Learning the Real Lessons from Ghibli

Plus: news.

Welcome! It’s time for a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and this is the agenda:

1) Inside the filmmaking and writing of The Glassworker.

2) Newsbits.

With that, let’s go!

1 – “Don’t give up”

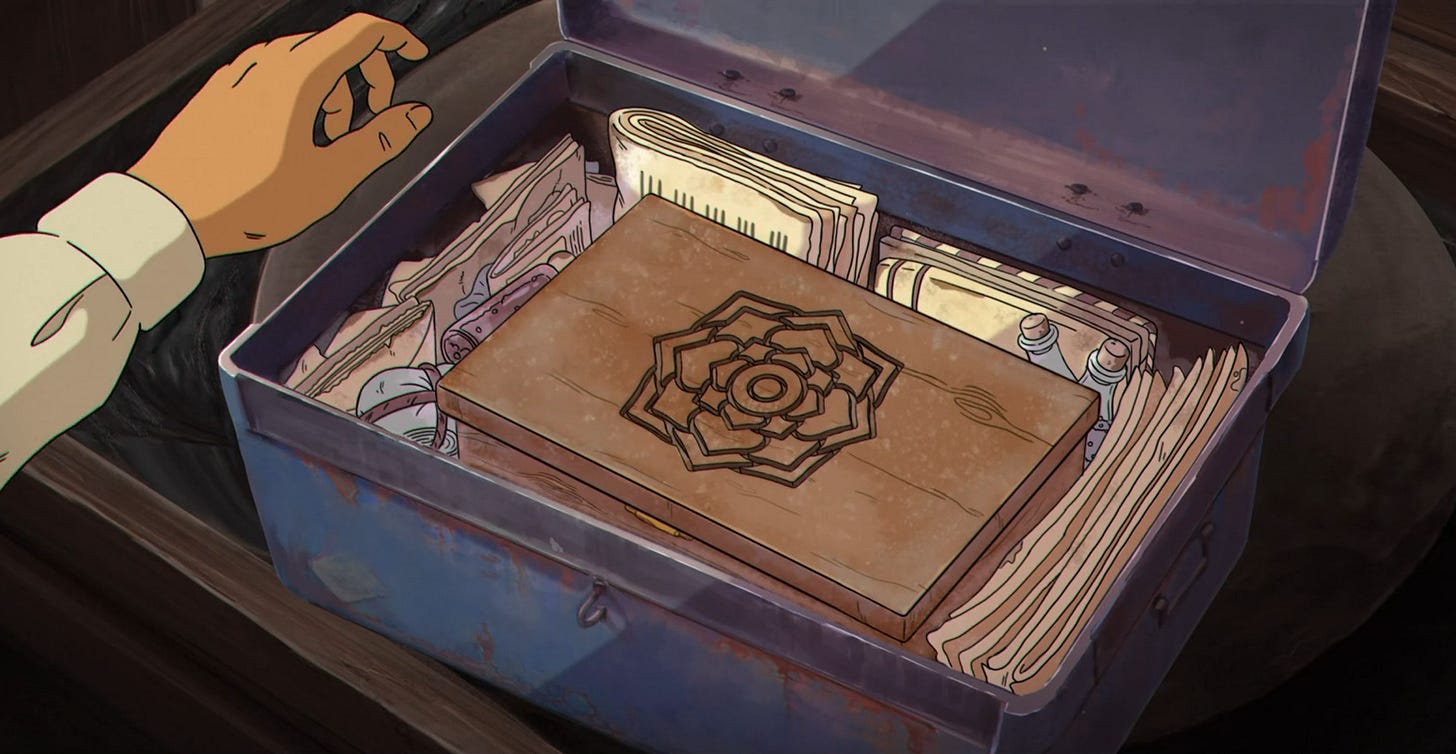

One of the best movies we saw last year was made in Pakistan. Its title is The Glassworker, and it’s the project that could.

It’s a tough, layered story about violence and art. The lead, Vincent, is the son of a glassblower. His father is a pacifist in a country at war — an artist in a country of soldiers. Then Vincent meets Alliz, a musician and a colonel’s daughter. Their parents stand in opposite worlds. The two children learn that they do, too.

After a decade of struggle, The Glassworker debuted at Annecy 2024. Many had counted it out, but the audience loved it. At the festival, writer Claire Knight caught up with three of the film’s top people. We were thrilled to publish the great conversation they had last year.

But The Glassworker’s story isn’t done. In a few days, the film begins its American theatrical run with a screening at the Angelika in New York. Next month, it will open in some 250 theaters across the States, and then in Ireland and the United Kingdom.

It’s exciting news — this film deserves eyes. So, in honor of the release, our teammate John called director Usman Riaz to talk about his filmmaking process, the battle to get his movie made and Studio Ghibli.

The Ghibli point is important. The Glassworker is visibly inspired by its work — “I love those films with all my heart,” Riaz told us. But his movie isn’t a knockoff. It’s not a GenAI clone, or kitsch aimed at commodifying a “Ghibli vibe.” It’s a deep study of Hayao Miyazaki’s and Isao Takahata’s filmmaking and storytelling. Riaz reverse-engineered their ideas and made something fresh, powerful, painful and sometimes brutal, in a way we rarely see.

He and his team bled to do it. “For me, it was this one obsessive goal: I just have to get this movie done, no matter what,” he told us. People have responded to the passion. Cartoon Brew called the film “a lush and evocative viewing experience with a timelier-than-ever message.” It was Pakistan’s submission to the Oscars this year.

We’re hoping more viewers get to see it from here. Our interview (edited for length, clarity and flow) appears below.

John (Animation Obsessive): As I understand it, The Glassworker is your directorial debut. Is this your first experience as a filmmaker?

Usman Riaz: So, this is my first feature film. I directed two live-action shorts — very much in the style of animation, though, as in I storyboarded almost every frame.

The first one was a short called Ruckus that I completed in 2012. I storyboarded the whole thing — hoping I could animate it, realizing that it would be next to impossible. So, I just made it live action. The second one, which I made in 2013, was called The Waves. I also storyboarded that, thinking I could animate it now. But it was still impossible.

Then, with The Glassworker, I wrote the story a few months after finishing that one. And Mariam — my wife, but we were engaged at the time — said that this had to be done in animation. So, I said, “Why not? How hard can it really be?” [laughs] I had no idea what I was signing up for. But it was an incredible experience.

This is my 11th year now on the film [laughs].

John: [laughs]

Usman: I’ve spent one-third of my life with this movie. I’m grateful that it’s done [laughs].

John: The film is really tightly made. It’s much tighter than a lot of debut features, just from a filmmaking perspective. And I wanted to ask about that process of storyboarding. What were some of the movies you looked to for editing and composition? How did you learn how to make a shot, make a scene?

Usman: I’ve been drawing and focusing on composition since I was very small, not thinking I would ever grow up to make animated movies. I watched behind-the-scenes documentaries. I would read about how movies are made. My entire library is filled with making-of books and art books.

Shot composition and editing in film were things I was always fascinated by. And not just [live-action] film, but also cartoons — and, of course, anime. The sense of flow and momentum from shot to shot, and the connection there.

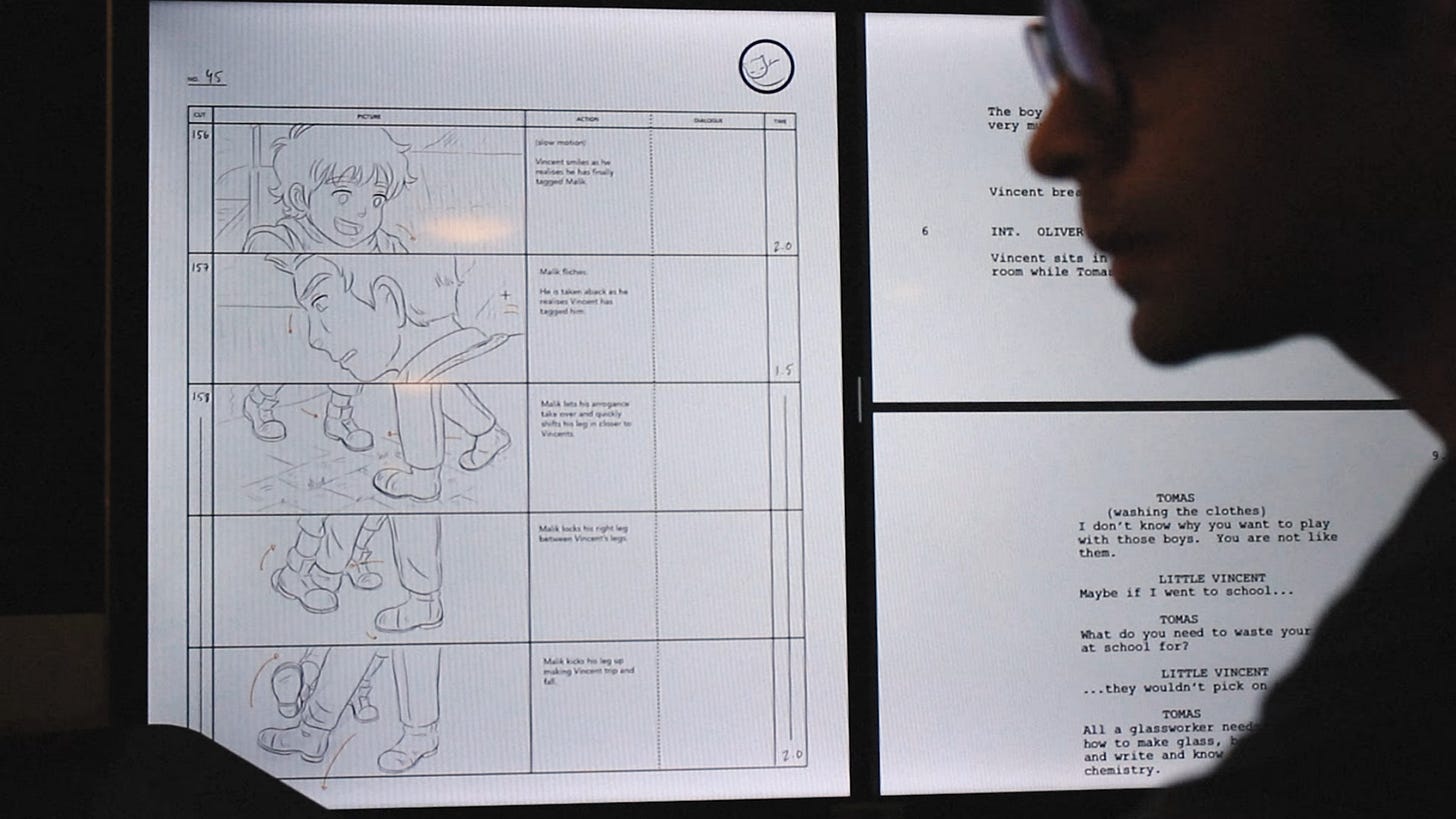

I was always fascinated by the Japanese storyboarding process, because it’s the director’s vision. Sitting down, drawing every frame. Compared to how Western animation is done, where usually it’s a bunch of people drawing the storyboards together, the Japanese process is much more intimate. In particular, of course, I grew up obsessing over the films of Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata.

Isao Takahata didn’t draw his storyboards the way Hayao Miyazaki does. He drew rough compositions, and then people like Osamu Tanabe actually drew the storyboards. But with Miyazaki’s films — there are about five panels on the page, and the way he would… orchestrate his films was something that deeply resonated with me.

Being a composer as well, I could see, “Oh, this is like sheet music, the way it’s all coming together when you just sit and read the storyboards, with the timestamps on the side.” He could see the movie before it was ever edited together. He had it all in his head.

I love working with a camera. Putting in the visual storytelling aspect, and making sure that the shots flow with each other. The basics like the 180-degree rule, of course, but also the visual continuity. That’s why it was important for me to draw every single shot, every single storyboard panel, so that this movie could flow a certain way.

The reason I was doing it was that the team was very inexperienced. And I wanted to cover all my bases, whether they were minor details in the art direction (I would draw the backgrounds in most of the time) or what the characters were doing, how they flowed from shot to shot, moved from one end of the frame to the other.

Planning every single thing was something that allowed the movie to be, like you said, very tight.

John: Bringing up Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli — The Glassworker, obviously, has been compared to their work many times. But the influence I feel isn’t just superficial. A lot of people are influenced by the Ghibli art style, but this movie really captures some of the important core elements of the studio’s work, like creating a sense of reality. What went into understanding and channeling those elements?

Usman: Thank you so much. That was something very important to me.

I understand Studio Ghibli’s style so well, in terms of the way they draw their characters. I never wanted to use that art style for the movie. It really doesn’t [look like Ghibli’s films], but that’s just me obsessing over certain things and saying, “No, the eyes are drawn differently; the nose is drawn differently.” At the end of the day, of course it’s influenced by Ghibli. I wear my heart on my sleeve with that.

But, to me, a Studio Ghibli film — and specifically a Hayao Miyazaki or Isao Takahata film — is not the way it looks. It’s what it makes you feel. It’s the moments in between that make those movies so special. That’s what I wanted to latch on to.

I said, “If I can make somebody feel what a Studio Ghibli movie makes me feel, even if it’s 0.0001%, I’ve done my job correctly.”

I can bring up an example. Sophie [in Howl’s Moving Castle] is sitting near the lake and says, “When we’re old, all you want to do is stare at the scenery.” The water is flowing beneath her feet, and [there are] little things that they’ve done to show the wind blowing. Those minor details — ma; the spaces in between — they’re so perfect. Or when Ashitaka [in Princess Mononoke] sees the Forest Spirit for the first time and there’s just silence. It’s not dramatic at all. And he sees the silhouette in the distance.

Those moments stay with you. I was like, “How can I capture that feeling — that this is a real world these characters inhabit? That it’s not just a movie that’s like a roller coaster, taking you through to the next action sequence?”

John: The way that you take such care with the blow-by-blow process elements, like the glassblowing itself, feels to me like a Miyazaki kind of touch as well.

Usman: Yes. I knew I would have to really understand and study the craft of glassblowing. At the end of the day, I only have a few seconds to showcase all this incredible work that goes into a sculpture. I’ve been obsessed with glassblowing since I was 15 or 16 years old because I saw the Murano glassblowers in Italy.

The opening sequence was very important — where I could show how they heat up the furnace, how all the various things work together. Lampworking is a different craft, where you work in close proximity with the flame, versus making the larger pieces. Putting it into the annealing oven so that it doesn’t crack.

While we were working on the film, I was invited to Peter Layton’s glassblowing studio in London, and they let me come in and film for hours, and speak to the glassblowers. It’s one thing watching documentaries or seeing them on a tour, and another thing talking to them. They said, “It’s a very organic process. Most of the time, the glass doesn’t do what you want it to do. You have to ride the wave of where the piece is taking you.”

That was something I wanted to try to put into the film, and something I could really relate to. Because I can plan The Glassworker and the storyboards all I want, but the journey of making it took me in all these different directions. That wisdom got me through making the movie.

John: Really cool. And the script in this movie is very complex and layered. I’m wondering about the writing process — giving the movie those layers.

Usman: I’m very grateful with the writing process. I got to learn a lot from Moya O’Shea, our wonderful screenplay writer from the UK.

I wrote the story in 2013. I was about 22, 23 years old. On my subsequent trips to Japan, I kept meeting Geoffrey Wexler, who’s the chief of international at Studio Ponoc now. We met in passing at Studio Ghibli in 2015, because he saw me getting a tour — I was crying throughout that tour [laughs]. Then we met again in 2016, and again in 2017. And he said, “You’re one of the few people I’ve seen who’s so serious about making a film. I’ll help you.” And he connected us to Moya O’Shea.

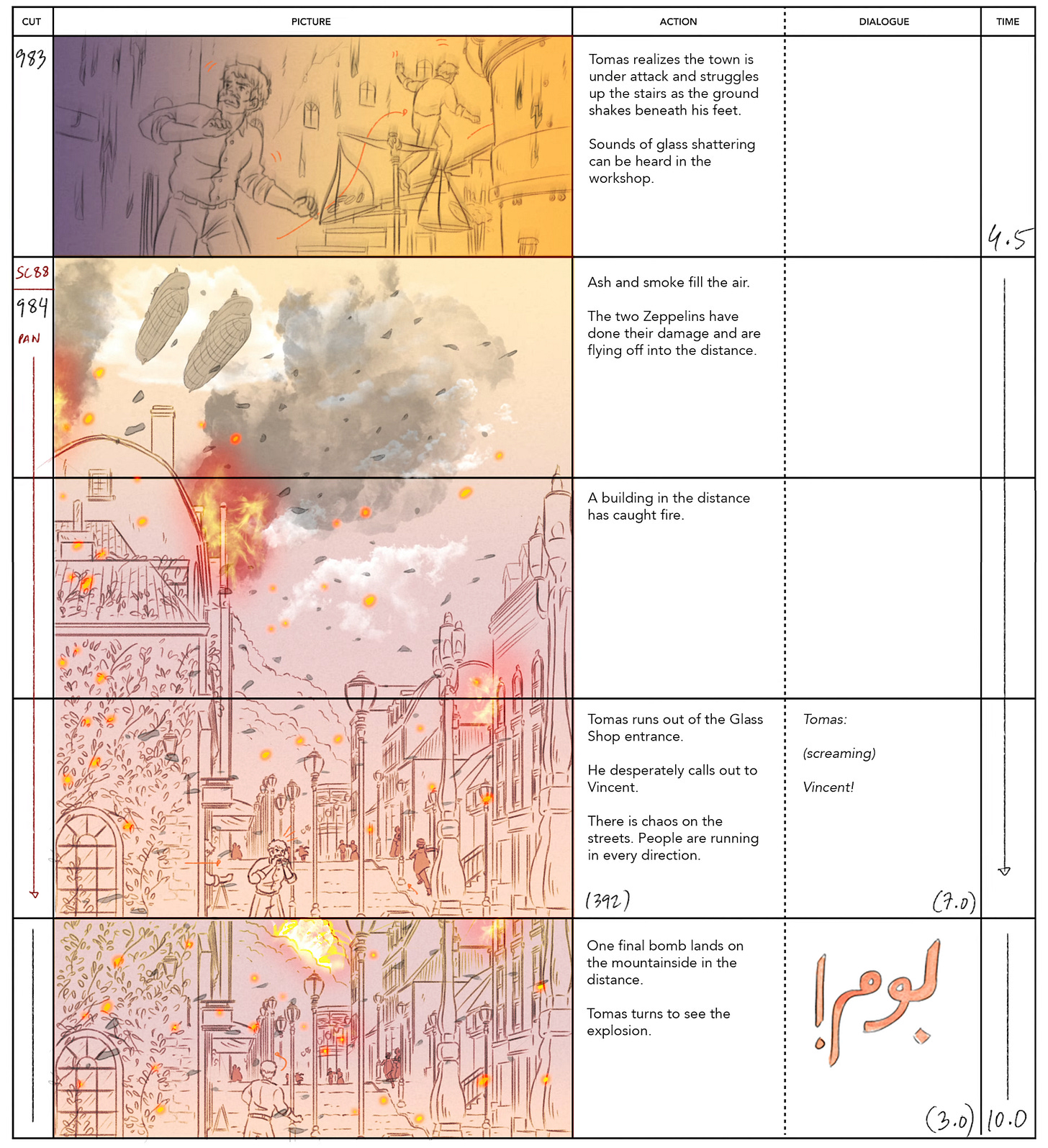

There were a lot of things in the story that I was hesitant to put in. She was looking at all of my drawings and airships and things, and she said, “Let’s not worry about how you’re going to execute all of this.”

That was my biggest concern. I said, “I want to make a feature film. But how on earth are we going to make such an ambitious movie?” With the limited resources I had [in Pakistan], there was no way I could bring all of these things to life. But she said, “Let’s put them into the story, and we’ll figure it out later. We shouldn’t let the screenplay suffer.” I’m grateful she did that.

Throughout the writing process, we kept trying to imbue it with this sense of reality. Geoff and Moya came to Pakistan; they wanted to see the life I had lived that influenced the story I’d written. We kept putting those experiences into the film.

The biggest thing I wanted to do is that there’s no antagonist, that these are real people. Again, something I learned from Miyazaki’s movies, like Princess Mononoke, with Lady Eboshi and San. None of them are inherently evil. They’re just trying to protect the people they’re taking care of, and to live by the rules they’ve laid for themselves. That movie had a big impact on me when I was growing up.

I said, “I want to do something exactly like that, where there’s no mustache-twirling villain. It’s real people and the decisions they make, and the consequences of those decisions.”

Those were the ideas we tried to put into the script. Especially with characters like Colonel Amano and Tomas having opposing worldviews. Neither of them is inherently wrong or right: they’re just trying to live with their philosophy, and suffering because of it. Both characters suffer tremendously because of the decisions they’ve made.

John: There’s a great scene where Vincent and Alliz are in a field, and then a bunch of planes fly overhead. They’ve got two different reactions, and it reveals a lot about their characters and situations in a subtle way. What went into creating that moment?

Usman: I had to show their paths diverging, on the cusp of their teenage years. When they’re children, they don’t really understand the way the world works.

I came up with the sequence of them running through the meadow, playing together with all of this youthful exuberance. And then, ultimately, the industrialization coming from the war makes them realize, “We’re actually two very different people. What is going to happen to us?” It was that feeling I tried to visualize.

There’s no dialogue in that scene. It’s just the music and what the characters are experiencing — taking you through that, and hopefully feeling the divergence that they were feeling.

John: Is there anything that you started to understand about the mechanics of good filmmaking during this whole process of making The Glassworker?

Usman: You can prepare as much as you want, and understand what it’s like to make a movie. But you will never be prepared for when you’re actually put into the situation.

Making animation and drawing and painting as a hobby is very different from working with deadlines. Mind you, self-imposed deadlines — because there was no pressure to make this movie apart from the pressure that I and we put on ourselves. I’m very grateful that I got to work with a remarkable group of people.

I think the one thing I learned throughout this journey — because, for me, it was very long — is that you have to be tremendously focused and committed to the decisions you’ve made. Maintaining that same level of enthusiasm every single day is very, very difficult, [but it’s] what keeps the others motivated.

Another thing I’ve learned is, I never want to make a movie this way again [laughs]. Spending a decade to make a movie is insanity. Like, there must be a better and quicker way to do it. I’m trying to find that now, as I work on the next project.

But maintaining your love for film and animation and storytelling. Keeping that childlike wonder inside — that was something I tried desperately to hold on to. That was the biggest lesson I took away. You have to keep that child inside nurtured, because that is what gives you these, I don’t know, otherworldly abilities to get this done. There’s no other way I can describe it.

I look back and I sometimes wonder, “How did I get through that?” Of course, one of the reasons is God, but the other reason is just maintaining that passion and enthusiasm to see you through to the end.

John: The Glassworker opens in the United States, in New York, this month. And it’s coming to several hundred theaters in September. What are you hoping comes of it? What does it mean to you for this to reach the world in this big way?

Usman: When you’re making a movie, you know what you’re doing, and you’re just problem-solving every day to reach that goal. This is the first time where I have no idea what’s going to happen. And I’m cautiously optimistic slash absolutely terrified [laughs].

Everyone, especially independent filmmakers, can say that we don’t make movies for commercial appeal; we make them for ourselves. But people have to watch the movie and enjoy it as well. It’s a communal experience — you make movies to share them.

If you’ve made a movie just for yourself and you watch it at home on your projector, that’s wonderful. But the true experience is sharing it with an audience and having them enjoy it. Just like the way that a kid from Karachi was so moved by Hayao Miyazaki’s movies that he wanted to make one himself.

I don’t know what is going to happen. I just hope that people enjoy it, and I get to keep doing this.

John: The Glassworker originally premiered last year at Annecy. What’s changed for you in the time since it was finished?

Usman: You know, it’s funny. I thought finishing the movie would somehow unlock another aspect of my personality, and [I would] realize that I have a lot of the answers. I thought I would have everything figured out as I embarked on making the next one.

But I’ve come to realize that you still don’t hold all the answers. The only thing I can say is, “Oh, I’ve done it before; I can do it again.” I still have to figure everything out, differently. The only thing that’s changed is the confidence — the biggest thing is that the fear is gone. Everything else, you just keep rediscovering.

It’s a never-ending journey. As soon as you climb a mountain, you realize, “Oh, there’s an even bigger mountain to climb.” I’m trying to put my thoughts the best I can without sounding super pretentious [laughs].

John: No — I love it, I love it. Has there been a highlight that’s stood out from releasing The Glassworker so far, and from people finally getting to see it after all these years?

Usman: I think one of the best moments was… I was sitting in Madrid, and we were doing the film finalization, and getting the sound work done with a wonderful company called Milciclos. It was just me and the [second] producer, Manuel Cristóbal — the first producer is my cousin Khizer Riaz.1

Working with the extremely professional team, we’d wrapped up the entire film’s sound in 10 or 11 days, which was amazing to me. The dinner that I had with Manuel in Madrid after the film was done, where nobody knew what we had accomplished except the two of us, was a very special moment. He said, “Usman, it’s done.” And I said, “Yes. I don’t believe it, but it is.”

John: I guess I’ll wrap up by asking: do you have any advice for people, especially people who may lack resources or infrastructure in whatever country they’re working in, who want to do something like what you’ve accomplished here?

Usman: You know, there’s a complete lack of animation and film infrastructure in Pakistan. And I was able to pull this off primarily because of the support from my family, and my parents in particular, who have never stopped me from doing anything throughout my life. Even if they didn’t understand what I was doing. And I’m very grateful for the support of Mariam, my wife, who’s the art director and associate producer.

Even though I’ve been absolutely unbearable throughout the course of making this movie, because of how obsessive and worried I was, everyone still supported me. Like I said, I got to work with a remarkable group of people that somehow came together.

The one thing I can say to others who want to do something similar is, don’t let go of your obsession and passion. I was told at every single stage, “You’re never going to do it because no one’s done it before. And there’s a reason no one’s done it before, because it’s impossible.”

I said, “We’ll start off with five minutes.” [People said,] “How are you gonna make five minutes? It’s impossible.” Then I was able to put a team together to make a few minutes. They said, “Well, you need a lot more money. No one’s going to give you money.”

I did the Kickstarter to raise that money. Then people were telling me, “Even though you’ve done all of this, you’ll never be able to write the full script or raise the money to make a feature film.” While hearing that, I still was able to do it. Then they said, “You’ll never finish the movie, because who’s going to be obsessed with this project for so long?” [laughs]

Kept my head down. Finished the movie. Then people said, “You’re never going to get into festivals. There are so many amazing animated movies. Why would yours get selected?” Then it was selected for festivals [laughs]. I can go on and on.

I just ignored all that. Did it hurt? Of course it did. Every time it would hurt, because I’m not bothering anyone. I’m not telling them not to pursue their dreams. I mean, the world is so strange that way. I would say the most important thing is, skepticism and being overly critical are not signs of intelligence. It’s being hopeful in an overly cynical world.

And that’s not naivety. You have to keep moving forward — and everyone will tell you it’s impossible. But, if you believe in something, keep going. Everyone’s journey’s going to be different. Mine doesn’t look like any of the journeys I’ve read about and obsessed over. But that’s your path. Just keep walking along it. Don’t give up.

2 – Newsbits

A quick one from Australia: Felix Colgrave released a tiny, mesmerizing piece of animation called Body Surfin’ on YouTube.

Don’t miss Pollo Punch, either. It’s a really strong short from America — funny, well-told and animated with a lot of creativity.

Speaking of The Glassworker: a Japanese crowdfunding campaign aims to finance a local dub. Behind the project is Elles Films, the scrappy distributor that brought The Stolen Princess from Ukraine to Japan.

Also in Japan, the 21st entry in the Ghibli Textbook series is out. This one is about The Boy and the Heron. (The studio animated a new commercial, too.)

In China, Nobody is doing great at the box office. It’s earned more than $79 million already, according to Maoyan. This is a big summer for 2D animation in the country: another film, The Legend of Hei 2, just broke the $55 million mark.

The Straw Hat Pirates’ flag from One Piece has taken on new meaning in Indonesia, where people are displaying it to protest against the government.

A new festival, ToonDook, starts next month in Kyrgyzstan. It’s reportedly the country’s first dedicated to animation.

In Nigeria, a short called Sopo attracted celebrities with its premiere screening — Burna Boy among them. See the trailer here.

The German government doubled its funding for movies and TV, and animation stands to benefit. One official argued, “We need more blockbusters and series hits made in Germany.”

Last of all: we explored the making of The Metamorphosis of Mr. Samsa, a classic that Caroline Leaf animated in sand.

Until next time!

Manuel Cristóbal, one of the key producers in European animation, played a big role in making The Glassworker happen. Riaz’s completed storyboards called for a “one hour and 56 minute movie,” as he told us. Cristóbal thought that it could be condensed, so Riaz worked with editor José Manuel Jiménez to revise things.

That included collapsing the film into one perspective — Vincent’s. Like Riaz said:

Initially, the film was from Vincent’s perspective and Alliz’s perspective. Throughout the edit, we decided, “It’s called The Glassworker. Let’s keep the point of view Vincent’s completely. All the things that happened with Alliz should be his memory of what transpired, and what she has written in the letter.” That’s why the letter was very important — because we get her perspective through it. I think that really benefited the POV of the film. You’re experiencing everything with him.

I grew up obsessing over Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy as well, and I loved the books. My parents were huge fans, so they made me read The Lord of the Rings. And that book is multiple characters’ perspectives. What they did so greatly for the movie was, they made it primarily from Frodo’s perspective. That’s something that I kind of tapped into [while] editing it down.

Usman. You are right. Everyone's path is different. Eventually, we will all get to our destination if we work hard enough. Just ask a filmmaker named Denver Jackson. He proved that making an animated film on your own is not impossible. I will prove it as well. Both of you represent a new generation of filmmakers that I have come to admire for different reasons. Congrats on your film my friend and any success that comes your way. It is much deserved.

This movie will find its audience. There are a lot of accusations about the film being some A.I. Studio Ghibli app ripoff. It's a shame because a lot of care and artistry went into the production. Mano Animation Studios has a great doc that details the painstaking process of putting this animated film together. I suggest people check it out. It is highly educational for any filmmaker or anyone curious about the medium of filmmaking. Here is the link to the doc. https://youtu.be/rxAOUJt1PaU?si=WRpf1B203cfunWmR