Animating by Candlelight

Plus: animation news.

Happy Sunday! It’s time for another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and this is our lineup:

1️⃣ Animation after the fall of the Soviet Union.

2️⃣ Newsbits in animation from around the world.

For those just finding out about the newsletter — it’s free to sign up to receive our Sunday issues every week:

With that, here we go!

1 – The aftermath

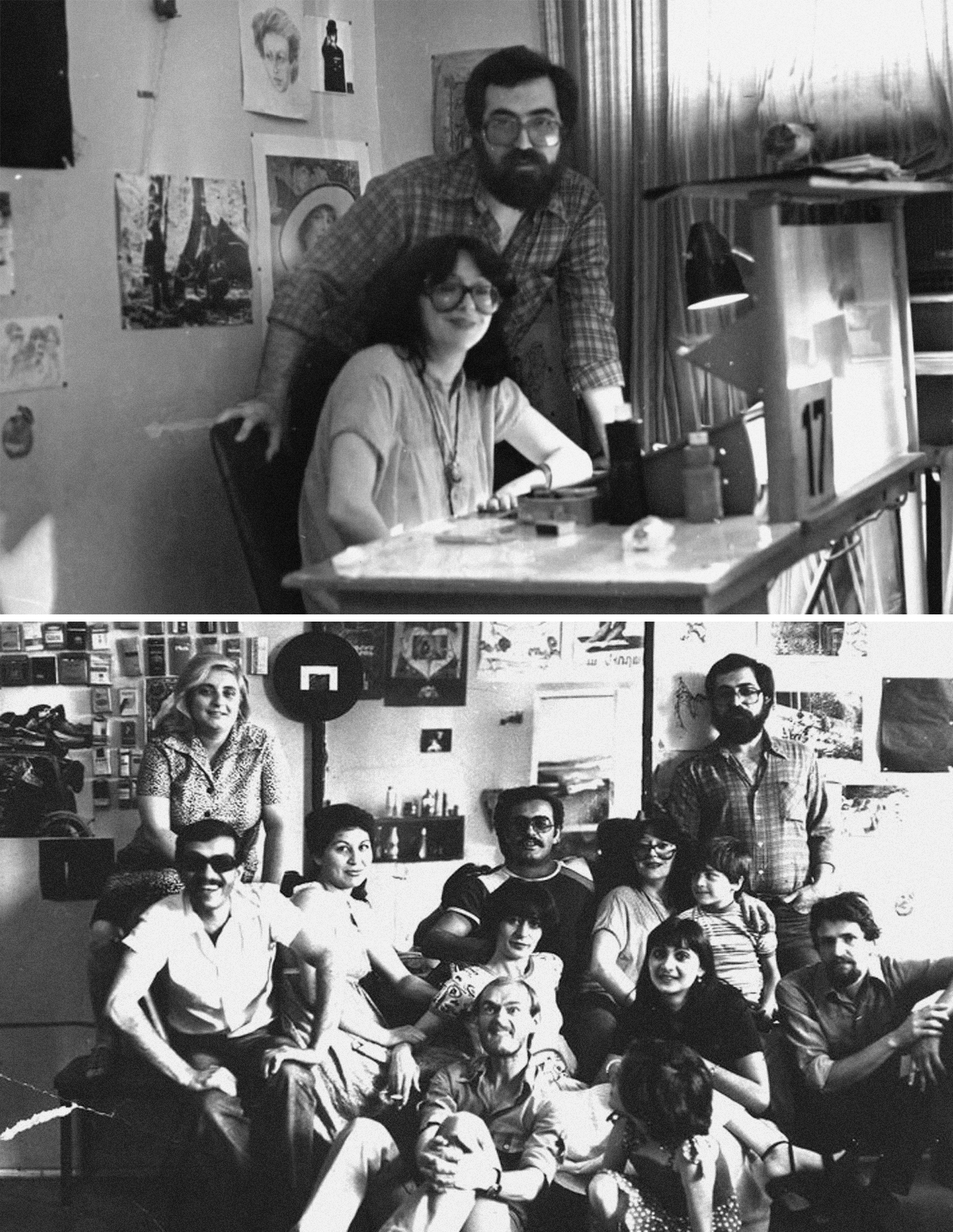

In a recent issue for members, we wrote about Robert Sahakyants — the most famous animator ever to emerge from Armenia. He rose in the ‘70s and ‘80s, when his country was under the control of the Soviet Union. And he was a rebel.

Sahakyants was a so-called “Soviet hippie.” He listened to illegal Beatles bootlegs etched onto X-rays. He fought bitterly against the censors and bureaucrats in Soviet Armenia. His best-known cartoons, like Wow, a Talking Fish! (1983), are surreal, psychedelic and a bit subversive.1

As the USSR weakened in the late ‘80s, Sahakyants turned his art into an open political attack against the system. He felt the need to act when, as he said, “millions of lives hung on life-and-death decisions made by some bastard sitting in Moscow.”2

In 1991, Armenia gained its independence. The Soviet Union, the world’s largest empire at that time, ceased to exist. Sahakyants and his fellow animators were freed from the censorship, the blacklists and the state meddling they’d found so suffocating. But what was waiting on the other side of Soviet control wasn’t what they’d expected.

A whole social and economic order had fallen apart almost overnight — chaos came to Armenia. State funding and support for animation, which had created Armenia’s animation scene, evaporated. A yearslong energy shortage left artists to create in the cold and the dark during winter.

On Sahakyants’s films The Axe (1994) and Elections (1994), conditions were extreme. “I worked by candlelight then. I knew which candles burned better (Volgograd ones were better than the others),” he said of Elections. Soon after The Axe began in the early ‘90s, Sahakyants lost his studio’s backing and struggled to find help in the private sector:

We scrambled and scrambled and found a person who agreed to finance it. The film began. He didn’t continue financing it either. A third producer appears who’s willing to put money down on it. He bought the cels and stopped there. For four years I’ve been trying to make this film!

In the meantime, The Axe’s production materials kept getting destroyed. As Sahakyants said:

I had to start over the film The Axe four times because the cels on which we made it back then… we didn’t have time to finish [the film], and in the winter [the cels] simply froze, the paint crumbled. There was nowhere to store them because the temperature in the apartments reached 4 degrees [Celsius].

Armenian animation had been owned and funded by the communist system — which had supplied the artists with facilities, equipment, training and distribution. Now, Sahakyants and his team were adrift in a newly unstable, newly capitalist country. Asked in the 2000s whether his Soviet-era films could’ve been made in post-Soviet Armenia, Sahakyants replied, “No, just as it is in the entire CIS territory.”

He was always defiant about it — freedom from the Soviet Union was worth it to him. He was willing to accept the challenge of surviving and creating in the new Armenia. But he was realistic about the tradeoffs. Even when he died in 2009, Armenia’s animation industry hadn’t truly rebounded.

The Soviet animation community had long viewed the censors and authorities as their enemies. It was a huge, opaque, dysfunctional bureaucracy, always at their throats. “We had to fight against the officials. And this was only possible together,” explained Russian director Fyodor Khitruk (Winnie-the-Pooh). “I’m afraid that the community was based on opposing a common enemy. We, by the way, were fed by this enemy. But we knew what we were fighting for and against.”

There was no love lost between these artists and the USSR. At the same time, their whole industry and livelihood now risked vanishing across the post-Soviet landscape. Every country experienced it a little differently, but artists had no choice other than to adapt, quickly, to life under capitalism.

One of them was animator Priit Pärn (Breakfast on the Grass) of Estonia. Like Sahakyants, he was a paradox: a USSR-funded artist who’d battled the authorities and made openly anti-USSR art. His career was a product of the old system’s absurdity.3 Even so, it didn’t take him long to realize that he wasn’t a fan of capitalism, either.

Speaking about the situation in 2001, Pärn said:

In the Soviet time everything which was not permitted was forbidden. So there were an endless number of restrictions that were political, but just insane. Now all the limits are connected with money. The final result is very often the same as before, sometimes worse.

In Russia, animator Yuri Norstein (Hedgehog in the Fog) has made even harsher comments about the market economy. “I hate capitalism as a system, as a structure, as a mode of thought, as a market,” he said in 2016.

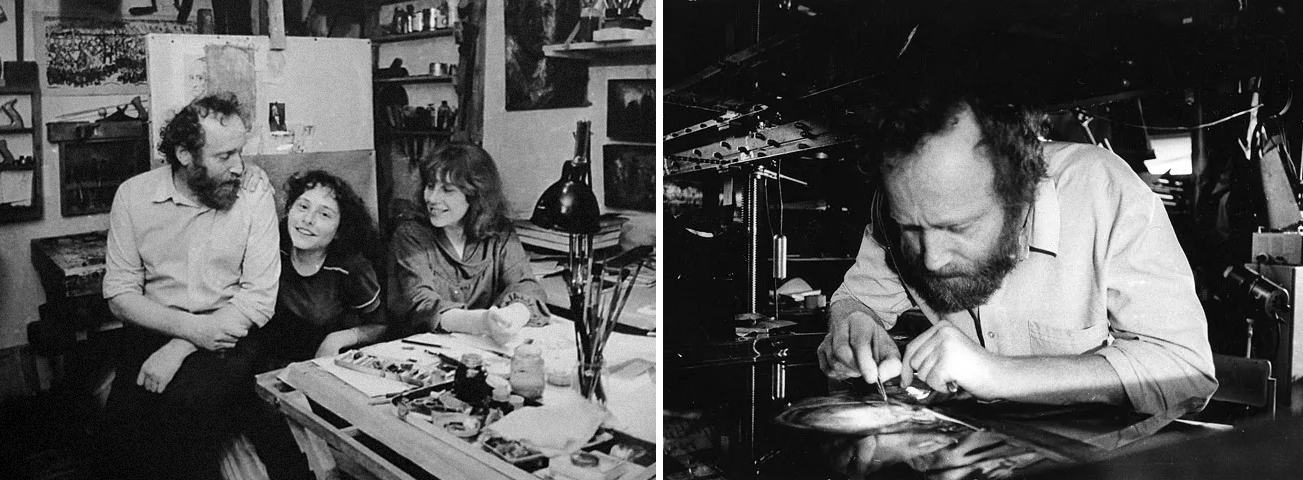

Working in Moscow at the state-owned studio Soyuzmultfilm, Norstein was put through the bureaucratic wringer over Tale of Tales (1979), a masterpiece that he and his wife Francheska Yarbusova created. It was almost banned outright. Norstein had hated that system, and for good reason. But his hatred for capitalism is stronger:

When I’m asked when it was better to work, I say that it was in Soviet times. ... I didn’t think about whether I had enough money or not. And now I must think all the time about where I’ll spend and where I’ll earn. In the USSR they didn’t give money to individuals — they gave it to the studio, there was a plan, a set number of films, and among them a masterpiece could appear.4

These feelings didn’t spring from sheer nostalgia. Soyuzmultfilm was hit hard by the fall of communism. In the 1990s, efforts to privatize the studio led to the appointment of Sergei Skulyabin as its head. He was an embezzler and a gangster who enriched himself by selling (and outright stealing) the studio’s archives and film rights. Those who stood against him were often beaten by his henchmen.5

Even after Skulyabin was removed, Soyuzmultfilm withered for many years. And Russian animation, starved of the full state funding that had established it, struggled.

Norstein himself has released little animation since the Soviet era. He’s done a few commercials for Russkiy Sakhar, an opening and ending sequence for a children’s TV show, a scene in Winter Days (2003). Meanwhile, he and Yarbusova have tried for over four decades to finish The Overcoat, their stop-motion magnum opus. It hasn’t been four decades of continuous work. They didn’t have that luxury.

“I started shooting The Overcoat in 1981,” Norstein said in 2009, “but over these decades I’ve managed to devote only two years to it. The rest of that time was spent fighting for survival.”

Armenia, Russia and Estonia were all part of the USSR, but the Soviet zone of influence extended to other communist countries (the “satellite states”) that weren’t strictly members. One was Czechoslovakia, divided today into Slovakia and the Czech Republic. Maybe no country behind the Iron Curtain had a greater animation scene. It brought the world Jiří Trnka, Hermína Týrlová and more.

Jiří Barta is another hero from that scene. He made The Pied Piper (1986), a dark, macabre stop-motion gem. To do it, he had to outwit the bureaucrat who oversaw his studio, a notorious man who was at one time a high-ranking member of the state secret police. Barta was playing with fire — but he got away with it.6

Unlike Norstein, Barta has released large-scale work under capitalism, too. The biggest is Toys in the Attic (2009), a stop-motion feature that repurposes junk in an attic as the basis for a whimsical adventure story. Its villain is a bust who rules the “Land of Evil” on one side of the room. The bust doesn’t self-describe as a communist, but it doesn’t have to: it clearly represents the old regime.

Nevertheless, creating Toys in the Attic brought Barta into collision with the free market. He’d faced the bureaucracy — now he faced its replacement. When an interviewer told him that the new world seemed harder for animators, Barta answered:

I probably shouldn’t say this, but that’s how it really is, because political censorship can always be circumvented. There was persecution back then, but the animated language often isn’t spoken very clearly; it’s more about metaphors and symbols. And besides, everyone took the animated film as something merely for children, where it doesn’t matter so much. Financial censorship didn’t exist in those days — we didn’t care who the film was for, where it would be screened or whether 10 people or 50,000 would come to see it, which are precisely the questions that matter most now. Today, the main concern is that it’s done quickly and cheaply.7

Elsewhere, the producer of Toys in the Attic regretfully admitted that they “could not provide the creators with such conditions as they had, for example, in the era of socialism.” The film’s assistant director, who’d also worked on The Pied Piper, went into greater detail:

The Pied Piper ... was created in the fully professional conditions and capabilities that were present in the Jiří Trnka Studio — all means of production were available. … From the perspective of today and in hindsight, it was a walk in the park compared to Attic. The film Toys in the Attic is not only longer than The Pied Piper ... but much more demanding in terms of work. Moreover, it was filmed in very difficult conditions that even the worst skeptic couldn’t have dreamed of. Actually, we had to completely set up all the facilities, workshops and warehouses, and in particular train new collaborators.8

It bears repeating that the horrors of the USSR were very real. The Stalin years brought the worst of them, but no era was immune. Even animators, maybe the most insulated class of artist in the Union, had to deal with its problems. In Russia, Andrei Khrzhanovsky crossed the line with Glass Harmonica (1968) and found himself drafted into the Navy for two years as punishment.

It’s not for nothing that Sahakyants, who suffered more than most animators in the post-Soviet era, preferred animating by candlelight. As he said, “I can be accused of anything, but not of sympathizing with the communists.”

At the same time, all of these artists (maybe Sahakyants most of all) had their careers made by the old system. The state controlled animation, but also supported it. People like Norstein were never built for capitalism. Hedgehog in the Fog wouldn’t exist if the Soviet government hadn’t given Soyuzmultfilm the means to produce it. The new kind of censorship — “financial censorship,” as Barta put it — oppresses more quietly, but often no less.

There aren’t any easy answers here. For people in animation, the Soviet Union was neither a creative wasteland nor a utopia. Its disappearance was seen by certain artists as a gift and by others as a disaster. In some sense, both were right.

But what’s clear is that the post-Soviet countries whose animation scenes have bounced back are the ones that haven’t forgotten the good ideas of the USSR. Renewed state support for artists has given Estonia, for one, a thriving animation community today.

A couple of years ago, the great Estonian film Sierra (2022) toured the world and made the Oscar shortlist. Its director, Sander Joon, said this in an interview:

Many thanks to the Estonian Film Institute and the Cultural Endowment of Estonia! It is good that we have a funding system and that animation is supported. If you think about our American colleagues, there is absolutely no such state support in the USA. You could complain that it was very difficult, but at the same time you have to understand that it’s a great privilege that we can make our own films here in Estonia.9

2 – Newsbits

The Japanese team behind Hidari (the stop-motion samurai film) is back in the studio — and livestreaming its animation process on YouTube. An unprecedented look behind the scenes of puppet animation.

In America, Lauren Faust and Craig McCracken are writing the script for an animated feature called The Circus Ship.

Check out the pitch pilot for Children of the Wind Mother, a Hungarian feature film in development. It’s being compared to Ghibli’s work, but there’s a lot of Hungarian folk art and Cartoon Saloon mixed in. One to watch.

Aya Marzouk of Egypt directed a short about South African apartheid, released a few months ago. Scholar Thula Simpson, its writer, just spoke about its creation.

It might be the end for the American film Coyote vs. Acme, reportedly slated for deletion as another Warner tax write-off. “Whatever the technical legality of writing off completed films and destroying them for pennies on the dollar,” writes Matthew Zoller Seitz, “it’s morally reprehensible.”

Also in America, Disney has reworked its Moana series into a full-fledged sequel.

Soyuzmultfilm’s CEO (Boris Mashkovtsev) is worried about the lack of teen-focused animation being made in Russia. Preschool cartoons are crowded, and there are fewer young children today. By contrast, he says, Japanese anime has “learned to talk to teenagers about topics that interest them” in ways that reach them.

American showrunner Vivienne Medrano gave an in-depth interview to Cartoon Brew about the process of indie animation, what she’s learned and more.

One more American story: the pilot animatic for Before Courage (2020), a canceled prequel to Courage the Cowardly Dog, is now online.

In Spain, Robot Dreams won for adapted screenplay and in the animated feature category at the Goya Awards.

Lastly, we told the story of the 1990 Oscars in animation. A pair of beginners beat the paint animator Alexander Petrov (The Old Man and the Sea) with a homemade film — and he nearly abandoned his career in response.

See you again soon!

We’ve linked Wow, a Talking Fish! and several other films mentioned today to Animatsiya, a small site run by the veteran translator Niffiwan. It catalogues Eastern European animation and (legally) overlays subtitles onto YouTube and Vimeo embeds, making this work more accessible than it’s ever been.

Sahakyants said this in Armenian International Magazine (March 1994). The later quote about his cels freezing comes from Interview with Robert Sahakyants (2001).

Pärn’s animation career had a rocky start. His film Is the Earth Round? (1977) was received poorly by the main censor board in Moscow, Goskino. As writer Andreas Trossek noted, Goskino banned the film from screening outside Estonia. Pärn recovered in part due to a lucky break with his second cartoon, … And Plays Tricks (1979), which won a prize in Bulgaria. The dysfunction of the USSR’s bureaucracy worked in his favor, as getting an award changed his status on the books. Here’s scholar Mari Laaniste:

According to Pärn’s account, the film was only meant to be screened outside of competition, but actually ended up winning an award at the festival, which did not please Goskino, because this meant Pärn had officially become an “award-winning filmmaker,” thus more difficult to control than an annoying beginner.

Norstein said this in a 2016 interview with Afisha Daily.

See the chapter “Animating the Past” in the book Blockbuster History in the New Russia: Movies, Memory and Patriotism.

We told this story in our issue on The Pied Piper early last year. Another English account of the events was released later in 2023 as part of Deaf Crocodile’s Blu-ray.

From Barta’s 2009 interview with Hospodářské noviny, archived here. As always, Wayback Machine links may be broken if clicked in email, but they work fine on the website.

This quote and the one from the producer come from the press kit for Toys in the Attic, archived here.

Joon made this comment in this interview.

Fair article. Soviet (and soviet-adjacent) animation is bound to these contradictions that in a way defined its greatness by pushing the limits of the animators within a (somewhat) safe framework. Although Russian animators emigrating to other parts of the world is increasingly more common, their native country has gifted them a massive pool of references to develop their own style and an interest in the artform in the first place, whatever the conundrums said legacy was created under were.

A country that seemed to thrive somewhat after the dissolution of the USSR is Belarus. Some beautiful, quaint films were made there during the 90s, such as the work of Vladimir and Yelena Petkevich or Yuletide Stories by Irina Kodyukova, in my opinion the most aesthetically beautiful cutout film since Norstein's.