A Guide to Yuri Norstein — 'Hedgehog in the Fog' and Beyond

Plus: retro anime gems and animation news from around the world.

Welcome to another installment of the Animation Obsessive newsletter! Thanks for joining us.

This week, we’re starting with a guide to the career of Yuri Norstein, the Russian grandmaster of cutout animation. As you’ll see, Hedgehog in the Fog is only the tip of the iceberg. After that, we’re running down the week in world animation news — and taking a look at anime classics streaming now.

New to our newsletter? We do this every Sunday. You can keep up to date right from your inbox by signing up for free:

Now, let’s get going!

The icons and oddities of Yuri Norstein

It’s hard to write about Yuri Norstein. For decades, he’s been the best-known and best-loved animator from Russia. Gallons of ink have been spilled about him — from Eastern Europe to America to Japan. The Ghibli Museum has exhibited his work. He counts Hayao Miyazaki among his fans. The whole world adores Hedgehog in the Fog.

What else can you say about him?

Despite his fame, though, Norstein’s career is full of bends and alleyways that few have ventured down. He’s been active since the 1960s — and has outlived most of his peers from the Soviet Union. During that time, he’s put out a small but fascinating trickle of animation in his one-of-a-kind stop-motion style.

For your enjoyment, we’ve rounded up as much of that animation as possible — in the highest quality we could find. You’ll find tidbits about Norstein’s career along the way.

Each film mentioned below is linked so that you can watch it for yourself, with subtitles where available. (Animatsiya, a site run by the veteran translator Niffiwan, helps a lot by overlaying subtitles onto embedded videos.) Even if you’re already a Norstein fan, you’ll likely see something here that’s new to you.

The early films

Yuri Norstein is famed as both a director and animator, but he started out in the latter role. Working at Soyuzmultfilm, a state-owned cartoon studio in Moscow, he animated for some of the top directors of the 1960s.

According to Clare Kitson’s book Yuri Norstein and Tale of Tales, Norstein began his career on Living Numbers by Roman Davydov. Developing a knack for puppets, he went on to animate for masterpieces like My Green Crocodile, The Mitten and more. He quickly caught the eye of the doyen of Russian cartoons, Ivan Ivanov-Vano, who championed his career.

Norstein was, like Miyazaki, highly opinionated and particular even in his early years. Soyuzmultfilm was in the middle of a creative boom, but Norstein was still unhappy with many of the projects he animated on. He complained openly.

“I hated myself, the films, the studio,” Norstein remarked later. He grew to dislike puppet animation as an art form, preferring to animate with paper cutouts.

Norstein’s first chance at the helm was 25th – the First Day (1968), a cutout film that he co-directed with Arkadiy Tyurin. It’s a wild, evocative vision of the October Revolution, done in a modernist style. It looks like propaganda at first glance — but Kitson writes that “Lenin was still a hero and Norstein and Tyurin’s revolutionary fervour was genuine.” Government censors were leery of the film and demanded cuts.

While 25th is a little obscure, it’s almost famous compared to Norstein’s sophomore project as a director, Children and Matches (1969). This PSA about fire safety is very nearly unknown, and Norstein has called it “complete rubbish,” but it packs more than its share of charm and invention. Decide for yourself whether he’s been fair to it.

Two final films from Norstein’s early period deserve mention — Seasons (1969) and The Battle of Kerzhenets (1971). He co-directed both with Ivanov-Vano. The first, a whimsical ode to the seasons, is Norstein’s only puppet film. The second is a beautiful cutout project about a legendary battle, rendered in the style of Russian icons.

The famous films

Norstein made his most iconic work in a small window of time, during a flurry of creativity in the 1970s. The key was Francheska Yarbusova, his wife.

Norstein and Yarbusova had married in 1967. She’d helped to design Kerzhenets, and Kitson writes that their “marriage would ... become the most important working partnership of [Norstein’s] career.” Norstein wasn’t much of an artist — his early dreams of painting had fallen through. His true talent was in direction, and in the art of moving premade puppets and cutouts. That’s where Yarbusova came in.

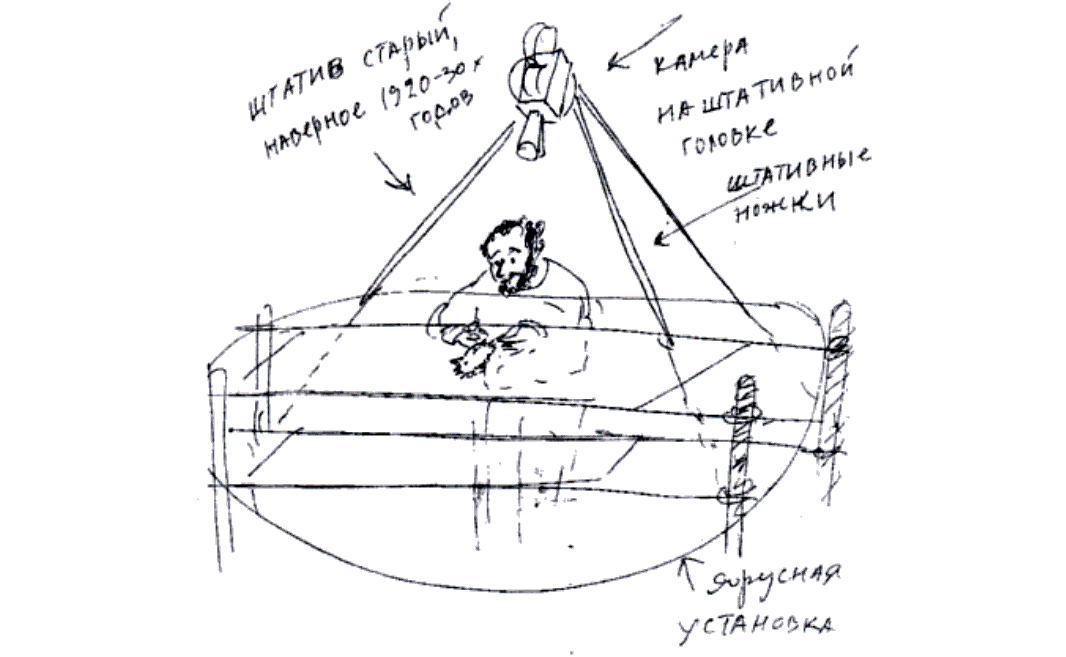

Yarbusova has designed and art directed all of Norstein’s post-Kerzhenets films. Their first major work was The Fox and the Hare (1973), a warm, lovely take on Russian folk art and lore. In 1974, Norstein found his signature style through The Heron and the Crane. He animated Yarbusova’s cutouts atop several sheets of glass layered below the camera.

The characters and backgrounds in The Heron and the Crane are broken into pieces, and those pieces occupy different glass sheets. It creates an odd sense of depth and space.

This technique drives Norstein’s most famous film, Hedgehog in the Fog — a quiet classic that debuted in 1975. The titular fog was made with thin tracing paper. When placed directly over the hedgehog, the paper is almost invisible. Move it several layers up, closer to the camera, and the hedgehog disappears.

Within a few years, Norstein was one of Soyuzmultfilm’s top directors. The saga of what he did next, Tale of Tales (1979), fills a book. To put it briefly, his artistry, boat-rocking and messy workflow combined to infuriate the film approval board Goskino.

Tale of Tales is a dreamlike masterpiece “about simple concepts that give you the strength to live,” Norstein says. It pushes Hedgehog’s look to its limit. And it was banned for several years. The influential Fyodor Khitruk, who co-directed Norstein’s newly-unearthed The Day Before Our Era, was key to saving Tale of Tales from the shelf. And then it took off worldwide.

The late work

A long shadow hangs over Norstein’s late period, and it’s called The Overcoat. He started it at Soyuzmultfilm in 1980 — and he’s still working on it.

The film adapts a story by Nikolai Gogol, and Norstein has displayed it in partial form over the years. (Watch a few minutes here.) It’s by far the most complex and intricate cutout animation of Norstein’s career, and probably of all time. It looks like a painting in motion, but without the paint.

“The first three years were bedevilled by stops and starts and changes,” Kitson writes. It wasn’t ready by its due date of 1986. Norstein ran into another team’s booking and lost his studio space at Soyuzmultfilm, moving his setup into his own home. When the Soviet Union fell in 1991, artists like him suddenly had to rely on private investors.

Kitson once told The Moscow Times that the skills Norstein developed under communism weren’t “helpful regarding survival in a market economy.” Norstein, a critic of the old regime, has been blunt about the new one. “I hate capitalism as a system, … as a method of thought, as a market,” he said in 2016. He opposes Soyuzmultfilm’s recent efforts to privatize.

Over the years, Norstein has made a few small projects alongside The Overcoat. Russkiy Sakhar, a sugar company, hired him to do commercials in the mid-1990s. One is widely available, but the others are tough to find. Luckily, Norstein still shows them at events, and you can see a rare off-screen recording on the Russian social media site VK. The ads reveal an animator transformed, his skills honed since Tale of Tales.

The same applies to Norstein’s opening and ending sequences for the children’s series Good Night, Little Ones! in the late ‘90s. Valentin Olschvang designed them. They were controversial in Russia and didn’t air long — the rabbit’s teeth scared young viewers. But these are gems of cutout animation, with a level of workmanship that defies description.

Norstein’s newest release is a segment in the 2003 Winter Days anthology by Kihachirō Kawamoto. (Watch it here.) The process, which he found even more difficult than The Overcoat, took him between nine and eighteen months. The four sugar ads and Good Night, Little Ones were similar, lasting about a year and a year and a half, respectively

It’s unknown whether Norstein, now 79 years old, will finish his magnum opus. The Overcoat has long since overtaken Richard Williams’ belated Thief and the Cobbler in the record books. Either way, as the master craftsman enters his twilight years, we can all be grateful for the trail of beauty that Yuri Norstein has left in his wake.

Headlines around the world

Animafest and Annecy reveal more projects

Two of the world’s most important animation festivals, Animafest in Croatia and Annecy in France, this week revealed more of their lineup for 2021.

Animafest has picked out 42 projects for its Films for Children Competition. It’s an international bunch, ranging from Iran’s Happy Banana to two shorts from Soyuzmultfilm, Little Snowman and Under the Clouds. (That last film also competes in Annecy’s Young Audiences category.) Find Animafest’s full list of children’s films via Animation Magazine.

Meanwhile, Annecy has unveiled this year’s showcase of works in progress. As Variety reports, this particular showcase is “among the most highly anticipated events of the world’s animation calendar.” Quite a few projects are set to appear, including the long-awaited Maya and the Three by Jorge Gutiérrez. Also announced this week: Annecy’s Mifa Pitches selections, among them the Taiwanese series Who’s Our Sub Today?

Punyakoti continues its march

India boasts a huge animation industry, but it works mostly in outsourcing. Original ideas, and the inspiration to carry them out, can be rare. “Of some 10,000 animators (as in people who just animate to a brief), we may have 10 animation filmmakers who are passionate about making a film using the animation medium,” director Suresh Eriyat said in 2017.

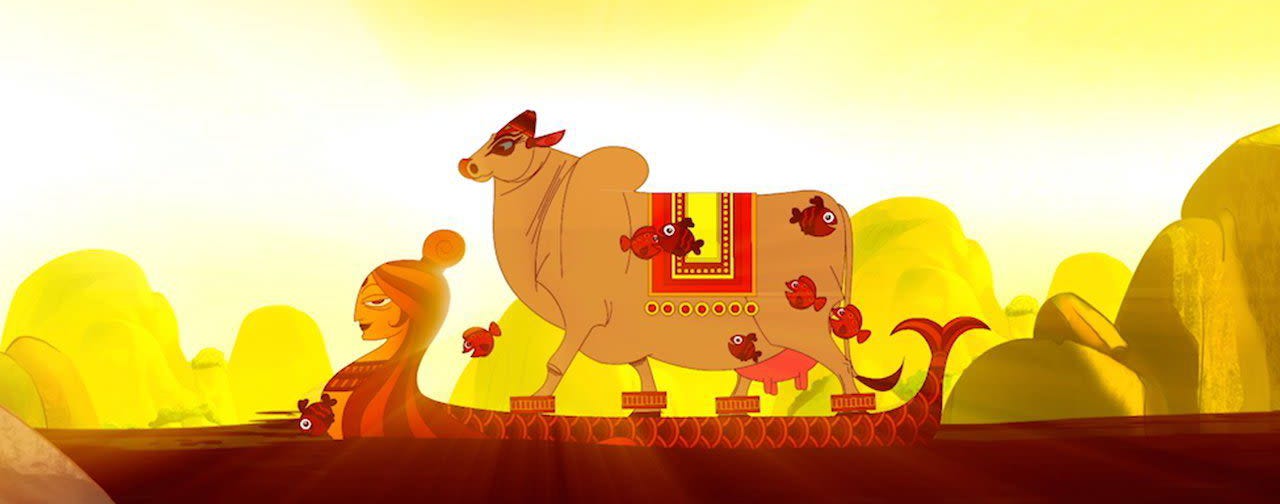

This is what makes Punyakoti, or A Truthful Mother, so interesting. Based on a folk song and billed as the first animated film in Sanskrit, it made waves on India’s crowdfunding platform Wishberry in 2015. The film debuted last year on Netflix, and has drawn eyes at festivals in 2021, picking up an award at a small one in America this week. That follows its selection in April for festivals in Mumbai and Tokyo.

Success for The Mitchells vs. the Machines

Netflix and Sony launched The Mitchells vs. the Machines late last month to positive reviews — it’s currently at 97% on Rotten Tomatoes. This week, we’ve learned that audience engagement isn’t far behind.

Looking at the daily top-10 rankings on Netflix, Sony’s film has seemed to dominate. On Friday, Business Insider confirmed that impression. The Mitchells vs. the Machines was the platform’s most successful film of the week. Despite its last-minute title change and switch to a straight-to-stream release, the film has struck a chord with audiences.

What’s streaming

At one time, access to most classic anime was a luxury for superfans with deep pockets. It’s become easier and easier to watch in recent years — as streaming platforms have filled themselves out by grabbing the rights to rarities and treasures. Services like RetroCrush and Funimation make a business out of it.

But great old anime pops up even on platforms that barely advertise it. Crunchyroll’s brand is built on new releases — good luck finding the beautiful, high-definition remaster of Like the Clouds, Like the Wind it’s streaming right now. The film’s characters were designed by Katsuya Kondō of Studio Ghibli, and it’s quite a bit of fun. Less fun, but still valuable, is Sanrio’s horrifying anti-war fable Ringing Bell.

Meanwhile, Tubi is a general-interest streaming platform, but its collection of A-list retro anime continues to grow. Don’t miss Junichi Sato’s cult favorite Junkers Come Here, about a young girl’s troubled home life and a wish-granting dog. And, if you haven’t seen it on RetroCrush, Tubi’s also streaming Memories. It might be the best anime anthology of all time, and it was all but unavailable in English until recently.

Last word

Thanks for reading! We hope you’ve enjoyed.

If you’ve missed any of our recent issues, you’ll find them in our archives. Last week we published a longread about the animator Jim Simon — a figure the press once dubbed “the Black Walt Disney.” His story is quite a trip.

Until next week!

Thank you for this brilliant guide to Norstein!

Thanks, I learned some new things (or remembered things I had forgotten!). This inspired me to also write something about Norshteyn, with my thoughts about his films. Part 1 is here: https://niffiwan.livejournal.com/39903.html (and part 2 will come soon)