Welcome! We’ve got an exciting edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter lined up for you this week.

First, we’re looking at one of the most influential but least recognized cartoons of the 1950s — The Four Poster. It was John Hubley’s final work at UPA, and it paved the way for an entire school of cartoons. After that, we’re breaking down the week’s top animation stories and giving you two Satoshi Kon projects to stream.

If you’re just dropping by and haven’t signed up yet, there’s no time like the present. Our newsletter pops into your inbox every Sunday with a new batch of animation highlights — for free.

With that out of the way, we hope you’ll enjoy!

The Four Poster’s hidden impact

Animation has always been international. Even back in the 1930s, animators at Disney and Soviet studios cross-pollinated. Later, Japanese animators borrowed from both groups. Hayao Miyazaki calls the Russian Snow Queen his favorite film.

The modernist cartoons of UPA had international origins, too. Early Soviet animation was “a big influence on us guys who later became UPA,” John Hubley once said. Czar Duranday was a game-changer for Hubley and the others — a film “so modern and fresh [that] violated so many of the totems.”

Hubley and UPA left their own mark on global animation. But one of their projects, especially, had an outsize impact. You might not know of The Four Poster, but the history of cartoons would look very different without it.

Released in 1952, The Four Poster was Hubley’s last job at UPA, and it isn’t quite a traditional cartoon. Instead, it’s a series of animated interludes for a live-action film by Irving Reis. The live-action parts play out in a single bedroom — Hubley directed the outdoor sequences.

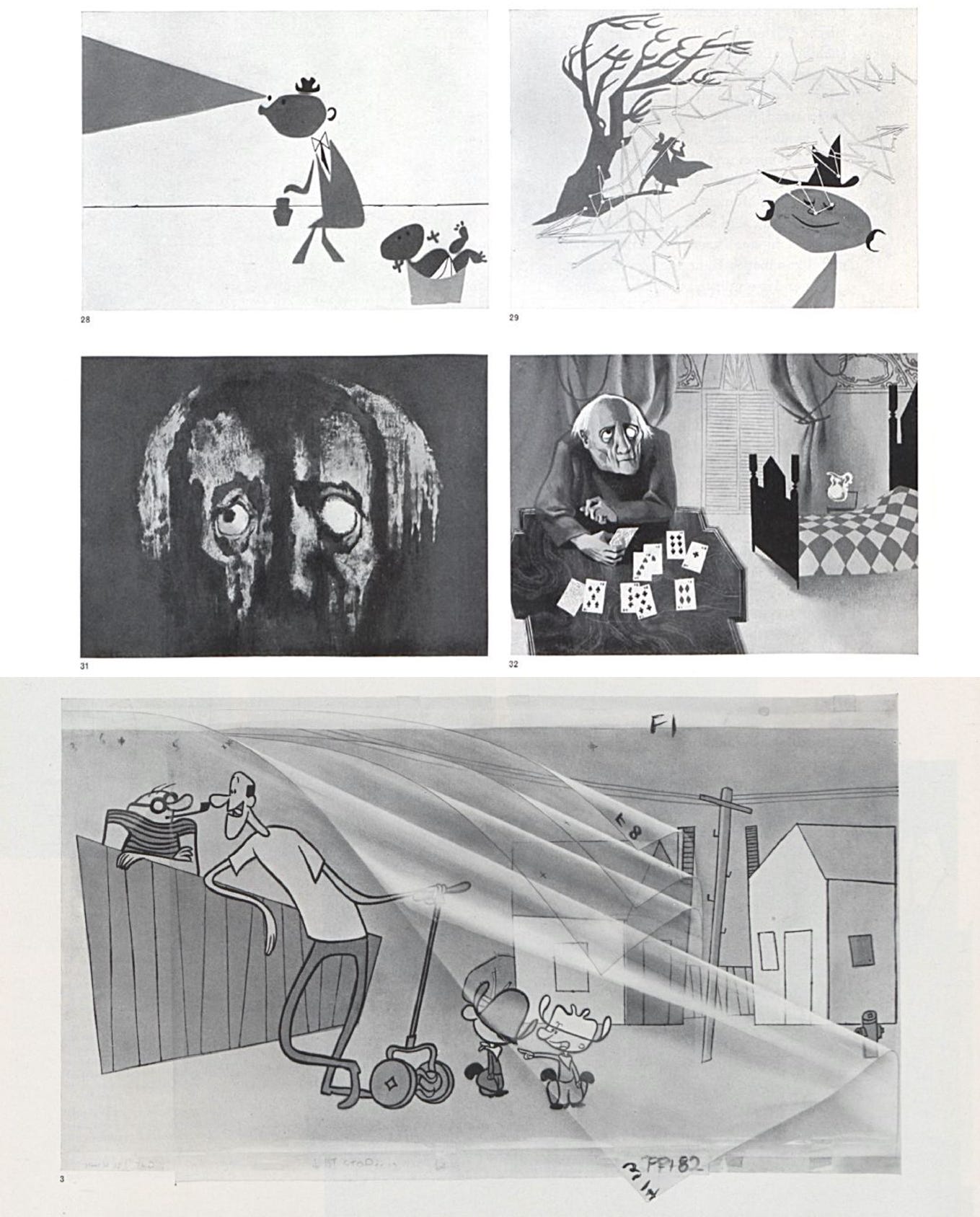

UPA’s animation comprises roughly 13 minutes of The Four Poster. Here’s how Adam Abraham describes it in his authoritative When Magoo Flew: The Rise and Fall of Animation Studio UPA:

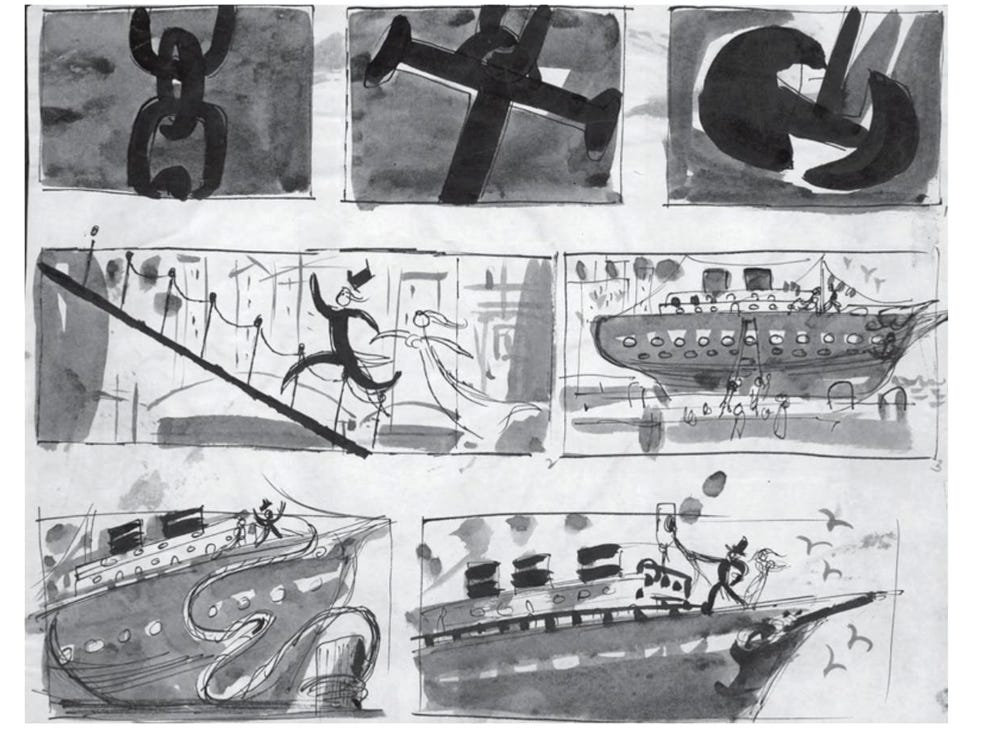

The opening titles and six interscenes that UPA produced for The Four Poster are in some ways the studio's finest film — certainly its most dazzling work in black and white. Hubley and several of the artists from Rooty Toot Toot segued to the Kramer picture; they were also joined by Lew Keller, another alumnus of the Walt Disney Studio strike. Production manager Herb Klynn recalled that each of the interscenes had its own unit. Just as Rooty Toot Toot competed with Gerald McBoing Boing, these interscenes try to top one another in kinetic brilliance and cinematic invention.

The Four Poster runs the gamut stylistically. On occasion it’s darker and more ironic than anything else Hubley directed at UPA. The studio eschewed violence as a rule, but the Roaring Twenties sequence (starting at 7:57) kicks off with a hilarious gag about gangsters shooting each other across a dancefloor. Later on, a jazz band plays atop a biplane — only to be engulfed in flames.

The World War I sequence by Paul Julian (starting at 6:54) has a jagged, expressionistic style and an emphasis on cross-dissolves. One member of UPA called it “the exploration for The Tell-Tale Heart,” possibly Julian’s definitive statement at the studio.

But The Four Poster’s most ambitious moment comes near the end. Animated by Art Babbitt, the vacation sequence (starting at 9:34) packs some of the slickest character animation in UPA’s history. It pushes forward many of the ideas from Hubley’s Rooty Toot Toot in fresh, exciting and unexpected ways.

Stunning though it was, UPA’s work didn’t save The Four Poster from obscurity. The film nabbed an Oscar nomination but reportedly wasn’t a big success — and there’s still no official home media release. As for Hubley, the Hollywood blacklist got him fired from UPA even before The Four Poster’s premiere. Neither he nor UPA made a film that looked exactly like it again.

An ocean away, though, the project found an unexpected group of fans.

It was around 1953. A shipment of American film reels arrived in Yugoslavia, a communist nation that’s today split into countries like Croatia and Serbia. The films had been “sent for possible sale to Yugoslavia,” per historian Ronald Holloway — and The Four Poster was among them.

At the time, a Yugoslav animator named Dušan Vukotić was hunting for inspiration. He’d had limited success with his early films like How Kićo Was Born (1951), drawn from Fleischer and Jiří Trnka. Seeing UPA’s cartoons in the design magazine Graphis had intrigued him, but he and his co-workers couldn’t figure out how they worked. That is, until they encountered The Four Poster.

“Hubley told me that the film went to Zagreb but disappeared for a week,” the late Michael Sporn wrote in 2006. “The animators studied every frame, then returned the print to the exhibitor — suddenly ‘found.’ ”

As Holloway explained it:

The Graphis article on the style of UPA animators was, at first, a puzzler; the mystery, however, was solved by a study of the animation-bridges contributed by John Hubley, UPA's key individualist, to Irving Reis’s The Four Poster. It was enough to encourage Vukotić and his colleagues to go back to their home-made camera (a rewired aeroplane engine) and develop a style of their own known as ‘reduced animation.’

Reduced animation wasn’t just a cost-saving measure. It was a way to create bold, original motion by breaking the bonds of realism — as UPA had done in The Four Poster. The Yugoslav method was a “protest,” as they later said. It was about bringing “life and soul to a design, not through the copying but through the transformation of reality.”

In their view, animation captured the warmth of life only if you added creativity to the mix — aping the real world gave you cold and sterile movement.

After a few years in advertising, Dušan Vukotić and his associates set up an animation branch inside the state-funded Zagreb Film. Their first project, The Disobedient Robot, debuted in 1956. And so began one of the most adventurous and influential runs in animation history.

Yugoslavia rocked Europe with its wild, colorful cartoons. Although its animators borrowed tricks from the UPA playbook, their work was firmly adult-oriented — and unapologetically weird. The surreal, violent Concerto for Sub-Machine Gun (1958) is like the gangster gag from The Four Poster taken to the furthest possible extreme. Alone, from the same year, is a dreamlike and melancholy journey into loneliness.

Vukotić directed a large portion of Zagreb Film’s animation, joined by auteurs like Vatroslav Mimica. It wasn’t long before the group started to clean up at festivals in Berlin, Oberhausen and Venice. At the Cannes Film Festival in 1958, critic Georges Sadoul dubbed their style the “Zagreb School of Animation” — and the name stuck.

As early as 1959’s Cow on the Moon, cartoons in the Zagreb School were up for Oscar consideration. Then, with Ersatz in 1961, Vukotić became the first non-American director to take home an Academy Award for animation.

Yugoslavia’s unique spin on cartoons seeped into animation worldwide. Its influence in Europe was easy to spot. Without the Zagreb School, it’s hard to imagine the innovation in style and subject matter that Russia experienced in the 1960s. Even the UPA-inspired American cartoons of the ‘90s, like Dexter’s Laboratory, have a bit of Zagreb spirit inside them.

If it’s hard to picture animation without the Zagreb School, it’s just as hard to picture the Zagreb School without The Four Poster. It’s an open question what would have happened if Hubley’s project hadn’t acted as a Rosetta Stone, helping Vukotić and the rest decipher those images from Graphis.

Without the Roaring Twenties sequence, would Yugoslav cartoons have been quite so anarchic and satirical? Without Babbitt’s animation in the vacation sequence, would they have moved in such clean, precise ways? It’s hard to say. We can say, though, that The Four Poster has earned its spot in history as a paradox — a cartoon as influential as it is unknown.

Headlines of the week

Satoshi Kon documentary details

An upcoming French documentary is set to cover the late filmmaker Satoshi Kon. Satoshi Kon: la machine à rêves (The Dream Machine) was teased last year, but more details and a full trailer emerged this week.

From director Pascal-Alex Vincent, Satoshi Kon: la machine à rêves draws on archival footage and new interviews with Kon’s collaborators. Vincent will also include scenes from The Dream Machine, Kon’s unfinished final film. Per Animation Magazine, Vincent made the documentary “in close collaboration with the subject’s widow, Kyoko Kon” — a figure who’s often overlooked in conversations about her late husband.

There’s no release date yet, but the documentary is reportedly coming soon. We’ll be watching for more.

Netflix bets on anime

It’s almost a weekly news item — streaming platforms continue to drive huge orders for new animation. This week, Netflix revealed a slate of 40 original anime set to debut in 2021. That’s nearly twice what the service launched last year.

Netflix is leaning into anime as part of its growth strategy in Asia, where competition is increasing from Disney+ and Prime Video. The platform reports that anime viewership “has been rising about 50% a year,” per The Japan Times. Its recent original anime Blood of Zeus was apparently a smash hit.

Among the Netflix headliners will be Yasuke, Eden and The Way of the Househusband. In a sign of Japan’s increasing use of foreign talent, the first two series are spearheaded by Americans — LeSean Thomas and Justin Leach, respectively.

Russia wraps up Suzdal animation festival

In Suzdal, the Open Russian Festival of Animated Films concluded this week. The Nose or the Conspiracy of Mavericks claimed the Grand Prix. This is the latest film by Andrei Khrzhanovsky — a Soviet-era luminary now in his 80s.

Backed by the Ministry of Culture, the Suzdal festival is Russia’s chief animation contest. Proceedings were held mostly online this year. Alongside its awards ceremony, ORFAK worked with the studio Soyuzmultfilm to field pitches for prospective animation projects. The short film The Man Behind the Curtain and the series The Last Bookstore won out, and will go into development at Soyuzmultfilm.

This year’s pitch jury included Svetlana Maksimchenko, a top member of the Ministry of Culture. She was so impressed by Suzdal’s face-to-face pitch process, she said, that the Ministry of Culture will be shifting away from written pitches for animation. The move could empower Russian animators as they try to sell the government on their projects — money from the Ministry of Culture plays a crucial role in the field.

What’s streaming

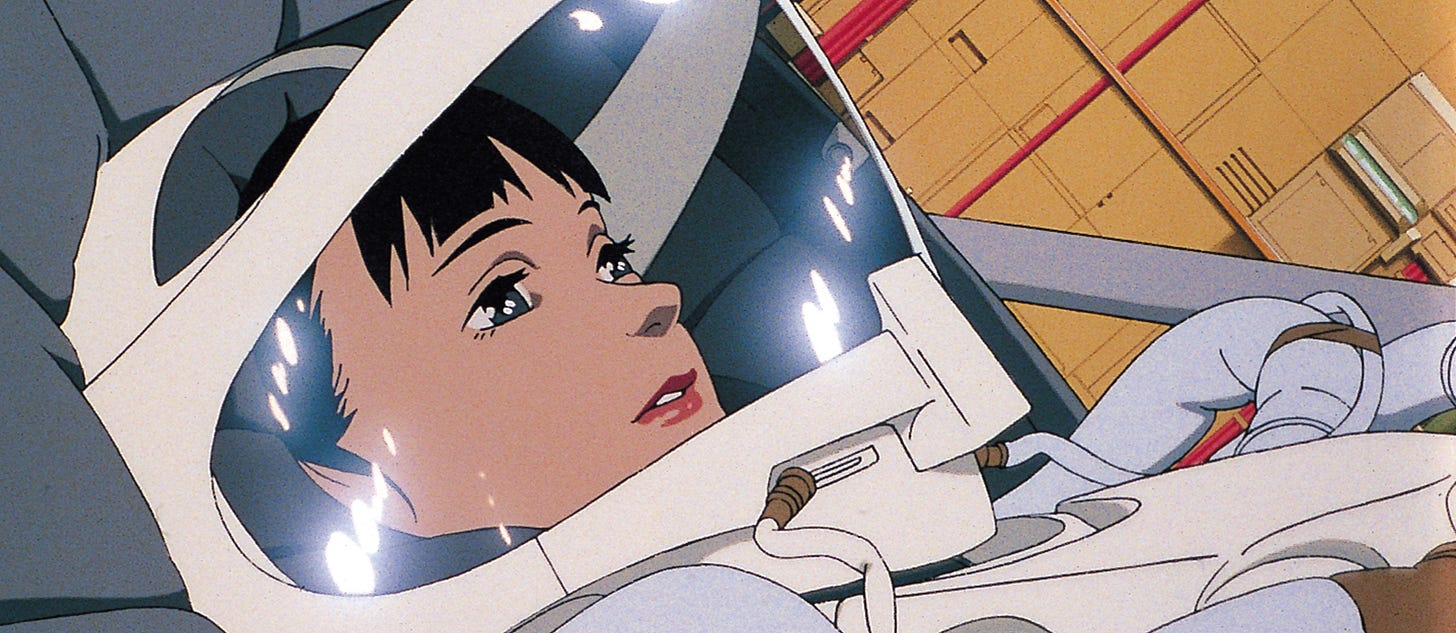

Millennium Actress (2001)

If the news of Satoshi Kon: la machine à rêves has you wanting to revisit Kon’s films, you’re in luck. Amazon Prime Video recently started streaming Millennium Actress. For those who haven’t seen it, this is a kaleidoscopic blend of Japanese history and cinema, telling the story of an elderly actress named Chiyoko. It’s also Kon’s most all-ages project — a fine introduction for those hesitant to dive into his darker work.

Paranoia Agent (2004)

Millennium Actress isn’t the only Satoshi Kon classic streaming right now. If you want more, Paranoia Agent lets you watch the master director weave together dozens of lives into one of the most original TV anime ever made. Bear in mind that this series tackles some very, very sensitive topics, though. You can watch Paranoia Agent for free via Funimation, but you’ll need an account to get past the mature content warning.

Last word

That’s a wrap! We hope you’ve enjoyed this week’s installment.

If there’s something you’d like to see us cover in the future, we invite you to leave us a comment. We’re always expanding our base of sources for international animation and animation news — and we’d love to hear your tip.

Until next week!

I’m only picking up on this material late after subscribing relatively late. Interesting to see if any of the anticipated news items actually landed by mid 2023.

Great write-up. Always interesting to see how closely related art-movements happen to be. Especially when they are as "hidden" as this one.

Regarding suggestions: It'd be interesting to see more indepth write-ups on the likes of Georges Schwizgebel or Garri Bardin. Schwizgebel's latest short is currently streaming on rts.ch - probably one his weaker works, yet still brimming with undeniable qualities (also won Best Animated Short at the Swiss Film Festival last week) -, the remainder of his oeuvre is available on VimeoVOD. Notwithstanding the above, a profile on Bardin, or an indepth analysis of his shorts "Выкрутасы" & "Серый волк энд Красная шапочка" would be appreciated. Despite being the most proficient stop-motion director to have ever lived (e.g. uses vast array of different techniques; very intelligently packed political commentary), he seems to be comparitively unknown and -recognized.