Welcome! We’re back with another issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. If you’re new here, we cover animation from around the globe. This is what we’re doing today:

One — unlocking the secrets of the Armenian classic Wow, a Talking Fish!

Two — the world’s animation news.

Three — a visually stunning indie highlight.

Four — the last word.

We publish on Thursdays and Sundays. You can receive our Sunday issues in your inbox every weekend by signing up to our free list. It only takes a second:

With that out of the way, here’s the issue!

1. More than just an oddity

Every few years, a certain cartoon from the Soviet Union makes the rounds online. It’s from 1983, it’s called Wow, a Talking Fish! — and it’s bizarre. Really, that’s an understatement. The film is so strange that you’d be hard-pressed to find another piece of animated weirdness in its league.

It’s about a fisherman who catches a talking fish and spares its life. After that, he meets a grotesque, evil monster in a state of constant change — a mind-melting showcase of animated transformation. The fish reappears as a human and saves the fisherman by talking extremely fast. So many gags whiz by that you can’t keep up.

Whenever Wow, a Talking Fish! resurfaces, people watch it, get bewildered, laugh and move on. And that tends to be where the conversation ends. We want to go a little deeper. What, exactly, is this film? And why?

The answer lies in a place that’s rarely associated with animation: Armenia.

Animation came to Armenia back in the 1930s, when the country was part of the USSR. It began with a little cartoon called The Dog and the Cat by Lev Atamanov — who later moved to Moscow to make classics like The Snow Queen. From this humble start, Armenia grew into one of the world’s most influential cartoon producers.

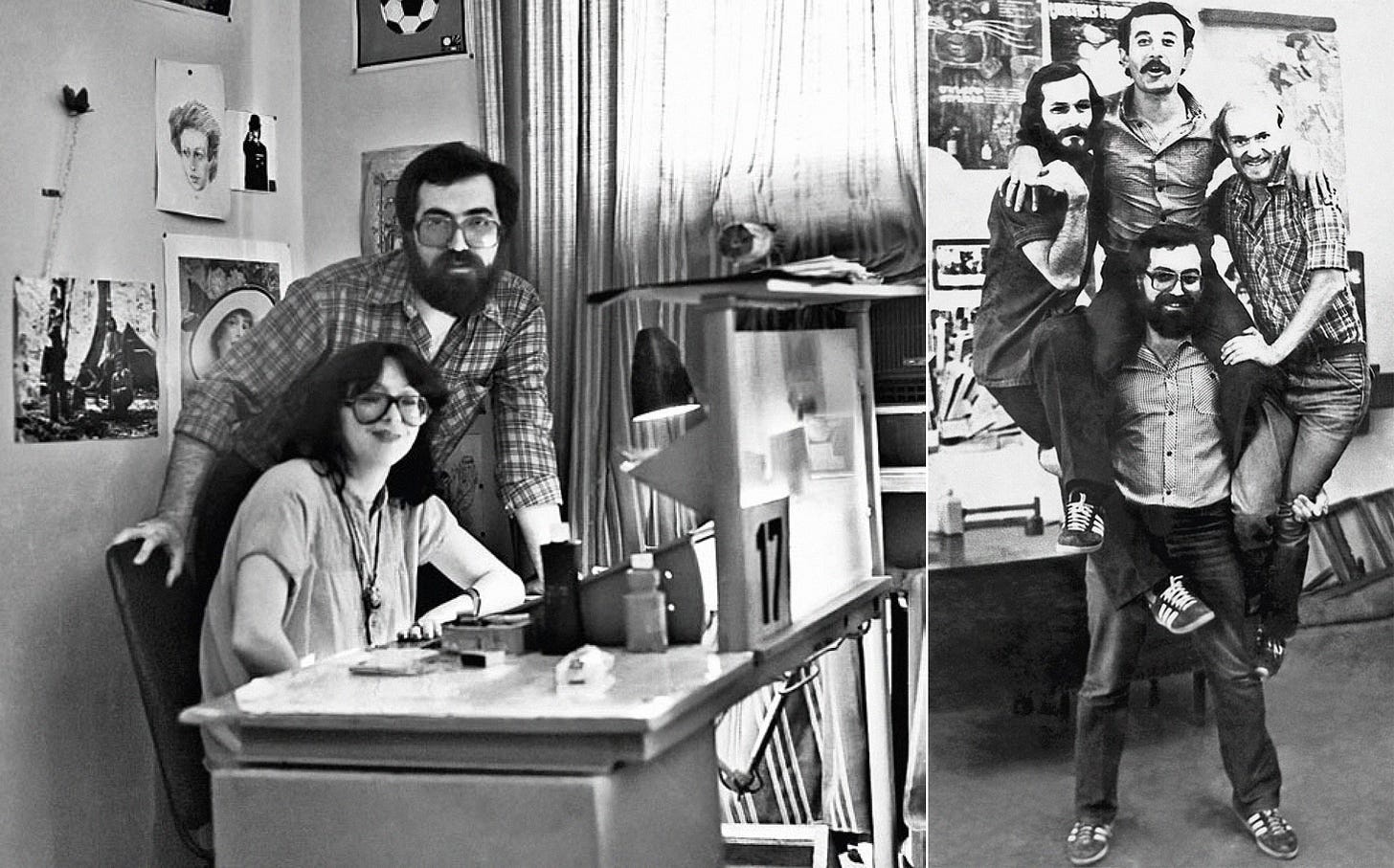

You can pin that influence mostly on a single artist — the one-of-a-kind Robert Sahakyants, director and chief animator of Wow, a Talking Fish!

Let’s get something out of the way: Wow, a Talking Fish! is purposely weird. It’s full of Sahakyants’ unique humor and animation. He was a rebel, with a hippie’s long hair and beard, who liked the trippy art and rock music that were controversial in the Soviet Union. More than once, he found himself in trouble with the government.

Like all animators in the USSR, though, Sahakyants had his work funded by that same government. He made Wow, a Talking Fish! at the state-owned studio Armenfilm, located in the city of Yerevan. Despite the oppression and incompetence of the Soviet regime, he later recalled:

… it was in those years that cinemas, art galleries and academies of sciences appeared in all the republics. Greenhouse conditions were created for the development of art and culture.

It’s that mix of artistic rebellion and institutional support that gave us Wow, a Talking Fish! — Sahakyants had the funding to be off-the-wall, but he also handed his bosses films that they often hated. This project was the most extreme version of ideas he’d been pushing for a while.

Sahakyants started at Armenfilm in 1970, around the age of 20. When he took the drawing test to join, the story goes that someone remarked, “This hippie will make a great animator.” He quickly rose to a director role because an artist above him got fired. From the start, he worked alongside his wife Lyulya (he attributed his career to her).

In 1975, Sahakyants delivered The Fox Book, a psychedelic musical that mashes up Armenian fables with modern aesthetics. It’s a clear step toward Wow, a Talking Fish! — especially in the animation, where Sahakyants’ growing knack for transformation stands out. He later called it his signature trick, citing the “huge number of transformations” he drew during this era of his career. As a pair of historians put it:

The Fox Book, made in 1975, was a shock both for Armenian and international animation. Spectators could not follow the metamorphoses of his characters; the sheer number of gags and transformations were beyond belief.

His bosses at Armenfilm didn’t get it, but they accepted it anyway. When it went higher up the ladder for approval, Sahakyants caught another lucky break — Armenia’s top censor passed it. Apparently, that official had once opposed the iconic avant-garde film The Color of Pomegranates and couldn’t afford to make the same mistake twice. “I would be disgraced for the rest of my life,” the official said.

Near misses like this one became the norm for Sahakyants. The road to Wow, a Talking Fish! was paved with them. Even as he developed his wild humor and transformation technique, and animated more and more of his films by himself, Sahakyants was battling the authorities.

His film Hunters (1977), another musical filled with rapid-fire gags and masterful transformations, never saw wide release for bureaucratic reasons. After Sahakyants made Nazar the Brave (1980), a new top censor in Armenia told him that he was “completely devoid of a sense of humor” and needed to “take a break.”

Soviet officials spoke in coded language. The censor’s meaning, Sahakyants knew, was that he’d been banned from filmmaking.

But Sahakyants found a loophole. In Russia, Moscow Central TV had just started to fund cartoons across the USSR that adapted local fairy tales. He got into the program and, still working at Armenfilm, began to churn out the run of cartoons that cemented his legacy.

Wow, a Talking Fish! was one of them. For the skeleton, Sahakyants looked to a fairy tale by the Armenian writer Hovhannes Tumanyan. It’s a simple story, and Sahakyants mostly stuck to it. But he used that structure as an excuse to get as out-there as he wanted to be.

The original story refers to the evil creature simply as a “monster,” and has little to say about it. Inside these lines, Sahakyants paints one of the great characters of Soviet animation — Ekh, a bombastic shapeshifter like no other. And what the fish says to confuse Ekh is mostly pulled from the fairy tale, but Sahakyants portrays the events literally, at a manic pace.

The film that Sahakyants created out of that little story is surreal, hilarious and, from a technical angle, just extraordinary. Only he could’ve made it.

Wow, a Talking Fish! became and remains widely popular (and widely quoted) in Russia. And it wasn’t Sahakyants’ only cartoon from the period to receive that treatment. Even more successful were his follow-ups In the Blue Sea, in the White Foam and Wow, Butter Week! — the latter of which turned into a seasonal classic on Russian TV.

Those three films have more in common than success. All of them feature the same old man and have the same instantly memorable theme song. While not all of Sahakyants’ pieces for Moscow Central TV are connected in this way, this group feels like an informal trilogy.

As Sahakyants’ star rose during this era, two historians wrote, “Each new film became an event for his growing number of fans.” Animators not just in Armenia but across the USSR admired and imitated him. Yuri Norstein considered him a friend and an almost superhuman artist. “In 1989 Robert Sahakyants, not yet forty years old, had already gained the title of master,” remarked one commentator.

And Wow, a Talking Fish! encapsulates the reasons why. This weird gem continues to jump out at almost everyone who sees it. The context in which Sahakyants made it is long gone — whether that’s 1980s Armenia, or the Soviet Union, or the censors that he was simultaneously battling and benefiting from. Only the film remains.

But what a film.

2. News around the world

The problem with kids’ animation online

In the United States, government regulations hem in preschool TV — and have for decades. There are rules that require set amounts of educational programming, and ones that limit advertising on channels aimed at young kids, among other things. This is clearly good, and it’s encouraged media companies to invest in TV that improves lives.

But what about online? As Chris Stokel-Walker recently noted in Wired, YouTube has course-corrected a bit since the height of ElsaGate a few years ago, but “even the platform’s biggest names still operate in a largely unregulated space.” He also wrote:

Propelled forward by YouTube’s algorithm, the platform’s most popular kids’ channels are now morphing into powerful merchandising machines.

See the success of the animated Baby Shark Dance video, which hit 10 billion views this week — the first YouTube video to do so. The song has, more or less, become an advertisement for Pinkfong’s Baby Shark brand. Animation Magazine painted a grim picture:

Following the global success of the original video, Baby Shark has expanded its universe beyond the internet with its own […] global merchandise licensing program, live tours throughout the world, interactive games, NFTs and more.

Effectively, it’s a vast and mostly unregulated ecosystem, and its point is to monetize young children to the greatest extent possible. Where kids’ animation on TV can’t go, online animation can. The gap is stark even within the Baby Shark brand itself. It has a Nick Jr. spin-off on TV that’s subject to greater regulations, and wholly different as a result.

A few other stories this week drove home these points. The most telling was the news of Genius Brands’ upcoming Kidaverse, built out of its existing “Kartoon Channel!” product. Per AnimationXpress:

Kartoon Channel! Kidaverse will include all the popular programs of Kartoon Channel! Today, while adding exclusive metaversal content […] including custom avatars and emojis for kids, exclusive games, branded Kidaverse VR goggles, immersive content and NFTs for kids (“KFT”s).

For good measure, Genius is also rolling out “a digital currency for kids called Kidaverse MetaBuck$,” which sounds like satire but isn’t.

If we’ve learned anything from the recent Roblox debacle, it’s that there is no bottom when it comes to online companies monetizing and exploiting kids. In the online kids’ animation sphere, we can expect these trends to continue getting worse until they’re forced to stop.

Titmouse New York unionizes

On the subject of forcing positive change, the biggest animation story of the week was the historic unionization of Titmouse New York.

“The Animation Guild announced this week that it has organized 113 workers at the Titmouse office in New York,” Variety reported, “marking the first time the guild has branched outside of Los Angeles in its 70-year history.”

This follows the unionization of Titmouse Vancouver in late 2020. Given how successful Titmouse has become, and how much of the North American animation market it controls, these are major strides. The latest win marks the first time that New York animation artists have been represented by a union in over three decades.

Best of the rest

After many years, the Canadian animator Robert Valley has released his Oscar-nominated film Pear Cider & Cigarettes for free on YouTube.

You can also stream the current Oscar contender Flowing Home, a French and Canadian co-production, for free until February 7.

In China, reports say that Encanto has “bombed,” pulling in only $5 million after a week and three days in theaters. By contrast, Coco earned $18.2 million there in its first three days — and over $189 million lifetime.

In Japan, the first Hiroshima Animation Season, co-run by Kōji Yamamura, is looking for entries from around the world. The deadline is February 28.

For fans of the American blockbuster The Mitchells vs. the Machines, Netflix currently lets you read its entire artbook for free.

Also in Japan — Toho is bouncing back from its pandemic woes. Powered by projects like My Hero Academia: World Heroes’ Mission, the company’s latest third-quarter results have blown 2020’s out of the water.

The Russian government is moving to create a holiday or memorial day dedicated to Russian animation, in its latest effort to leverage the country’s history with the medium for political and cultural clout.

Lastly, two more companies have joined the animation gold rush. First is a theater venue in Missouri. Second is Chefclub, known for cooking videos that The New York Times has called “demented” and “almost unwatchable.”

3. Indie spotlight — Genius Loci

This week, we shared a video on Twitter that resonated with people to a surprising degree. It’s a clip from the stunning Genius Loci (2019) by Adrien Merigeau, who’s also known as the art director of Cartoon Saloon’s Song of the Sea.

Genius Loci was up for an Oscar last year, and it’s both easy and tough to see why. Easy because it’s such a beautiful, creative accomplishment. Merigeau brought in a group of artists, primarily the illustrator Brecht Evens, to push the film in inventive directions. You can see the influence of modern painters like Joan Miró throughout.

But it’s tough because Genius Loci is mysterious and abstract. On the surface, it’s much less accessible than a typical Oscar nominee. And it definitely isn’t what you picture when you picture social-media virality.

Merigeau’s film clicked with people on Twitter, though, because it’s about feelings and states of mind that are relatable to many — even if the creators didn’t foresee it. Reine, the lead, is anxious and alienated. Her perception of the world is gorgeous, but everything she sees is disintegrating all of the time. Merigeau said in an interview:

In my mind, the story is about this person who is in a hostile world, in some kind of way, and who [...] entertains a spirit that makes her strong and disconnected and not vulnerable to the aggressions of the outside. And because it kind of destroys everything around her, or makes destruction look really appealing, and really beautiful, it’s a way to protect herself.

Consciously or not, Genius Loci portrays Reine’s dissociation. The spirit that dissolves her world to keep her from being vulnerable also breaks her one real connection. When the organ player Rosie appears, Reine starts to see clearly — only for her vision to fall apart again. Her very identity collapses, and she kicks herself for dropping her guard.

We shared part of that sequence on Twitter, and many saw themselves in it. “This is exactly what happens when I dissociate,” one person replied. Another wrote that the film “perfectly captures the feeling of dissociation.” Twitter, of all things, became an outpouring of love and recognition.

The main takeaway is that “avant-garde” art isn’t always as niche as we imagine. Even abstract and difficult work can thrive if it’s about real experiences. Sometimes, what drives people away is less the art and more the way we talk about it. Seen on its own terms, Genius Loci is a beautiful film for everyone — for artists and film majors, sure, but also for anyone who’s felt pain and confusion in the process of being alive.

You can watch it in full below, or through this link.

4. Last word

That’s the end for today! Thanks for reading. We’ll be back on Thursday with another batch of intriguing animation from around the world.

If you missed our previous issue, it covers UPA at its wildest — the strange, messy and often brilliant Boing-Boing Show (1956–1958). It’s unfairly ignored in the UPA canon, and we explore the reasons why it shouldn’t be. The issue looks at how the series fostered a hyper-creative environment for artists, where just about anything flew. Along the way, we share a few of our favorite segments. It’s a lot of fun.

Lastly, we were really wowed by the interest shown toward our recent piece on Mongolian animation. Thank you to everyone who’s checked it out so far!

See you again soon!

Hiroshima Animation artist residency!!! That's gold. Def applying for that. Genius Loci is freekin' amazing. The composition of the shots are inspiring. Thanks for sharing!!