Creating the Characters of 'Cowboy Bebop: The Movie'

Plus: global news and that 'Flintstones' commercial.

Welcome! It’s Sunday, and that means a new issue of Animation Obsessive. Our plan for today is:

1️⃣ A look at the designs for Cowboy Bebop: The Movie.

2️⃣ International animation news.

3️⃣ That Flintstones commercial.

If you haven’t signed up yet, it’s free to receive our Sunday issues each week:

There’s also a paid option, which keeps our newsletter independent and ad-free — and gets you access to members-only stories. With that said, let’s go!

1. Real people

Back in July, we wrote about how they designed the characters of Cowboy Bebop. We liked that piece — a lot of readers did, too. At the same time, it left loose ends. We found great material in our research that we couldn’t use then. Specifically, the design work for Cowboy Bebop: The Movie (2001).

This film, which is also known as Cowboy Bebop: Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door, is a fan favorite. It’s an extension of the series that reunites the main cast, but it’s very much its own thing. Like director Shinichirō Watanabe said, the film stands alone:

I wanted to make a film that people who just happened to be in a movie theater would find interesting. It’s not that I wanted to do a film that is a continuation of the TV series. […] I want you to think of the movie version as an independent work.1

For Cowboy Bebop: The Movie, Watanabe reteamed with many of his key collaborators from the show. That included writer Keiko Nobumoto, composer Yoko Kanno and character designer Toshihiro Kawamoto — who’d designed the original main cast.

“I think everyone thought that there was more we could do than we had already done,” Kawamoto said. “And the director, Mr. Watanabe, had a lot of ideas.”

Today, we’ve decided to write a little companion piece to our last Cowboy Bebop issue — tying up those loose ends, and covering the characters of Cowboy Bebop: The Movie.

Behind the scenes, there wasn’t a lot of time between the end of Cowboy Bebop and the start of the film. Kawamoto’s early sketches for Cowboy Bebop: The Movie are dated February 1999 — less than a year after the show’s TV premiere.

But the anime industry moves fast. In the short gap between Cowboy Bebop and its film adaptation, Kawamoto had already jumped to several other projects, including one with more realistic characters than Cowboy Bebop had used. “He forgot the Bebop style,” Watanabe noted. Kawamoto had to work to get it back.

Still, there was continuity between the series and the film. The former had been a collaborative, “freewheeling” project (Keiko Nobumoto’s word), and it happened again.

Three directors and a small army of storyboarders worked on Cowboy Bebop: The Movie. “The reason ‘Bebop’ is in the title [of the show and film] is that I wanted it to be a project that let each staff member ad-lib,” Watanabe said, “incorporating what came out of mutual inspiration into the work.”

Kawamoto was set loose on the characters once again. By this point, the tone and style of Cowboy Bebop were in place — he knew how to get finished designs with fewer revisions. His initial sketches for the film often look similar to the final characters. The main issue was, again, consistency.

“Because the film takes place between episodes 22 and 23 of the TV series, I couldn’t do anything drastically different,” Kawamoto said. “I had to keep things looking like the show.” In his words, his job began like this:

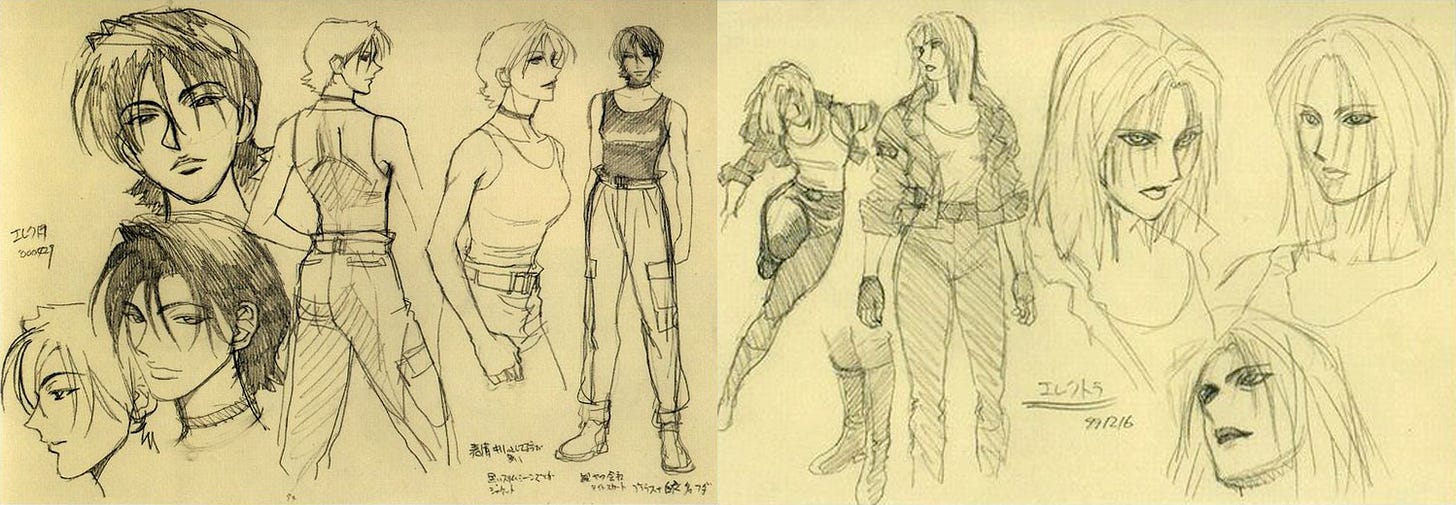

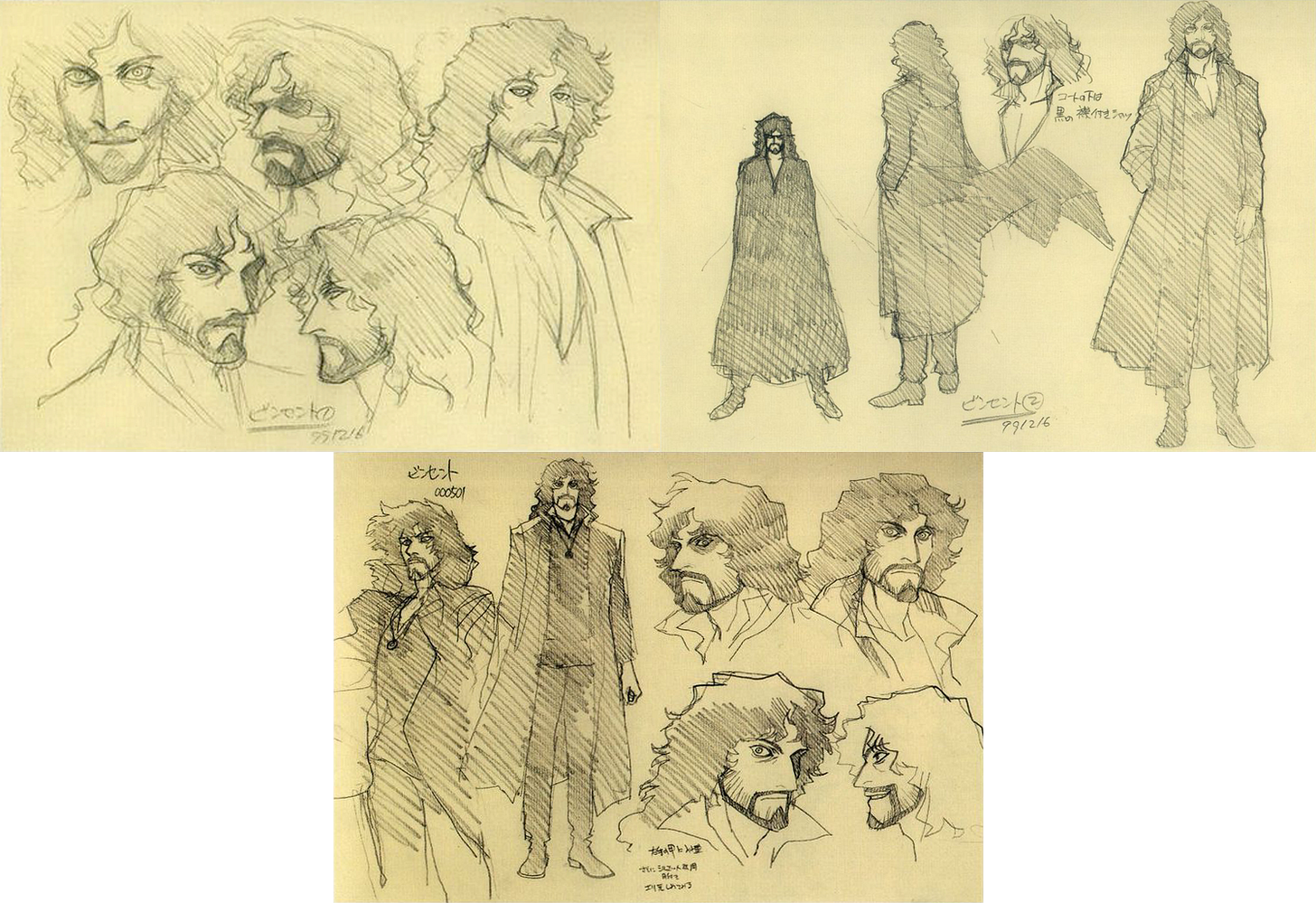

I started with the designs of Vincent and Elektra, the new characters in the movie. I had meetings with the director and simply drew them, following the same procedure as the TV series. For the movie, I was told the images of specific [actors]. The key word for Vincent was “a saint-like devil.” So, I imagined him to wear a Christ-like aura with a diabolical heart. I made some adjustments to fit him into the Bebop style.

At Watanabe’s request, Vincent was based in part on Vincent Gallo, an American actor. Still photos of Gallo were some of Watanabe’s earliest reference points for the film, during the making of the TV series. (Even before the story, he had his villain.)

Meanwhile, Elektra’s look seems to be borrowed from actor Gina Gershon, another American. The request was for a “woman of mixed race with [a] slightly dark complexion” who is “strong and cool,” Kawamoto recalled. Her character sheet explained that she would show her vulnerable side to Spike and Spike alone.

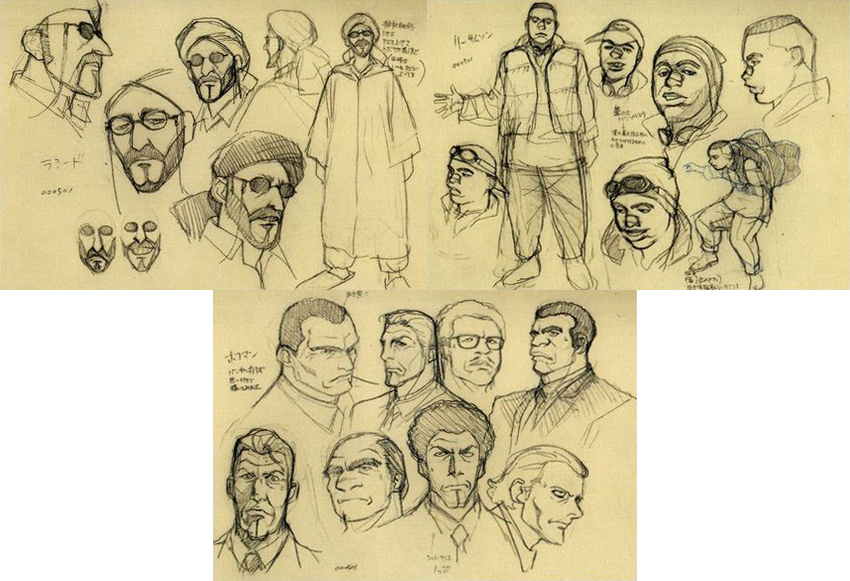

On this film, Watanabe asked for a diverse extended cast, and Kawamoto delivered. “We wanted to create a society where various religions and cultures are integrated, so therefore it was natural to portray various characters and ethnicities,” Kawamoto said.

In the planning stages, the team settled on the idea of visiting Morocco and adding aspects of the Arab world to the film. This was the origin of the guide character Rashid, who leads Spike around in a hypnotic sequence. Kawamoto again:

Rashid indeed is exactly like the guy who guided us when we were in Morocco. He was at the extreme of being stylish, wearing a black turban, yellow djellaba (hooded long coat) and yellow babouche (slippers).

It was yet another example of direct reference impacting the cast. That happened a lot on this film. When Kawamoto gave the hacker Lee Samson a “hip hop feel,” he also modeled him on an unspecified person (quite possibly Nas). Meanwhile, Watanabe said the main robber in the famous convenience store sequence came about like this:

… Keiko Nobumoto said she could not get any inspiration. So, we decided to use an existing actor as a model, and the character was based on Renji Ishibashi. When we offered him the part for real, we were half-joking, and doubted that he would actually agree to do it. But then he did!

All of this reference helped to give the cast of Cowboy Bebop: The Movie a grounded realism. That was Watanabe’s goal. He told Starlog that the hyperstylization of anime was one of his “biggest dissatisfactions” with the medium — he wanted character designs that came off “like real people.” Even in the voice acting, he searched for a “raw, naturalist feel.”

And, maybe because he was still a bit rusty, Kawamoto delivered even more realism than usual. The characters in Cowboy Bebop: The Movie, like the film itself, almost get close to the hyperrealism of anime like Jin-Roh from that same era. It’s maybe not a coincidence that Jin-Roh’s director oversaw a sequence of this film.

“It’s not just the images; we pushed ourselves on the story, on facial expressions, on everything — I wanted a real feature-film format,” Watanabe said. Kawamoto played his part in making Cowboy Bebop: The Movie not just a return to the show, but something different and daring. The team that gave us the freshness of the first series couldn’t settle for less than giving us freshness again.

2. Animation news worldwide

Ralph Eggleston, 1965–2022

On August 28, one of the architects of the Pixar look, Ralph Eggleston, passed away at the age of 56. Variety reports that it followed “a long battle with pancreatic cancer.”

Inaccuracies on IMDb have led to some confusion over Eggleston’s career trajectory, but the lengthy obit by Cartoon Brew tells his story as it should be told. “Eggleston joined Pixar in 1993,” it notes, “at a time when few people had heard of the company.”

He quickly became a linchpin of the studio’s creative process — starting a career there that ran from Toy Story up through Soul. Per the article:

When the end credits of Toy Story begin, Eggleston’s name is first listed. He is credited as art director, but he was also the film’s production designer, a credit that the studio hadn’t yet started using. Having never worked in CG before, Eggleston became responsible for the cohesive visual appearance of the 400 CG characters, props and sets made for that film, providing detailed drawings and written notes to the fifteen or so modelers and technical directors.

Alongside his widely respected work as an artist, his influential use of “color scripts” and his Oscar win for For the Birds (2000), Eggleston was a cherished member of the animation community. The news brought an outpouring of tributes from the industry.

“My heart is broken,” tweeted Dice Tsutsumi (The Dam Keeper). “Ralph is the one who pushed for me to join Pixar. Brilliant production designer and dedicated filmmaker. I learned so much about making film from him.”

Eggleston was a “true titan of our art form,” wrote Jorge R. Gutierrez (Maya and the Three). “Before many knew he was sick, he was trying to donate his spectacular art book collection to a Mexican animation school. That’s Ralph.”

In the words of Angus MacLane (Lightyear), Eggleston’s “massive talent was matched only by his kindness.”

Best of the rest

Japan’s legendary Sherlock Hound is coming to Blu-ray in English (and Japanese) via Discotek Media. It’s now available for pre-order.

In Croatia, Zagreb Film has started to upload its classic animated shorts in restored quality on YouTube, for free. (Thanks to Toadette for the tip!)

Animation Magazine has an extensive feature on the gorgeous Perlimps, from Brazilian director Alê Abreu (Boy and the World). Among many other things, we learn that “it took about nine years to complete the movie.”

Pinocchio by Guillermo del Toro and My Father’s Dragon by Cartoon Saloon will have their world premieres in Britain this October.

New Gods: Yang Jian topped China’s box office for the second week in a row, taking in $43.4 million after 10 days. (Wuhu Animator Space has an interview with director Zhao Ji that includes plenty of concept art.)

Meanwhile, One Piece Film: Red became Japan’s tenth-biggest animated film ever, dethroning Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 and continuing the franchise-film boom.

On that note, American streamer Crunchyroll will have the hit feature Jujutsu Kaisen 0 starting September 21.

French producer Hanna Mouchez says that streamers’ demand for exclusivity plays havoc with financing. European animation relies on money from groups of broadcasters and backers. Exclusivity makes it harder for studios to fund their work even as it helps streamers grow.

In Russia, Soyuzmultfilm trumpets its transformation into a licensing giant, with “over 250 licensing contracts in 50 product categories” over the last five years. It continues to convert Soviet-era art films into brands and merchandise.

Lastly, the Ukrainian animation festival Linoleum will stream for free via Megogo from September 7–11. (There will reportedly be some region locking.)

Thanks for reading so far!

We hope you’ve enjoyed our last few unlocked issues, celebrating our one-year anniversary of paid subscriptions. Starting today, our usual format is back. The final section of this issue is for members.

Below, we study that Flintstones cigarette ad from the ‘60s — the weird one. We’re trying to figure out its context, and why its true notoriety came decades after it first aired.

Members, read on. We’ll see everyone else next time!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.