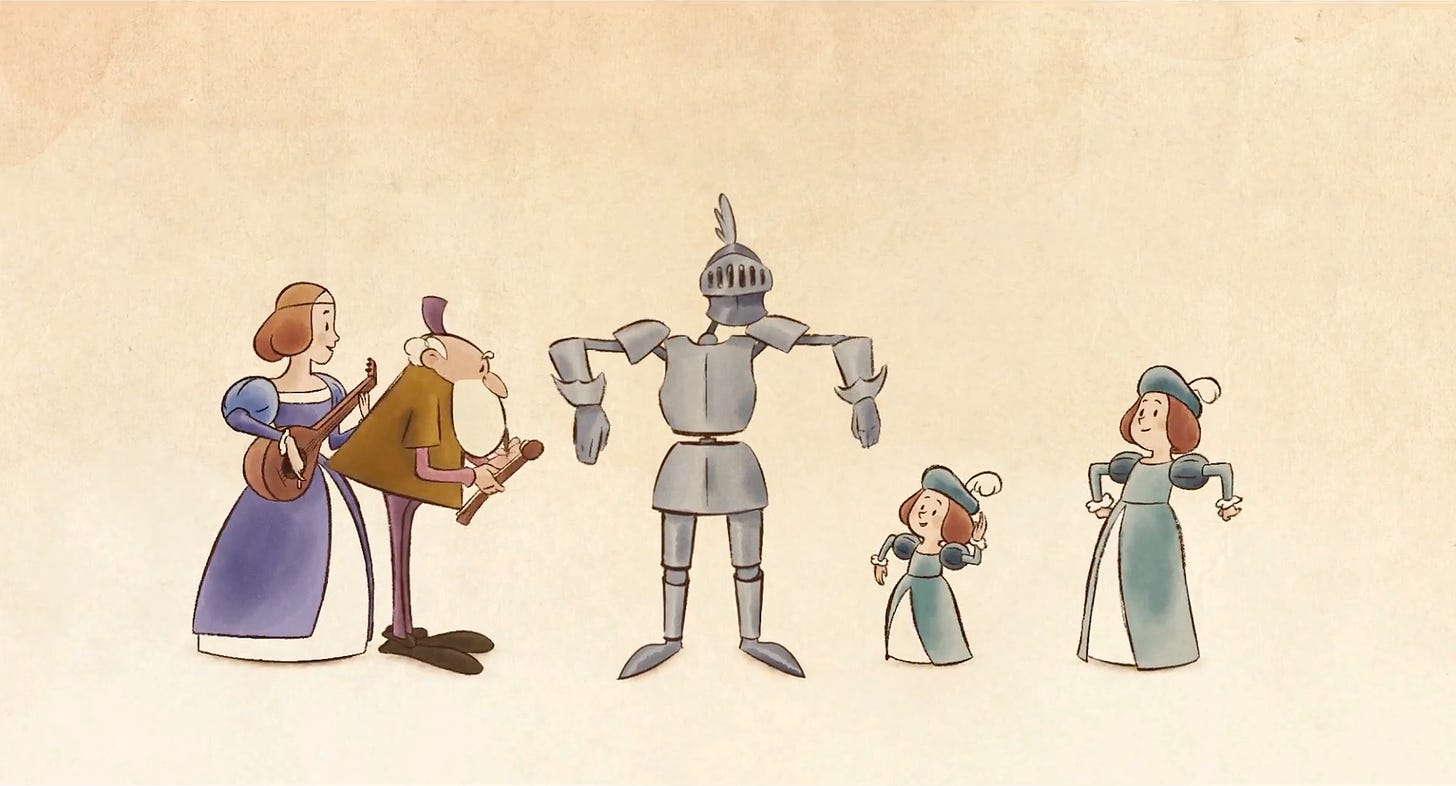

With The Inventor, Capobianco has woven a semi-historical, semi-fantastical story about the misadventures of Leonardo da Vinci in Italy and France. Leonardo works around kings and the Pope, dreaming up machines, hunting for life’s secrets and stealing cadavers. Stephen Fry plays the lead, with Marion Cotillard and Daisy Ridley in major roles. Having seen it ourselves, it’s a visually gorgeous and very funny film with its own identity. And it’s a cross between stop-motion and 2D animation, both parts impressive and assured.

Capobianco is a name in Hollywood. He has story credits on The Lion King and The Hunchback of Notre Dame. He worked as a Pixar story artist on Monsters Inc. and Inside Out, among others. Capobianco’s story work on Ratatouille, with Brad Bird and Jan Pinkava, was nominated for an Oscar. But he went to France and Ireland to make this dream project.

The whole unlikely process of The Inventor took more than a decade. As with most European animation, money was tight, and getting any was tough. The film doesn’t look or feel cheap, though: it’s fantastic. We wanted to know how they did it.

So, we asked Capobianco. He was kind enough to give us an in-depth look behind the scenes of The Inventor. This is process talk — about the endless journey from concept to completion, art and design, building a team and getting maximal results with minimal money. We’re very happy to share his insights and rare perspective.

The interview, edited for formatting, length and clarity, appears below.

Animation Obsessive: How long and how continuously did you develop the concept for The Inventor before it entered production?

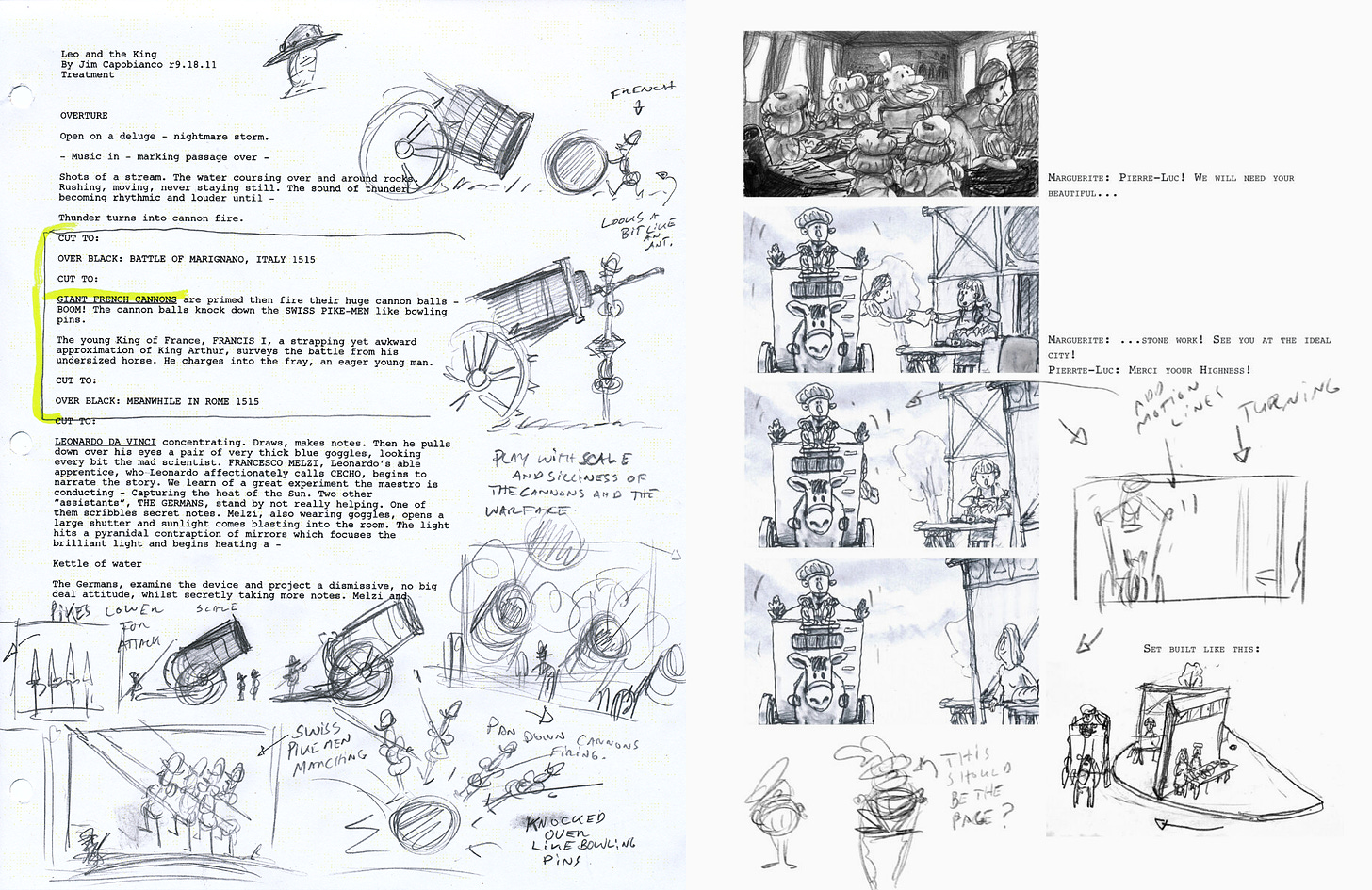

Jim Capobianco: I started working on an animated feature about Leonardo da Vinci, originally titled Leonardo and the King, around 2011. One of my early treatments is dated about then, so I have the evidence!

I’d made a short film called Leonardo that went around the festival circuit in 2009. It was during this that a mother, who’d enjoyed the short with her children, asked me if there were other animated films like this, both entertaining and about historical figures. I think UPA did a short about Raoul Dufy, and I’m sure there are others. But at that moment I couldn’t think of any, especially in the mainstream. So, I thought to myself, “Maybe I could create that.”

To me, that’s where this crazy idea to further explore my take on Leonardo da Vinci started to form. From there, it was another nine years until we went into production.

During that time, it was never continuous. I was working at Pixar, so I was focused on developing stories there until 2016. Then I left and directed the 2D on Mary Poppins Returns and created Philharmonia Fantastique. So, I was busy. But I’d find little snippets of time to keep writing, storyboarding, doodling and, of course, working with my co-producer Robert Rippberger to look for money and figure out how to set this up. There were so many dead ends, it really looked like it would never get made.

Seeing it complete, this isn’t a movie that would’ve been made in the Hollywood system, in theme or animation style. When did you realize you were going to take the project to Europe?

It’s funny; while Jan Pinkava and I were developing Ratatouille, we kept being told we were making the film with a European sensibility. I’ve always had a tendency to approach story and character a little differently than the usual “Hollywood” way. It’s just what I do, the way I think.

So, I created a story I wanted to see and tell. We originally peddled the film around the US, and Netflix was interested for a hot minute, at least to look at the script. Same with Apple. But, once they read it, they didn’t want it.

So many places didn’t see the humor or understand the approach, because that’s impossible to write. The story has a fair amount of dialogue, maybe too much, but a lot of its charm and humor come through the visuals. From the design and the way the characters move. None of that can be written, and every executive has a picture in their mind of a Pixar movie or, if they think in terms of stop motion (which I would guess most don’t), they are seeing Laika films.

I thought the best home would probably be in Europe — given its sensibility — but Robert and I weren’t locked into that. We would’ve made it practically anywhere someone gave us money to make it.

I’ve known Tomm Moore, Paul Young and Nora Twomey of Cartoon Saloon since I toured Leonardo around as they were touring The Secret of Kells. We even showed the films together in Santa Barbara. So, they’ve been part of the DNA of the LCU (the Leonardo Cinematic Universe, as my daughter calls it) since the beginning. They were instrumental in connecting us to people in Europe and giving us guidance.

We pursued making it fully in Ireland, on the western, weathery edge of the country near Galway, in the middle of nothing but sheep. Saloon told me that was crazy. For a time, Robert and I tried to set the film up in Italy with producer Federico Fiecconi and the late Riccardo Trigona. It seemed obvious, but it turned out that the Italians weren’t keen on a film about Leonardo da Vinci moving to France. As we learned, they kind of like to ignore that da Vinci ever left Italy.

I always saw France as a perfect place to set the project up, given that it’s about da Vinci in France and there’s tremendous animation talent there, but I never thought we could make it happen. Until it did happen, and rather quickly I might add.

Through Saloon, we got a meeting with Folimage in Valence, France. But they canceled on Robert after he flew from the States for it. So, Ross Murray, one of the original Salooners, felt bad about this meeting that he’d set up and suggested that Robert meet Ilan Urroz, the owner of Foliascope across the Rhône River.

Robert showed Ilan what we had of the film, the teaser and so on. Ilan was looking for Folia’s next film to follow No Dogs or Italians Allowed (2022), and he loved The Inventor. It was just perfect timing. He offered to jump off the cliff with us and, if you will, build the flying machine on the way down.

The Inventor looks fantastic, from the design to the stop-motion and 2D animation. How did you get such a polished, ambitious result with a (reported) $10 million budget?

The budget was even less, I believe. I have no idea how we pulled it off. Robert I don’t think took a salary. Alex Mandel, the composer, used some of his salary to hire a better orchestra.

If you look at our opening credits, there’s an embarrassing number of pre-film bumpers (something like 12), and I don’t know how many executive producers. But we needed all of them. We had a successful Kickstarter, which helped us finish the story animatic. We really looked in every seat cushion to find loose change to pay for this. Had friends and relatives add money here and there. Robert was really good at shaking the trees. Ilan as well was instrumental in knowing the French system of film support. He worked very, very hard with Robert to balance the books and work with the tax breaks. We managed it somehow.

We achieved the look on our teeny-weeny budget by planning. I’d designed Leonardo for the short with dot eyes and basic shapes; an M&M for his head, a cone for his body, two sticks for his legs and baguettes for his feet. All the other characters had to be designed with these simple principles in mind, which meant we wouldn’t have a lot of the face replacement or complicated armatures found in high-end films like Pinocchio, etc. There are perhaps a dozen, maybe fewer, camera moves in the entire film that used a physical moving camera, and a few others that were done digitally, so that saved money and time.

The film is shot mainly “on twos,” which many of the animators had to adjust to, since I guess most bigger-budget stop-mo is “on ones.” I’m not really a fan of ones; I find the animation too mushy. I even told Kim Keukeleire, our animation director, I didn’t care if the animation switched and mixed twos, threes, fours or fives, as long as it conveyed the performance and story properly.

She liked that I was flexible with this and the animators enjoyed the freedom they had to be broader. But it turned out not necessarily to be easier to animate that way for everyone. They had to relearn, adjust to a more “cartoony” technique of animation.

Being a story artist helped me tremendously. Our line producer, Kat Alioshin, created a ten-week board (the “big board,” as we called it) that listed the twelve stages. It was in the busiest traffic area, a kind of funnel from the offices and common area to the stages and workshops. Everyone passed by it. The board showed what shots were coming up.

As the production matured and I understood stop-motion better, I would look at this board and see what was going to be a problematic shot. Maybe it had multiple characters or a camera move, something I learned is complex and time-consuming. I would often come up with a new take on it, simplifying it. It would become a puzzle to think of a more efficient but interesting way of conveying the moment.

I would walk up to my co-director Pierre-Luc and tell him I had an idea about such-and-such shot. At first, he was really apprehensive, thinking I was going to make it more complicated. But soon he realized that, nine times out of ten, when I came up to him, I’d made the shot more economical and interesting and thus better.

So, I learned to work within my limitations and everyone else did, too. I love this quote from Orson Welles, “The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.” The film thrived on that ideal. The team was just amazing, probably the best team I may ever work with, and all their work is up on that screen.

Who were some of the key players in the stop-motion aspect, and how did they get involved in the project?

Number one would be our line producer Kat Alioshin. She was with the film since about 2016, when we made a little teaser that she helped to organize and find a crew for, mostly former Nightmare Before Christmas artists.

With the feature, Kat set up the production and moved to France for a year and a half. She made things run super efficiently with tools and systems she’d used in her time on many stop-motion films. Organizational ideas new to the French, who seemed more accustomed to looser productions, where each lead was responsible for their own schedule, etc. She changed that.

She’s also a total, lovable goofball, so she made the atmosphere at the studio fun. Organized Halloween parties, got confetti cannons for milestones, was always upbeat. I don’t think the French knew what to do with it. The crew loved her and she the crew. Happy crew, happy film. She made it all go smoothly.

Number two was Pierre-Luc Granjon, my co-director and now great friend. I had looked at his films as inspiration for The Inventor, but I never in my wildest dreams imagined I would meet him or have him co-direct with me. Ilan put us together, since he’d worked with Foliascope on The Tower. Pierre-Luc knows stop motion inside and out, so he was my guide and mentor.

He organized the film with Kat, creating the schedule of shots and figuring out what stages would be used, what sets would go on those stages and for how long. Helped in designing the sets so they’d be accessible to the animators. He was often the first to set up a shot and then he’d call me over. We’d discuss it, and many times I’d change it, but he always kept the production moving and warned me of difficult shots to film. He was an amazing collaborator. It was very much the cliché of us sharing a brain.

Number three: Kim “Kong” Keukeleire, our stop-motion animation director. Kim’s career includes animating on all of Wes Anderson’s films, even Asteroid City. She animated the alien in that film after hours and on weekends while on The Inventor. She also did a stint on Pinocchio right as we were gearing up.

But none of this stopped her from organizing the armature build, so that her animators would work with the best armatures, and so that those armatures would not be impeded by the costumes. She also assembled a wonderfully talented and diverse group of animators who brought amazing, subtle acting to very simply designed (perhaps deceptively so) puppets.

Hefang Wei handled 2D animation. She’s an amazing animation director herself. When she went on maternity leave, the really talented François-Marc Baillet took over.

Having lived with Leonardo for so long, I became a bit militant on getting his model right in 2D. Each animator seemed to draw him differently. Nose too big or too small, hat the wrong shape or in the wrong place, height too short. (Everyone draws Leo small, like an elf. He’s actually taller than Marguerite and even King Francis.) I really appreciated stop motion at that point, because the model never changes! But, in the end, Hefang got it and she would go over everyone’s drawings to keep him on model.

The 2D team were the unsung heroes of the project. We seemed to keep assigning them more work, moving things from stop motion to 2D, because 2D was cheaper to do. Even changing an entire sequence from stop motion to 2D during production. Later on, though, they asked if we could switch the film’s last shot from 2D to stop motion. It took some work on my part to make sure it was doable, and then some convincing that we could make it happen in our final weeks. But it was the right call: the film needs to end in stop motion.

Other contributors were the director of photography, Marijke Van Kets, who understood the older look I was shooting for. Marion Charrier, our set design supervisor, who took such pleasure in creating sets for French landmarks like Amboise Castle. François Cadot, the puppet supervisor, and costume lead Pauline Valls, who just made the most gorgeous-looking, rich, Renaissance clothing for the puppets with our tiny budget. Fabrice Faivre was basically a one-man technical director who handled everything from servers to Dragonframe glitches to camera insanity. He also eventually did what his VFX supervisor job was supposed to entail, overseeing the composite shots and making sure the rigs were removed and all the pieces fit together seamlessly.

My collaborator at the very end was Nicolas Flory, who co-owns Foliascope but was also the film’s editor and 2D supervisor. He wore many hats and brought a tremendous sense of control over all these areas, so I didn’t have to worry about them. Nicolas has a great sense of fun, too, which made the long days spent finalizing the cut very enjoyable. I’d often bring Jameson whiskey to our edit sessions, and he’d provide the 80%-plus dark chocolate.

The production was 50-50 women and men, and that included the leadership, which might have even skewed slightly in favor of women. I am pretty proud of that. We just had the most amazing team. I can’t stress how wonderful these artists are.

Your co-director Pierre-Luc Granjon has said that you were drawing from a variety of sources, including Rankin/Bass, Jiří Trnka and even Granjon’s own Four Seasons in the Life of Léon. Could you talk about how those inspirations impacted the film?

Yes, we did. As well as Karel Zeman’s Mr. Prokouk and King Lavra, Michael Bond’s Paddington series, Screen Novelties’ Elf and, to some extent, the work of Bill Justice and X Atencio at Disney. We even looked at A Charlie Brown Christmas and Bruno Bozzetto’s West and Soda. And at live theater stage design, for the creative stage transitions and stylized sets that leave a lot up to the audience’s imagination.

All of these references pointed to a simpler way to approach stop motion than something from Laika, Pinocchio or other modern stop motion. I find a lot of contemporary stop-motion design to be very busy. The characters and sets have a lot of detail, and the camera work is quite extravagant and complex. When I storyboard, I rarely add in camera moves. I don’t really think that way, and I find them too hard to draw. I lean toward old-Hollywood proscenium staging, focusing purely on how the frame and the image inside it tell the story, with very simple moves or none. So that the eye can rest on the characters.

Most of the above examples that inspired us had this more classic look, and were designed in a very economical but charming way. If you look at something like Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer from Rankin/Bass, the walls are gray, the props are gray and even the food is gray. The world is monochrome except for the characters, who just pop off the screen. Approaching the film this way focused everything on the puppets, the acting and the story. It also made the film economically doable while, at the same time, making it look like we’d spent a lot more money on it than we had.

It also feels like there’s a strong UPA influence here (Madeline, etc.). Was that a reference point?

Again, it goes back to deceptive simplicity. I funneled a lot of what I like in animation and even live-action films into The Inventor. I love UPA’s artistically bold use of design and the frame.

Of course, Marguerite and the four court ladies are directly influenced by Madeline. I like the design, but it conveys story. Marguerite is expected to take care of the children, so they’re a group and they’re dressed similarly. She’s meant to be with the children. However, she’s their mentor, and she’s taught them to be free-thinkers and -doers. They are all Madelines. They’ve subverted the expectations put on women in those days and thus freed themselves from the bonds that society shackled them with.

The UPA ideal is also about how much of the design is left up to the audience to project onto the art. The design of the characters and worlds is, to some extent, incomplete. This opens things up to the audience. Rather than being told a story, they’re asked to participate in its telling. Approaching the film with a UPA mindset of design allowed me to make it look a lot more expensive than it was.

What was it like working in the European co-production system compared to Hollywood?

In the European system, the director has a lot of control, whereas in the Hollywood system the producer has more control. So, once we got going, I pretty much had complete creative control. Except for budget and time. But, as one of the producers myself, I had to keep that in mind and I found it a lovely puzzle to figure out how to make these constraints work for the film, rather than as an impediment to the film.

The co-production setup limited how many Americans could be on the film, since they had to work in the European Union. It was partially the reason I needed to have a co-director, but, as mentioned earlier, that was a blessing. The budgets are smaller than in Hollywood because of the tax breaks and government funds you can tap into. It sets up a timeline for you, because you need to do X to unlock these funds before you can do Y.

There can be many entities to keep in touch with, figuring out what work and what percentage of the film will go to which co-producing country. Because that’s how you get funds; part of the film needs to be made in that country. So, our production was in France and post-production in Ireland. It’s a lot to juggle for the producers. Thankfully, we only had two countries involved. Tomm Moore would tell me how insane it was to balance all the co-producing partners on The Secret of Kells, where a lot of pieces of the film were made across several countries.

How does it feel to finally have The Inventor complete? What was your experience seeing the finished cut for the first time?

Well, it’s unbelievable that we actually pulled it off. There were many, many days when I didn’t think the film would get made, and I thought I was wasting my time. Even worse, wasting other people’s time.

The belief of all these wonderful people in the film made it a reality. Robert Rippberger, who stuck with the project from nearly its inception. Composer Alex Mandel, who worked on it for about as long, writing songs and score that might never have been sung or heard. Kat Alioshin, Ilan Urroz, Nicolas Flory, Foliascope. It wouldn’t have happened without meeting them, and especially without Ilan saying, “Oui! I want to make this!”

It took twelve years for it to become a reality, and it’s wonderful that it did. Seeing it at Annecy was surreal. With it done, I don’t know what to do with myself now. The film seemed like it was always there as a thing to do, and now there is nothing more to be done.

Lastly, how viable do you think it is for other American directors to take the same path you did, going to Europe to make feature animation?

It’s an interesting question. I really don’t know. Like anything, it’s about the people you connect to, the people you know. As an American, you need a European producer to pitch at Cartoon Movie, so that’s a hurdle. You also have to be willing to make a film for less than $10 million — more like $8 million or less.

I don’t even know if I could pull this off again. I would need the same team, and that’s never in the cards. What I do know is that I would love to see more independent or semi-independent animated films made in the USA.

I’m always fascinated by live-action directors like the Coen brothers, or Wes Anderson, who can make these quirky and not-necessarily-mainstream films within the Hollywood system. I’d love to be able to do that with animation (and I guess Wes Anderson does that, too). We do need more boundaries being pushed and hurdled, more risks being taken, more voices and, frankly, more of the craft of animation and its possibilities being experimented with. You know, what you guys talk about in this newsletter, I feel this is missing from animation today, especially in the US.

When Walt Disney started out, he was an independent struggling to get Snow White made and distributed. Obviously, times have changed, but there are always ways to circumvent the status quo. If I learned anything from 12 years of nurturing The Inventor — from a zygote of an idea to a young adult getting kicked out of the nest to live its own life, good or ill — it’s that perseverance can pay off.

I mean this in hindsight, of course. It could very well have not paid off. But the only way to get here was to persevere. And it’s only because that damn genius of an old man wouldn’t leave me alone.

Our thanks to Jim Capobianco for taking the time to give us such a deep interview. It’s been a thrill to learn more about The Inventor — which opens in US theaters on September 15. You can find screenings via its official site.

2: Newsbits

The British developer Chris Mitchell is making a stop-motion adventure game narrated by comedian Adam Buxton.

German animator Lotte Reiniger is getting more of her work restored and screened — several of her ‘50s silhouette films are hitting France in October. See a trailer via Catsuka.

A rare and expensive book on Mexican animation history, The Lost Episode (El episodio perdido, 2004), is now free to download via ResearchGate. We bought a physical copy last year, and it’s informed a number of our articles to date.

In Canada, Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron made its international debut at TIFF. Guillermo del Toro introduced it by saying, “We are privileged enough to be living in a time where Mozart is composing symphonies. Miyazaki-san is a master of that stature.” It opens in America on December 8 (English trailer here).

Meanwhile, in Japan, there’s talk that Miyazaki is already back in the studio and planning more films.

The American outlet Vulture wrote about the fall of Rotten Tomatoes — “erratic, reductive and easily hacked.”

England’s Aardman released the trailer for Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget.

In Ecuador, the site Primacias reports on the trend of “nearshoring” that Hollywood began during the pandemic: outsourcing more animation work to Latin America rather than traditional strongholds like Korea. Workers in Latin America are calling it an opportunity to grow the sector — as long as it leads to more local, original films and series.

One more from Japan: a controversial tax that poses a huge threat to the anime and manga businesses is set to go into effect on October 1. Animenomics has an explainer.

In China, the Kongzang Animation & Comics Archive has unearthed and published rare documents about the very first Shanghai International Animation Film Festival.

Lastly, we wrote about one of the most acclaimed stop-motion scenes ever shot: the torment of Neklan in Jiří Trnka’s Old Czech Legends.

See you again soon!

The Inventor looks like a breath of fresh air in American theatrical animation so great to see it get extensive coverage from the Animation Obsessive Staff.

I can't wait to see this one!