Welcome! It’s the first day of December — the year is almost over. And here’s what we’re doing today:

1) Five animation highlights of the weekend.

2) Newsbits.

Now, let’s go!

1 – At LIAF

There’s one big animation story this weekend, and you’re probably aware of it. The Moana sequel is earning lots of money — which ends a flop streak for Disney. Critics aren’t impressed and industry people are raising ethical questions about the production, but viewers have turned up to watch.

Still, that isn’t the weekend’s only story. As always, another is hiding just below the top headlines.

In London, since November 22, a film festival has been underway. Many shorten its very long, official name — the London International Animation Festival — to the breezier LIAF. For the past 10 days, it’s screened films by artists from around the globe. It wrapped up over the weekend.

A tip from a reader (thanks, Tommy!) inspired us to catch LIAF’s final days via virtual passes. We saw fascinating work from places like Portugal, Czechia and Germany. And Britain’s own genius of collage animation, Osbert Parker, showed a film about the evolving high streets of the UK — told with cut up photos of storefronts across the years. Luckily, that one’s online for free.

Most of the others aren’t yet, though. This includes Adios, directed by José Prats — one of our favorite films of the festival.

It’s hard to shoot puppets in stop motion. Even with the help of greenscreen and digital effects, you’re dealing with objects in front of a camera. That forces you to answer the same questions as a live-action filmmaker. Is the lighting right? Does the angle work? Can the viewer keep track of the physical space between edits?

Then there’s the other, greater question: do these inanimate things express character?

Adios navigates all of the above. It’s set in the Spanish countryside, and you feel the late-summer heat through the light, the wind through the rustling shrubs, the size and shape of a room through the smack of a kitchen knife into a cutting board. The staging is clean and sharp, and the editing undistracted, from the opening.

Here, an aging father and his adult son have a strained relationship. The son is leaving for London; the father feels abandoned. They go for one last rabbit hunt, hitting nothing. “Don’t worry, Dad. It was a long shot anyway,” says the son. The father, looking into the field, replies that his eyes are failing.

He starts to turn toward his son, then hesitates, then commits to it — like an actor. His son, glancing away, doesn’t speak.

José Prats co-directed the viral and very good Umbrellas (watchable on YouTube) a few years ago. Lately, he was behind the color script for Aardman’s Over the Garden Wall short. He shows again in this film that he’s an artist to watch. There’s filmmaking you can’t fake in Adios, and it tells a real, meaningful story — all in eight minutes.

Prats works in England, but he’s from elsewhere (Spain, to be specific). Gabriel Böhmer has a similar background. He’s a Swiss animator based in the UK — and his film Progress Mining intrigued us at LIAF.

We’ve come across Böhmer’s stuff in the past. His Push This Button If You Begin to Panic stood out when we were on the jury for a Canadian festival in 2021. “Thoroughly entertaining. Unique visual tricks and ideas throughout. … Very funny and surreal dialogue and plot progression,” our internal notes read at the time.

Similar things could be said about Progress Mining. It’s a dry, strange satire about a mining company and its latest employee. Never mind what they’re mining, he’s told. Never mind the crude sign on the wall about worshipping a monster — or the hallucinogens in the tea.

There’s some sort of technical problem with the operation, too, but the boss refuses to shut things down to fix it. “If we shut, we can’t pay people. I don’t want to put anyone in that position,” he says. “You know, I stand in solidarity with the workers.”

Böhmer’s style of animation isn’t a familiar one. He favors a kind of homespun cubism — realized in stop motion through an assemblage of cutouts and odds and ends. The look embraces imperfection, and it’s a delight to follow along with the skewed visual solutions he finds for each shot.

“My original background was in management consulting,” Böhmer’s said. In the 2010s, though, he wrote a novel, got into art, joined a band — and learned animation to make a music video. Progress Mining is the result of years of moving in that last direction. Only its sudden ending detracts, but Böhmer has implied that there may be more to this story down the line.

Adios and Progress Mining are certified festival films: it’s where they fit, where they make sense. This is their ecosystem — thankfully, they have one. Projects this quiet and hyperspecific rarely get to be YouTube hits.

That said, even the festival circuit isn’t perfect. It has its own biases and cliches.

Recently, animator Konstantin Bronzit (an Oscar nominee) posted a semi-satirical guide to festival success, especially in his home country of Russia.1 Lean on sentimental music, he argued. Exploit stories of other people’s real suffering to get attention. “God forbid you use a funny story — no one needs that today,” he added.

You don’t have to agree with Bronzit’s cynicism to get the argument. Sometimes, even in festivals beyond Russia, there are only a few films with laugh-out-loud comedy or a sense of fun — except in the children’s slots. And then another bias comes in.

Last year, director Britt Raes (of the wonderful Luce) said that children’s artists can be “treated differently” by festivals. They don’t “always support filmmakers who make stuff for kids in the same way.” She told Under the Onion Skin:

… we put a lot of hard work and thinking into it as well. And we were very dedicated, just like all the other filmmakers. ... We can tell challenging and interesting stories and show interesting characters [too].

All of which is a preface to a point: some of the best executed, most entertaining and most memorable films of LIAF 2024 were in the children’s categories. In fact, several of them were picture book adaptations.

See Für immer Sieben, for example, which comes from Germany. It’s about seven adult animals who each stumble upon the same wooden box. The crocodile sees it as a magician’s prop; the cat as a romantic dinner table. Misadventures ensue. It’s a film based on the old toolkit of animation: visual gags, funny lines and full, expressive cartooning. To quote a German review, it’s “an entertaining and good-hearted short film and one not only for young viewers.”

Then there’s Writing Home by Eva Matejovičová, a Slovak animator whose work in animal rescue colors her films. This one is a student project — she did it for her bachelor’s degree.2 And it’s really impressive.

Writing Home is about a bug who lives happily in a tree — alongside an entire bug society. Then a stray cigarette starts a fire, and the devastation begins. One of the bug’s arms is burned down to a stump, and she ends up adrift in a stream. In what feels like a nod to Abel’s Island, she’s cast away to live on her own.

Soon, she finds herself on the windowsill of a human grade school. She learns by watching the class to write English letters with her burnt stump, and slowly the seasons change. As the forest starts to regrow, she finally returns home.

It’s told in a childlike register — and, like Für immer Sieben, is full of humor, fun design and charming animation — but this is a film about a refugee.

Matejovičová and her team did a lot here. Many other refugee stories at LIAF, like Margarita’s Story (on YouTube), cut closer to the bone and cover real-world tragedy. They deserve serious attention. But there’s something to be said, too, for a film that can address these problems in the language of children’s literature. Stories like Abel’s Island are classics for a reason: they use universal means to talk about difficult things.

At LIAF this year, most of the films for the youngest viewers were interesting. The festival’s own award pick in the category, for instance, was the joyously annoying Animanimusical (also on YouTube) by Julia Ocker of Germany. It’s hard to forget.

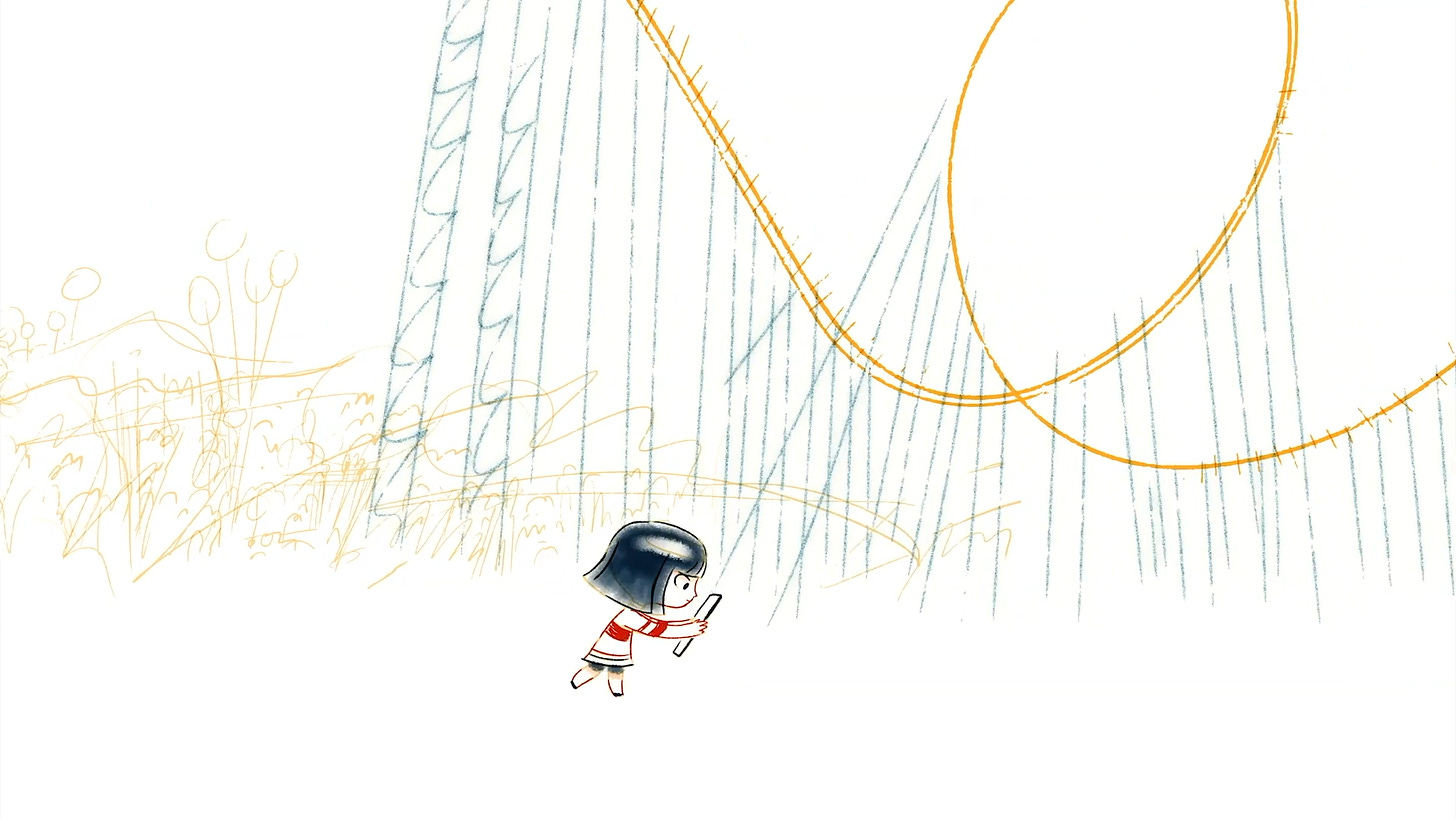

Still, as a piece of pure animation, the one that grabbed us most was The Girl with the Occupied Eyes. It’s from Portugal and, once again, it adapts a children’s book.

Author André Carrilho oversaw the film version himself. He was really involved: the credits list him solo as director, art director, storyboarder and compositor — and as one of the three key animators. What he and his team have made is gorgeous.

The movements are loose, fluid and full of character — and they happen in a world in progress. Lines draw themselves in; construction sketches are visible beneath. Richly textured watercolors splash and run across the screen, transforming outlines into trees, rooftops and walls. Then things disintegrate, and we move to the next scene.

The look owes things to Cartoon Saloon (Song of the Sea), but it’s fresh. So is Carrilho’s story, about a child glued to her phone. She marches along to a fun jazz score, barely aware of the bizarre world around her — including pirates and a trip to outer space.

After the credits, we get a message from the team. “This film was entirely made without the use of AI,” it reads.

As Carrilho told the Portuguese press, the crew relied on its ingenuity to bring his book illustrations to the screen. That involved “a hybrid of paint blot footage with traditional hand-drawn animation,” plus digital watercolors. As he said:

I think that these days we have to reaffirm that things are made by people, and this whole film — from the music that was played by musicians, with real instruments, [to] the hands that designed each character — was all [the result of] individual decisions by people, from a Portuguese team, everything made with our hands and our creativity.

The Girl with the Occupied Eyes is a film with no pretensions — it’s not aiming for an Oscar. Sometimes, though, the best films are simple ones that focus all their energy on execution. Great craft can elevate anything, and you find it here. Carrilho and his team offer a reminder that the light films can mean a lot, too.

2 – Newsbits

In America, The Animation Guild reached a potential deal with Hollywood. Its full details aren’t public, but the summary mentions “AI protections that include notification and consultation provisions.”

Nathan Connelly, an American animator, set out to “replicate the look of John and Faith Hubley’s multiple exposure animation technique entirely in the computer.” He shared some of the results, and his process, on Bluesky.

The Japanese publisher E-SAKUGA is doing a digital book on Mary and the Witch’s Flower, letting readers tap through the animation frame by frame. Its past work (like its book on Gauche the Cellist) has been essential, so this is good news.

Mattias G is an animator from Sweden whose work calls to mind Moebius and Scavengers Reign. His latest YouTube film, Collecting Teledust, came onto our radar this week.

Another from YouTube: Ian Worthington, the American animator, is back with a new short called Wall Gnomes. It’s very funny — as usual.

Australia’s Glitch Productions is dropping a new episode of The Amazing Digital Circus in December. See the trailer.

A studio named Pungulu Pa is finding a way forward in Kenya. “At the beginning,” says co-founder Chief Nyamweya, “the critics were right because it was too expensive to make animation in Kenya and it was much cheaper to outsource to India ... But we have proved them wrong in the end.”

Bilibili’s been a huge force in Chinese animation for years now — and it just turned a profit for the first time. Wuhu Animator Space explored the details.

Also in China, Anim-Babblers published two long interviews with animation veterans of the ‘90s and ‘00s. They discussed outsourcing, industry and the specifics of the low years of Chinese animation.

Lastly, we worked with journalist Andrew Osmond and historian Jonathan Clements on a story about Atsuko Fukushima, the great animator.

Until next time!

Thank you so much for the review of our film! It made my day.

Not gonna lie - I’m a little mad about the aninimanimal thing… that’s gonna be stuck in my head for days.