Animation at Its Most Pretentious

Plus: global animation news and Studio Ghibli commercials.

Welcome back! We’re here with more from the Animation Obsessive newsletter. This is what we’re doing today:

1 — the Oscar-winning film The Critic (1963).

2 — animation news items worldwide.

3 — retro ads by Studio Ghibli.

New here? We publish every Sunday and Thursday. It’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues — get them in your inbox every weekend:

With that out of the way, here we go!

1. “What the hell is this?”

The Critic debuted in theaters almost 60 years ago, but it still makes the rounds online. And it’s easy to see why. The cartoon is three-and-a-half minutes of abstract visuals — with Mel Brooks complaining over them, bitterly.

The appeal of The Critic is evergreen. Brooks plays a 71-year-old moviegoer named Murray — who loudly reminds himself (and everyone else in the theater) that he paid $2 to see this “junk.” The images running across the screen never amount to much. Brooks riffs, trying to make sense of them. “I don’t know much about psychoanalysis,” he concludes, “but I’d say this is a dirty picture.”

The film won the Oscar for animation in 1964, and its jokes land even today. The Critic feels so effortlessly funny, in fact, that it’s easy to miss how sophisticated it really is. Behind the scenes, it took at least a year to create — and it came from one of America’s smartest animation directors at the time.

That director was Ernest Pintoff, a member of the New York animation scene. He was a jazz musician who’d studied art in college. He was cool — and known to speak in hip, mumbled slang. Per one historian, he was “considered the leader in the intellectual cartoon for the American art houses featuring foreign films” during the early ‘60s.1

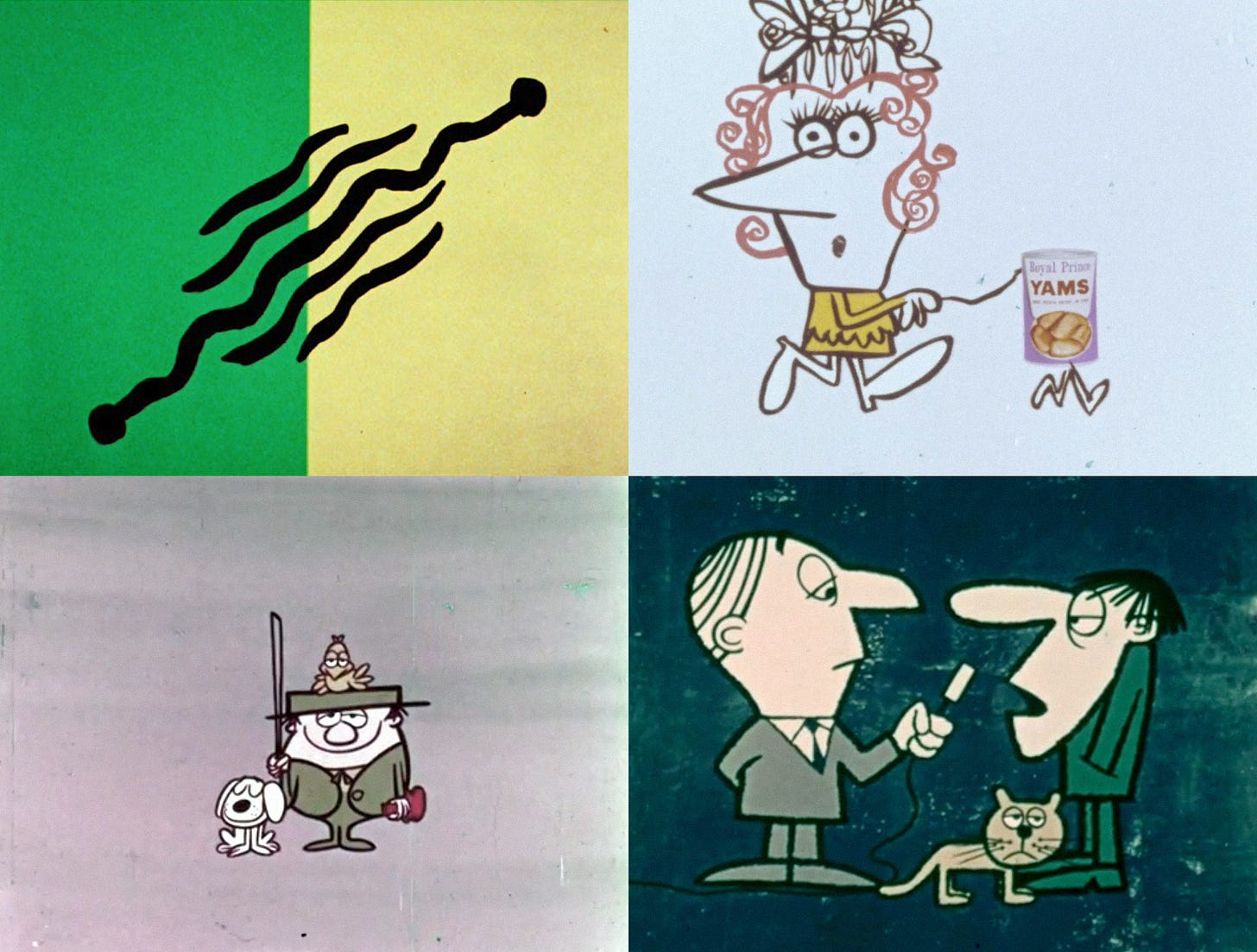

In plain English, Pintoff made independent animation. He funded it himself, using money he earned from his popular animated TV commercials. Without Hollywood backing, Pintoff had to hustle at first — “I promoted all my films independently, through screenings at various New York City movie theaters,” he wrote.

The Pintoff style was modern, slick, minimal and clever. He’d started developing it at UPA, where he played a key part on The Boing Boing Show. His stint at Terrytoons produced the groundbreaking Flebus (1957), which refined his sensibility even further.

By the time he went independent, Pintoff stood out. Films like The Interview (1960) are unmistakably his work: a great concept matched with funny, wordy dialogue — and very little animation. “It put all of my ideas into the soundtrack and became known for that,” he said of his style. Which is how he got to The Critic.

Mel Brooks met Pintoff through comedian Carl Reiner, who’d voiced Pintoff’s film The Violinist (1959). They became friends. Brooks recalled Pintoff as “a brilliant guy, a cartoonist and sweet as sugar.” (Despite his hipness, Pintoff was known for his modesty, “preferring to talk about anything but himself and his work.”2)

In 1962, Brooks gave Pintoff the spark of the idea for The Critic. As The New Yorker reported:

One evening in the spring of 1962, Brooks was sitting in a Manhattan movie theater watching a dazzling abstract cartoon by the Canadian animator Norman McLaren. “Three rows behind me,” he recalls, “there was an old immigrant man mumbling to himself. He was very unhappy, because he was waiting for a storyline and he wasn’t getting one.”

“Mel was amused by the idea and told me about it,” Pintoff remembered, “and I liked it. I could identify with the reactions.”

As an abstract painter and an expert at self-deprecation, Pintoff was drawn to the idea of doing a film based on Brooks’ encounter. A film about “the average artist’s ability to communicate with people.”3 So, Brooks and Pintoff decided to make The Critic.

Their film would become, in many ways, a satire of the very thing that it is: a smart, independently-minded cartoon for adults.

By this point, the traditional studio system for theatrical cartoons was dying — the Oscars for animation from 1960 through 1964 went to “individual artists in complete control of every phase” of production, according to historian Ronald Holloway. The Critic jokes about films like these, but it also happens to be one of them.

Pintoff’s cameraman Bob Heath laid the groundwork for the film, putting together the visuals. The work of abstract animators like McLaren can be ingenious — Heath’s purposely wasn’t. Here’s Animation Magazine:

Bob Heath was asked to create visuals composed of what Pintoff considered to be “pretentious” abstract forms. Pintoff says that Heath “improvised, by doing things like dripping paint and using Q-Tips. I told him to create anything he wanted. Heath was an amateur artist, and it turned out quite campy, which I liked.” From Heath’s footage, Pintoff edited down 30 minutes of film. This material was screened for Brooks.

Brooks went in without a script. He recorded his initial reactions live, embodying the man he’d heard at the theater. “I mumbled whatever I felt that that old guy would have mumbled, trying to find a plot in this maze of abstractions,” he said.

At the time, recording improv dialogue for cartoons was trendy. Faith and John Hubley had pioneered the style in TV commercials and perfected it in their Oscar winners Moonbird (1959) and The Hole (1962). It appealed to Pintoff. “I’m a jazz musician and I like improvisation,” Pintoff once said. “It frees me. I dig emotionalism.”

Yet the off-the-cuff nature of improv recording always meant extra work on the back end. It took Pintoff roughly a year to edit Brooks’ dialogue and Heath’s animation into what would become The Critic. The end result is all-killer, no-filler. And it creates an illusion of effortlessness.

Which is what makes The Critic work so well. The film flawlessly disguises itself as a gag tossed off in the moment. Like Brooks’ own ability to tell a joke, it has a sense of spontaneity built atop endless hours of practice. It lands because it feels casual. And it feels casual because it was anything but.

2. Global animation news

The long tail of a failed Chinese film

Back in January, the Chinese animation anthology To the Bright Side had its wide release in mainland China. And it bombed — terrifically. After six days in theaters, it earned the equivalent of under $200,000.

This mattered because To the Bright Side wasn’t just another anthology. A lot was riding on it. The film took a bold stand against China’s commercial, IP-driven animation business.

The idea behind it went something like this. Seven indie animators with ties to Feinaki Beijing Animation Week, the festival dedicated to non-commercial animation in China, came together to turn seven picture books into films. Wang Lei, the producer of To the Bright Side, argued that “these young people do not bow down to money. They keep their own ways and do things that they love.”

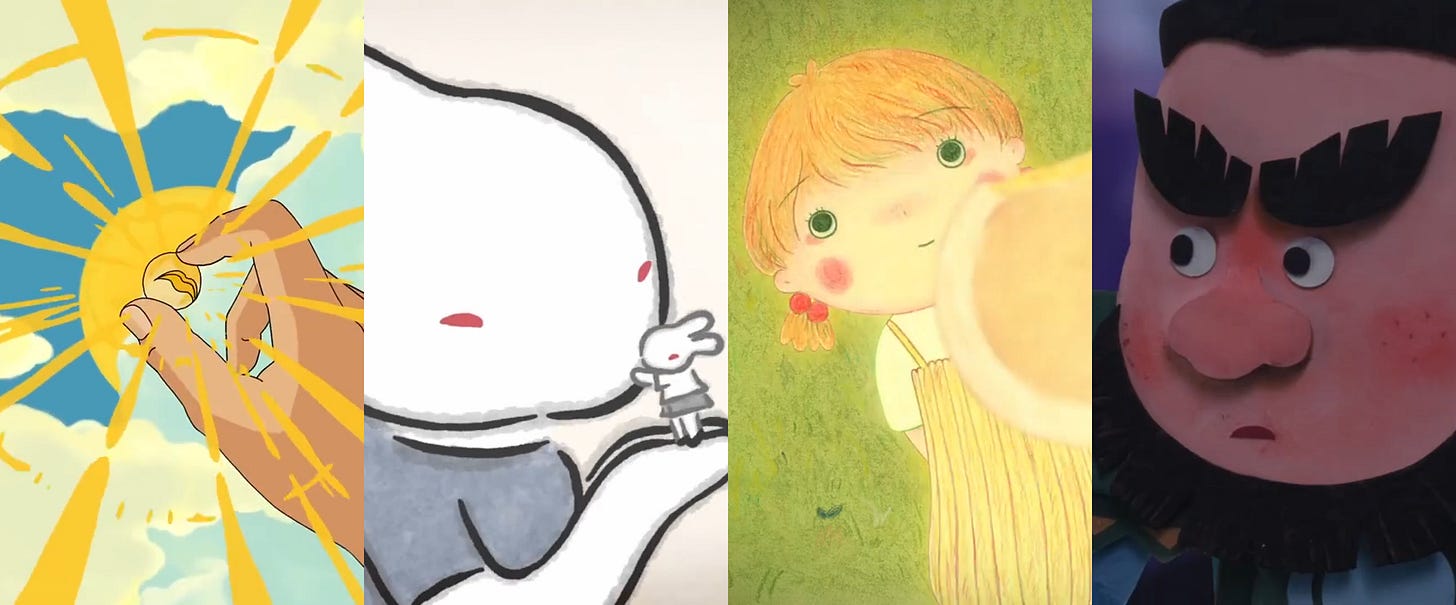

The result was a series of personal films, made in a wide range of styles. Wang compared it to Shanghai Animation Film Studio’s older output. (A veteran of that team, Chang Guangxi, was a consultant on To the Bright Side.) For the animators involved, the appearance of work like this in mainstream theaters was a landmark moment. If it did well, they thought, it could be a turning point.

It did not do well.

Normally, that would’ve been the end. Yet To the Bright Side is still getting coverage — the popular Anim-Babblers published a deep dive into the creation of one of its chapters just this week. The site urged readers to seek out the film, which premiered on the Chinese streamer Bilibili in late June.

Looking at To the Bright Side’s Bilibili page now, a few weeks in, two things stand out. First, it has over 1.2 million views. Second, the reviews are glowing — the rating stands at 9.8/10. As one comment reads, “I wasn’t able to go to the theater in time to support; seeing it now, I feel very moved. Thank you, teachers, for the warmth you’ve brought us.”

The audience may be niche, but the love is there. And the film is still getting more attention than most current indie animation does in China. The story of To the Bright Side may not be over just yet.

Best of the rest

In America, the Emmy nominations are out. AWN rounded up the ones for VFX and animation.

Also in America, Marcel the Shell with Shoes On is becoming A24’s little film that could. After cracking the top 10 at the box office last week, we learned today that its revenue rose 79% this weekend.

The Spanish studio behind Pocoyo is bringing out “its first original project in 15 years” — a new children’s cartoon about a girl and her yeti.

Nintendo is buying the Japanese animation studio Dynamo Pictures, renaming it Nintendo Pictures and setting it to work on “visual content utilizing Nintendo IP.”

There’s a new book about the history of the British studio Smallfilms (Clangers, Bagpuss), published by the BFI.

Via Wuhu Animator Space, Tongji University and Tsinghua University showed off some of the most impressive Chinese graduation films we’ve seen all year.

The Ukrainian feature Mavka: The Forest Song, whose production continues amid the war, has been prebought for the French market by Universal.

In Russia, there are plans to offer a 20% rebate to animation studios working in the Kaliningrad Oblast. (Meanwhile, there’s been an eightfold increase in so-called “torrent showings,” where theaters screen pirated movies.)

The Norwegian-Belgian project Valemon: The Polar Bear King continues to pick up speed, gathering a new round of funding in Belgium this week. It features character designs by Peter de Sève (Ice Age).

The French animation site Catsuka has a cool new feature. It’s embedded around 16,000 films and episodes that are freely available on YouTube — and made them sortable and searchable, almost like a streaming service.

Lastly, in a special (free) Thursday edition, we looked at how they designed the characters of Cowboy Bebop. It’s one of our most popular issues to date.

Thanks for checking out our issue today! We hope you’re liking it so far.

The final section below is for paying subscribers (members). We’re exploring two retro ads from 2001, created by Studio Ghibli. Their style is very far from what you might expect — and very, very fun.

Members, read on. We’ll see everyone else next time!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.