Welcome back! It’s a new Sunday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s our lineup today:

1️⃣ The story of Richard Williams’ ambitious, controversial Christmas Carol.

2️⃣ Worldwide news items in animation.

Just finding our newsletter? You can sign up for free to receive our Sunday issues in your inbox, weekly:

With that, here we go!

1: Richard Williams for the holidays

By the late ‘60s, the papers were already repeating it. “The new Disney,” they called him, again and again.1 His name was Richard Williams. He was an animator in London — running a studio at 13 Soho Square.

Just what the two men had in common wasn’t clear. Williams was a Canadian, first of all, and he’d moved to Europe during the ‘50s to pursue a bohemian life of painting and jazz music. Still in his early 20s, the idea gripped him to create a cartoon with modern graphics, like UPA. It was The Little Island (1958), made over three-and-a-half years.

Williams paid for that film chiefly with ad work. He spent one year subsisting by and large, as he said, “on peanut butter sandwiches and milk.” The Little Island didn’t make money, but it got awards — and press. He tried his hand again with Love Me, Love Me, Love Me (1962), another artsy festival film, and this time landed a hit. Bigger offers arrived: animated title sequences (What’s New, Pussycat?) and even more ads.

By 1963, Williams led a small team. Their key breakthroughs were work-for-hire jobs, especially the animated scenes in the live-action Charge of the Light Brigade (1968), which copied the look of 1800s illustrations. Chuck Jones, affiliated with ABC in America at the time, saw that animation and was blown away. It gave him an idea.

“I thought how it would be to do a definitive Christmas Carol … in the steel engraving technique of the 1840s,” Jones said.

Christmas specials were a booming business — after a few annual reruns, stuff like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer paid for itself, and everything afterward was pure profit. Plus, Jones called it “the dream of a lifetime to be able to do something in animation using the original illustrations.”2

Jones had been a Williams admirer for several years, and they knew each other. Still, it scared Williams to take such a tough job. A Christmas Carol (embedded below) would be made anyway, against all odds.

There’s no shortage of great Christmas animation — A Charlie Brown Christmas, The Snowman and more. You find top artists and directors in the credits to many of these projects. Even so, it’s a little odd to learn that the animator behind Who Framed Roger Rabbit and the vast, unfinished Thief and the Cobbler directed a Christmas TV special.

A Christmas Carol is a less-covered chapter of Richard Williams’ life, but it was still hugely ambitious and risky. The mandate was authenticity. Like Jones said: the definitive filmed version of A Christmas Carol.

During production, there were signs on the walls of Williams’ studio: “we are doing this show as Dickens would do it if he were the producer.”

As a result, A Christmas Carol began with a breakneck, six-week stretch of research in England. With Dickens himself in the producer chair, every inch of the special had to be period-accurate. Williams said in 1972:

We had copies of Illustrated London News and Punch from 1840 to 1860. We went to the British Museum and made Xerox copies of everything. Then we went through London — there are so many things still in existence from that period — and did some 25 drawings each of doorknobs, actual doorknockers, Scrooge’s socks.

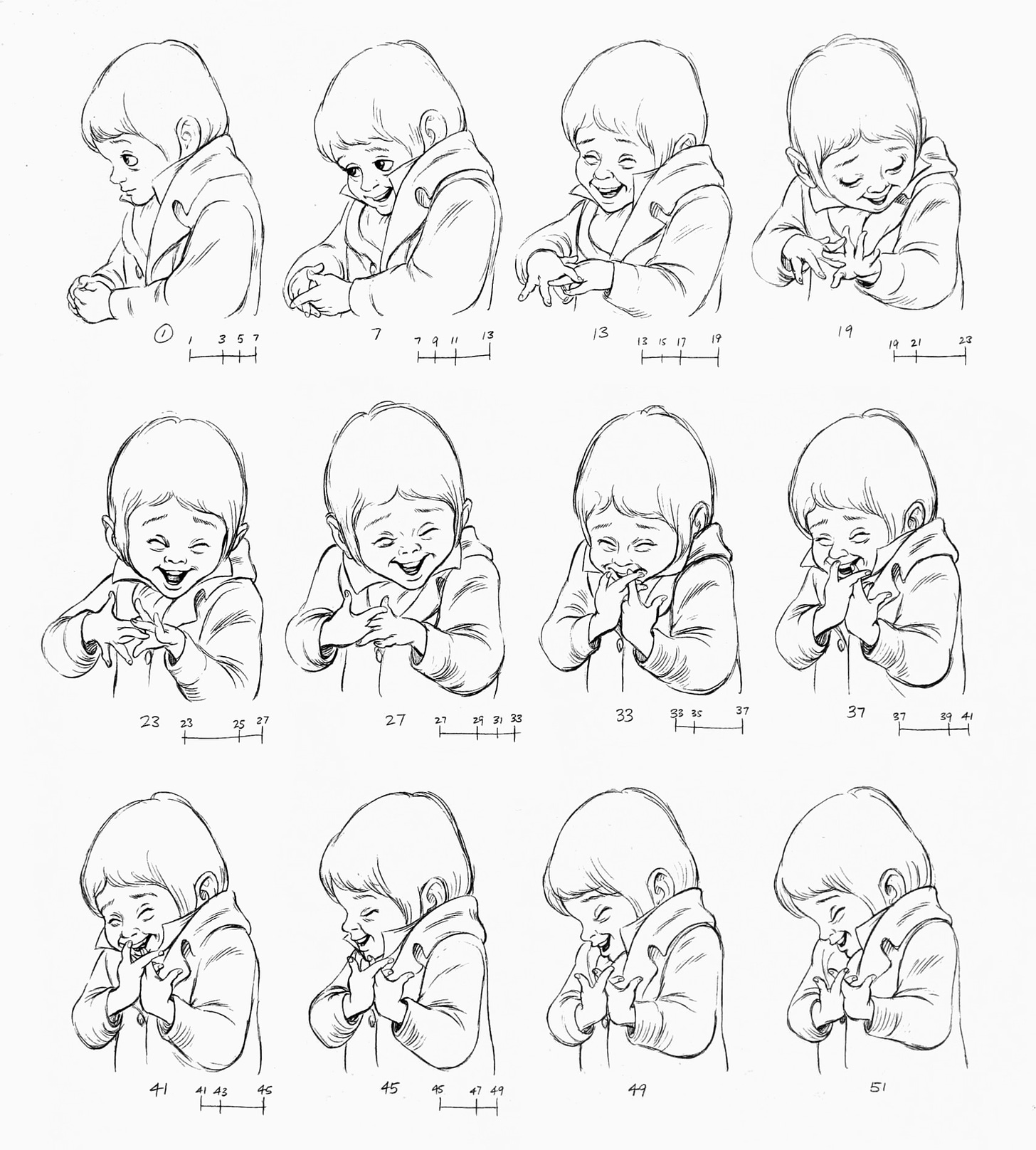

The team was allotted nine months to make 25 minutes of animation in the style of John Leech’s illustrations. That meant 30,000 drawings. Full production took only seven of the nine months. “We slept under our desks and everything for this thing,” said Williams. “It was a tremendous race against time. I remember I was doing nine backgrounds a day as well as animating, as well as cleaning up, as well as directing it.”

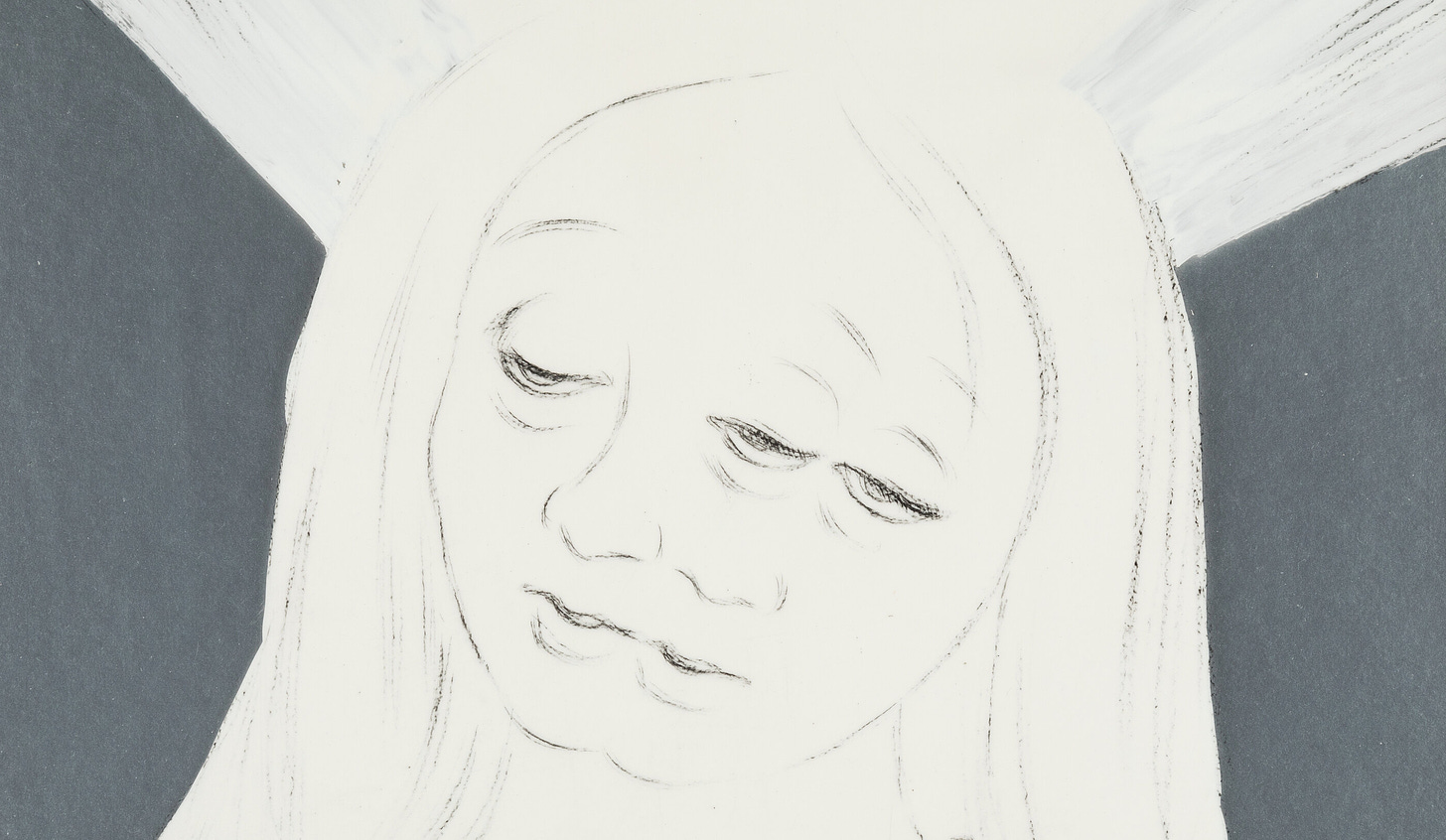

Jones’ idea to copy Light Brigade outright was impossible on this schedule, as Williams refused to save time by using limited animation. So, the team ditched the polished and rendered look of Light Brigade for a rougher “drawing-style version of the old illustrations.” The animators sketched directly on cels with grease pencils. It was just barely fast enough.

The dialogue, stage direction and narration came from the book, although condensed. “Dickens apparently was not informed that TV shows run 26 minutes [so] we did have to cut a bit,” Jones told the Los Angeles Times in 1971. “If you do it exactly as Dickens wrote it, it runs 33 minutes.” Still, no original lines were added.

Williams, for his part, was surprised at how taken he was by Dickens’ book when he read it for research. He hadn’t engaged with it before, and had disliked the film adaptations. As he said:

I found it was nothing like the Christmas Carols I’d seen. I called up Chuck Jones ... and said, “Hey, look, this is frightening. It isn’t a sloppy sentimental thing. It’s about ghosts. Do you really want it?”

He did. The concept didn’t scare away the network or the sponsors, either. A Christmas Carol received a big budget of $300,000 (over $2.2 million today). Williams was able to put 25 full-time staffers on it.3

The most crucial of these staffers was the lead animator, Ken Harris. He was a veteran of the industry. Harris was a Warner guy, in his 70s, who’d come out of retirement a few years before and become Williams’ mentor. “Dick and I had been corresponding,” Harris said in 1975. “Chuck Jones had told me, this guy’s a marvel. He can pick your work out in any film — never misses. So I came over on holiday and met him.”

Before, during and after A Christmas Carol, Williams and Harris worked closely. The younger animator picked up many lessons (and tics) along the way. It was Harris who served as Williams’ model for the design of Scrooge. His hands appear in the special.

Jones once said:

Dick Williams adores Ken Harris. … On A Christmas Carol, he was sitting at the desk, and Ken was sitting on a stool behind him; Dick would make a drawing, and then Ken would tell him how to change the drawing. They were working as a team, Ken sort of directing Dick in action. Ken animated most of Scrooge, but he couldn’t draw him. So Dick acted as a clean-up man.

Although Williams had started his career as a UPA acolyte, he’d come to idolize the old men of the industry — particularly Disney’s animators. By the time of A Christmas Carol, Harris was just one of his role models. Another was Milt Kahl, the cantankerous and technical animator of many a Disney character. Williams had sent Kahl a fan letter after seeing The Jungle Book (1967), picking out Kahl’s work by sight.

The Jungle Book, when contrasted against the post-UPA trip Yellow Submarine (1968), was a turning point for Williams. A few years later, he said this:

Yellow Submarine convinced us that we wanted to be finished with the kind of animation based on graphic tricks. The Jungle Book — leaving aside anything you may feel about its aesthetics or narrative methods — was a revelation. We realized how much Disney’s techniques and discoveries had still to teach us; and we wanted to go back to school, to Grade One, to learn how to make a character live and walk and talk convincingly.

Williams was an accomplished animator in the UPA vein, but he became one of the very, very few to reject the revolution. “As one of the ‘modern’ animators, or rebels against the traditional approach, I realized that much of what we were doing was only short term ground-breaking,” he said.

In the late ‘60s, his studio began to analyze the early films from Disney, Fleischer and even Winsor McCay, practicing their techniques. “We studied ... until we knew all the tricks of the trade and got our chance to try them out with A Christmas Carol,” said Williams. In a sense, he found himself turning into a sort of cartoon reactionary: as an animator, if not as a graphic designer, he preferred the old ways over the new.

Disney was passé among animators worldwide when Williams made A Christmas Carol, but it wasn’t passé for Williams. He wanted to save the classic approach before it disappeared. This special was, for Williams, a “trial run” for a certain feature film he was developing: The Thief and the Cobbler.

A Christmas Carol made it out before Christmas 1971, but barely. The special cut it so close that, late in production, Chuck Jones sent over a crack team from America. One member was Abe Levitow, the director of the first animated Christmas special (Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol, 1962) and an ace animator in his own right.

It’s a testament to the abilities of Williams, Jones and the team that the project turned out, given the time limit. The workload was devastating enough that Williams remembered needing a whole three months to recover.

Despite all that, he didn’t loosen his standards. He was one of the most notorious perfectionists ever to work in animation — even with a seven-month production period, Williams refused to take shortcuts. Martin Hunter, a childhood friend, often stopped by the studio during A Christmas Carol. He remembered:

Every Friday he and his staff screened the week’s work and we would go with the kids and watch in a little basement projection room. Dick paid close attention to the kids’ reactions and once when [my son] Ben asked, “Didn’t we just see that a minute ago?” Dick flew into a rage. A young animator had used one bit of footage twice to save time and Dick insisted the whole sequence be done again, even if it set back the work by nearly a week. On another occasion, we were joined at the screening by Alastair Sim, who was supplying the voice of Scrooge. He cackled delightedly throughout but insisted on redoing three sequences. He was a perfectionist, as was Dick.

The team aimed high with its motion and camerawork, too. Williams said that he despised the “flatness of animation,” that stage-y quality. For the standout moment when the Ghost of Christmas Present flies Scrooge around to different holiday celebrations, the team went all-out. “It only runs about 15 seconds on the air,” Jones said, “but it took over a month to animate that one scene alone.”

This brash excess and attention to detail paid off. When ABC premiered A Christmas Carol on December 21, 1971, the special was a “tremendous success,” according to Williams. Jones took the steps necessary to get it nominated for an Academy Award, which was still possible for TV specials at that time.

“He put it in for an Oscar nomination,” Williams explained. “I never would have done so. He ran it in Los Angeles so that it would qualify. He was wonderful!”

A Christmas Carol ultimately won the Oscar, changing the course of Williams’ career in the process. Hollywood took notice. The endlessly repeated nickname that Williams hated — “the new Disney” — stuck. Even he had to admit that it helped him in the business.

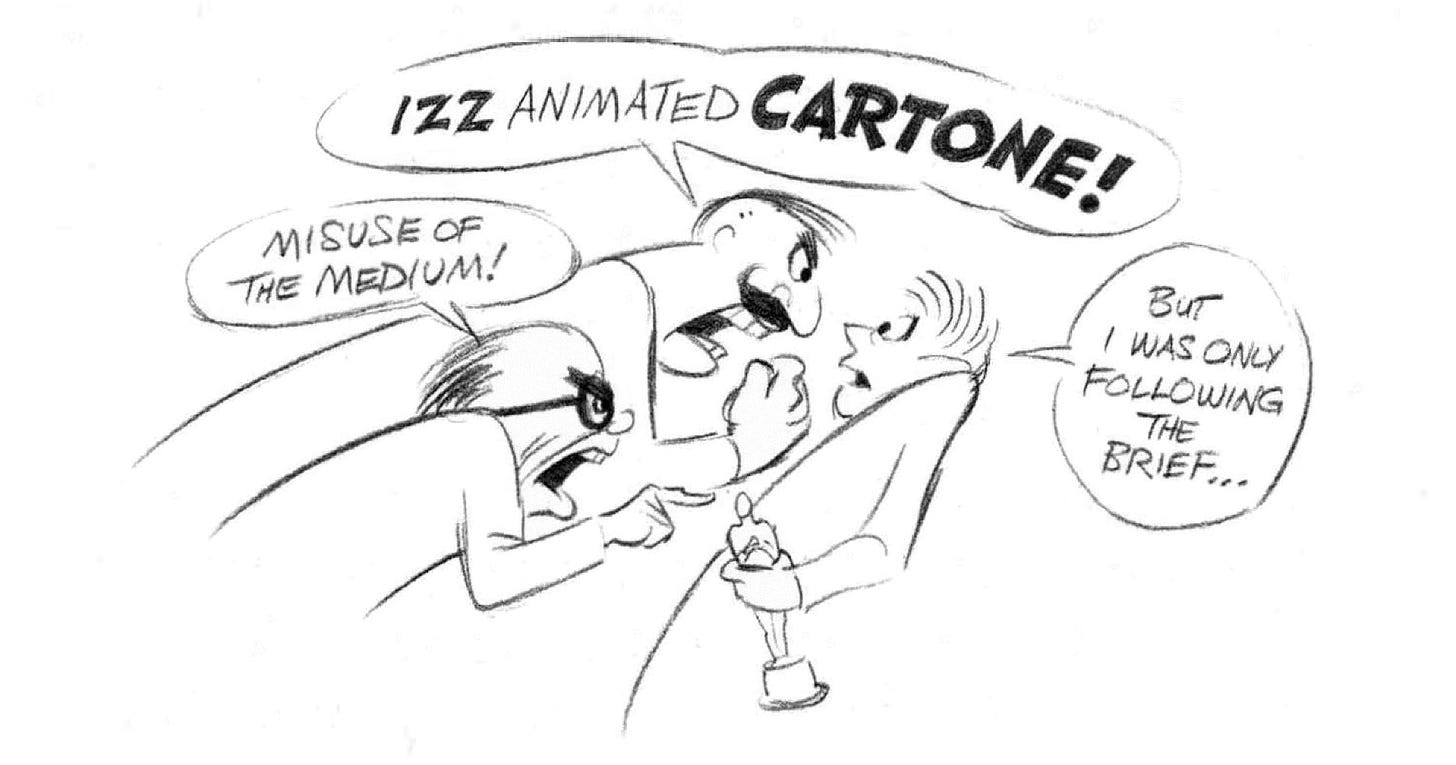

Yet the industry’s artists didn’t all agree with the businessmen about Disney, or about A Christmas Carol. There were clear, contentious battle lines drawn at that time between Disney’s cartoons and the cool, exciting stuff — especially in Europe.

“A lot of his erstwhile admirers felt themselves positively betrayed to see him revert to the long-out-of-fashion Disney style against which UPA and Williams himself had so violently and effectively reacted,” reported Sight and Sound in 1973.

The blowback to the Oscar win was immediate. Williams noted that Bill Melendez (A Charlie Brown Christmas) and Ward Kimball (Disney’s leading mid-century modern artist) cornered him. “They felt I was a traitor to the medium because I’d gone too close to ‘realism,’ ” Williams wrote.

When A Christmas Carol screened in Zagreb during 1972, the reception was even icier. As a journalist noted in Movie Maker:

Chuck Jones’ Anglo-American production of A Christmas Carol starts the evening and divides us all. [Gene] Deitch is wowed by the wonderful drawing; everybody else hates it. Dick Williams’ animation is perfection, but who needs it? The film could have been of real actors — and probably, in the beginning, was. It looks traced from life.4

It wasn’t traced, but even Williams came to believe over time that the drawing style had been too realistic.5 Cartooniness was dogma in animation back then. Still, he stood by his animation techniques — as uncool as they were.

The whole dispute sounds silly now. We live in a time when people freely enjoy, and combine, the ideas of Disney and UPA. The Thief and the Cobbler and the Hungarian school of animation (which borrowed a lot from Yellow Submarine) are equally visible in the films of Cartoon Saloon, to name one. And A Christmas Carol, while a bit fast-paced, is a good watch today. It rivals and arguably beats the famous Magoo version.

But no one back then had the benefit of hindsight. They were in it — and the stakes were high. Williams was keenly aware that the old principles of animation might vanish altogether. The UPA and post-UPA rebels felt crushed by the weight of the Disney mentality, that resistance to modern ideas, and they wanted to be free from it.

People chose their sides. We’re lucky that we can appreciate A Christmas Carol now without picking one. And we can see that, despite his swing toward Disney, Williams hadn’t really abandoned his UPA roots. A Christmas Carol itself was a fusion. To quote historian Adam Abraham, the secret of UPA was that “the artists had the flexibility to give each … film its own look, appropriate to its subject.”

And so it was.

This is a revised reprint of an article that first ran in our newsletter on December 15, 2022. It was exclusive to paying subscribers then — just under a year later, we’ve made it free to all.

2: Newsbits

Swiss animator Dustin Rees has put his film Signs out for free. We loved it during its festival run — its portrayal of everyday movements and relationships is full of observation, care and specificity you can’t fake. (Zippy Frames talked to Rees for the occasion.)

Jonni Phillips, the American animator behind Barber Westchester, released the trailer for her next feature film: Take Off the Blindfold, Adjust Your Eyes, Look in the Mirror, See the Face of Your Mother.

Another from America: Across the Spider-Verse’s screenplay is now online. (The one for Into the Spider-Verse is available as well.)

The French-animated film The Inventor hit VOD last month — places like Vudu and YouTube have it, as does the free library service Hoopla.

In Japan, a distressing story got a happy ending. Thanks to Toho, Tokyo Laboratory won’t destroy those thousands upon thousands of anime masters.

In Russia, the latest round of state support for animation all but excluded directors from the renowned, independent Shar, among them Anastasiya Lisovets (Dogs Smell Like the Sea). “We love to look for the ‘canceling’ of Russian culture at international festivals,” writes scholar Pavel Shvedov, “but it, perhaps, is lurking in completely different corridors and minds.”

In Spain, Robot Dreams is up for four Goya Awards. This 2D feature is winning praise everywhere it goes — find a clip here.

Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron opens in America on December 8, with preview screenings on the 4th. Ticket presales are high, says distributor GKIDS, and hype is building: the NYFCC awarded it Best Animated Film this week.

The Imaginary, directed by Yoshiyuki Momose of Ghibli fame, premieres in Japan later this month. Its marketing campaign includes TikTok behind-the-scenes videos, promotions with McDonald’s and more.

In England, Mog’s Christmas is the new TV special from the consistently interesting Lupus Films (The Tiger Who Came to Tea). It airs later this month.

Bubble Bath (1980) is a Hungarian classic, and it’s getting a restored Blu-ray release in English via Deaf Crocodile. See the trailer.

Inside Europe’s co-production ecosystem, Sidi Kaba and the Gateway Home just won another €382,000. Director Rony Hotin (France) says that he aims to “reconnect with [his] ancestry” and “plunge children into an epic adventure” with the film.

Lastly, we told the story (in detail, for the first time in English) of the making of Roujin Z. It’s one of our favorite pieces we’ve published this year.

See you again soon!

The “new Disney” label turned up in The Tampa Tribune (October 30, 1969) and other papers, but that was neither its first nor its last appearance. By 1973, using the term to describe Williams had become a cliche. He himself lamented “the awful sort of journalistic publicity I’d been getting that insisted on calling me ‘the New Disney.’ ”

The main sources for this first leg of the issue are The Kingston Whig-Standard (October 26, 1973), The Gloucester Citizen (December 27, 1958), The Salem News (November 25, 1971), the Lancaster New Era (December 14, 1971), Seventeen (December 1973), Films and Filming (October 1963) and Sight and Sound (Spring 1963).

For this second part of the article, we relied primarily on the Progress Bulletin (December 19, 1971), the Deseret News (December 9, 1972), The San Bernardino County Sun (December 13, 1972), the Nassau edition of Newsday (November 26, 1972), the Los Angeles Times (December 19, 1971), the Omaha World-Herald (December 10, 1972) and this blog post by David Nethery.

The attacks on A Christmas Carol in Zagreb were about the animation style, but a political dispute came in, too. As reported in that same article from Movie Maker (September 1972):

Chuck Jones presides at the press conference and is slaughtered. European film critics castigate his capitalistic decadence for apparently proposing that the solution to world-wide poverty is charity. Shaking, Chuck says you don’t have to like fish to admire Picasso, but they won’t let him off the hook.

It’s worth noting that A Christmas Carol somehow walked away with Zagreb’s second prize for “films longer than 3 minutes” that year, despite the controversy.

Williams mentioned this in the Los Angeles Times (May 18, 1975). Two final sources that helped us to complete the issue were articles in The Guardian (December 24, 1975, February 24, 1973), which gave us the quote from Ken Harris and key details from Williams.

I think watching 'Raggedy Ann' made me more appreciative of Williams than I was before, so I went into 'A Christmas Carol' with an open mind this time. I enjoyed it quite a bit, even more with all the context you provided. I disagree with the contemporary notion that this was a waste of effort for not utilising the strengths of the medium. I love animated films that bring to life a specific style of illustrated art, and this one ranks among the most mesmerising examples. The greyish, sketchy look greatly aided the haunting atmosphere, and you couldn't integrate ghosts as convincingly in live-action. In the sound department, the lack of music struck me as an excellent choice, and Alastair Sim is so good!

PS: A little tip. La Cinémathèque française is streaming 9 restored Ukrainian animated films on their platform 'Henri'. Some are very interesting. https://www.cinematheque.fr/henri/#ukranima

I must have missed this the last time. Great read! I am glad the ReCobbled channel has so many Richard Williams stuff to share, including the really nice upload you included in the article. When I was still in school I would have probably have thought this was not "cartoony" enough but being a little older I can appreciate more what Richards et al. did, especially with how full body characters move.

I think to myself though, that man on the boat during the "flight" section, that has to be rotoscope, no? It looks like live action with a photo filter.