Welcome back to the Animation Obsessive newsletter! Thanks for joining us. Here’s the agenda for this week:

One — Satoshi Kon, storyboard virtuoso.

Two — animation news from all around the globe.

Three — a quick look back at the first foreign-made cartoon to win an Oscar.

Four — the last word.

If you’re new around here, don’t hesitate to sign up — it’s fast and free. Catch our newsletter in your inbox every week:

Now, let’s go!

1. The sketches of a perfectionist

This week, the Substack writer Mark Slutsky published an interview with Satoshi Kon. It lit up the internet — and for good reason. Before his untimely death in 2010, Kon built a reputation as one of Japan’s best anime directors. Slutsky’s interview dates to 2007, the year that Kon’s Paprika hit America. It’s rich with insights, and it’s a clear example of Kon’s willingness to explain the thought behind his films.

At one point, though, Kon addresses the storyboarding process. “It was like a nightmare,” he says. To craft Paprika’s surreal imagery, he had to make “the most detailed and the biggest one in all [his] works.” For Kon, that says something.

Anime directors have a history of storyboarding their films by themselves. It isn’t universal, but Hayao Miyazaki (to take one example) has done it many times. The recent Children of the Sea got the same treatment. Still, Kon always brought an uncommonly intense perfectionism to storyboarding. That only grew as he aged.

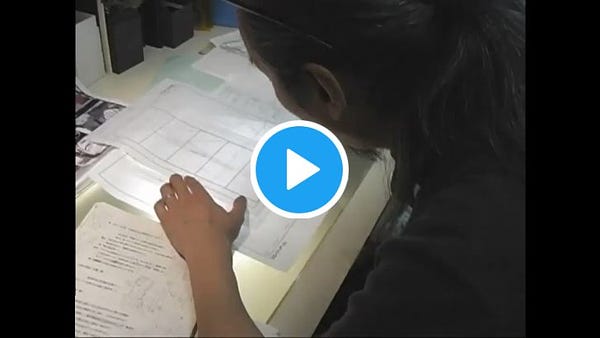

For Paprika, the storyboards were a bitter struggle that lasted a year and a half. Seeing them is like seeing the film in miniature, at a level of detail comparable to what appears on camera. In documentary footage from the time, you can watch Kon drawing them — figuring out the film as he goes and chasing leads as they arise. His clarity of imagination is stunning:

But this obsessive detail, this desire to pin down each individual beat in the storyboards, was always part of Kon’s work. It was how he made films. When he premiered his first feature, Perfect Blue, an interviewer asked Kon if “some of the scenes turn[ed] out differently than what you had visualized or imagined.” The reply was telling:

No, not at all. The final images are what I visualized them to be. I started out as a painter, so I think in terms of visualized drawings from the beginning.

It wasn’t just his background in painting, either. Before he entered anime, Kon worked with Katsuhiro Otomo as an art assistant on Akira — maybe the most relentlessly hyperdetailed manga of the ‘80s. Otomo carried that sensibility into the anime version, which he storyboarded by himself. As his profile in anime rose, he pulled Kon up with him.

“Thanks to Mr. Otomo’s help,” Kon later said, “I was able to begin working in the anime industry.”

Kon started out in anime as a layout artist for the Otomo-penned Roujin Z. Even back then, Kon captured scenes in a crisp, lucid way. (See a few of his layouts for the film via Catsuka.) Otomo’s influence on Kon was undeniable, and he continued to open doors for him. One of Kon’s early breaks was writing the screenplay for Magnetic Rose, part of Otomo’s Memories anthology. Then Otomo got Kon on Perfect Blue.

In terms of detail, Kon’s storyboards for Perfect Blue rival Otomo’s storyboards for Akira. But Kon’s eye is stronger. He already has a master’s grasp of exactly where to point the camera, exactly how to pace each scene. Going over his storyboards, you realize that you’re watching Perfect Blue in slow motion — almost every shot is in place, sketched by Kon himself.

Still, Kon ultimately wasn’t happy with the film. The images might have been there, but it didn’t come together like he’d hoped. “When I watch it again,” he said in 2008, “I feel inspired to keep improving my current work as if my life depended on the outcome.”

As a storyboarder, that’s exactly what he did. He upped his game in Millennium Actress — you could publish its storyboards unedited as manga panels. (See a few here.) Then he reached an entirely new plane with Tokyo Godfathers in 2003. Its storyboards double as immaculate layouts, with character drawings almost like key frames.

Kon always credited his teams with how his films turned out. Yet, especially by the time of Godfathers, he was defining these projects to a startling degree. You see so much of the inventiveness, so many of the iconic scenes, right there in black and white. It’s common to overcredit directors — but these were Kon’s films.

For his sole TV series, Paranoia Agent (2004), Kon didn’t storyboard every episode. It would’ve been impossible. On the ones he did board, though, his work looks more like it was done for a feature than for TV. And that same tightly wound filmmaking is no less present.

Given all this, Kon’s struggle with Paprika wasn’t just a matter of the imagery. It was the logical end of a process he’d been developing since the ‘90s. In the Paprika footage above, you can see Kon tracing over his sketches with clean ink lines, like he’s readying a manga page for publication. Tokyo Godfathers had a believable claim to the most intricate storyboards in anime history, until Kon himself dethroned it.

It’s not clear how far Kon could have kept pushing this style. The last film he released, the 2008 short Good Morning, used 17 pages of storyboards for a single minute of animation. It consists of a woman waking up and getting ready for the day. Looking at it one way, the film is more of an exercise in Kon’s storyboarding technique than it is a film.

Still, that doesn’t mean Kon’s storyboards are a dead end. We’re lucky that his four main films have seen their complete boards published as books. He may be gone, but these guides to filmmaking live on. Even if you don’t follow his technique to its natural conclusion, even if you don’t storyboard at all, Kon’s boards have lessons to teach. Lessons about art and storytelling — and about how far some perfectionists are willing to go.

2. News around the world

An impressive showing in the Bay Area

This week, we were lucky enough to catch the Bay Area International Children’s Film Festival. It was a virtual event this year, powered by streaming. The format didn’t hurt it — we found BAICFF to be a well-curated showcase of animation, both local and global.

Umbrellas was one standout. Funded through Kickstarter, this is a French-Spanish co-production we hadn’t seen before. It follows a girl’s effort to grow and overcome trauma — in a Seussian world where babies and young animals arrive in baskets flown by umbrellas. That premise becomes a potent metaphor as the story unfolds.

Two other highlights were Am I a Wolf? (Iran) and Shooom’s Odyssey — a wonderful CG short from Europe, about two little owls surviving after a storm. It’s clear why Shooom’s has been cleaning up at festivals. The short turns the clichés of 3D animation upside-down, from color to shape to motion. “Everything was quite difficult,” producer Claire Paoletti said, during one of BAICFF’s great behind-the-scenes chats. We believe her.

Despite this stiff competition, the Bay Area held its own. Some of BAICFF’s best material was local — like Baba Yaga, the VR film that won two Emmys this month. The piece is thrilling, moving proof that VR filmmaking isn’t just a gimmick. Another highlight was Acorns, an adorable short series by Tonko House. And the previews of The Inventor, a stop-motion film by event organizer Jim Capobianco, left us intrigued.

Jujutsu Kaisen continues its takeover

The anime series Jujutsu Kaisen premiered last October. Since then, its popularity has exploded. According to a new report by Animation Business Journal, the series was Japan’s most-streamed program from January through June 2021. Not even Demon Slayer could compete. (Notably, animated programs made up 16 of the top 20 slots.)

Jujutsu Kaisen’s chart position doesn’t come as a total surprise. A few weeks ago, Animation Business Journal wrote that the series has helped to drive the post-COVID rebound of its distributor, Toho, alongside hits like My Hero Academia. Toho’s now betting big on the Jujutsu Kaisen feature film, Jujutsu Kaisen 0, out this December.

Keep in mind that Toho’s profits don’t come from streams alone, or even primarily. The popularity of Jujutsu Kaisen has meant licensing deals — a flurry of them, at home and abroad. Back in April, the series picked up a major prize at Japan Character Award 2021, a licensing award show that recognizes the most active Japanese brands. Jujutsu Kaisen already had 70 licensees at that time, and it was growing at a record rate.

Best of the rest

This week, Netflix declared The Mitchells vs. the Machines its biggest animated film launch to date — 53 million households watched it in the second quarter.

Amazon is making moves in Japan. It’s created a prize to fund and snap up new talent at the prestigious Tokyo International Film Festival. Meanwhile, it spent an undisclosed (large) sum on the global distribution rights for Evangelion 3.0+1.0.

Demon Slayer the Movie continues to break Japanese records. Now, it’s become the first DVD since 2004 to spend five straight weeks atop Oricon’s weekly sales list.

In a final Japan-related story, the reckoning over labor rights continues. Anime News Network peeked into conditions at Science SARU — and all was not well.

A student animation celebrating China’s 56 ethnicities enchanted the Chinese internet last month. This week, Wuhu Animator Space talked to its creator. (See the film on Bilibili — the blue switch at the bottom disables scrolling comments.)

The Vancouver Animation School is starting a training program in Brazil this September. In the lead-up to that, it’s doing free Zoom workshops from July 31.

The Indian animation house Cosmos-Maya has reportedly obtained the entire IP catalog of Lotpot Comics — India’s venerable comics magazine. The move comes a few weeks after Cosmos-Maya sold to NewQuest Capital.

Here’s an odd one. Russia will boast Europe’s only theatrical run of Hasbro’s upcoming My Little Pony film. It seems Hasbro scored big in Russia last year with the series Pony Life.

On the heels of Russia’s Key Buyers Event in June, the country made more waves at the Marché du Film in Cannes this month. Russian animation houses, backed by the government, secured another batch of international partners.

3. Quick look back — Munro

The Academy waited a long time to recognize foreign-made animation. After the Oscars introduced an award for short cartoons in 1932, it went exclusively to American studios — for years. Then, in 1961, that streak was broken by the Czech film Munro. The thing is, people were under the impression that Munro was from the States, too.

And the film did begin its life there. In the ‘50s, the New York director Gene Deitch had tried to turn Munro’s original comic into a cartoon — its author, Jules Feiffer, even did a storyboard. But the film was too contentious to find backers. It’s a searing antiwar satire about a four-year-old boy who’s drafted by mistake. In a catch-22 story before Catch-22, no one believes he’s four, because four-year-olds can’t be drafted.

Munro got made through the secret arrangement that later let Deitch produce Tom and Jerry cartoons behind the Iron Curtain. He went to communist Czechoslovakia — and worked with the state-run animation studio Bratri v Triku. In his book How to Succeed in Animation, Deitch recalled bumping into a strikingly different work culture there:

There was a continuity of work we Americans could never imagine. In America, I never worked anywhere for more than four years. Working at the Bratri v Triku studio in Prague in those days was virtually a lifetime annuity. True, the pay was lousy, but the work was steady, basic living was cheap, and there were perks.

Despite the language barrier, Deitch and the Czech animators made a classic with Munro. It’s a near-perfect recreation of Feiffer’s comic, in both style and script. But the Czechs’ involvement was kept under wraps — a harsh reminder of the political climate during the Cold War. Rembrandt Films, an American company, took credit for Munro.

The film had its Oscar-qualifying run in Los Angeles during late 1960, after a nail-biting race to the finish. Not only was it nominated — it won. But the landmark went widely overlooked. (Many saw Yugoslavia’s Ersatz, which won the next year, as the first foreign cartoon to win an Oscar.) In 1961, Munro had its wide release in front of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Below, you may find that the pre-show cartoon holds up better:

4. Last word

And that’s it for this week! Thanks for sticking around. We’ll be back next Sunday with another batch of animation highlights from around the world.

If you liked this week’s edition, feel free to spread the word! Every share and forward helps us reach more eyes and bring the huge, vibrant world of animation to more people each week.

Hope to see you again soon!

Kon's storyboarding was impressive (I'm struck by how wildly differently artists work) but I was delighted to discover Munro—what a hilarious and also strangely poetic piece of work. "I'm only four!" "How long have you been feeling this way?" 😭❤️

The voices were incredible. Makes me miss old films—the elocution was totally different back then. Arguably so much better, more interesting...

I'm so curious about your process for discovering/selecting work to highlight in your issues—and how long it takes to write a weekly post.