Happy Easter, and welcome to this week’s edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter!

We’re starting with a dive into the importance of Three Monks, a classic piece of animation from Shanghai. It heralded a new age for cartoons in China — after years of brutal repression. Stick around for the week’s top animation news and a lookback at an outrageous claymation film from the USSR. It’s all down below.

For those new to our newsletter, we do this every week — and you’ll never miss an issue if you sign up for free:

With that out of the way, let’s get into it!

Three Monks, a rebirth for the Chinese cartoon

In the discourse about animation, we’re often stuck on America, Europe and Japan. You’d never know what riches a country like India has given to the artform, and that’s a shame.

The most unfairly overlooked cartoon tradition, though, might come from Shanghai Animation Film Studio. State-funded but too creative to stay a simple propaganda outlet, it spent decades as the center of animation in China. Along the way, it spearheaded two golden ages for Chinese cartoons.

The first one, from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s, turned the medium on its head. It invented ink-wash animation and produced the sweeping epic Uproar in Heaven. The second golden age started around 1978, and its spirit is best represented by a little film called Three Monks.

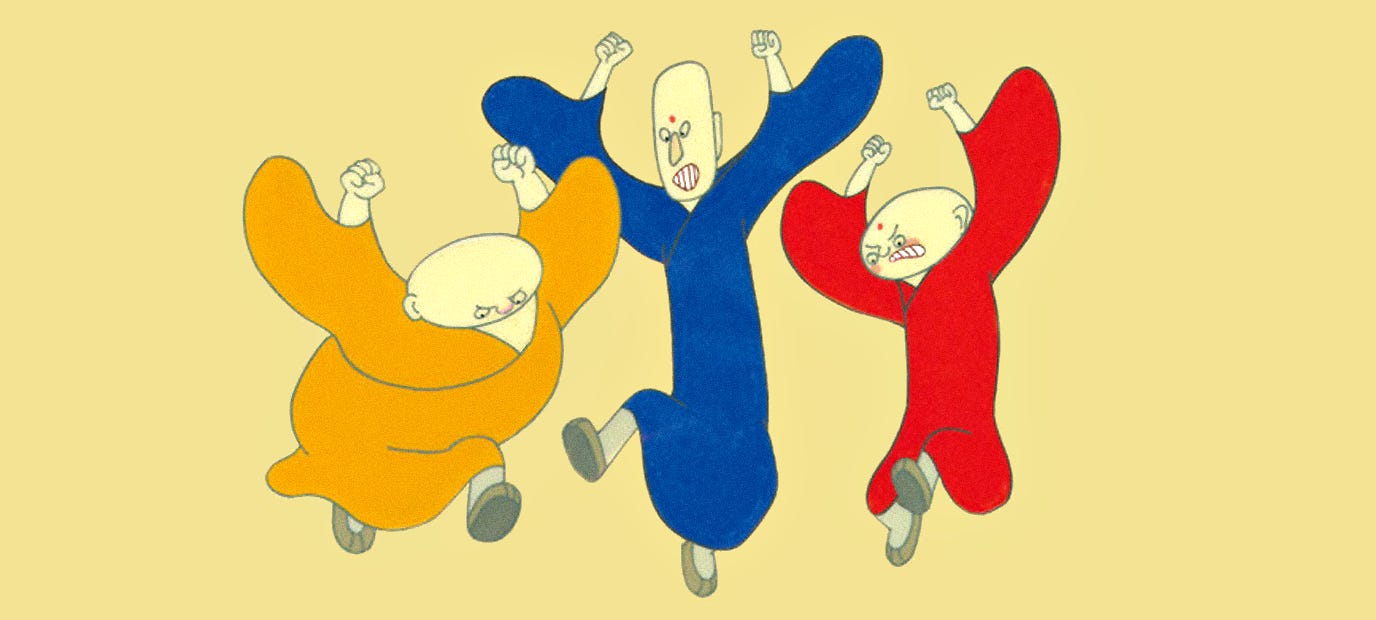

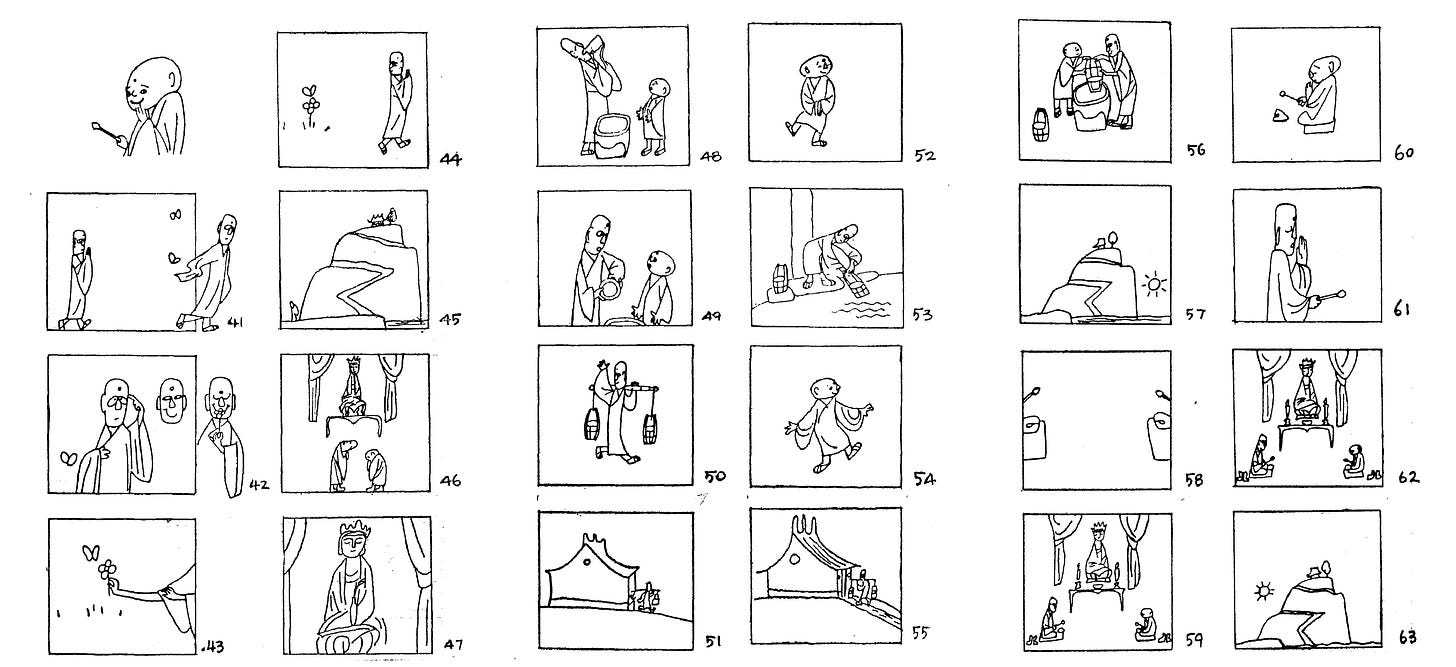

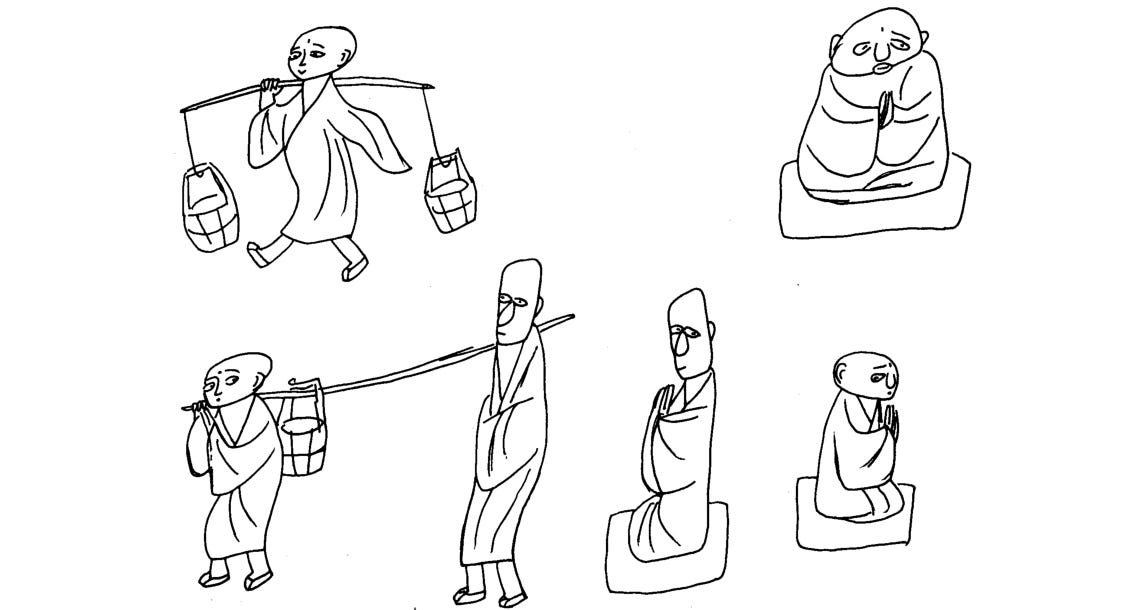

Three Monks is an exercise in beautiful, deceptive simplicity. It has no dialogue. The character designs are stripped back — and the backgrounds are spare when they’re present at all. But director A Da, born Xu Jingda, assembles these pieces into a modest masterpiece. The team took a basic style and tried “to make it as perfect as possible,” the director later said.

The film is an animated retelling of a Chinese proverb. Rendered in English, it says that “one monk will carry two buckets of water; two monks, one bucket of water; three monks, no water at all.” Essentially, more people achieve less. Three Monks spends around 20 minutes infusing these words with warmth and humor, through a trio of characters as alive and human as any you’ll find in animation.

A Da subtly subverts the original proverb, though — and flips his film into a radical statement of protest. To Chinese audiences at the time, Three Monks was a clear plea for peace and unity, in the face of violence that the director and his co-workers had seen firsthand.

Animators aren’t strangers to government persecution. Russia may celebrate Andrei Khrzhanovsky as an icon now, but Soviet leadership forced him to serve two years in the military for a political faux pas. The House Un-American Activities Committee pummeled UPA and had John Hubley blacklisted from Hollywood. Even then, very few animators have encountered anything like the Cultural Revolution.

By the mid-1960s, the first golden age of Chinese animation had come to a screeching halt. Shanghai Animation was “all but closed down by the Red Guards of the Cultural Revolution from 1965 until 1972,” David Ehrlich wrote in the book Animation in Asia and the Pacific.

The unluckier Shanghai Animation staff were tortured, including its star director Te Wei. He later recounted beatings, days without sleep and a year in solitary confinement. A Da was luckier. As part of a “re-education” program, he was forced to work as a farmhand and write self-criticism — disowning his countless alleged crimes. Per Ehrlich:

For three years, A Da fed hundreds of pigs and dug septic canals. Forbidden even to do sketches, A Da nevertheless hid under his mosquito net at night to draw from his memory and imagination unflattering caricatures of the Gang of Four whom he held responsible for the chaos in China.

Chinese animation, like China itself, was devastated by its last years under Mao and the Gang of Four. The Cultural Revolution tore China in half, pitting young against old, student against teacher, child against parent. Even traditions as old as China itself could be deemed subversive and criminal. When animation became useful again, it was only as sterile propaganda.

“In 1972 we were sent back to Shanghai, to make propaganda films,” A Da later told the Los Angeles Times. “That was better, because I could rejoin my family. But the films were very bad … there was no art in them.”

In 1976, the Cultural Revolution collapsed with the death of Mao and the arrest of the Gang of Four. The fear and tension that had gripped Shanghai Animation during its propaganda years slowly dissipated. “We could even begin to dance again at that time,” animator Lin Wenxiao recalled.

Soon, A Da and Wenxiao co-directed a satire called One Night in an Art Gallery. Released in 1978 to public acclaim, it mocks the Gang of Four through the caricatures that A Da had learned to draw in his years as a pig-feeder. “When we began this film,” Wenxiao remarked, “we were not afraid.”

The idea for Three Monks arrived the following year, in 1979. A Da had a run-in with the monk proverb at an event held by the Ministry of Culture, and a film began to take shape. It would grow into a “way of communicating the idea that we need to work together to reconstruct our country,” as A Da later put it.

Cartoonist Han Yu came aboard to design the characters in his signature loose, freehand style. Meanwhile, A Da storyboarded the film by himself and choreographed each moment to fit the pre-recorded score, done in a traditional style. The master animator Ma Kexuan played a core role as well, drawing long sections of the film and polishing A Da’s choreography.

Fully assembled, Three Monks symbolized a new dawn for Chinese animation. It’s wholly free from the aesthetics of the Cultural Revolution — it draws on Western art and traditional Chinese culture in equal measure. The film became A Da’s crowning achievement, and one of China’s most celebrated cartoons at home and abroad. It won the first of China’s prestigious, state-run Golden Rooster awards for animation.

But Three Monks’ message, its subversion of the original proverb, remains the most important piece of its puzzle.

Near the end, the three monks are left without water. They’ve grown bitterly divided. And then a crisis erupts — their temple catches fire. In the moment, they choose to settle their differences to save their home, working together to carry water up from the lake. They extinguish the fire, and close out the film united as friends.

“It was … A Da’s special cry that the split in China caused by the Cultural Revolution, the split that turned one family member against another,” Ehrlich wrote, “would result only in destruction and should never be repeated.”

Headlines of the week

Annecy 2021 gears up

Annecy, one of the world’s most important animation festivals, on Tuesday revealed this year’s slate of competitors.

The official list packs over 100 film and TV projects from around the world. It also “gives pride of place to African animation with works from South Africa, Ghana, Egypt and Kenya,” according to the event’s art director Marcel Jean.

Annecy was held online last year because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but this year will take place in a “hybrid virtual/physical” format, Animation World Network reports. We’ll be following the festival as it unfolds.

Junk Head‘s success in Japan continues

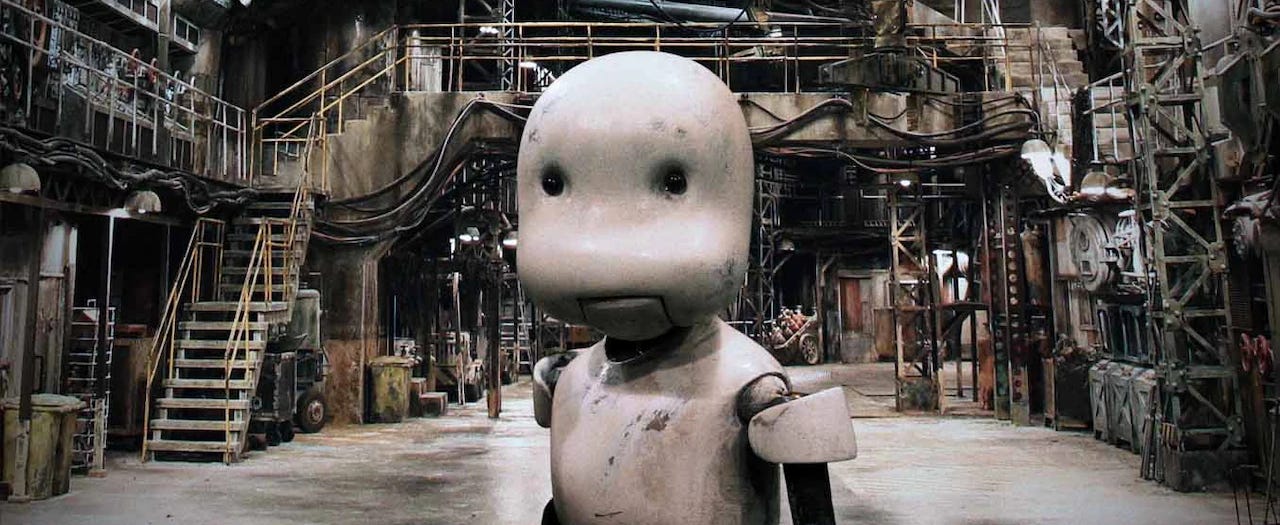

After a strong performance in Japan’s independent “mini theaters,” Junk Head spread to mainstream theaters in Tokyo and beyond this week, the Japanese film site Natalie reports. The outlet also shared an intriguing timelapse video from the film’s creation.

Junk Head is a hyper-ambitious stop-motion film set in a dystopian future. A virus has devastated humanity, but a vast, twisted society survives underground. The protagonist stumbles across it while badly damaged, and the locals rebuild him out of junk. That’s the start of his truly phantasmagoric journey.

It’s hard not to be inspired by the story behind Junk Head. Director Takahide Hori crafted it over a period of seven years — overseeing nearly every aspect of its production. He taught himself the process along the way, inspired by Makoto Shinkai’s period as a solo filmmaker, per Natalie. Junk Head has since been praised by Japanese luminaries like Hideo Kojima.

Mamoru Hosoda’s Belle attracts international talent

New information continues to trickle out about Belle, the next feature by Mamoru Hosoda (Mirai, Summer Wars). This week, its official trailer debuted — and Hosoda’s Studio Chizu revealed a number of international collaborators for the film.

Jin Kim, a Disney veteran known for his work on projects like Zootopia and Frozen, is attached as a character designer. And the directing duo behind Wolfwalkers, Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart, have provided their own sequence. On Twitter, Moore offered a bit of insight into Cartoon Saloon’s involvement:

We’ll look forward to seeing what Ireland’s top animators have cooked up for Belle. Meanwhile, if you’d like to read more about Hosoda’s new film, Variety has the story.

From the vault — Gray Wolf and Little Red Riding Hood

In response to last week’s issue, a reader under the handle “nyy” asked us to write about the films of Garri Bardin, a stop-motion master who got his start in Soviet Russia. By coincidence, one of the Bardin projects nyy suggested is one of our very favorite Russian cartoons — Gray Wolf and Little Red Riding Hood. So, here we are.

There are hundreds of odd spins on Little Red Riding Hood, but you’d be hard-pressed to find one odder than Bardin’s. Gray Wolf is a surreal musical in clay, and, well before it ends, the Wolf has already sung a rendition of “Mack the Knife” and eaten Disney’s Seven Dwarfs. He’s also a biting parody of the Soviet Union itself.

Released in 1990, Bardin’s comedy came at the end of the USSR, as the system was crumbling. Like Three Monks, it’s a film on the border between political paradigms. The difference is that Gray Wolf is an outrageous, take-no-prisoners assault on the same regime it was made under. This is one of the most politically incendiary Soviet cartoons of all time — it simply wouldn’t have come out even eight years before.

The Wolf starts the film toothless and starving, defanged as punishment for his crimes. He makes himself out to be a victim, though, and cons his way into a pair of steel dentures from Doctor Aybolit, a Russian children’s book character similar to Doctor Dolittle. Naturally, the Wolf devours him. He later feasts on the Three Little Pigs and the iconic Russian characters Cheburashka and Gena the Crocodile.

All the while, Red Riding Hood tries to deliver a pie to her grandmother in Paris — knocking over trees and, in one of the film’s best sequences, surviving a dance with the Wolf himself. Somehow, it all culminates in a mass uprising against the Wolf from inside his own stomach.

It all works even if you don’t know Russian history. The gags land on their own merits, from the Wolf’s stretchy leg in Aybolit’s office to Red Riding Hood’s twirl into the dirt. The clay animation and especially the camerawork are wildly inventive — even newer clay films rarely make the camera feel so physically present in the scene. The weird perspectives and occasional fisheye lens feel influenced by Brazil and other then-new Terry Gilliam projects.

We’re only aware of one English version of Gray Wolf and Little Red Riding Hood on YouTube, and it’s split into three parts. If you have 27 minutes, there are worse ways to spend it than by watching one of the finest and funniest claymation films ever made.

Last word

That’s all for this week! We hope you’ve enjoyed. Next Sunday, we’ll be back with more animation highlights from around the world.

In the meantime, you might consider another animation newsletter on Substack — Owen Dennis's Infinite Train of Thought. Dennis is the creator of Cartoon Network’s Infinity Train, and he uses Substack for irregular updates and behind-the-scenes from his career. It’s an interesting peek into America’s modern animation industry that’s worth a look.

Until next week!

"Grey Wolf & Little Red Riding Hood" can now be seen in its entirety with English or Spanish subtitles here:

https://www.animatsiya.net/film.php?filmid=445

(the video is from Soyuzmultfilm's official channel, with the subs overlayed on top)

Incidentally, many of Bardin's other films can be seen as well, including his 2010 animated feature:

https://www.animatsiya.net/director.php?directorid=14

(not all of them yet, more will be added, I hope. His most famous one in Russia remains "The Flying Ship" from way back in the 1970s!)

I think, personally, Bardin's films have great technique, humour, cleverness and even wisdom (as in "Adagio"). Yet, the theme that really inspires Bardin (most of his films seem to be variations on this) - and it is coated in all sorts of attractive packages, but it's not actually a super nice one at its core - seems to be that of seeing the mass of the people around as crude cattle, and the implications of this.

Interesting write-up on Three Monks. It's a pity Shanghai animation fell prey to the cultural revolution, especially since it's unlikely to ever recover from it. Uproar in Heaven is a testament to what Chinese animation could have been. Tremendously creative film. Asian aesthetics taking centerstage (e.g. woodblock prints, traditional guó huà) is a quality Japan's early output simply didn't have, at least not to this extent (e.g. Horus, Wanpaku, Hakujaden owe much more to western art and animation). However, what really elevates that film to a higher realm is the artistry of inking department (iirc the only anime film to ever notably distance itself from standardized black lines was Sirius no Densetsu) and it makes me wonder why Anime has yet to distance itself from standardized black oulines.