Animating an Oscar Winner (Secretly) Behind the Iron Curtain

Plus: animation news.

Happy Sunday! It’s time for another issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s the plan:

1️⃣ On Munro (1960), the first foreign cartoon to win Best Animated Short.

2️⃣ Animation news from around the world.

Before we continue — only readers fuel this newsletter. We’d love for you to join us:

And now, let’s go!

1: International exchange

The Oscars are often spotty about honoring animation made outside America. Just one Japanese film, Spirited Away, has ever won Best Animated Feature — and Satoshi Kon received zero nominations in his lifetime.

In fact, it took around three decades, until the 1960s, for a non-American cartoon to win an animation Oscar at all. A film named Ersatz from Yugoslavia claimed the prize in 1962. It was a milestone, and it inspired that Worker & Parasite bit from The Simpsons. Many, many books call it the first foreign cartoon to take home the Oscar.

But Ersatz wasn’t the first — not exactly.

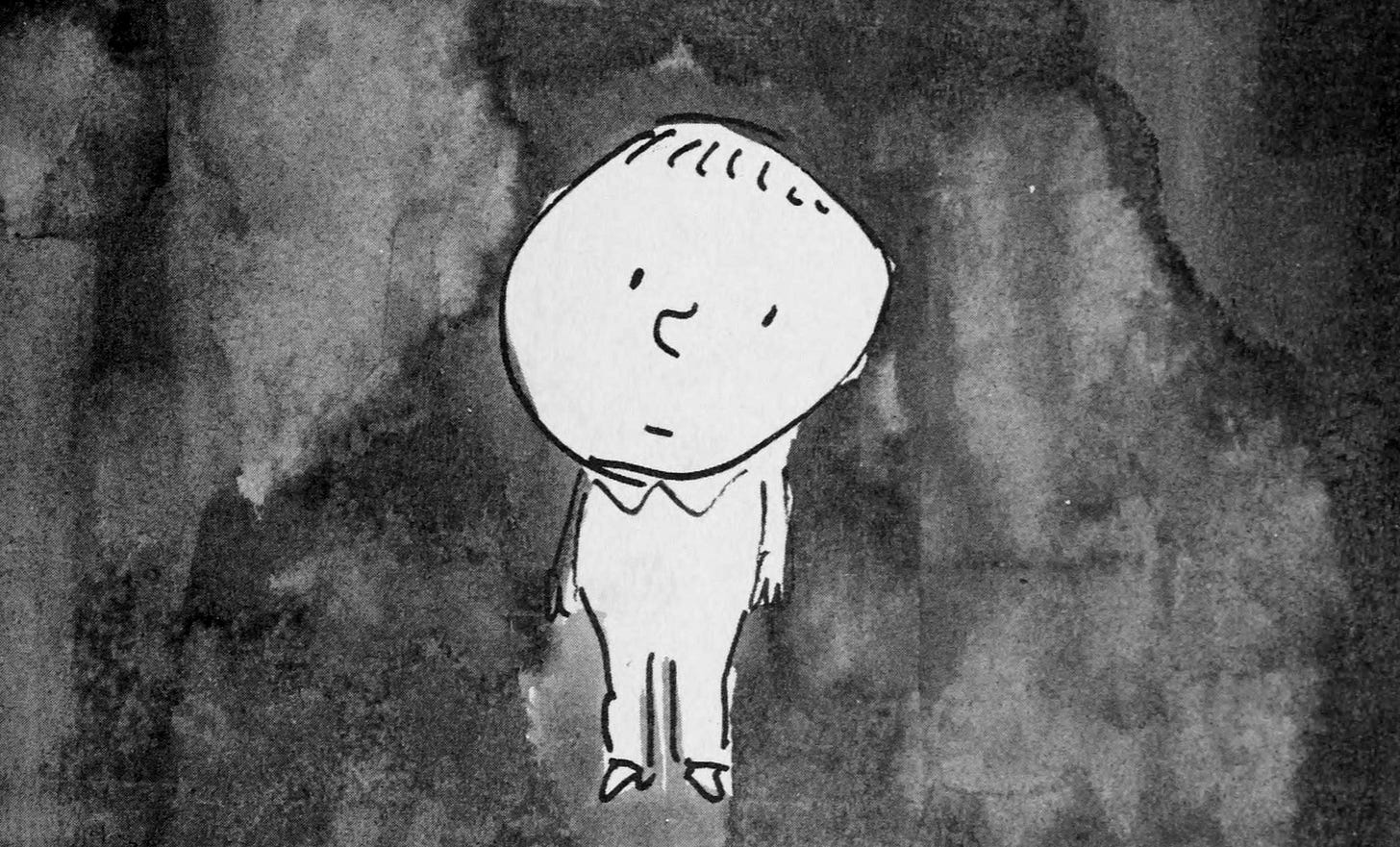

One year earlier, the award for animated short went to Munro (1960), a charmingly vicious satire of the Army. At first glance, Munro looks all-American: it’s in American English, it hits American comedy beats and it’s about the United States. It follows a four-year-old boy, Munro, who gets drafted by mistake. In a sort of catch-22 before Catch-22 was published, Munro can’t leave the Army because children officially can’t be drafted, and therefore he can’t be a child, and therefore he has no excuse to leave.

The thing is, Munro (watchable below) wasn’t animated in the United States. Its script and dialogue and planning were done stateside, but the film was outsourced to a studio in communist Czechoslovakia. Munro was an Oscar winner made secretly, even as the Cold War raged, behind the Iron Curtain.

Munro’s winding story began in the early 1950s. The idea started as a book. Its young author, Jules Feiffer, wanted to be a print cartoonist but was then in the Army. He wrote and drew this satire about a four-year-old draftee — finishing it in 1953. It didn’t pan out. “Munro was rejected by every publisher in New York,” Feiffer recalled.

Eventually, the piece was printed in Feiffer’s collection Passionella and Other Stories (1959), which became a hit. By that time, he was already working with the man who would turn Munro into an animated film: director Gene Deitch.

Deitch was one of the top people in East Coast animation. For years, he’d been in charge of UPA New York, spearheading the mega-popular Bert and Harry Piel series. In 1956, Deitch went to the New Rochelle outfit Terrytoons (known for high-volume, low-quality animation) and revived it with fresh and exciting hires. Feiffer was among them. “He was just the man to help me instill new life in that moribund studio,” Deitch felt.

They did great work at Terrytoons, but the studio’s old blood (people Feiffer called “outdated but amiable hacks”) ultimately outlasted the newcomers. Feiffer left, and Deitch was forced out. In August 1958, Deitch opened his own studio and hired Feiffer again. It was Gene Deitch Associates in Manhattan, on West 61st Street.1 That’s where the animated Munro got going.

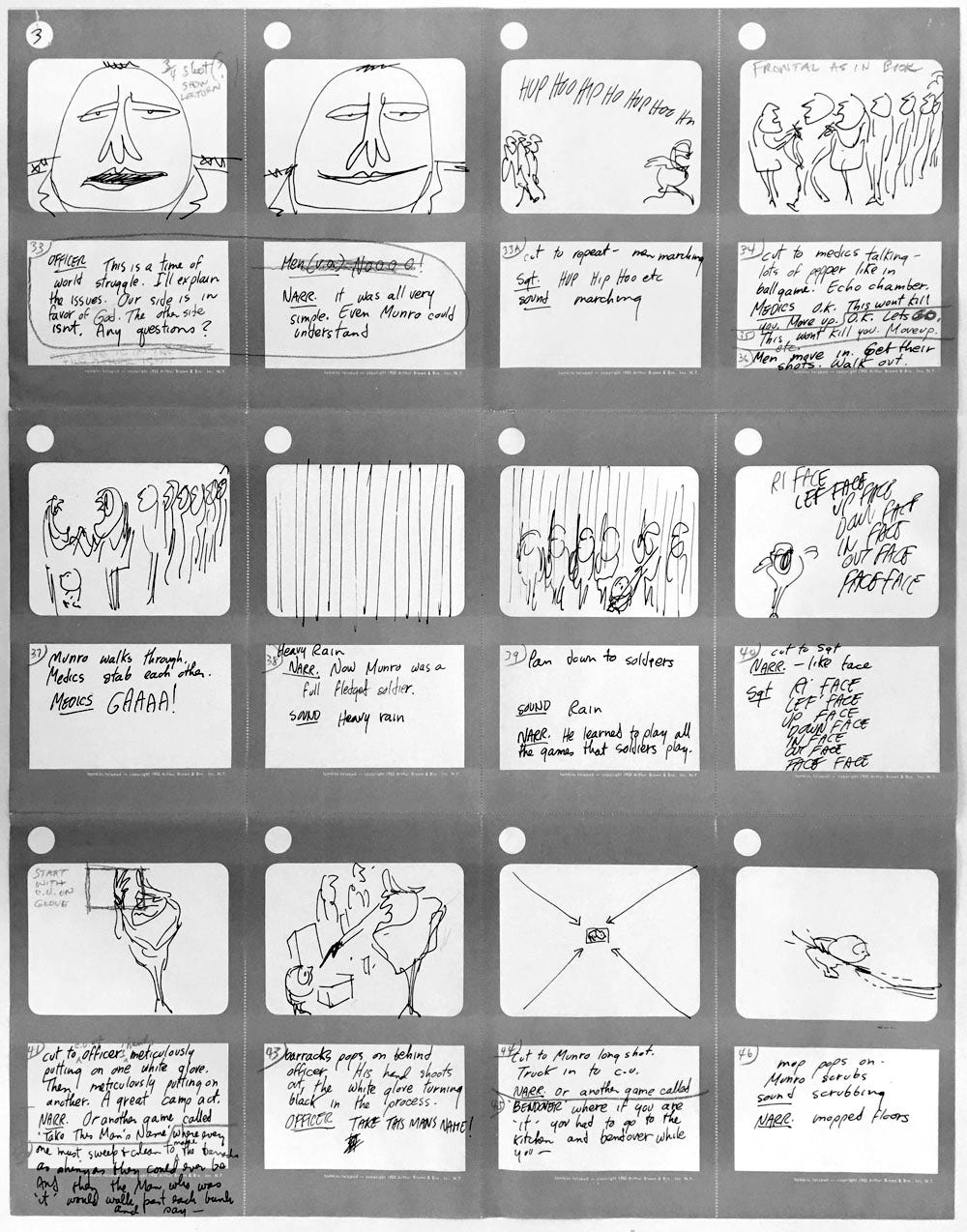

By this point, Feiffer was growing famous for his print cartoons, and Deitch was taken with his early Munro project. “I was able to contract the film rights for my studio, where I expected that staffer Al Kouzel would direct,” Deitch wrote. Pre-production began: Feiffer and Kouzel, another former Terrytoons newcomer, developed the idea. Feiffer wrote and storyboarded it.

“I was very close to being able to get this into production,” Deitch said. “All I needed was the money.”

That, though, was easier said than done. Deitch’s studio was awash in TV ads and other commercial jobs, but it couldn’t find funding for Munro. The storyboards stayed pinned to the studio wall. Deitch, a master of hyperbole, liked to say that they were “almost getting brown with decay waiting for somebody to come in and back it.”

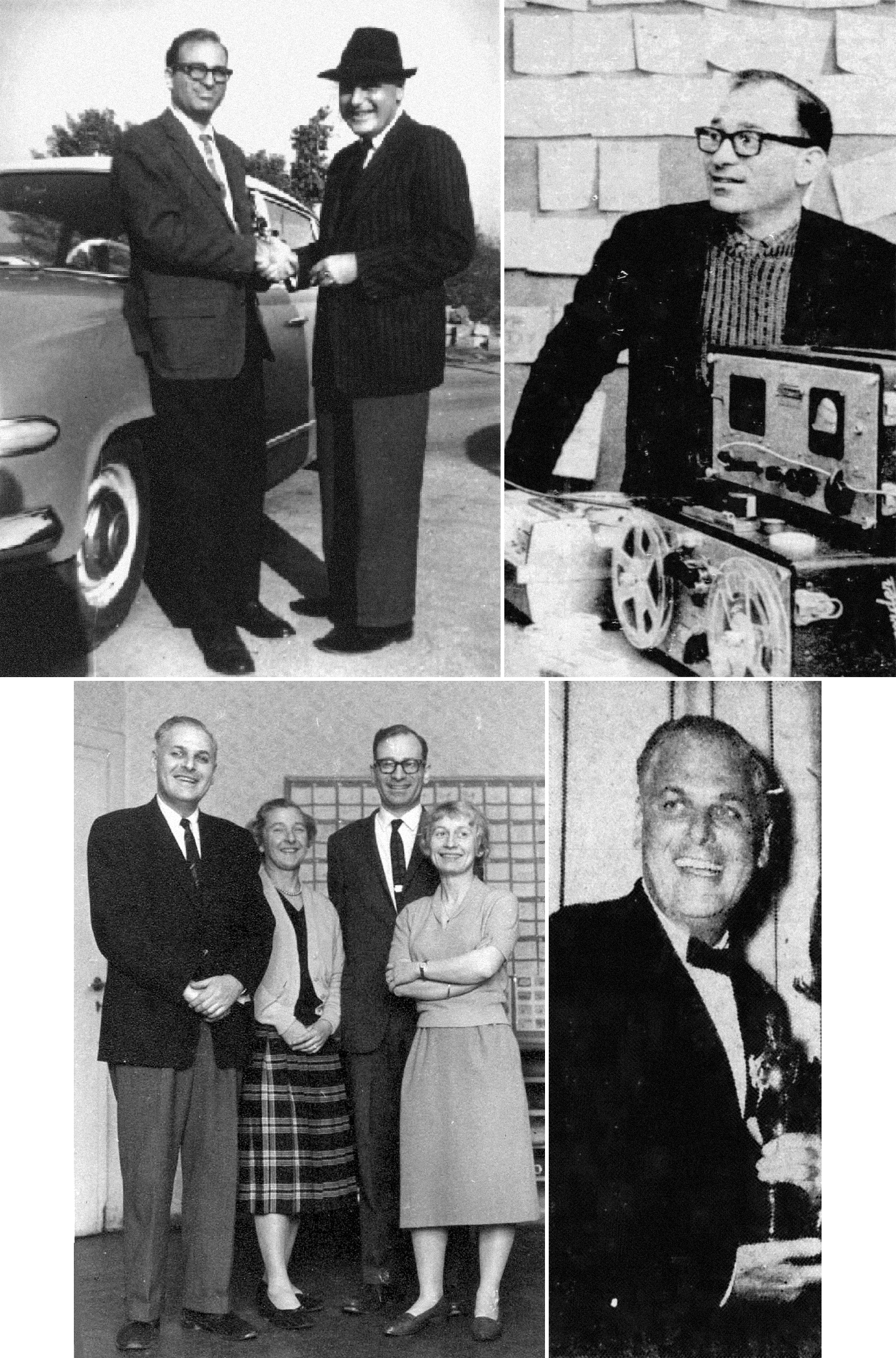

Finally, in 1959, someone did come in — a producer named William L. Snyder. As Deitch recalled:

He was 40 years old; prematurely gray, wore a striped seersucker suit and expelled paralyzing clouds of smoke from his contraband Cuban cigars. His most penetrating features were his Paul Newman-blue eyes. He was a man who could talk anybody into anything, as I was soon to find out. He exuded confidence, enthusiasm and charm. He referred to himself as “beautiful,” and considered himself irresistible, and a mover.2

Snyder had a few cartoons in production that he wanted Deitch to touch up. The problem was that they were being made in Prague, Czechoslovakia. To Deitch, this sounded insane. “Isn’t that one of those communist countries?” he remembered asking. Snyder told him that it was strictly business, but Deitch was having none of it and “kept throwing him out.” This went on for several visits.

Even so, Snyder ultimately wore him down with a deal: check out the Prague studio for ten days, and he would back this Munro project on Deitch’s wall.3 In that moment, Deitch was just desperate enough to give it a shot.

Bill Snyder wasn’t trustworthy, but he also wasn’t lying — this time. “My two oldest sons thought he was a con man,” Deitch recalled. This was at least half-correct.

Yet Snyder really did have connections in Prague. He’d gotten involved with it in 1949, thanks to a private showing of Jiří Trnka’s puppet film The Emperor’s Nightingale in New York. “It was the most amazing animated movie I’d ever seen,” Snyder said. He went to Prague, got the rights, added narration and released the film in the States — successfully.4 It turned out that American money could penetrate the Iron Curtain.

So, Snyder worked with the Czechs during the late ‘50s to set up his own animation unit at the state-run Krátký Film in Prague. The initial pull, he admitted, was “cost savings.” Czechoslovakia had talented artists, and American dollars were like gold there. Snyder wanted to exploit the exchange rate to get great films for cheap. But his love for Czech animation was genuine: he named his first child, a daughter, “Trinka.”5

In October 1959, Deitch flew to Prague and found himself in an unknown world.

Almost no one in Krátký Film’s animation studios spoke English — and not everyone was amused to have an American overseer. These were skilled, seasoned teams. Snyder’s production manager, Zdeňka Najmanová, knew English but refused to meet with or speak to Deitch for some time. Snyder’s main director, Václav Bedřich, was a veteran with “his own idea of what films should look like.”

Nevertheless, Deitch went ahead with the plan, relying on an interpreter named Lulka Kopečná. He pitched Munro to the Czechs. As Deitch recalled:

... the first thing I had to do was to get across to the animators, there at the studio, my Munro storyboard. I had it on the wall, hanging up there. I’m gesturing, telling all the jokes, and each time I come to a gag line, I had to wait. And then [Lulka] translated it, and then they laughed. [...] It’s like an out-of-sync movie. The laughs were coming about 15–20 seconds after I told them.6

Deitch played the team reels of work he’d done at UPA, too. “I needed to show them that I was really a professional, and that my advice was worth listening to,” he wrote. “After that, I seemed to get increased respect, and was no longer viewed as a troublemaking interloper.” Within a few weeks, even production manager Najmanová warmed up to him.

So, Deitch got to work. He put Munro into production, alongside another pet project called Samson Scrap, while tweaking and managing Snyder’s films. What quickly grew clear was that the Czechs weren’t working with the tools he knew — they’d invented their own animation process with the limited resources they had. He remembered:

On my first trip [there], they showed me a whole bunch of their films, and they showed me their equipment. And I look at the equipment, and I looked at the films, and I figured, “These guys must have talent!” Because they had the most primitive, crudest type of animation cameras. I mean, they moved drawings around on a pantograph. They had what I would call a yardstick that they slid the pans on. They didn’t even have movable pan bars, or a movable compound, or any of the things we thought were essential. They had two pegs instead of three pegs [on their peg bars] — impossible to find the center of your field! They had a camera field... the biggest field was number one, and the smallest field was number fifteen, actually the opposite direction that we were used to in the Oxberry system.

The Czechs had developed a local style of animation, different from the American one. “We still didn’t use dialogues and special sound effects at that time. We didn’t know much about the lip sync either,” said Najmanová. In fact, Deitch wrote, the Czechs didn’t even rely on exposure sheets to plan and structure their animation.

As a result, Munro would be a weird hybrid of American and Czech cartoons. Both sensibilities are tangled up in it.

Deitch screened films from home and lectured on their techniques. Some of the Czech artists became his disciples. “Deitch taught us the details on which an animated film is based; he was great at it,” recalled Zdeněk Smetana, an animator on Munro. Another close colleague was Munro animator Milan Klikar — Deitch wrote that he was “quickly interested to work with me, wanting to adapt to the American style.”

In the coming months, Deitch learned that his status as an American made him stand out in a positive way. Many Czechs at the studio — many Czechs in general — hated the state of things and imagined America as a paradise. “They all wanted to talk to me about America, how perfect our country must be, and about how terrible it was in Czechoslovakia,” Deitch wrote. He stuck up for their country more often than they did.

Deitch set up an international pipeline for Munro and the other films, flying back and forth to New York. He relied on the airborne shipping used by Czechoslovak Filmexport. “I arranged for Zdeňka to send me the 35 mm film tests of the pencil animation scenes,” he wrote. “I would then edit them together on the Moviola viewing machine in my New York studio, and send back my comments and orders for revisions.”

In New York, Al Kouzel drew Munro’s layouts. The voices were done there, too, with Deitch’s son Seth as Munro and actor Howard Morris as nearly every other character. One exception was the screaming sergeant — voiced by Jules Feiffer.

Meanwhile, Deitch recorded the music in Czechoslovakia. It was composed by Štěpán Koníček, who conducted an orchestra of 35 players as Deitch captured the audio on a small, portable, reel-to-reel tape recorder he’d brought from America.7

All of this international travel wasn’t missed by the American press — especially once Snyder started to secure outsourcing deals with major stateside clients. He regularly spoke to journalists, although he didn’t tell them the whole truth about what was happening.

As Snyder got contracts in 1960 to animate Tom and Jerry and Popeye cartoons in Czechoslovakia, the press printed his wild stories about an animation network spread across Western Europe. When Deitch’s Samson Scrap was signed in America during mid-1960, The Hollywood Reporter told readers, “Storyboard and tracks will be done here and the animation in Europe, principally in Zurich and Milan. Snyder and Deitch left for Zurich over the weekend.” Around the same time, Variety repeated the Zurich and Milan story, and added that Snyder was hoping to expand to London.8

By 1961, there were claims that both London and Rome were part of Snyder’s faraway, exotic-sounding group of partners. A rare one or two stories named “Prague” as a fifth city on the list, without elaborating where it was.9 Deitch recalled that Snyder didn’t mention Czechoslovakia to him during their first negotiations, either:

In his effort to lure me to his service, Snyder never referred to his animation facilities as being in “Czechoslovakia.” Czech-o-slo-va-ki-a was a distant country with an extremely foreign, six-syllable name, difficult for Americans to pronounce. But its capital city, “Prague,” had a one-syllable name, spelled and pronounced exactly as the French and British spell and pronounce it, thus having a vaguely romantic and less sinister ring to it.

On Munro, Snyder left the Czech studio and artists uncredited. There were five animators, an animation director (Václav Bedřich), a background painter (Bohumil Šiška) and many more, as Deitch later detailed on his blog. But only Americans appeared in the credits, alongside the name of Snyder’s own distribution company: Rembrandt Films.

Snyder knew he was skating on thin political ice and was “terrified” that his scheme would be publicly exposed, Deitch said. Many were left clueless. Jules Feiffer himself told the press decades later, “I suppose I was dimly aware it was made in Czechoslovakia, but I had no active participation in the making of Munro.” True or not, he wasn’t talking.

Even so, Snyder didn’t shy away from publicity with this film. By 1960, he had the idea that Munro could get an Oscar nomination.

The Czechs raced to finish the project in time for a qualifying screening in Los Angeles. When the film laboratory in Barrandov accidentally destroyed Munro’s negative at the last minute, everything had to be reshot. As Najmanová said:

... it was a horror! I cried when I came to the lab. So there was a rumor after that about me being the first producer they ever saw crying over the destroyed film. But everything was at stake for us. So we were reshooting the film for two nights and one day.

Najmanová and camerawoman Zdenka Hajdová worked on the reshoot together. The film was reedited and reassembled, then immediately shipped to America via Czechoslovak Filmexport. “Snyder had it in hand on the very last possible day, got it into a previously arranged theater and it qualified!” Deitch wrote.

Munro ultimately got its nomination. Not only that — it won the Oscar for animated shorts in February 1961. The downside was that Snyder entered the film under his name and collected the Oscar himself. “Next to the day I got married, getting an Oscar for Munro was the best and most exciting day of my life!” he told the press at the time.10 Snyder kept the statuette, engraved with his name. Deitch was livid.

But things could’ve been worse. Deitch was now at home in the Czech animation scene, becoming friends with people like Jiří Trnka. And Deitch and Najmanová were falling in love — they married in 1964, remaining together for the rest of their lives. They kept working for Snyder and other American clients for decades.

Then there was Munro itself: a hilarious, piercing, great-looking film. It’s still one of the best cartoons ever to win an Oscar. The team did full justice to Feiffer’s design and original story — the Czech animators nailed the style. Munro got a wide release in America, screening in front of Breakfast at Tiffany’s and going down as a classic.

Deitch had done something here, and it was the start of many good things to come. As the Czech historian Jan Poš later wrote, “Deitch’s collaboration with the Czech animated film industry is a wonderful example of the benefits of international cultural exchange.”11 Whatever the bumps and compromises (and there were a lot), things had turned out. Munro had crossed all borders, making possible what realistically never should have been.

2: Newsbits

Russian animator Sasha Svirsky made his brilliant My Galactic Twin Galaction (2020) free on Vimeo. But with a change: a red dot at the start, where the logo of the Ministry of Culture (which helped to fund the film) used to be. “We don’t want to spread this criminal sign anymore,” Svirsky writes. Animation scholar Pavel Shvedov calls the move “extremely bold and even somewhat radical.”

On a similar note, Russia’s Alexander Sokurov gave Forbes Russia a fiery interview, accusing the state of suppressing art and culture at a greater scale than in Soviet times. The director, who recently made the surreal collage feature Fairytale, frequently saw his work banned in the USSR.

An Italian animated doc, Tufo, tells the story of Ignazio Cutrò. He served in the 2000s as a testimone di giustizia, an innocent victim who testifies against the mafia (at serious personal risk). It’s competing at Annecy this year. See the trailer here.

Continuing its tradition in England, Magic Light Pictures has a new Christmas special lined up for 2023. This one adapts the children’s book Tabby McTat.

In Japan, the rise of franchise films continues. The latest Detective Conan feature, Black Iron Submarine, is reportedly the 26th in the series — but the first to pass 10 billion yen (around $73.6 million).

The vice president of Nigeria attended and praised the premiere screening of Gammy and the Living Things, a homegrown animated feature that’s been in production for years at Utricle Studios in Lagos.

In Canada, animator Michel Gagné shared a quick look at the feature film he’s been creating essentially by himself for the last decade: The Saga of Rex. He writes that it’s now 73% complete.

On a related note, Canadian solo-feature-animator Denver Jackson spoke with Cartoon Brew about his viral Kickstarter success The Worlds Divide. He offered strategies for surviving the long hours. “Every day I’ll go jogging now and do jumping jacks just to get the blood flowing,” he said.

Lastly, we looked into the stories of three excellent Hungarian films from the ‘60s and ‘70s: Sisyphus by Marcell Jankovics, the gingerbread-based Honeymation and the wild, intense Kidnapping of the Sun and Moon.

Until next time!

The location and foundation date for Gene Deitch Associates come from Motion Picture Daily (August 14, 1958) and Business Screen Magazine (February 27, 1959). Meanwhile, the date for Deitch joining Terrytoons is sourced from Broadcasting-Telecasting (July 2, 1956).

From Deitch’s book For the Love of Prague. That and a documentary about him, For the Love of Prague (2006), supplied the quotes used directly after this. We refer to both the book and documentary throughout — you can find the latter embedded on Deitch’s blog.

Alongside Samson Scrap, which was likewise wasting away on the wall of Gene Deitch Associates. It was made in Prague, too. Cartoon Research once posted the film with details from Deitch.

Snyder’s experience with The Emperor’s Nightingale is recounted in The Baltimore Sun (November 25, 1951) and The Evening Sun (November 7, 1951).

Snyder told Variety (July 6, 1960) about his initial goal of saving money, but claimed that production was “no longer less expensive” by then. Given that Snyder reportedly made Tom and Jerry cartoons for half their American cost at the time, this is questionable. Also, Snyder’s daughter Trinka was mentioned in The Daily Times (March 16, 1956) — Trinka was the standard American pronunciation of Jiří Trnka’s last name.

Deitch says this in a recorded interview with Kopečná, embedded on his blog. His quote about Václav Bedřich comes from this Czech interview.

From Deitch’s blog. He wrote about the voice recording here.

From Variety (July 6, 1960) and The Hollywood Reporter (July 6, 1960). The detail that Snyder signed Tom and Jerry in 1960 comes from Variety (March 15, 1961).

After Munro won the Oscar in February 1961, a few stories in Variety made passing mention of Prague as part of Snyder’s supposed European studio network: “London, Zurich, Milan, Rome and Prague.” We’ve seen no evidence that these other teams existed. From April 26, 1961, and May 24, 1961.

From The Daily Item (October 27, 1961).

From Krátký Film: The Art of Czechoslovak Animation.

Always interesting how things get developed, funded and made the whole process is fascinating. Thanks for sharing this. It was so easy to read and flows so well.