Welcome back to the Animation Obsessive newsletter! We’re glad to have you. Here’s our agenda for today:

One — animation news from around the world.

Two — the filmography of Don Bluth, revisited.

Three — the retro ad of the week.

Four — the last word.

If you’re new around here, don’t forget to sign up for free. Our newsletter comes out every Sunday, and you’ll never have to worry about missing an issue:

Now, let’s go!

1. Headlines around the world

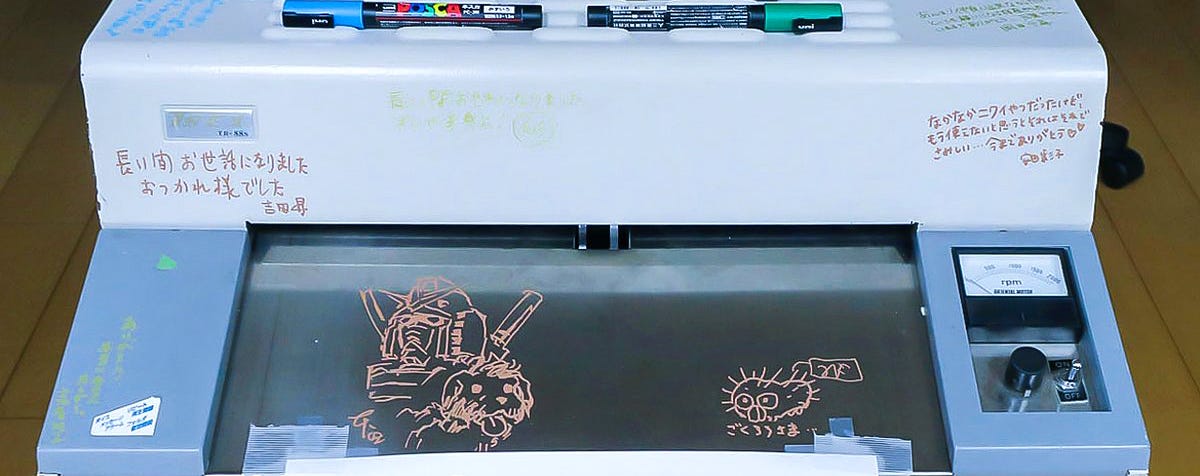

Studio Ghibli’s vintage copier breaks (and goes viral)

It’s an unlikely story, but Studio Ghibli’s old copier broke and caused a stir in Japan this week. The news spread so widely on Twitter that the press reported on it. If you look closely, though, it makes sense. The device is a glimpse at animation history, and at a world disappearing piece by piece.

On Twitter, Ghibli wrote that the so-called tracing machine used at the studio for “many years” had broken down. Because the technology is out of date, and has been discontinued for so long, Ghibli couldn’t find replacement parts this time. Hayao Miyazaki, Takeshi Honda and other Ghibli staffers left messages and doodles on the machine, thanking it for its service as it goes into storage.

Even in Japan, the tracing machine is a relic of the past that few understand. Computers replaced it decades ago at most studios. The device is somewhat like the Xerox machines used by Disney on films like Dalmatians and The Rescuers. It transfers animators’ pencil drawings from paper onto cels, where the art can be painted and readied for the camera. But the result is much cleaner than Disney’s method.

Toei Doga spearheaded the technology back in the 1960s. Unlike Xerox, tracing machines are heat-based and react specifically to the carbon in graphite pencil lines. When used correctly, they avoid the scratchy look of Xerox — among other benefits. The downside is that the finished cels deteriorate. (You can read more in Japanese-language articles by Masahiro Haraguchi and Ryūsuke Hikawa.)

Ghibli was an early adopter of computers in anime, using them heavily for Princess Mononoke. It’s odd to see an active-duty tracing machine at the studio. But Ghibli wrote on Twitter in February that it was still using the devices to create specific effects — even though the latest model was discontinued 20 years ago.

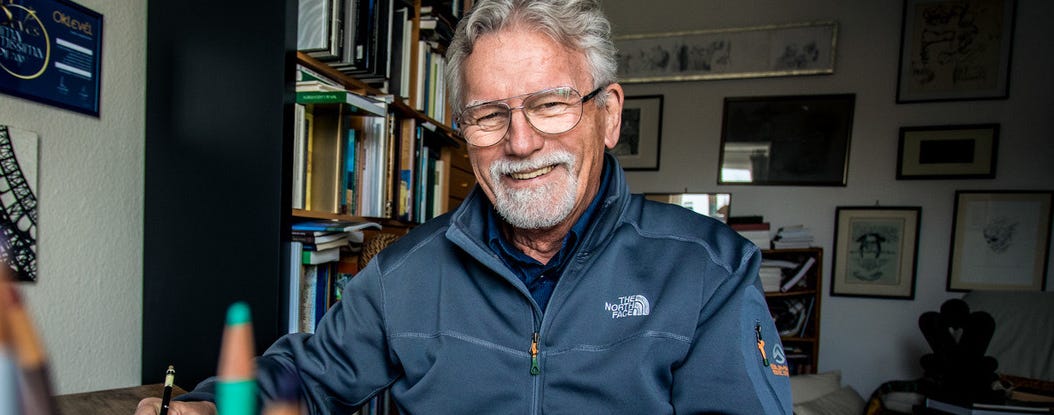

Hungarian master Marcell Jankovics, 1941–2021

This week, animation lost a giant. Hungary’s Academy of Arts reported yesterday that Marcell Jankovics, director of films like Son of the White Mare and The Tragedy of Man, had passed away at the age of 79. Jankovics was the most iconic figure in Hungarian cartoons, and one of the last living masters of Eastern Bloc animation — a small group that dwindles each year. At home and abroad, he loomed large.

According to the Academy, Jankovics started his animation career in 1960, after a childhood overshadowed by trauma and the political persecution of his father. He worked at the state-run Pannonia Film Studio in Budapest — learning from some of the nation’s top animators. In his early years at the company, he labored on short films and TV series like Gustav.

Jankovics solidified his reputation with the bright, trippy Johnny Corncob (1973) — Hungary’s first animated feature. It was a hit that spread far beyond his homeland. The following year, he released a short called Sisyphus that received an Oscar nomination. And he oversaw Hungarian Folk Tales, a successful TV series, from 1977 until 2002.

One of Jankovics’ best-known films overseas is Son of the White Mare (1981), a psychedelic epic that Arbelos recently remastered in 4K. Another world-famous work, The Tragedy of Man, began production in 1988 but took over 20 years to finish. The end of communism and state funding left it in limbo, not unlike Yuri Norstein’s The Overcoat. Critics raved when it debuted in 2011.

BUSINESS: Amazon buys MGM

On Monday, the pseudonymous writer Film Crit Hulk published a behind-the-scenes account of the recent slew of media mergers. That includes Warner with AT&T, Fox with Disney, Warner with Discovery and so on. It’s a harrowing read that insiders have praised for its accuracy. This week’s top business story ties directly into it.

On Wednesday, Amazon reached an $8.45 billion deal to buy out MGM — the rightsholder of James Bond, Rocky, The Addams Family and more. It’s a clear move in the streaming wars, but it’s less about legacy film and television and more about IP, the media world’s main currency. The Prime Video VP hyped up “the treasure trove of IP in the deep catalog that we plan to reimagine and develop.”

Animated classics are part of that catalog, including The Pink Panther, The Secret of NIMH and more. That doesn’t count possible animated spins on live-action properties — even Better Call Saul has one, these days.

The Verge questions the logic of Amazon’s move from a numbers angle, but Film Crit Hulk lays out the bigger problem. Each of these mergers leads to fewer workers doing more work. And, compared to the Hollywood system, the production side of streaming favors lower wages and non-union teams. Given its history, Amazon buying MGM “signals the most dangerous shift with what is about to happen regarding labor.”

Best of the rest

American actor Samuel E. Wright, voice of Sebastian in The Little Mermaid, has passed away in his 70s. The BBC rounds up the tributes to him.

Demon Slayer the Movie topped $45 million in North America, the second-largest haul for a Japanese animated film. ANN looks at the film’s success by region.

Also in Japan, The Crocodile Who Lived for 100 Days has been pushed back to July 9. It was due this week, but issues with COVID-19 delayed it.

To spur animation in Russia, Moscow’s local government has introduced a new grant program worth 100 million rubles. Grants per studio go as high as 10 million rubles, or around $137,000.

Two contests for cartoons by young people, Russia’s Firebird Festival in Novosibirsk and Britain’s Young Animator of the Year awards, are set for the middle of 2021.

You may not know the American series Pencilmation, but it’s likely bigger than your favorite show. This week, creator Ross Bollinger showed off his next project.

2. Rewatching Don Bluth

The films of Don Bluth get a lot of flak, but it’s a mistake to write him off. He started his studio in a garage — and nearly stole Disney’s throne. He broke serious ground with The Secret of NIMH. He was an early video game pioneer with Dragon’s Lair. And he jump-started Irish cartoons when he moved to the country. Even the founders of Cartoon Saloon learned animation through a program Bluth created.

Lately, we’ve been revisiting Bluth’s work — both the good and the not-so-good. The duds in the bunch are still worth engaging with. If you’d like to join us, you’ll find his films linked in our round-up below. They’re scattered across every service under the sun.

First off, The Secret of NIMH is free on Tubi with no account required. The platform also offers free access to The Land Before Time, All Dogs Go to Heaven and Rock-a-Doodle. Meanwhile, Peacock lets you watch An American Tail by signing up for free. (Note that Netflix has All Dogs and The Land Before Time as well, if you prefer.)

The rest of Bluth’s films aren’t free, unless you count free trials. His two director credits at Disney, The Small One and the animation for Pete’s Dragon, are on Disney+. Thumbelina and Anastasia have ended up on Disney’s service, too, for some reason. The much-maligned Pebble and the Penguin is on Prime Video — and Starz has Titan A.E. and A Troll in Central Park.

There’s just one major oversight in all this. Banjo the Woodpile Cat, the film that started Bluth’s independent career, is nowhere to be found. We have a DVD copy coming in the mail.

3. Retro ad of the week

Old animated commercials can teach us a lot — and not only about animation. These ads were made to influence people, and that’s exactly what the successful ones did. They’re a window into what viewers related to, into what aesthetics captured their eye. And, in the spots of John Hubley’s studio Storyboard, what made them laugh.

During the mid-1950s, Storyboard landed a hit with John & Marsha — a TV commercial for Snowdrift shortening. It premiered in the first half of ‘56, winning a top award from the Art Directors Club of New York. Viewers were smitten, too. “Of the 80 stations that have carried the Snowdrift ad,” Sponsor Magazine disclosed, “75% have reported requests from listeners asking when it would be on the air next.”

Credit goes to the spot’s “real socko entertainment,” as one Storyboard rep put it. John & Marsha presents a common gag from commercials of the day — a beleaguered wife overcoming an insensitive husband. It’s based on a then-popular novelty record made up of the words “John” and “Marsha” in varying tones. Storyboard adds “Snowdrift” and flips it into an ad. Fluid, expressive animation by Art Babbitt ties it together.

One bit of interesting minutia about John & Marsha is that it was censored. In late ‘55, the sponsor declared its ending “too suggestive” — which outraged Babbitt. The final scene in the version embedded below was a late addition. Yet a seemingly unedited John & Marsha reel has made the rounds online for years. Compare for yourself.

4. Last word

That’s that! We hope you’ve enjoyed this week’s edition.

One last thing. If you liked our write-up on Yuri Norstein a few weeks ago, the master animator recently conducted a Zoom meeting about his career and films with Pushkin House in London. It’s packed with insights and rare artwork — especially from The Overcoat. Check it out on YouTube.

Hope to see you again soon!