Welcome back! It’s time for a new Sunday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s the plan:

1) Human artistry vs. the machines.

2) The animation news of the world.

Before we start, one tidbit — Spanish animator Bieito Casal shared an amazing send-up of the “Ghibli food looks so delicious” videos that bounce around social media. It’s really funny (and painful), and the level of effort is mind-blowing.

With that, here we go!

1 – A logical outcome

It’s a story about right now, even though it happened over a decade ago — and not in animation.

The year was 2013. A couple of mobile game developers, Ziba Scott and Alex Schwartz, were having career trouble. They’d put time and money into a few games that were getting great reviews — but not really selling. The market wasn’t there. In fact, most of the games competing with them on Google Play were free, throwaway clones.

So, Scott and Schwartz had an idea. They’d mock the state of mobile games by making their own clones. They’d fill up Google Play with their own junk — worse junk. “Slot-machine games seemed like the perfect fit,” Scott told Game Informer in 2019, “because they have such a low barrier to entry.”

The two of them bought a pre-made slots game ($15) and used it as the basis for an automated system. Per Game Informer:

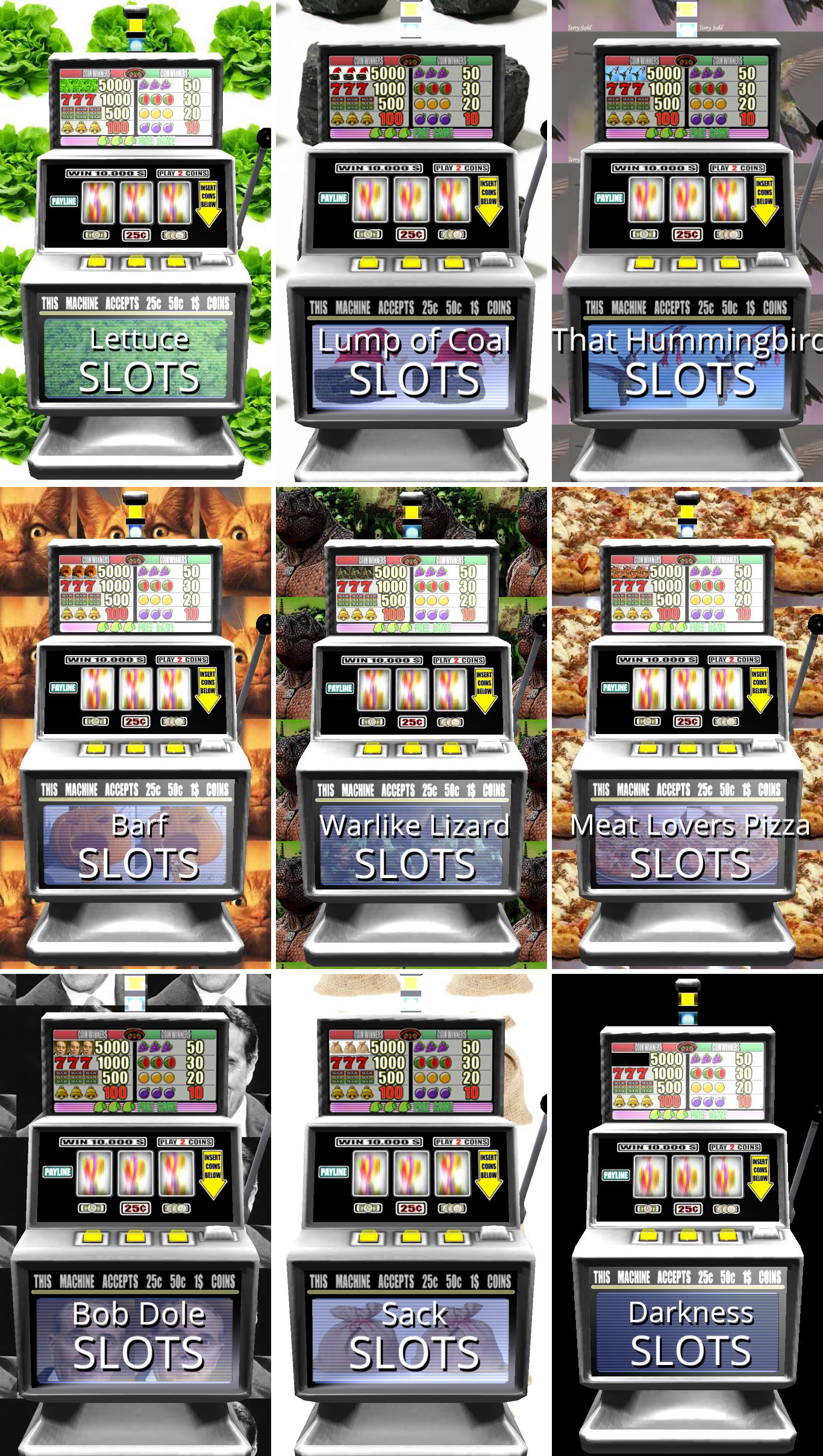

Scott wrote a Unity editor script that automatically grabbed images off the web, swiped an about blurb from Wikipedia and then used a text-to-speech program to generate new lyrics to their electronic theme song. At this point, all Schwartz and Scott had to do was type a theme into their Unity editor and the program would spit out a new slot machine. Before long, they had dozens of slot games with titles as absurd as Lobster Slots, Richard III Slots and Harlem Shake Slots.

It was a kind of practical joke. They made at least a hundred games, all bad on purpose and all functionally identical. Then Scott and Schwartz uploaded the games with ads enabled and went about their lives.

When they checked back a few months later, they were shocked. Their fakes had earned thousands of dollars. No individual game did that much — but there was strength in numbers.

That inspired Scott and Schwartz to go all in. They perfected their system, automating every step — down to filling out the Google Play forms and uploading their games. As Scott said at Game Developers Conference 2019, they “reduced the gap between conceiving of a game and having it live in the marketplace to typing in one word and pressing enter.”

The two of them would upload 1,500 slot machine games in all, and earn $50,000 in ad revenue. Their total downloads went well north of 1.5 million. The biggest hit was 3D Sexy Skin Slots - Free, with over 200,000 downloads. It’s still on Amazon now.

In the end, Scott and Schwartz abandoned their experiment in 2017. By flooding the market with automated junk, they’d proved some kind of point (and made real money). When they shared their findings with their peers at GDC 2019, an audience member asked whether AI automation might one day play into the trends they’d exploited.

“This is all just terrifying,” Scott replied. “It’s not just mobile — everything is going to be susceptible to bold new methods of creating things in volume. We’re just on a wave of that and it’s gonna happen. Let’s all enjoy that.”

Today, we’re living in the world Scott predicted. Automated junk is more powerful and plentiful than ever. Like a New York Times headline put it last month, “AI-Generated Garbage Is Polluting Our Culture.”

The pollution is seeping into everything. That article in the Times pointed it out in scientific papers, in social media posts, in search results and in once-respected magazines like Sports Illustrated. Not to mention in the stuff that kids watch on YouTube: “music videos about parrots in which the birds have eyes within eyes, beaks within beaks, morphing unfathomably while singing in an artificial voice.”

It’s claiming jobs, too. A full year ago, there were reports that game artists in China were losing work to AI in huge numbers. Soon after, Marvel put a piece of AI animation in front of its Secret Invasion series. Things have picked up speed around the world since then.

Now, you have AI animated shows and films, and a widespread and casual use of it in marketing. You see it pop up in cult movies and, a few days ago, in a Pink Floyd video. This AI output tends to be pretty bad. But what case is there for quality when quantity is faster, cheaper and just as likely to succeed?

In itself, machine learning can be a valuable tool. If you’ve ever opened Google Translate, you’ve benefited from it. This technology can be used for good. At the same time, generative AI has accelerated a trend that’s been building for years — since before ChatGPT or Midjourney.

The trend is this: automated junk is burying, even replacing, human artistry.

Back in the 2010s, Scott and Schwartz named their spam machine “The Goose” — because it laid golden eggs. Its success, like Scott said, hinged on taking up space: “most people [were] probably getting to our apps by searching for something they actually wanted and just stumbling over us instead.” Earning more money involved getting people “sidetracked by us more often.”

With AI, companies can generate unlimited junk in this vein. That New York Times article put it succinctly: “short-term economic self-interest encourages using cheap AI content to maximize clicks and views.” Even in animation, too many companies think they’ve found a goose of their own. And it might be true.

What if it is true? At a time when everything favors the robots, what does it mean to create human art?

We recently put that question to Jonni Peppers, one of America’s most fiercely independent animators. Her feature film Barber Westchester, which she animated mostly by herself, wowed us a few years ago. It’s deeply personal — the kind of movie that no one but her could’ve made. We’re eagerly following her next one: Take Off the Blindfold, Adjust Your Eyes, Look in the Mirror, See the Face of Your Mother (trailer).

This is part of what she told us:

… the invention of AI-generated instant noodle art is actually a bit of a sore spot for a lot of artists. There’s this sort of idea that AI will be used to replace all human artists until all we have left is random computer junk. I can empathize for sure, and before I say this I want to emphasize that I am not out of touch — but I am a crazy artist divorced from the animation industry who has nothing whatsoever to do with it and doesn’t care about anything that comes out of it, so take my thoughts with a grain of salt — but I wonder to what extent this even makes sense to worry about.

For me, the thing that will always matter the most in art is seeing the world from someone else’s perspective, and understanding their emotions and feelings. So, even in the event that we have to compete with computers, they will never be able to replace our perspectives and feelings, because they are ours and our art is an expression of our souls! Even if robots get souls, they can’t replace ours.

For many artists, art is a job. That’s held true under capitalism and under communism. Pursuing art full-time without making it your living (whether via paychecks or Patreon) isn’t an option for most people. And so, when automation threatens artists’ job security, that’s scary.

At the same time, Peppers raises a great point. Automation can’t ever take the place of human art — not really. The two things are different. In her words:

Your goopy essence of the inside of your emotions is your reason to create, and a robot can imitate it but will never steal your perspective, your feelings, your experiences. I really think we should use our anxiety about robots replacing us to create even weirder, messier, human-ier work that is un-imitatable and strange in a way only a human can do.

Put another way, the best battle plan against automation might be to go where it can’t go. After all, human art will always be able to do things that are off-limits to robots.

In her email, Peppers noted that she doesn’t believe in the theory that art and artist can be separated. “All of the elements that go into the creation of an image are integral to what it is,” she wrote, continuing:

If you were to separate the projector’s light from the film, you would just see darkness. Separate the artist from the art and you have nothing to understand. Separate the medium from the art and nothing got made.

Human art comes from a different source than robot art. Peppers doesn’t discriminate (“I think first and foremost I want the robots to be free”), but her take is, again, that human artists can be human-ier. In fact, she thinks that they need to be.

It brings to mind Guillermo del Toro’s fiery comments at Annecy 2023. “I think that we need things that we know are made by humans to recover the human spirit. I love things that look handmade,” he said. Midjourney didn’t worry him — his problem is with the human “stupidity,” at the executive level, that allows bad AI art to take over.

He chose blunt words: “I think when somebody calls stories ‘content,’ when somebody says ‘pipeline,’ they’re using sewage language.”

Whether or not you follow del Toro that far, he was making a point. The robotization of art happens first on a structural level. AI is just a tool that helps it along. And the way to beat the problem may be to fight for the most human elements of human art — at every stage, from idea to execution to distribution.

People still want human art (look at what The Boy and the Heron is doing in China right now), but they often can’t find it, or can’t recognize it before it’s swept away. Many factors play into that problem — it’s structural, and it’s what let Scott and Schwartz succeed in the 2010s. They could bury and replace other, better games because the whole system favored it.

Like Schwartz told Game Informer, their slots apps were:

… the logical outcome to a completely open, uncurated platform. Quality goes down, people think of various schemes to flood the market and consumers are left with a low-quality experience overall. I feel very passionately that consumers should have a curated experience. So this was us jumping over the tiniest of tiny fences to go muck around in an open ecosystem to show people how bad things are, and how bad they can be.

Algorithmic curation has the same trouble. You stumble upon automated junk all over YouTube and TikTok. Kids get served weird, creepy spam animation. The system is broken. In a great video essay about algorithms and junk videos last year, Lily Alexandre said, “While humans produce content sludge, the artist is the algorithm. And while humans consume content sludge, the audience is also the algorithm.”

In the end, the answer might be to do something else entirely.

As jobs have grown scarce in America’s animation industry, a number of artists have gone independent. They’re trying to tell their own stories — not corporate ones. Peppers herself runs a film festival that comes from her “dark, twisted desires for spaces where human art can breathe.” She wants to use curation to surface this work.

On the about page for her festival, she lays out the problem of getting human art seen today. She acknowledges that it’s almost impossible. “So it’s up to us to make a counterculture with our bare hands,” she writes. “In my opinion, the way this happens is if more people are encouraged to make art and film, both through seeing a diverse interesting selection, and knowing there are avenues for their work to be seen.”

Right now, the incentives favor automated junk. People are trying to regulate generative AI, and this is important — but artists have been boxing with Lobster Slots for years. Without a new structure, a renewedly human way of thinking about art (not content) and how it spreads in the world, automated junk will keep finding ways to win.

It’s something we discuss a lot at Animation Obsessive, internally. We read about The Goose when its story came out in 2019, and that’s informed our decisions since. This newsletter was designed, from the start, as one small attempt at an alternative.

But no single project can fix these problems — there are too many. And big companies are moving toward more automated junk, not less. Still, there can be alternatives, even if they’re tiny at first. Making painfully human art and bringing it to people in a human way, building “a counterculture with our bare hands,” can happen. It will take time. But it will be worth the effort.

2 – Newsbits

Speaking of The Boy and the Heron in China — the film is breaking records. Right now, Maoyan has it above $72 million, following its April 3 release. It’s Hayao Miyazaki’s biggest film in China, earning more there than it’s earned in Japan.

The American film Mmanwu, part of the growing indie animation push, met its Kickstarter goal of $60,000.

Check out the beautiful trailer for Bluebird in the Wind by Ellis Kayin Chan, an animator based in Spain. He writes, “Two and a half years of self-animating, painting and producing, it is to honor my sister’s passing.”

In Pakistan, the long-awaited Glassworker is set to release this summer. It’s a feature-length film inspired by Studio Ghibli, and very ambitious. The director shared its official poster on Instagram a few days ago.

We’ve learned that Shiyoon Kim, a veteran of American animation who’s worked on everything from Tangled to Zootopia to Spider-Verse, has a newsletter. He’s been sharing insights about art and process since February.

Another cool American story: new Warner Club News materials have emerged. It’s an internal publication made by the studio, and it’s full of great pictures from the mid-century Looney Tunes era.

The daughters of Manabu Ohashi, the late Japanese animator, are publishing art from his archives on Twitter. Check out this thread of designs for Princess Arete, and these sketches for The Golden Bird.

In South Africa, Triggerfish released a detailed behind-the-scenes video featuring the team from Enkai, which won an Annie this year.

Italian animator Giulia Martinelli interviewed Nikita Diakur about his surreal experiment Backflip (the film is on YouTube).

A series from Chile, Wow Lisa, has landed a spot in competition at Annecy 2024. It uses a great-looking hybrid style of 3D animation and live sets.

Lastly, we wrote about the contentious period when Disney hired an avant-garde animator to work on Fantasia.

See you again soon!

Remember CEOs and Executives are easier to replace by AI and the company gets a huge cash return to hire artists and create wonderful art

We do, indeed, need to be more "human-ier." It's the only way!!