Welcome! The Animation Obsessive newsletter returns with another batch of highlights, news items and tidbits. Here’s the slate:

1 — what Dreaming Machine was going to be.

2 — animation news worldwide.

Our newsletter goes out every Sunday and Thursday. If you haven’t already, you can sign up for free to receive our Sunday issues right in your inbox, every weekend:

All set? Let’s go!

1. Inside Dreaming Machine

Satoshi Kon, one of the best directors ever to work in anime, passed away in August 2010. He was only 46.

During his short career, Kon never made a big hit — but films like Perfect Blue and Paprika took on legendary status with time. He grew widely influential. And, before his death, he was working on the film that could’ve taken him into the mainstream.

You’ve probably heard of Dreaming Machine. Kon called it “a ‘road movie’ for robots.” He started the film in the 2000s, and it was under full production when he died. There were attempts to finish it. Kon had already storyboarded it, and much of the film was animated. But it didn’t happen — Dreaming Machine likely won’t be completed.

That’s the familiar part. We wanted to know something else, though: what was Kon actually planning? What was this film supposed to be? Using Japanese books, a French documentary and several obscure online sources, we’ve pieced together a portrait of Dreaming Machine. This is the story of the film that never was.

Dreaming Machine was about the future’s future, according to Kon.

That’s a tricky concept, but you need to grasp it to understand what Kon was doing here. This is how he explained it in April 2007, while writing Dreaming Machine’s script:

The next movie I am working on is set in the future. In anime we often create a future that is near, that we can imagine, but this movie is about the future of the future, a future folklore story. From a child’s perspective it is an adventure film, while an adult may view it differently.

He got more specific in his proposal document for Dreaming Machine.1 With this film, Kon wanted to show us:

The near future that people around the world once dreamed of. A future world where transparent tubes ran in all directions between skyscrapers, hovercars came and went, and “Astro Boy,” the child of science, wielded his iron arm… This “near future that was supposed to come” has been destroyed.

Kon noted that all life had vanished in the future-of-the-future. Humans were long gone — as were animals and plants. What remained was a gutted space-age world, full of retro cars and buildings, run by robots that looked like they’d popped out of the mind of a mid-century artist.

In essence, Kon was imagining a retrofuturistic post-apocalypse. Think Fallout, but made by someone who’d probably never heard of Fallout. It was Astro Boy gone wrong.

And yet Kon was creating Dreaming Machine for a broad audience. “He was really clear […] this was a family film that he was trying to make,” recalled Aya Suzuki, a key animator on the project. Dreaming Machine’s plot moved away from the esoteric aspects of films like Paprika. Kon was entering a new stage of his career.

“Paprika marked an end to my usual themes, the blurring of reality and fiction,” Kon said while planning Dreaming Machine. We never got to see how this might’ve played out. But we do know a bit about where Kon was heading.

Sharing our newsletter is one of the best and easiest ways to support it. If you like what you’re reading, why not tell a friend?

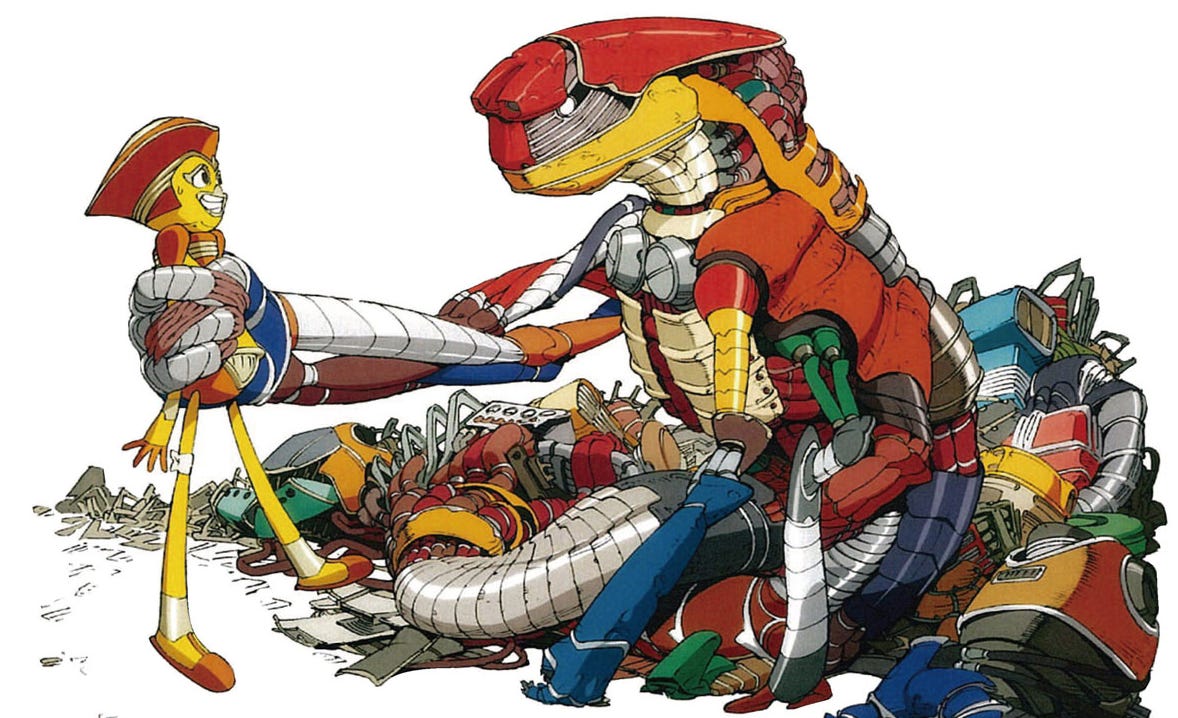

The characters in Dreaming Machine were all robots. As Suzuki said, they were leftover “machines that were created by people to do labor.” Even in a post-human world, the robots kept working.

Our story began in “a paradise of electricity,” per Kon. Early artwork depicted it as a mid-century skyscraper lined with tiled halls, large windows and synthetic plants. Only its top poked out of the water — it was a little taller than the buildings around it, the rest drowned by a risen sea. In this sanctuary, a small, headless, nameless robot lived alone.

Another robot, Lirico, washed up in paradise one day. She was a “nanny” machine, Suzuki said, who was “built and programmed to take care of children.” Lirico was styled like a “cuddly toy” by her creators. (Her design was referenced in part from an actual doll.) And Lirico got the ball rolling by giving the nameless, headless robot a name and a head. He became Robin, our protagonist.

There’s symbolism here, as Suzuki made clear. Kon saw this paradise as his film’s Garden of Eden, and Lirico as its Eve. Not long after Lirico’s arrival, she and Robin were “driven from paradise by a tsunami,” according to the lost website for Dreaming Machine.

The film’s producer, Masao Maruyama, said that this moment of Dreaming Machine eerily predicted the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in eastern Japan. “I’m starting to think that certain creators do have the ability to see what’s coming in the future,” Maruyama said.

In Dreaming Machine, life outside paradise was harsh. Electricity was scarce, and robots died without it. Robin and Lirico were in danger. But they heard about a magical “Land of Electricity” where the power never ran out, and they went on a quest to find it — joining up with a blue “combat robot” named King along the way.

It was a straightforward setup, and that was Kon’s goal. Dreaming Machine was an adventure. On their road trip across the ruined world, Robin, Lirico and King would come across odd characters and challenges — like an army that hoarded electricity. As the story progressed, Robin “grew up.” Here’s the proposal again:

… he is born as a small child. In his travels, he inherits the parts that allow him to grow from other robots of the same type, and through his experiences he develops wisdom and knowledge, growing from a “boy” to a fine “young man” robot.

This was Kon’s crowd-pleaser. The film even put music front and center. “It’s not a musical, but it can be said [to be] like a ‘music animation,’ so to speak,” Kon explained. He named the film after a song by Susumu Hirasawa, his longtime composer. In one scene, the characters danced to a Hirasawa track.

This wasn’t a safe, warm film, though. Kon never was. “When you read the script [for] Dreaming Machine, there’s quite scary stuff in it, and there’s a lot of dark points in it,” Suzuki said. “And there’s a complexity in the narrative as well.”

Dreaming Machine was entertainment, but it had teeth. It was aimed at kids (a new audience for Kon), but also at the adults who’d watched his work all along. And the film had a message, as Kon wrote in his proposal:

This work is a very simple adventure story, chiefly an entertainment film. But it doesn’t stop at mere amusement; it is also a story with substance to encourage and share with children and adults living in today’s stressful times. In this work, I would like to convey the simple and healthy way of thinking that “purpose is born by living.” Even if you don’t understand now, if you keep living, purpose and meaning will be born later. That is what humans are capable of, and it is the core theme of this work.

Dreaming Machine is sometimes (incorrectly) called The Dream Machine. It’s an important difference, because it hints at what Kon was going for. Madhouse, the studio behind the film, once put out a statement that Dreaming Machine was about “the concept of life itself generating dreams and objectives.” Not sleep dreams, but dreams-as-in-goals. Dreaming machines might just have been machines with dreams.

In this film, Kon had a project with every reason to be good. There was a strong concept and a stronger team — Kon was in peak form, and he brought along many of his top collaborators, like art director Nobutaka Ike. Plus, as Suzuki said, Kon used Dreaming Machine to train up-and-coming animators, bringing new blood into anime.

Kon’s career wasn’t done. It had barely started. The more you learn about Dreaming Machine, the clearer that gets. “Each of my previous works is indeed a memorable and meaningful one for me,” Kon said in 2007, as he prepared this film. “But if you ask me which one I love most, I’d say my next project I am already working on is the one.”

2. Global animation news

The Warner/Discovery purge

Warner Bros. Discovery has been in the news a lot — and not for good reasons. This week, the company sparked a full-fledged crisis in American animation when it started purging shows from HBO Max, YouTube and even social media. HBO Max cut Close Enough, Uncle Grandpa and many more (including 200 episodes of Sesame Street).

No one fully knows what David Zaslav, the head of Warner/Discovery, is thinking here. It’s a weird and, for creators and studios, terrifying move. And it contributes to the growing discontent in California’s animation industry.

“It’s amazing to see that almost all of the work that I’ve done in the past five years has been either canceled, had production halted or been pulled off of streaming services,” tweeted Nick Cross (Over the Garden Wall, The Clockwork Elves). “All the more reason artists should be producing their own independent work.”

Warner Bros. Discovery perceives a few benefits to these moves. CNBC reports that “there are three main motivations behind the cuts: slashing costs, moving away from content aimed at kids and families and decluttering the service.” The company saves money on residuals, at the expense of unions and their members, and gets rid of supposedly “little-watched films and shows” that choke out potential successes.

Whether these films and shows are truly “little-watched” is unknown. And decluttering is risky in the age of streaming, when many shows don’t get physical releases and can disappear forever. Even worse is the slashing of residual payments, which “actually go to our union to pay for our healthcare,” writes Infinity Train creator Owen Dennis.

In his Substack newsletter, Dennis penned the single best behind-the-scenes account of the purges so far. We recommend reading it all. In one passage, he notes:

I think the way that Discovery went about this is incredibly unprofessional, rude and just straight up slimy. I think most everyone who makes anything feels this way. Across the industry, talent is mad, agents are mad, lawyers and managers are mad, even execs at these companies are mad.

There’s a big question that everyone in the animation industry is asking about Warner Bros. Discovery, Dennis writes. “How do they plan to have anyone ever want to work with them again?”

Best of the rest

A fun American story: basketball star Zion Williamson says that “around 80% of players in the [NBA] are into anime; they just won’t admit it.”

Ten days after its premiere in Japanese cinemas, One Piece Film: Red became the most successful One Piece film to date. By the 18th, its revenue was up to almost $59 million.

At the same time, Japanese sales of anime DVDs and Blu-rays collapsed in the first six months of 2022, dropping over 54% compared to January–June 2021.

There’s a visually mind-boggling trailer for the upcoming Chinese film Deep Sea (by the director of the hit Monkey King: Hero is Back). It looks like one of those elaborate, painted posters typical in Chinese animation — only in motion.

Also in China, Variety has a wild story about two American con artists who stole hundreds of millions by impersonating a studio behind Wish Dragon. The duo was sued over it in March, but the con continues.

Russia’s Ministry of Defense created the “Fund to Support Military and Patriotic Cinema” (Voenkino) a few months ago. Now, Voenkino has plans to branch into licensing, merchandising and even animated spin-offs. Very creepy.

Meanwhile, Russian streamers like Okko are starting to lose their catalogs of older foreign film and TV — as existing contracts expire and aren’t renewed.

Starting August 26, Ukraine’s KROK animation festival is holding free events in Los Angeles, featuring Ukrainian animation old and new (and more).

A great piece from Cartoon Brew: “What Did Israeli Animators Do for Summer Vacation? They Saved Their Animation Industry.” Read it here.

Lastly, we wrote about the art of the animated music video.

See you again soon!

As published in The Anime Works of Satoshi Kon, our main source for the write-up. We also relied on the documentary Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist and the book Kon’s Works.

Gosh, Satoshi is incredible.

By far and away his little known manga, " Opus" is in my top three graphic novels. It is literally sitting on my desk right now. I flip through it often. The images of the main character falling into his comic story gives me chills. When I watch Paprika so many emotions get stirred up. The transitions in that film are mind melting. I think the good folks at Animation Obsessive just sent me down another Satoshi Kon rabbit hole.

Thanks for doing all the research and sharing the details of Dreaming Machine! It's fun to think about how that film could still come to life with the right people involved. Fingers crossed.