Revisiting One of the Greatest Stop-Motion Films

Plus: news.

Welcome! Thanks for joining us today. It’s another Sunday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and here’s our lineup:

1) About The Hand.

2) Animation newsbits.

With that, let’s go!

1 – A very famous man

There’s a birthday coming up. In a few months, The Hand will turn 60. It remains a stop-motion masterpiece — as relevant as it’s ever been.

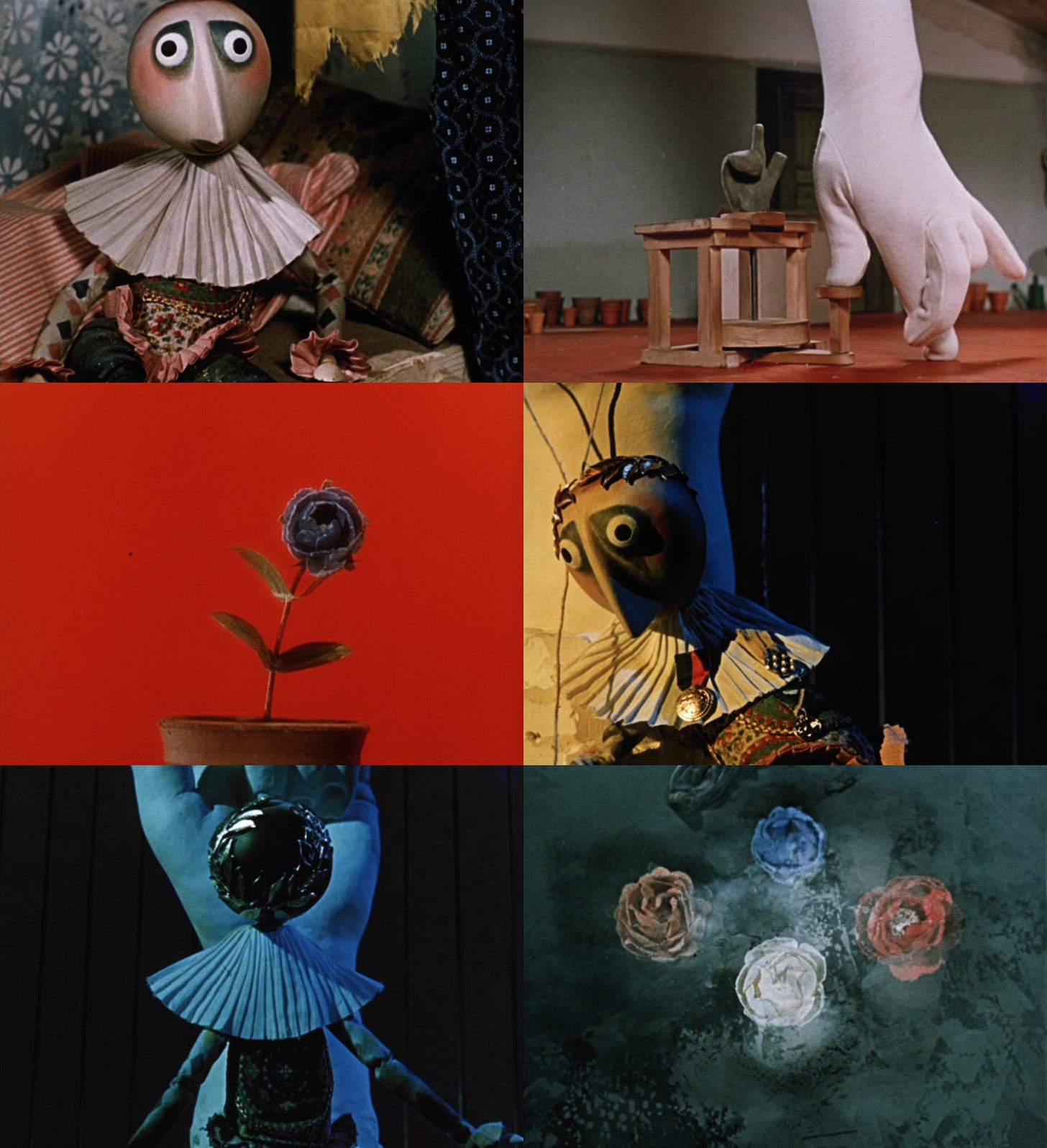

To the extent that people know the work of Jiří Trnka, it’s often this one. Made in communist Czechoslovakia, The Hand is a protest against power. It’s an 18-minute escalation, set mostly on one stage, with no dialogue. There are just two characters: a humble potter and a conniving, brutal hand, which nudges and flatters and bribes and threatens our hero to sculpt a statue. A statue of itself.

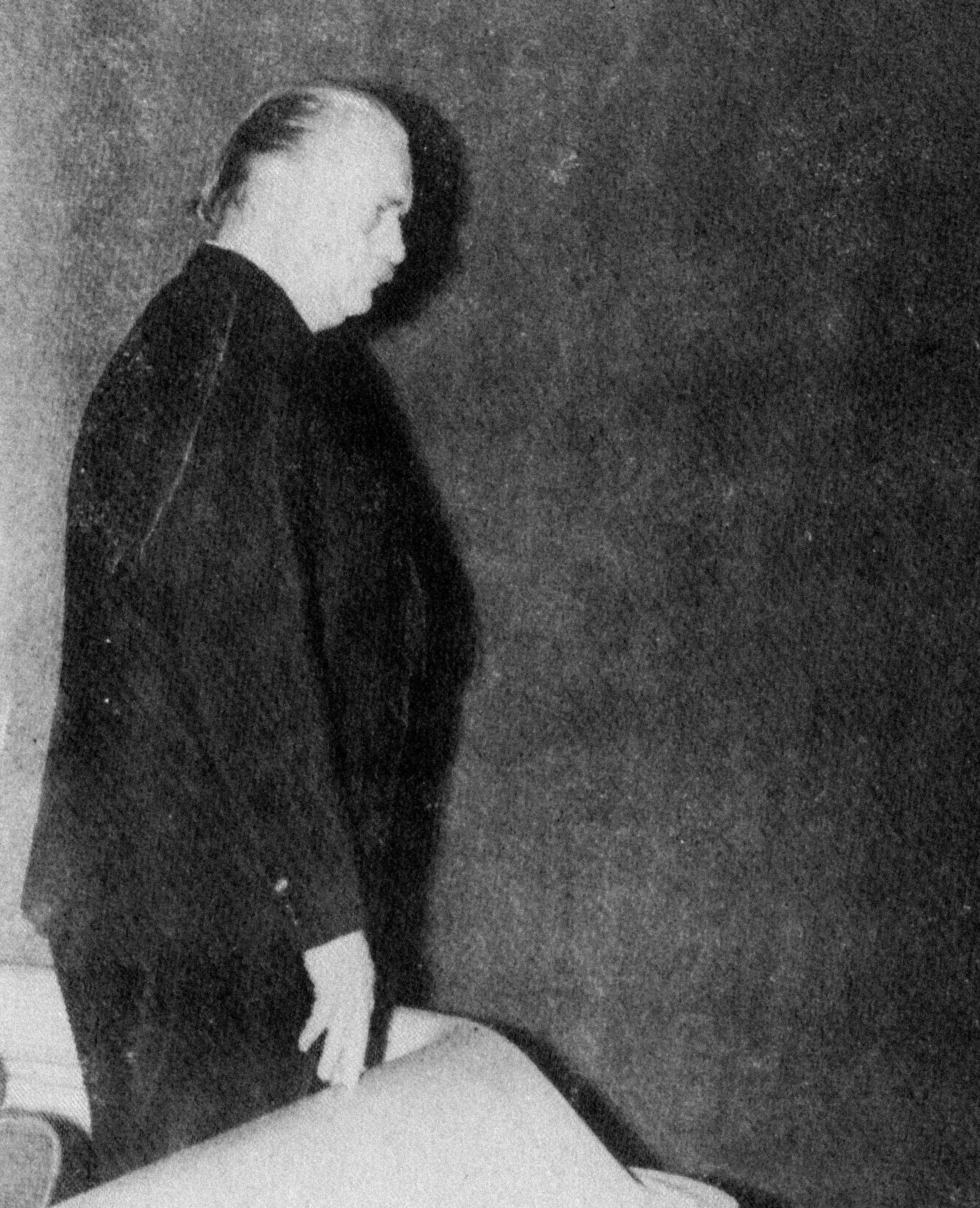

This was both allegory and autobiography. At the time, Trnka may have been the best-known Czech in the world. He was “a very famous man,” as he once told an American animator. Trnka had state honors, fancy cars, drums of caviar, a villa for his family. By 1963, there was talk that he was among the wealthiest people in Czechoslovakia.1

It somehow didn’t go to his head: he stayed a driven, sensitive artist with good intentions. And he made beautiful things with the creative leeway he had. Trnka was a director and illustrator (responsible for films like A Midsummer Night’s Dream) who grew into a national icon. A symbol of Czechoslovakia.

Later, though, that American animator understood the double meaning of Trnka’s words. He was a very famous man — that is, a valuable tool. The state was using him, and its officials tried to keep him under their control. It was good optics to have a celebrated artist in the country, so long as he didn’t cause too much trouble.

“As an artist, Trnka needed absolute freedom, and to a great extent, he had it,” explained one writer. “Yet he had also unwittingly become a part of the communist machinery, and he knew this full well.”2

The result was a spiral of disillusionment that gave us The Hand, Trnka’s last major film. With it, he made a complex statement — often mistaken for a simple one.

During the final decade of his life, in his frustrated years, Trnka kept bringing up Oppenheimer.

He mentioned the name in reference to his film The Cybernetic Grandma (1962), about a dystopia caused by technology. “I realized the urgency of the idea again when I read Oppenheimer,” Trnka said.3

The man was still on Trnka’s mind when he made The Hand. In his words:

... the hand is not admiral or papal or political, but simply the hand that has the power of power, as well as of convictions, and it means well by the puppet.

It is omnipresent, it has always been, regardless of nationality, all over the world, and it forces each individual to do what they do not wish to do. Something sweeps through history, perhaps an institution, convinced that its truth is the universal truth, demanding attention and requiring everyone to agree with it. … The victim could be anyone from antiquity, or Galileo Galilei, at another time Oppenheimer.4

For Trnka, Oppenheimer may have looked like a fellow traveler. He was a man empowered by the state for its own ends — sometimes decorated, sometimes scorned, but always exploited. By making The Hand, Trnka was revealing this situation to the world, and trying to fight back in the way that he could.

He didn’t conceal his message — which was a risk. Czechoslovakia was a dictatorship, and he knew people who’d faced repercussions for lesser slights than The Hand.5

While Trnka always made points in his films, they weren’t like this. He had a reputation for visually intricate, even Baroque projects, but The Hand is stripped down to a spare minimalism. It’s a few key elements in support of a statement. In many ways, it doesn’t feel like his work. It’s eerie: it qualifies almost as a horror-tragedy.

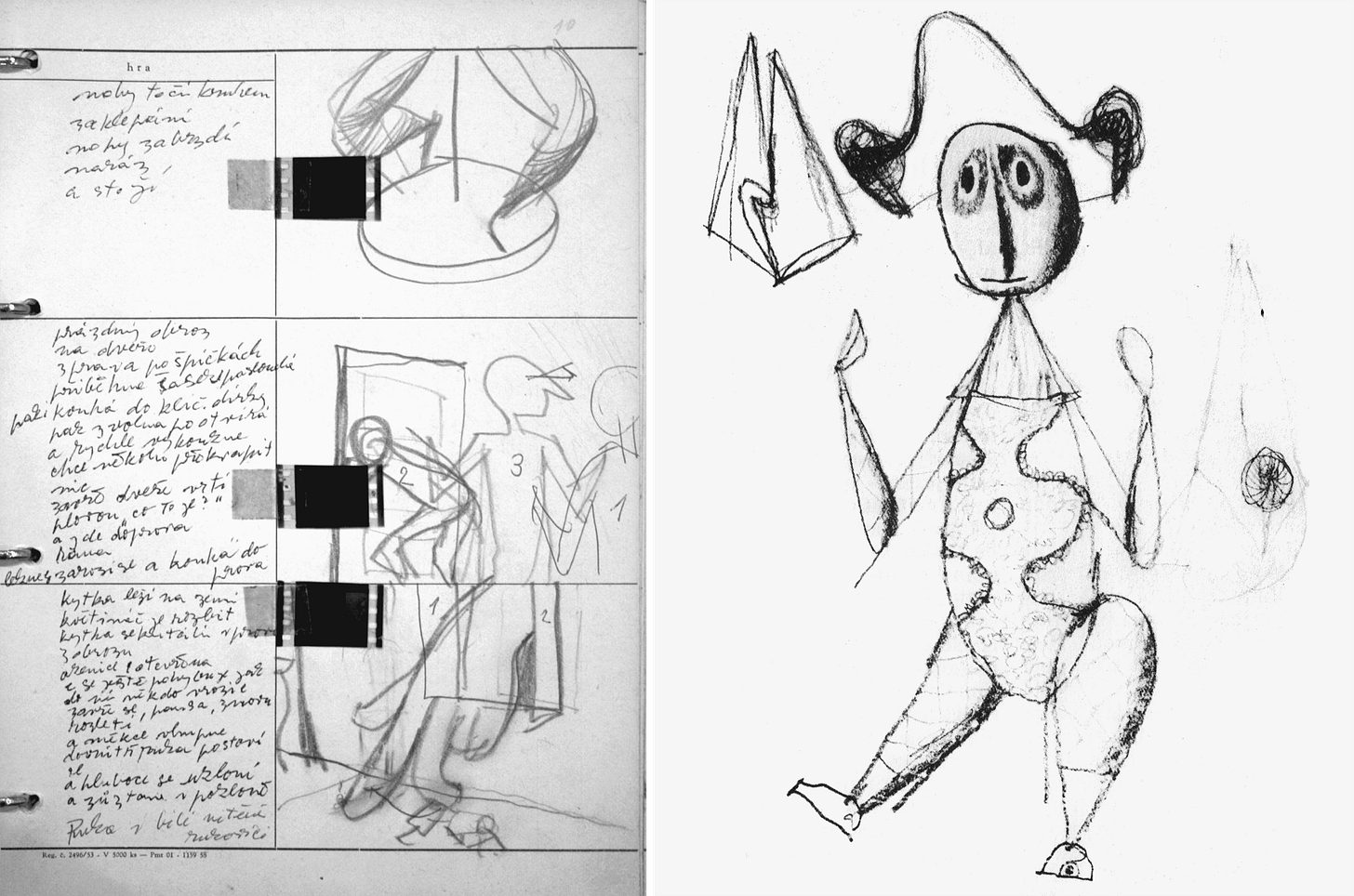

Not that Trnka pitched it as a horror-tragedy. In the screenplay, The Hand’s title is joined by the words maňásková komedie aneb Duranty naruby — “a puppet comedy, or Duranty upside down.”6

Louis Duranty was a writer in France during the 1800s. Over a hundred years before this film, he’d penned a marionette play called The Grand Hand, which Trnka read in translation. Duranty’s version stars an unruly, destructive character and a hand that keeps him in line. Like Trnka said in 1965, that original character:

... is unrestrained, wild and disorderly, and the hand represents law and justified discipline. By contrast, the puppet in the film The Hand does not need to be reined in, because there is no reason.7

In other words, Trnka flipped Duranty’s story on its head. The artist at the center becomes an innocent person, badgered and abused by power. And Trnka insisted that this artist’s job was only “coincidental” — in fact, the lead character represents “a Jester of any profession or conviction.”

He has a face to match. “It is not a specific, characterizing face,” Trnka said, “but a mask under which any face may hide, a person of uncertain profession and age, and ultimately even era and nationality.”

By this point in his career, Trnka was almost unrivaled as a director of animation. He threw the weight of his talents behind The Hand. For all its severity, it’s a beautiful film, full of his master-level design and composition.

It stuns on the technical side, too. Two animators, Bohuslav Srámek and Jan Adam, worked under Trnka to deliver animation so polished that you nearly take it for granted.

See the hand character, for example. It moves through “pixilation” — a live actor filmed in stop motion. The Hand was shot “on ones” (24 images per second), which can make pixilation look jittery or scattered, but this character is tightly choreographed and controlled throughout. Trnka worked with Ladislav Fialka, a renowned mime, to design its motion.8

Then there’s the lead puppet. At an exhibition of The Hand’s production materials in 2012, the animator Vlasta Pospíšilová said:

... this little man here was animated by Srámek. When I watch this film, The Hand, I’m moved to tears by the character, poor little guy, who despite his rebelliousness fails to achieve anything, and in the end is overwhelmed by those in power.

You can credit part of the performance to the animators and part of it to Trnka himself. Pospíšilová, who worked for Trnka on other films, remembered that he “was good at telling the animator what to do in such a clear way […] He knew how to describe, to explain in detail, the character to be animated.”9

One other key aspect of The Hand was Trnka’s collaboration with his composer, Václav Trojan. They’d been together since the ‘40s, but the style was different now: starker, colder, harsher. Historian Marco Bellano has noted the soundtrack’s “artificial timbres” and “single sounds, ostinatos or dissonant passages.”10

As Trojan himself said:

I would like to stress again that Trnka always wanted to do something different; he wanted to try things, to experiment. His last experiment was The Hand, where, as far as the audio was concerned, there were in fact many more sounds than actual music.11

When The Hand hit the international film circuit in the mid-1960s, it was a sensation. It swept festivals — picking up a jury prize at Annecy and the top animation award at Oberhausen, among others. But a question mark has always hovered over the film.

“Audiences wondered how Trnka got The Hand’s storyline past the authorities since filmmaking was state-sponsored in Czechoslovakia,” explained historian Howard Beckerman. “It is said that he told them that it was a tale about capitalism. Well, why not? Trnka’s art is universal; his oppressive Hand obviously represents any authoritarian enterprise, be it government or corporation.”12

As Trnka’s reference to Oppenheimer makes clear, his target really was bigger than his bosses, and he was disillusioned with more than Czech communism. Speaking about The Hand’s meaning in 1966, he said, “Fellini creates a great personal message in 8½, but some hack politician will claim that his own viewpoint is the only objective one.”

Around the same time, Trnka attacked the Cold War propaganda of both the United States and his home country. Newsday reported:

Trnka is not a happy man. He explained one source of his despair: “Truth is so hard to obtain today. The western press says that everything is wrong in communist societies, and when our press describes the West it usually talks of race riots, strikes and the revival of fascism.”

Then he held up a four-page communist paper and said: “Look at this paper. It has only four pages and half of them don’t make any sense. Why should teenagers believe when adults don’t tell the truth?”13

As if to prove Trnka’s point, the Boston Globe selectively reprinted his remark about that communist paper, painting Czechoslovakia as a villain and hiding the broader argument he was making.

Which became a running theme with The Hand. During the Cold War, the most political, anti-state art from Eastern Europe got the most buzz abroad. Beckerman wrote that The Hand became “a popular film at colleges and universities, accepted as a commentary on life behind the Iron Curtain.” Never mind that Trnka identifies the hand of the Statue of Liberty, no less than Napoleon’s hand, with the villain of the film.

Meanwhile, in Czechoslovakia, The Hand received several glowing reviews from the papers when it premiered.14 This was the era of Czech New Wave cinema — rebellious live-action movies were sweeping the country. The Hand’s boldness rankled some, but Trnka brushed aside the criticism. “Official taste is bad taste,” he said in 1966.

The state never managed to pacify Trnka. A few years after this film, he co-signed the infamous “Two Thousand Words” manifesto, a direct attack on those in power.15 Even so, The Hand’s dark message is about Czechoslovakia no less than it’s about America. And the country’s officials would prove Trnka’s point in their own way.

There are disagreements about when, exactly, Czechoslovakia started to suppress The Hand. It did hit theaters initially, and Trnka remained active in Czech art until his premature death from health problems in 1969 — building a gorgeous section of Expo 67, teaching, painting and sculpting.16

But what’s clear is that the film was banned outright by the 1970s. Historians Jan Poš and Edgar Dutka point to the year 1970 exactly — just after Trnka passed away, and during the so-called “normalization” crackdown. Dutka wrote:

When Jiří Trnka died in [December] 1969 (at only 57 years of age), he had a State funeral with honors. Only four months later, The Hand was banned; all copies were confiscated by the secret police, put in a safe and the film was forbidden for screening for the next twenty years.

The irony of Trnka’s state funeral was obvious — it was almost a mirror image of The Hand’s ending. Reportedly, the Ministry of Culture and the Czechoslovak Film Institute sent delegations that included Kamil Pixa, a bureaucrat who’d played a major role in the secret police. The Minister of National Defense offered his condolences.

“Trnka’s versatile contribution to the creation of puppet and cartoon films,” wrote the Minister of Culture, “will remain permanently inscribed in the history of our and world cinema.”17

It’s often said that The Hand predicted the future — in the scene where we realize that the artist is trapped within a closed system. The little puppet never stood a chance. Nevertheless, Trnka’s own funeral took place more than 50 years ago, and it’s worth refreshing our view of The Hand, and of Trnka’s legacy, in light of the passage of time.

The story is familiar: Czechoslovakia is gone, but The Hand is still here. And it never truly left.

Edgar Dutka remembered that, even in Prague, the Krátký Film studios still had a reel of The Hand during the 1970s. “We watched that film, a copy had been saved,” he said in 2012, “it had escaped censorship, and we sometimes secretly watched it in the screening room. It really is a masterpiece and impressed us greatly.” Jiří Barta (The Pied Piper) cited The Hand as an influence on his decision to animate.18

It kept circulating outside Czechoslovakia, too. It reached Europe, Japan, the United States and beyond. Yuri Norstein of the USSR once named it his “favorite animated film.”

By the 1990s, The Hand was canonical. By the 2000s, it was a given. It remains widely taught around the globe. Rebecca Sugar has called it an inspiration. Every greatest-animation list that matters features this film. And its agitation against power still speaks to today’s world.

The Hand’s complexities and personal side aren’t always clear to modern viewers — and the film has unfairly paved over the reputation of Trnka’s other work, which it barely resembles. But it’s an indisputable classic, with an enormous impact. Trnka’s protagonist was locked in a closed system, but Trnka’s protest wasn’t. It broke out.

This is a revised and expanded reprint of an article that first ran in our newsletter on January 26, 2023. It was exclusive to paying subscribers then — now, it’s free to everyone.

2 – Newsbits

In America, the great indie animator Jonni Peppers released her latest (mostly) solo feature: Take Off the Blindfold Adjust Your Eyes Look in the Mirror See the Face of Your Mother. Check out the trailer here and the complete film via her Patreon page. We’re mesmerized by this one and will write more soon.

This week saw the 10th anniversary of Studio Ponoc in Japan — the studio behind wonderful stuff like The Imaginary.

Indonesia is still all-in for Jumbo. The film passed 5 million admissions and beat Frozen II’s record for animation in the country. Now, it’s one of Indonesia’s top-10 movies, and Southeast Asia’s most successful animated film.

As the anime industry struggles with overproduction, Japan’s Toho has revealed a bold plan: doubling its annual anime series productions by 2032.

Annecy 2025’s WIP showcase was revealed. On the list: Women Wearing Shoulder Pads by Cinema Fantasma (Mexico) and The Mourning Children by Contrail (Japan). If you haven’t seen the teaser for that second one, don’t miss it.

In Russia, Soyuzmultfilm has returned a number of cartoons from the 1940s to theaters, in restored quality. Among them is the very influential Little Gray Neck (1948).

In Japan, there’s a feature called Sunny on the way. Attached are director Michael Arias (Tekkonkinkreet) and the stop-motion team at Dwarf (Pokémon Concierge).

China’s Nezha 2 will get an English dub and new international releases. The film has “already become the highest-grossing Chinese film in Europe in 20 years,” as its European distributor told Variety.

Meanwhile, inside China, Poison Eye examined the role of American imports at the box office. They don’t match the returns of Chinese films, but they’re precious to the country’s theaters. The trade war may mean trouble at home.

Last of all: we wrote about the art of pacing — at Jeffrey Katzenberg’s Disney and during Hayao Miyazaki’s early career.

Until next time!

Kihachiro Kawamoto mentioned this on page 39 of Czech Letters & Czech Diary (チェコ手紙&チェコ日記). That American animator who spoke to Trnka was Gene Deitch, and he published his memories of the encounter here — a source used several times.

From Jiří Brdečka: Life, Animation, Magic (2016) by Tereza Brdečková.

See Kulturní tvorba (April 30, 1963) and Film a doba (January 1979).

From Film a doba (August 1965), used multiple times today.

The theme of art-against-power wasn’t unknown to Czech puppet animation. In 1959, Trnka’s animator and protégé Břetislav Pojar released The Lion and the Song, a film about a performer who’s killed by a lion. The lion dies as a result; the performer’s art survives. It angered Czechoslovakia’s officials, and Pojar’s career took a hit. See this interview.

For details on the Duranty influence, and many more about The Hand, see this thesis by Lucie Kohoutová. An important source.

Trnka said this in an interview with Kino (July 15, 1965), another important source.

Many sources claim that the hand is Fialka’s own, but it seems to have belonged to Srámek and Adam, who took on different scenes while wearing gloves. Kohoutová learned this from Trnka’s daughter-in-law, Helena Trnková, who worked on The Hand.

Interestingly, Trnka saw the lead puppet as an understated role, in terms of movement. “The figure in The Hand says more by his appearance than by his performance,” Trnka told Image et son (June–July 1969). “It has often been claimed that this figure is well animated. This is quite possible, but it is enough to compare him, for example, to Neklan from Old Czech Legends to see how conventional the animation is. What ‘acts’ is found in the character himself, not in his animation.”

From Bellano’s book Václav Trojan: Music Composition in Czech Animated Films.

From a 1970 interview with Trojan (“O Jiřím Trnkovi s Václavem Trojanem a Jiřím Brdečkou”), as reprinted in the book Animation and Time.

From Krátký Film: The Art of Czechoslovak Animation, also the source for Jan Poš’s write-up.

From the Suffolk edition of Newsday (May 12, 1966). The Boston Globe article was printed on November 12, 1967. Trnka’s lines about official taste and Fellini come from Newsweek (March 28, 1966).

Quotes presented in this thesis. Jaroslav Boček raved about the film in Kulturní tvorba (see his review here), and similar praise came from Kino.

See Literární listy (June 27, 1968) for the manifesto, signed by a number of prominent people in Czechoslovakia — Jan Svankmajer among them.

For details about Trnka’s turn toward sculpting and painting late in life, see Image et son (June–July 1969). In that interview, he said that his interest had shifted toward capturing movement in a single image, rather than on film.

See Rudé Právo (January 7, 1970 and January 9, 1970).

Also from Animation and Time (“Jiří Bárta: Čekání na golema”).

A beautiful tribute and reflection. I hope in the future you are able to give similar length and depth to The Cybernetic Grandma / Kybernetická babička! ^^

I haven't watched The Hand since animation school. Thanks for helping this masterpiece bubble back up in my brain!