Why a Cartoon That Enraged Censors in the USSR Still Speaks to Us

Plus: classic Hubley animation and the week's top stories.

Welcome to another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter!

This week, we’re starting with a dive into Absent-Minded Giovanni, a charming short from the USSR. It went over well when we shared it on Twitter this week — and there’s quite a story behind it. After that, you’ll find the week’s top animation news and a double dose of Hubley animation.

If you’re new to the Animation Obsessive newsletter, we do this every Sunday. You can sign up to catch each new issue as it releases, for free:

With that said, let’s get into it!

‘I felt like a hero’

Earlier this week, we shared a clip from a Soviet-era Russian short called Absent-Minded Giovanni. The response on Twitter was very, very positive:

The main driver of attention toward Giovanni was pretty clear — a lot of people thought that it looked like Joel Guerra’s surrealist ENA cartoons. The series has been a hit since it kicked off in 2020, racking up millions of views per episode. More than a few people who saw our tweet believed that this Russian gem had inspired ENA.

The similarities are likely a happy accident. Guerra has cited Picasso and the contemporary artist Romero Britto as his influences. With ENA, he’s simply joined the rich lineage of cartoons based on modernist painting. Absent-Minded Giovanni was a trailblazer in this lane — beating the odds to create a world in which cartoons like ENA can exist freely.

Giovanni comes from the Moscow studio Soyuzmultfilm, from the hand of Anatoly Petrov. He was “the leader of the group of young [Russian] animators who so powerfully and dazzlingly declared themselves in the late 1960s,” per historian Georgy Borodin.

Petrov had started at Soyuzmultfilm in the late 1950s. Stalin was dead, but the studio still leaned on the realistic, rotoscope-heavy animation mandated in the Stalin era. “I wanted to move animation forward,” Petrov later said. He watched the aesthetic climate thaw in real time as an animator on The Story of a Crime, the 1962 film credited with bringing modern visuals and storytelling to Russian cartoons.

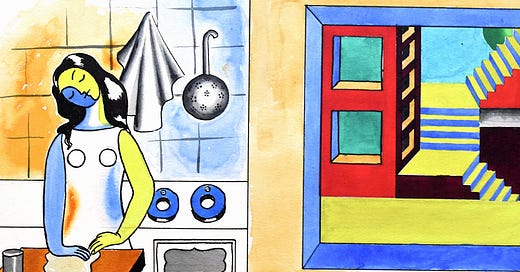

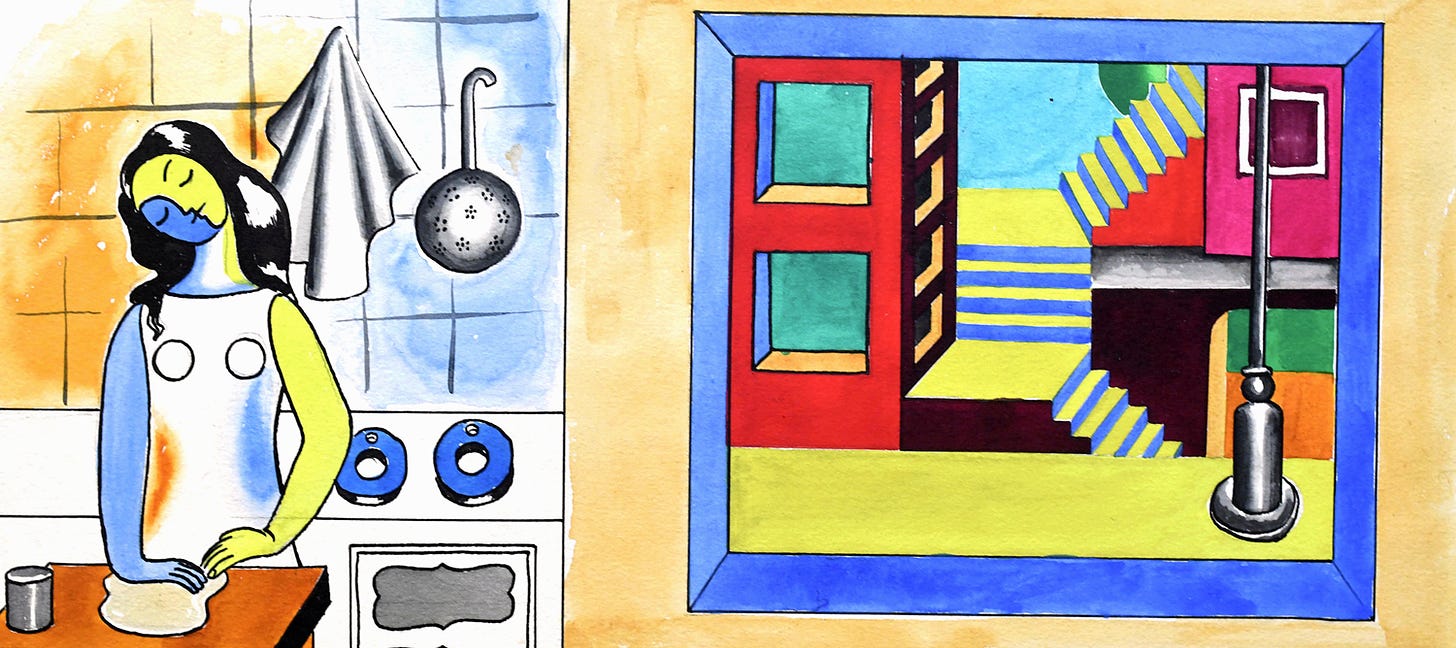

By the late ‘60s, Petrov had studied animation in Yugoslavia and was ready to make his own statement as a director. His debut Singing Teacher “immediately became one of the unspoken artistic manifestos of the Soyuzmultfilm youth,” according to Borodin. But Petrov pushed the envelope further with Absent-Minded Giovanni — his attempt to bring the modernist paintings of Fernand Léger to life and “master a new form,” as he put it.

Drawing from Léger made sense for an animator in Russia’s post-Stalin wave. Many of them learned about modern art in school. Petrov’s colleague and later wife, Galina Barinova, recalled that “they began to bring foreign painting to the USSR; we saw the works of Picasso and wanted to try something like that.” Petrov had already fallen in love with Léger’s art before he decided to adapt it.

The big question was how to make it move. It was a problem that dogged Petrov throughout his career, as he tried to turn still images into motion pictures.

“If you take from Picasso, then you must find a style of movement organic to the art of Picasso,” Petrov once said. “[And,] if you take from surrealism (Salvador Dalí, for example), then you must have a surrealist style of movement.”

Absent-Minded Giovanni doesn’t move like any other film of its era, or maybe any era. Characters’ shapes have the solidity of stop-motion, and yet they move across the screen in fluid, bouncy ways. The motion is “a little mechanical,” as Barinova put it, but it’s anything but stiff.

Clocking in under three minutes, Giovanni was Petrov’s contribution to the first episode of Happy Merry-Go-Round, a Russian cartoon anthology designed to give voice to new forms of animation. He and Barinova helped to start it in the late ‘60s, and it became a breeding ground for talent. Well, Just You Wait! would be Russia’s biggest cartoon — but its pilot first ran right alongside Giovanni.

Giovanni’s path to appearing on Happy Merry-Go-Round was a bumpy one, though.

Petrov came of age as an artist during the so-called “Khrushchev Thaw.” The political landscape was less inviting when he finally started directing. His colleague Andrei Khrzhanovsky was forced into the military, at the age of 29, over the government’s negative reaction to his 1968 film Glass Harmonica. While Giovanni lacks the radical politics of that film, its modernist aesthetic still disturbed the people in charge.

“When we created the first edition of Happy Merry-Go-Round, we were condemned at the plenum of filmmakers,” Barinova said.

Petrov recalled that the head of Goskino (the nickname for the State Committee for Cinematography) called out Absent-Minded Giovanni and Barinova’s Mosaic by name. The man remarked that “there were some attempts to use the platform of children's cinema as propaganda for abstract art.” In the subtle wording of a Soviet bureaucrat, this amounted to being named, as Petrov put it, “the enemies of Soviet cinema.”

“And I - I felt like a hero,” Petrov said. “Because, at the time, getting that kind of criticism meant that I was doing the right thing! The lecture was over, a break was announced and I walked out into the foyer so proud.”

Despite Goskino’s initial concerns, Absent-Minded Giovanni and the other films in the first Happy Merry-Go-Round made it to theaters mostly intact. The series has been running ever since — and it gave rise to some of Russia’s most visually adventurous directors. Petrov continued to get in trouble with the Soviet censors for much of his career, but stayed a leading light with films like Proving Ground.

As for Giovanni itself, this week seems to have proven that its modernist style can still wow audiences — more than half a century later.

Headlines of the week

Bilibili faces regulations on animation

Bilibili has become a major force in international media. The Shanghai-based platform, often called China’s YouTube, first rose to prominence in the local ACG (“Anime, Comics and Games”) subculture. But Bilibili had already grown to a reported value of $8 billion when Sony bought a stake in the company last April.

Even as Bilibili has shifted toward the mainstream, it hasn’t loosened its grip on China’s animation streaming market. It self-produces animation and remains its country’s premier service for Japanese anime, holding the exclusive rights in China for many series. Recent moves by the government have complicated that business model.

According to Yahoo Taiwan and Taiwan’s United Daily News, China has issued new restrictions on foreign animation, requiring it to pass official review boards. Bilibili’s deluge of new anime has slowed to a drip. This follows a controversy in February over the anime series Mushoku Tensei. That show was ultimately taken down from Bilibili due to an alleged technical issue — a euphemism for government censorship in China.

This is the latest move by the Chinese government in its ongoing effort to control the tide of foreign media flowing into the country. The full effect of its new policy, and whether it will permanently slow Bilibili’s output, is still unknown. But it may spell trouble for Japan’s animation industry, which increasingly relies on China’s market for anime.

Molly of Denali returns for a second season

On Tuesday, PBS revealed plans for a second season of its educational show Molly of Denali. According to Animation Magazine, the new season will drop this fall.

Since its debut in 2019, Molly has made history more than once, bringing Alaska Native characters and culture to a huge audience worldwide. Per The New York Times, the show “involved more than 60 people who are Alaska Native, First Nations or Indigenous in writing the scripts, advising on cultural and linguistic issues, recording the theme song and voicing the characters.” Molly nabbed a Peabody Award last year.

Kamp Koral scores big TV numbers

Television viewership continues to fall in the age of streaming. That said, one new series still posted strong numbers this year. When it premiered on TV this month, Nickelodeon’s Spongebob spin-off Kamp Koral became the top kids’ telecast of 2021, Deadline reports. Those numbers are doubly impressive when you remember that Paramount+ has been streaming the entire series since early March.

Soyuzmultfilm hit by YouTube reforms

Soyuzmultfilm saw major losses in 2020 because of changes to YouTube’s rules, according to a report this week from the Russian business site vc.ru.

Among other changes, YouTube disabled targeted ads on children’s content in January of last year. Before the tweaks took effect, Soyuzmultfilm’s earnings from YouTube reached 60 to 80 million rubles annually — roughly $800,000 to $1 million. Those numbers fell by half in 2020.

Soyuzmultfilm’s losses track with reports from other children’s channels. In response to its decline in revenue, the studio deleted many of its films from YouTube last October, moving them to the Russian streaming service Premier. This year, they’ve appeared on the platforms KinoPoisk HD and Okko as well.

What’s streaming

The films of John and Faith Hubley have floated around for years in deeply poor quality. Time took its toll on projects like Moonbird and The Hole — by the ‘90s, most versions available weren’t even close to what the Hubleys had envisioned. It’s dampened the impact of their work for too long. That’s why it’s so exciting to watch the six restored Hubley films streaming on the Criterion Channel.

This collection is only a small slice of the Hubleys’ career, but watching Moonbird and the rest in high definition is transformative. It reminds you that the Hubleys are still in a class by themselves. Plus, the length is padded out by the inclusion of two feature films — Of Stars and Men and Everybody Rides the Carousel. No one interested in classic animation should miss the chance to catch these films as they were meant to be seen.

Retro ad — Bop Corn

For all the effort John Hubley poured into auteur films, their total number of viewers is likely only a fraction of the viewership for his 1950s commercial work.

Advertising was a side-project for Hubley, but he broke as much new ground with TV ads as he did with films. He was a pioneer of the so-called “entertainment commercial,” as Billboard dubbed it. This style of ad “tells a story in animated form, making the sales pitch indirectly.” Not long after he started his own studio, Storyboard, in 1953, Hubley came to command the highest fees in cartoon ads.

“It’s no secret in the trade that Storyboard, Inc., is usually the most expensive, with UPA probably a close second,” Billboard reported in 1955. Two years later, the book The Television Commercial claimed that Hubley often charged around $200 per foot of animation — roughly $1,900 in today’s money. One foot amounted to 16 frames in the industry lingo of the time.

Ads like Bop Corn, first aired in March 1955, explain why companies were willing to pay those prices.

Bop Corn is a one-minute TV spot for E-Z Pop popcorn, about a hip, young kernel who tells an older kernel why the product beats standard popcorn. Hubley’s design is abstract and organic, bringing a lumpiness to the characters that mimics the feel of real popcorn. Animator Stan Walsh adds to the effect, freely distorting the cast in radical ways to match the soundtrack and the actors’ readings.

Hubley’s innovative use of jazz in advertising is on full display here, from the music (overseen by Ray McKinley) to the young kernel’s scatting. And jazz slang takes center stage. The spot concludes with the line, “E-Z Pop, man, that’s real bop corn.”

Bop Corn ran for two years and was one of Hubley’s most acclaimed ads from the period. In 1961, the Clio Awards recognized that its “concept and entertainment values have influenced much work since.” As with Hubley’s films, poor-quality prints of Bop Corn have gone around for decades — but you’ll find a beautifully restored copy below. Be sure to set the video to 1080p for the full experience:

Last word

And that’s it! Thanks for reading this week’s edition.

We’re surprised every week by your response to the newsletter. As pleased as we are, though, we’re always trying to reach more readers who share this same passion for animation. If you’ve found yourself enjoying Animation Obsessive on Substack over the last two months, why not share us with a friend?

We’ll be back next Sunday with another batch of animation highlights from around the world. In the meantime, don’t hesitate to check our archives if you’ve missed any of our past issues.

Until next week!

Super cool article really interesting to read about how Russian animators became influenced by modern art, sort of explains why a lot of soviet films ended up being very experimental.

Also great to see Faith and John Hubley's work get the criterion treatment.

Keep up the great work!