The Very First 'Madeline' Cartoon

Plus: Japanese indie animation, retro ads and global animation news.

Welcome to another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter! We’re glad you could join us. This is our agenda for the week:

One — a look at how UPA created the first animated Madeline.

Two — interesting animation stories from around the world.

Three — a trove from master independent animator Koji Yamamura.

Four — the retro ad of the week.

Five — the last word.

For those new to our newsletter, it goes out once a week. Signing up is free — and it only takes a second. Get new issues right in your inbox, every Sunday:

Now, let’s go!

1. Animating Madeline

UPA was the animation house to beat in the early 1950s. Its cartoons were new — full of new design, new types of motion and new stories about modern life. When UPA’s Gerald McBoing-Boing won an Oscar in 1951, it grew clear that older competitors like Disney needed to reassess.

The artists at UPA could copy any style of painting or illustration — and then make it move. “The whole idea was to bring those drawings alive,” artist Jules Engel later said. Even an illustrator as unique as James Thurber did a cartoon with UPA. If any team was going to figure out how to animate Madeline, it was this one. And that’s what it did.

When UPA decided to adapt Ludwig Bemelmans’ series, only one Madeline book existed. But the team had a “real love” for it, according to the film’s director Robert Cannon. Known to friends as “Bobe” or “Bobo,” he was by all accounts a gentle and sensitive man — and an enormous talent. Shamus Culhane remembered an early encounter with him:

He was sitting at his desk like a little chubby Buddha, effortlessly turning out some of the most dazzling drawings I have ever seen. As I flipped one scene Bobo watched me anxiously. “You think it’s going to be okay?” he asked timidly.

In Engel’s view, Cannon was an intuitive artist always hunting for new ideas. Animator Alan Zaslove recalled his “understanding [of] the flow of things.” That openness and sense of flow are at the forefront of Madeline. UPA’s goal was nothing less than to stick “as closely as [it] possibly could” to Bemelmans’ book, Cannon said. A tall order, given that nothing about Madeline’s impressionistic style or structure resembles a cartoon.

To capture Bemelmans’ storybook pacing, UPA used a technique that Cannon had perfected in Gerald — seamless transitions from one scene to the next. The backgrounds change, but the characters keep moving in a steady rhythm. And, like in the book, the girls flow through the world “not as individuals but as a single unit,” as Adam Abraham writes in When Magoo Flew: The Rise and Fall of Animation Studio UPA.

Bill Melendez, director of A Charlie Brown Christmas, animated much of Madeline. It’s done in the so-called “limited” style, although Jules Engel later bristled at that label. He argued that Disney’s animators were “afraid to stop gesturing” — even though “very seldom do you find a really great stage actor” who moves that way. Their motions are limited, precise. As he put it:

You watch Laurence Olivier on stage, and it's absolutely magic. The gestures are minimal. And this is what Bobo Cannon was able to do on film.

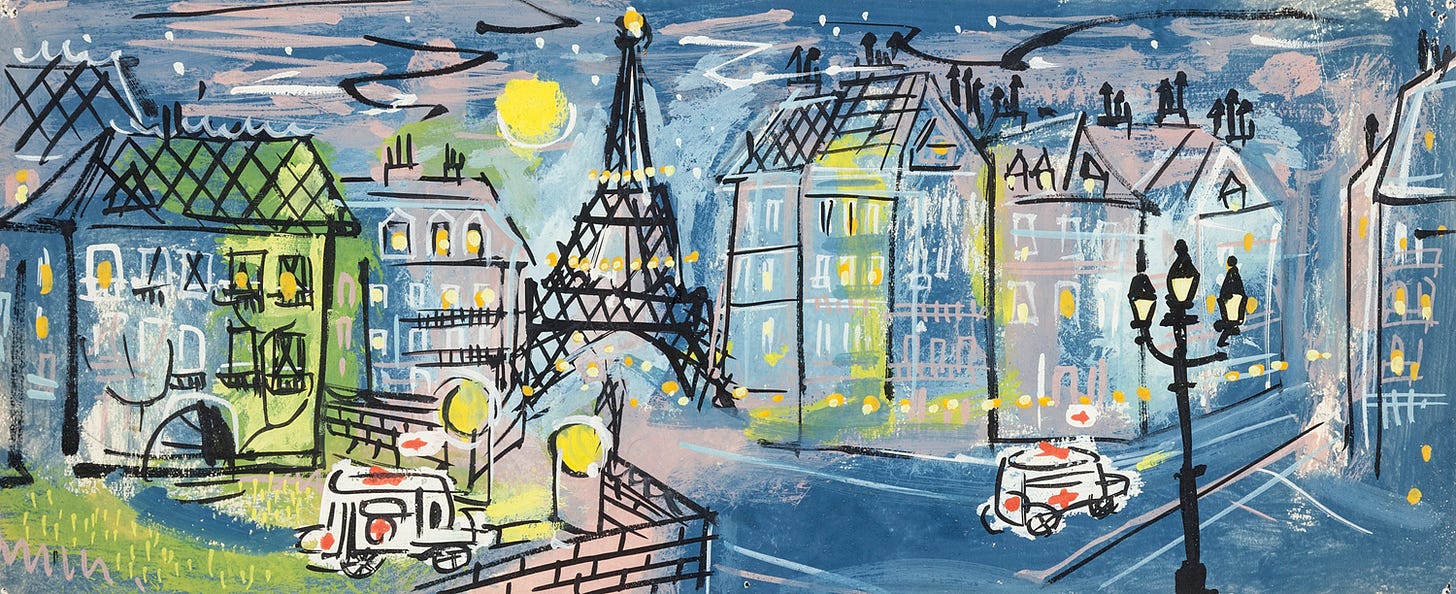

Madeline’s backgrounds were another issue. Abraham writes that Engel “clipped Bemelmans’ pictures and pinned them up for reference.” Yet the story goes that the book didn’t offer enough material to the artists. And so UPA filled in the gaps by drawing directly from Bemelmans’ own influence — the French painter Raoul Dufy.

By some magic trick, the flat-colored characters fit like a glove inside the detailed backgrounds. This was common in UPA cartoons. Engel once said that “the character was never in front of the background. The character was always in the background.” At the time, most studios left the distinction clear — which would have doomed Madeline.

Narrating it all is character actress Gladys Holland. She’d stopped by UPA during production and fallen in love with Madeline’s storyboard. Holland read it aloud out of curiosity — and landed the job. When she watched the following Oscars, she was surprised to see the film among the nominees. The Tom and Jerry cartoon that beat Madeline won her ire for years. (Later, she came to love that short, too.)

After Madeline, several more Oscar nominees would come from Cannon’s hand at UPA. When he left in 1957, it was “to found a new animation company with Ludwig Bemelmans,” Abraham writes. That studio never released a film, but you wonder what might have been. The two artists were at the height of their powers, and Cannon had a masterful grasp of Bemelmans’ style.

Either way, Cannon’s Madeline remains a little masterpiece. It might be the best adaptation of its source material ever made. Watching it today, it still feels fresh and vibrant — a testament to the talents of its whole team.

2. Headlines around the world

A big week in India

A lot happened in Indian animation over the last week. For starters, ASIFA India revealed its winners on Wednesday. Bombay Rose and an intriguing film called Wade nabbed Best Animated Feature and Best Animated Short, respectively. And Vaibhav Studios, the indie firm behind Lamput, won yet another award for its wildly creative Nickelodeon ident series. (See a few of them here, here and here.)

Meanwhile, Cartoon Network India unveiled its first CGI original, Ekans. It’s part of Warner’s continued investment in India — other recent examples include Debangg: The Animated Series from back in May.

And then there’s the odd one. Xentrix Studios is an Indian company known for outsource animation on shows like Ninjago and Kamp Koral — and it just bought the Australian animation house Viskatoons. The goal, Kidscreen reports, is to grow Xentrix out of the outsource market and into original projects. NFTs seem to be involved, for some reason. We’ll see what happens.

BUSINESS: Breaking down Japan’s anime boom

This week, Japan’s respected Animation Business Journal posted two interesting articles about the state of the anime industry. The first covers the government’s latest update on 2019 export sales. The second analyzes the explosion of streaming in Japan during 2020.

Anime was far and away Japan’s chief broadcast media export in 2019 — accounting for 85% of sales, or around $400 million. Japan tends to be cagey about how much the anime industry relies on Chinese money, but this report clarifies it somewhat. In 2019, Asia made up $224.6 million of anime export sales, compared to North America’s $102.8 million. The two largest importers were China and the United States.

As for streaming, it saw an explosive 65.3% increase in Japan during 2020, dwarfing 2019’s number. Given the COVID-19 pandemic, that makes sense. Foreign films took up the largest share among streaming users, but Japanese anime had the edge in overall viewing time. Both rentals and home video purchases continued their steady decline — for the first time, their combined revenue fell below that of streaming.

BUSINESS: What happened at Russia’s Key Buyers Event

The Key Buyers Event took place in Russia earlier this month. Organized by the government, it’s part of the country’s ongoing attempt to push itself into the center of global media. In plain language, it’s meant to hook Russian film and TV productions up with foreign partners, and vice versa. That includes animation.

This week, a flurry of news stories continued to piece together what happened at the event — and Izvestia brought the biggest. One highlight is Soyuzmultfilm’s blitz of distribution deals in France, Britain and Asia. There’s also 100 KiloWatt, which is still negotiating with foreign distributors. And the Riki Group landed another batch of global deals in Taiwan, the Philippines and America.

The Riki Group is worth pausing on. It’s a conglomerate with its hands in animation, video games and merchandise, and it’s quickly growing beyond Russia. Riki owns two animation firms — Petersburg Animation Studio and the recently-acquired Aeroplane. It’s a major force in Russian cartoons via series like Kikoriki, BabyRiki and The Fixies, all of which had their international English rights snapped up at the Key Buyers Event.

Overall, this thing seems to have succeeded. Considering how heavily the government is investing in media, that checks out. As Variety noted earlier this month, Russia has gone as far as “launching a cash rebate of up to 40% to lure foreign shoots to the country, while also introducing a fund to support Russian minority co-productions.” It’s a clear political power play, but it seems to be working.

Best of the rest

Netflix and Triggerfish, the premier animation studio in South Africa, announced a “pan-African Story Artist Lab.”

The French documentary Satoshi Kon, the Illusionist will debut at Cannes in July, and will stream at the virtual Fantasia Film Festival in Canada during August. As we’ve written, it contains footage from the late master’s unmade final film.

News broke Tuesday that Theodore Ushev, Canadian director of The Physics of Sorrow, is making two new films with the help of Miyu Productions in France.

One more from France — Cyber Group Studios announced a deal to create an animated series based on the video game Final Fantasy IX. Why now, 21 years later? Yahoo! Japan has thoughts.

Meanwhile, Yahoo! Japan also reports that Kōchi Prefecture is getting its first animation studio. Unusual, as around 90% of Japan’s animation industry resides in Tokyo.

In South Korea, animation is an outsource industry. Studio Mir (Voltron, Dota) is moving beyond those confines with a plan to go public and develop its own IP.

Another related to South Korea — the company Naver, which owns Webtoon, bought Wattpad last month. Both companies had studio divisions, and now Naver is merging them. A big deal, given how popular Webtoon anime already is.

Wolfwalkers will debut in China on July 3, the website ACGjie.com reported. Cartoon Saloon has a Chinese following thanks partly to Puffin Rock, a hit in the country.

The studio Myrkott, from Saudi Arabia, landed a coup when its film Masameer hit Netflix last year. Now an eight-episode Masameer series is coming to the platform on July 1.

3. Treasure trove — Koji Yamamura

Japanese animation has always been larger than one style. What’s considered the “typical” anime look changes with time. But the independent scene pushes things even further — and that’s where you’ll find the one-of-a-kind animator Koji Yamamura. There hasn’t been a better moment to watch his work, either, because he’s uploading much of it to his YouTube channel in restored quality.

If you’re new to Yamamura and his strange films, the best place to start is the Oscar-nominated Mt. Head. It adapts an ancient rakugo tale about the misadventures of man with a tree on his head. And don’t miss Yamamura’s children’s projects, like the mixed-media Karo and Piyobupt series or the one he made with the help of school kids.

That’s only the start. Yamamura’s channel is full of twists and turns from his 40 years in animation. There’s Anthology with Cranes, based on a scroll painting — right beside the funny and endlessly imaginative Notes on Monstropedia. There’s the surreal Perspectivenbox, the quiet Kipling Jr. and more. This channel is already a goldmine, and Yamamura updates it regularly. It’s a must for fans of out-there animation.

4. Retro ad of the week

Tex Avery helped to define Bugs Bunny, Elmer Fudd and other cartoon stars. He oversaw films like Red Hot Riding Hood and Symphony in Slang. But Hollywood and its pressures and predatory contracts finally got to him. In August 1954, Avery dropped out.

It wasn’t long before he found himself doing animated TV commercials. Advertising was a whole different world. For one thing, turnaround was fast — a relief for Avery. He once said that “you make ‘em in two weeks and you're through!” For another, TV animation was still an open frontier. Innovators like John Hubley were running wild.

The Yellow Went was the first product of Avery’s new career, he recalled. It’s a Pepsodent toothpaste spot from 1956 — and one of the first TV ads aimed at teens, per historian Lincoln Diamant. In it, a girl draws admirers with her teeth. “You’ll wonder where the yellow went when you brush your teeth with Pepsodent,” the catchy refrain goes. The commercial also hypes up an ingredient called “irium,” which doesn’t exist.

Avery based The Yellow Went on a hit radio spot. This was common — ad men often designed audio to be transposable between radio and TV. The Pepsodent jingle entered pop culture and shifted toothpaste advertising “away from the medical and back to the cosmetics approach,” per Sponsor. Avery’s visuals made an impact, too.

Avery was known for rapid-fire cartoons — he’d learned that “the eye can register an action in five frames of film” during his time at MGM, he said. That thinking informs The Yellow Went. Its transitions are quick, even relentless, compared to many ads of the day. Diamant argued that it “moved the theory of TV visuals forward,” paving the way for the “flickering, spastic 30- and 20-second spots” of the future. See for yourself:

5. Last word

And that’s the end of our newsletter this week! Thanks for reading.

One more thing. After Substack interviewed us last week, it seems we made a brief cameo on television. It happened when the CEO of Substack chatted with Bloomberg TV — a list of Substack’s author interviews appeared, and ours was at the top. A huge thank-you to Bailey Richardson, the site’s head of community, for sending us the clip (seen at 0:37). And thanks to Bloomberg for featuring us, even if only by coincidence.

Hope to see you again soon!