Two Artists, Linked Across Distance

Plus: news.

Welcome! It’s another Sunday issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s what we’re doing today:

1) Black Soul, and the friendship between two animators.

2) Animation newsbits.

With that, let’s go!

1 – Studying abroad

A video blew up this week. It’s a clip from Black Soul, a Canadian film released 25 years ago. We posted it on social media — and the musician Aïsha Vertus shared it. “That’s my auntie who made this film,” she wrote. “She’s a genius!”

The clip reached hundreds of thousands of people from there.

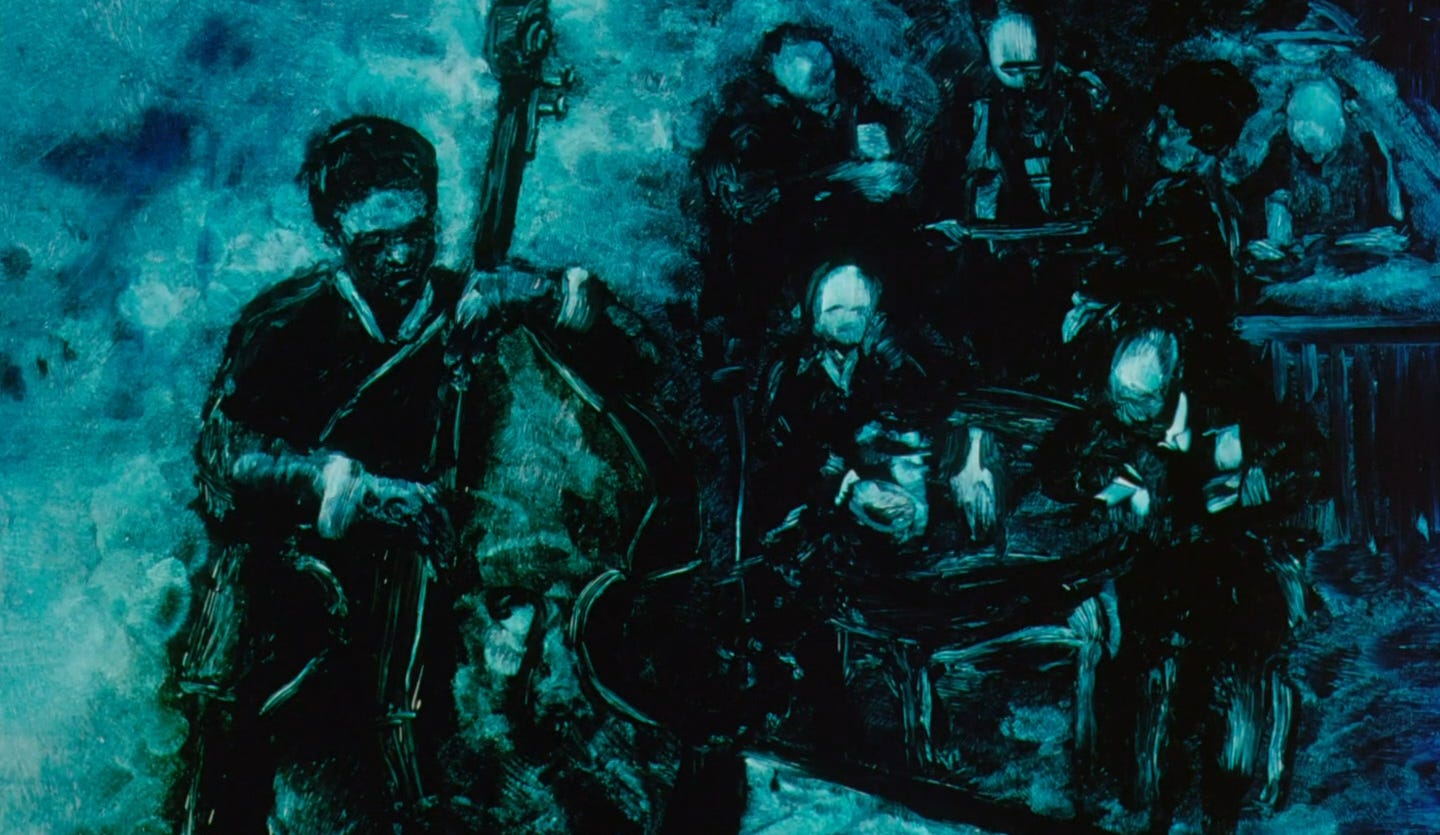

It was surprising. Black Soul is a beautiful film, but it’s not flashy in the way that tends to get attention on social media. It’s a trip through history — a kaleidoscopic one that morphs from scene to scene. The film’s director called it “a wordless tribute that traces the history of Black people, from the beginning up to the present.”1

That director’s name is Martine Chartrand, and she animated Black Soul with oil paint on glass. Creating it took seven years, including roughly “five-and-a-half years of animation,” she’s said. Chartrand painted it mostly with her fingers, using the less toxic oils produced by Holbein and Rembrandt. At times, she found herself in her dimly lit workspace “seven days a week.”2

Once finished, the film quickly turned into a big deal — it even won a Golden Bear in Berlin.3 No Canadian short had taken that prize since the ‘80s.

For Chartrand, the project was the fulfillment of a dream. A key part of this dream was the technique she used. In the early ‘90s, she’d been changed by an encounter with the painted animation of Alexander Petrov. The two artists lived in separate worlds — Petrov worked in the USSR at the time. But Chartrand decided that, somehow, she would become his student.

And she did.

When Alexander Petrov rose in the ‘80s, paint-on-glass animation wasn’t new. It’d appeared in films like Horse from Poland and The Street by Caroline Leaf, made during the ‘60s and ‘70s. Artists in Germany had used it as early as 1921.4

But Petrov’s approach was fresh. His first painted masterpiece was The Cow (watch), a student project from ‘89. It was something remarkable. When it screened at a Canadian festival the following year, it stunned Chartrand. She recalled:

I was completely bowled over. I really liked the work of Caroline Leaf and Wendy Tilby, but when I saw the work of Alexander Petrov... I have a great love for Michelangelo and Rembrandt, and I truly felt like I was seeing an animated Rembrandt. I remember I was with Pascal Blais, a good friend, and I told him, “I think I’m going to go study with him.” He didn’t really believe me. So I kept it a secret. I told myself, “Well, I’ll learn Russian.” … For four years, I studied Russian without fully knowing if I was going to travel to Russia.

When Chartrand caught The Cow, she was working as an animation artist at Canada’s National Film Board. Eventually, she became a director there with the hand-drawn TV Tango (1992). But learning Petrov’s method was, again, her dream.5

She mailed him letters for a couple of years, trying to organize a trip, without really hearing back.6 Chartrand had never seen a picture of Petrov and (based on his work) assumed he was a veteran. “I thought Petrov was an old man,” she admitted. And she worried that time was running out to study under him.

In ‘93, Chartrand brought the plan for Black Soul to the National Film Board. The project required more than a year of research into the slave trade and Canada’s part in it. As she prepared, she happened to ask a high school class in Montreal for feedback — including how the students wanted to be represented in animation. “Make us beautiful and proud,” one of them replied. It set her course.7

She decided to experiment with paint on glass for Black Soul. For that, Chartrand felt she needed to meet Petrov. Ultimately, she reached him through his producers and got a green light to visit — plus Canadian grants to do so.8 In 1994, even as many warned against the idea, she flew to Russia.

For Alexander Petrov, much had changed since The Cow’s release.

His film traveled the world. It brought him a bit of a name, and the first Oscar nomination for a Soviet animated film. Then he followed it with The Dream of a Ridiculous Man (1992), another gem, likewise painted on glass. But, more and more, he was struggling.

To start, The Cow’s defeat at the Oscars crushed him for a while. “It seemed to me that everything had collapsed, almost to the point that I needed to change my profession,” he recalled. And Ridiculous Man was a project carried out “painfully and with difficulty, always at the edge of failure, at the edge of despair.”9

Meanwhile, the USSR collapsed in late 1991. Amid the upheaval, Petrov and his family moved back to his birthplace, the Yaroslavl region, to start a new animation studio. He ended up stranded there with “no place to work, no money to make a film, no materials, no equipment.”10

As Chartrand’s letters arrived in the mail, Petrov was trying to set up a functional camera in Yaroslavl — scammers from Moscow had sold him one without a motor. He ignored her. “I didn’t treat it seriously; I thought it was some kind of whim, nothing more,” he said later. What was there to see in his non-existent studio, anyway?

Yet Chartrand kept trying. And, once the camera was working again, Petrov gave in.

Neither of them knew what to expect. They’d faxed back and forth, but Chartrand still hadn’t seen a photo of Petrov — she thought of him as “an old man with a long beard.” She hadn’t mailed a recent photo of herself, either. Chartrand was 32, but Petrov believed she was 10 years younger, based on an old TV interview she’d sent him.11

She was nervous as she stepped off the plane; her guard was up. Petrov recounted their first meeting. “I approached, nearly [her] same age, and introduced myself as Petrov,” he said. “She was completely terrified, thinking that they’d started to dupe her the moment she entered the country.”

By then, Chartrand spoke a little Russian, and Petrov spoke a little French. It was awkward initially. “During our first conversation, she immediately started... swearing!” Petrov remembered. As they traveled to Yaroslavl by train, he made small talk: “I decided to inquire [in French] if my guest liked to fish,” he said. But the word for fishing (pêche) came out sounding like “sin” (péché).

The misunderstandings faded away, though. Living with Petrov’s family, Chartrand found a new home.

When Chartrand entered Petrov’s studio in Yaroslavl, his working conditions were maybe the humblest of his career. His equipment sat in a room of only 150 square feet — and the equipment itself came from wherever he could get it.12

“I remember well that, when I arrived, I was very struck by the tables on which my teacher worked,” Chartrand said. “They were so rickety, they were practically shaking.”

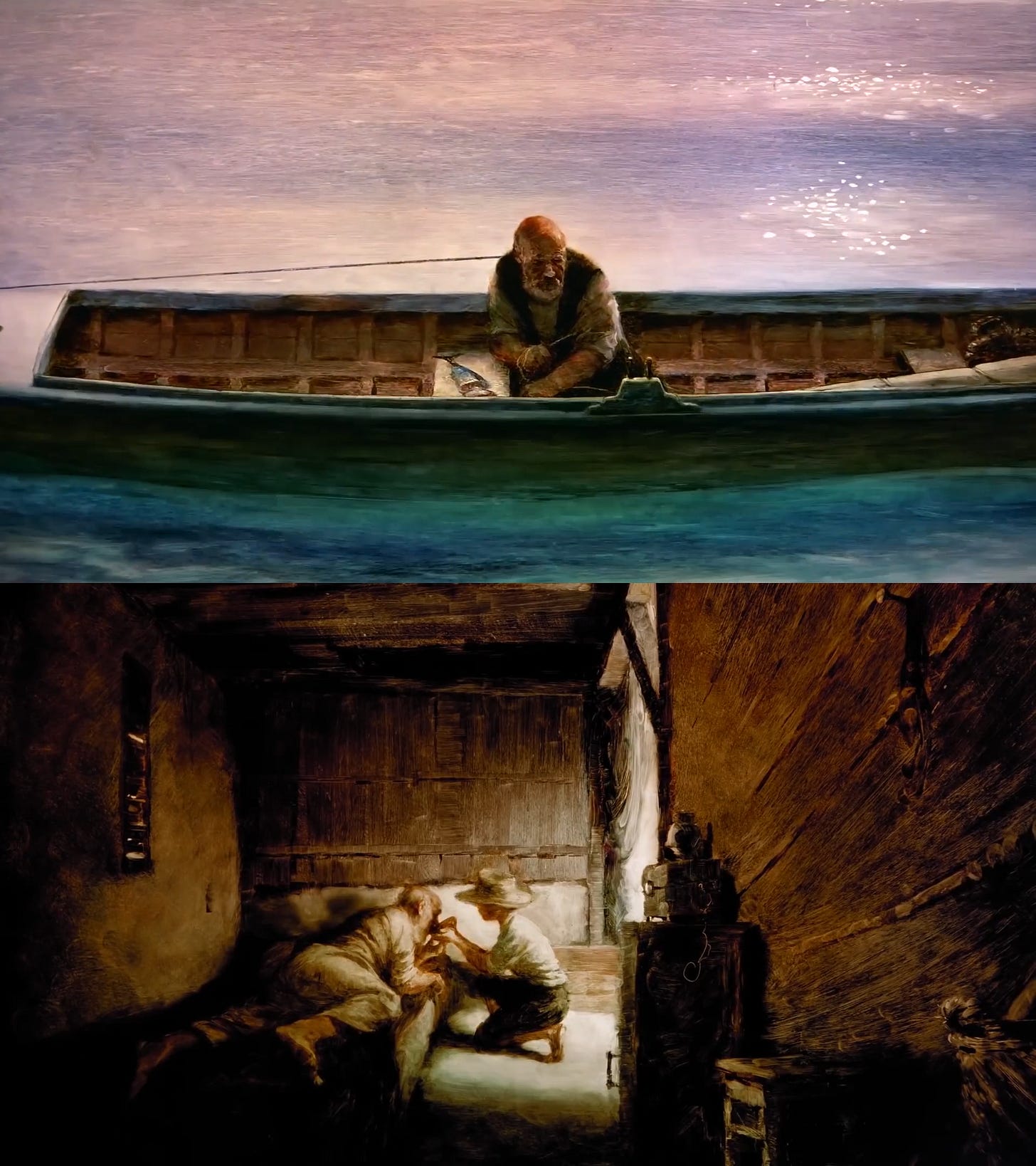

She regularly came into the studio to work during her stay, just as Petrov did. Chartrand was developing the storyboard for Black Soul at the time — this exploration of Black history, and how it passes from an old woman to a young boy. Petrov was about to make The Mermaid (1996), based on an old Russian story.

“I mainly learned to work alone, because Alexander was sitting at his table and I was working under the camera,” Chartrand recalled. “Occasionally he would come to see what I was doing. I was like an apprentice.”

Petrov was a low-key, hands-off teacher. But he still revealed things to Chartrand. “From Petrov, I learned to question my animation,” she said. Every shot needed to be analyzed and every unnecessary detail needed to be removed. And it was Petrov who persuaded her to make Black Soul a fully painted film — much more than the “bit of painting on glass” that she’d originally planned to use.13

Critically, Chartrand also came to understand the need to be her own artist. As she said:

At one point, I was working by myself, and it occurred to me, “To think that I came here from so far away, and I’m working all alone.” So I asked Alexander to work on a scene with me, each of us handling one of the characters: he did the old woman and I did the boy. The two of us, side by side and really close together, were working at the same time. So, I could truly see how he worked, and he could see how I worked. But he didn’t correct me because what he wanted was for me to develop my own style. Because it’s impossible to be like Alexander. He’s a hyper-realist; I’m more impressionistic.

While in Yaroslavl, Chartrand fit into Petrov’s circle — her stay of one month grew into three months. “She made many friends; everyone loved her very much,” Petrov said.

One of these new friends was Petrov himself. They got along. At one point, he showed her a script and sketches for a project he’d considered since the early ‘80s. It was an animated version of a Hemingway book: The Old Man and the Sea. The idea excited Chartrand, who felt that producers in Canada might accept it. “I brushed it off,” Petrov noted.

It turned out, though, that she was right.14

After a tearful departure, Chartrand went back to Montreal. Within a couple of months, she had Canadian studios interested in Petrov’s idea.

He and his family flew to Canada in the mid-1990s. There were many meetings about The Old Man and the Sea, all instigated by Chartrand. As Petrov said:

She invested a lot of time, effort and resources to ensure that I came to Canada, and that I gave a good presentation of my project. She translated the texts I wrote there into the French language. She did tremendous work, and with her help we realized this project.

It didn’t happen overnight. Petrov’s first talks in Canada were inconclusive, and he went back to Russia to finish The Mermaid. Eventually, though, The Old Man and the Sea got made. Petrov lived in Canada for a few years to do it.

Chartrand was creating Black Soul at the same time. She spent long years alone in the dark — with her fingers in the paint, like Petrov. To slow its drying as she animated, she mixed bicycle grease into it. Chartrand shot some 14,000 frames of Black Soul but was ruthless in the editing stage: around half were cut, which isn’t something done lightly. “Five seconds is three centuries,” she noted.15

The Old Man and the Sea came out in 1999. It made Petrov famous — and it finally won him an Oscar, which allowed him to start a real studio in Yaroslavl. Black Soul landed the following year and announced a major new name in painted animation, with her own style. It took, as mentioned, the prestigious Golden Bear.

The two films were deeply linked, as were their creators. After all, Petrov had inspired Chartrand to make Black Soul into a paint-on-glass film. And he credited the existence of The Old Man and the Sea to her. “Martina plays a substantial role in my fate,” he once said. “The film The Old Man and the Sea, and my work in Canada, and all my subsequent achievements — all are tied to her involvement.”16

They stayed good friends. Chartrand visited Yaroslavl in 2013 to show Black Soul and her painted film MacPherson (2012); the local news covered it.17 In 2019, Petrov said that Chartrand had become “like a sister” to him.

Seeing The Cow in the ‘90s had changed Chartrand, but her effect on its creator was at least as large, if not larger. Her decision to take that trip to apprentice under him — which almost no one took seriously, including him — ended up elevating her career and his. The two artists came from separate worlds, but she insisted on building a bridge. In her beautiful art and his, we see it at work.

2 – Newsbits

We lost Tony Benedict (89), a veteran of Hanna-Barbera and UPA.

In Czechia, a stop-motion feature has been restored: Adventures of Sinbad the Sailor (1974) by Karel Zeman. It hit theaters this month. See a trailer here.

Maybe the most unsettling animation news of the week came from America, where Netflix announced a deal to buy Warner. The ink isn’t yet dry, but Ted Sarandos is already talking about shorter theatrical releases.

In China, Zootopia 2 continues to make Nezha money. It just passed $430 million and could become the biggest foreign film released in the country, beating the fourth Avengers.

India’s Vaibhav More did some intriguing stop-motion animation for a recent commercial.

Check out the pilot trailer for Where Did It Go Wrong? — a Hungarian film years in the making, whose director still intends to get it done.

The French director Rémi Chayé is continuing to pursue his feature Fleur, and Eurimages just gave the project €500,000. You might know his films Long Way North and Calamity.

As media control increases in Russia, a new document is being prepared to outline, in detail, what it means to create work that follows traditional “moral and spiritual values,” as required by the state.

Also in Russia: Tied Up, the latest feature from Oscar nominee Konstantin Bronzit, was a serious flop.

Last of all: we published an on-the-ground report from Beijing, where a major exhibition about Shanghai Animation Film Studio took place.

Until next time!

See Cap-aux-Diamants (Autumn 2004), used a lot today.

Details from Playback, The Animation Bible and Chartrand’s interview in the book Métier realisation. We used them all several times; the third was one of our most-cited sources today.

Her Golden Bear win is discussed in the book Animation for the People. The film had “formidable international prestige” by 2002, reported The Gazette (February 18, 2002).

Discussion of the paint-on-glass technique in the 1921 film Lichtspiel Opus I appears in A Reader in Animation Studies.

Petrov talked about the letters here and in an interview with Pravoslavie i Mir. Both were used a lot, and the second was a main source.

The quote and details about the students come from a 2022 paper by Chartrand. The ‘93 date originates from this blog post, used a few times. As a note, Chartrand’s deep exploration of Black history began with a Black History Month poster she created in 1993 — see it here.

Chartrand mentioned the grants on her archived personal site.

These quotes come from interviews with Cinema Art and Film Studies Notes.

For these details, see Petrov’s interviews with Izvestia and Mirror of the Week, both important today.

See this article from Cultural Evolution, used several times.

These quotes come from Fluid Frames and the MacPherson press kit.

Chartrand discussed editing Black Soul in this TV interview and the foregoing sources.

This has to be one of the greatest stories on networking that I’ve ever read! And for such a laborious yet gorgeous branch of animation! It’s truly inspiring!

What a story! I feel such stories can’t occur but in Russia!

And oh Petrov the genius artist i wish he make more and more films, each frame he draw is a masterpiece, the world would’ve been better if had the right finance, if he were able to make longer films, nevertheless he already made a beautiful world in his shorts!

And Chartrand you’ve done a very well job indeed!

Animation obsessive, do you think you’ll be able to interview the man himself? I wish you can.