Happy Sunday! Thanks for joining us. It’s a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and the plan goes like this:

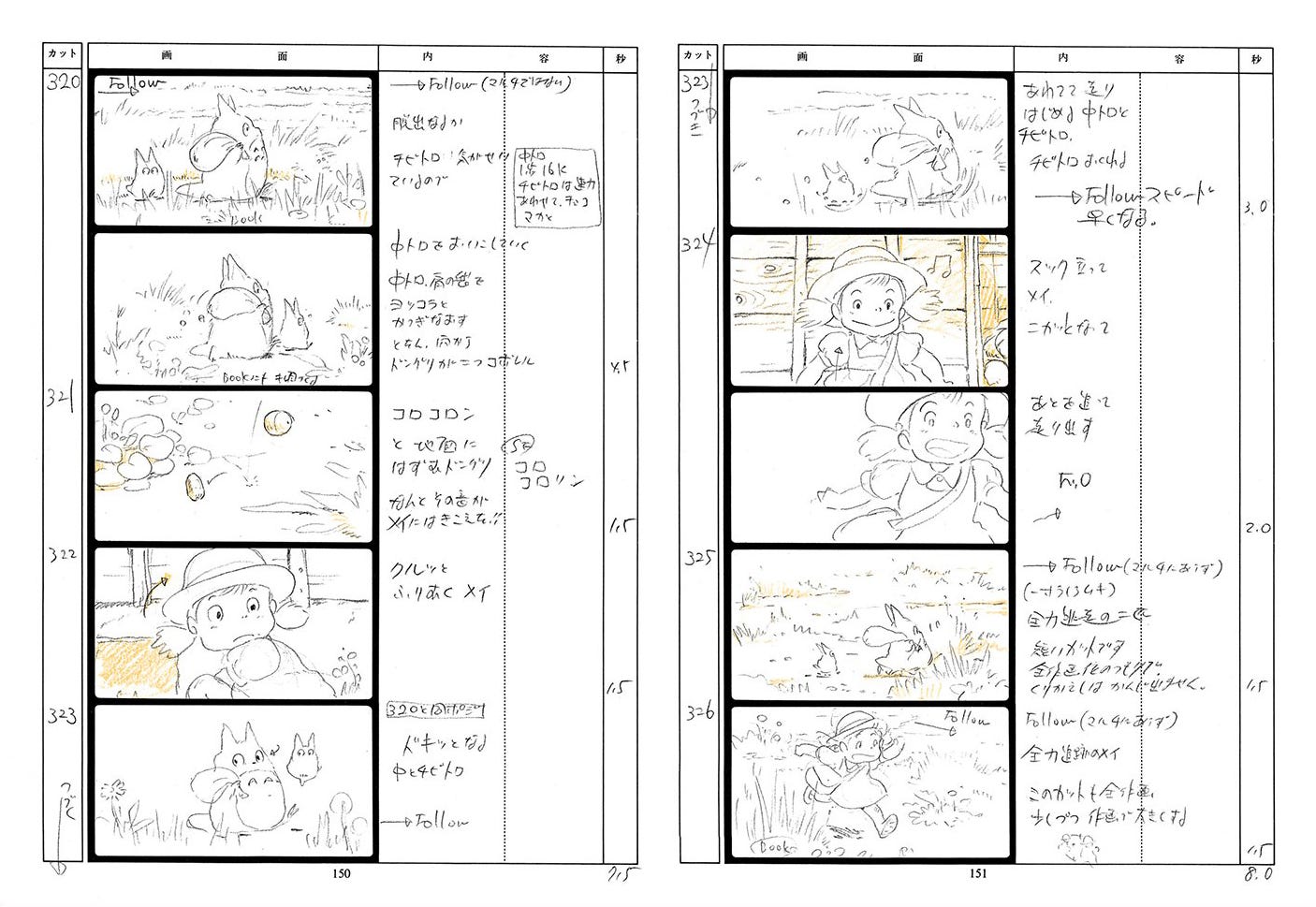

1) Kazuo Oga’s work on the backgrounds of My Neighbor Totoro.

2) Animation newsbits.

With that, we’re off!

1 – “Is this your standard, Oga-san?”

Background paintings matter at Studio Ghibli. Its films are about more than animated characters: they present environments, living worlds. The painters who crafted the trees, rivers and cobblestones in movies like Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989) played as essential of a role as the animators in making those stories feel real.

Among the Ghibli painters, a few stand a little above. One was the late Nizo Yamamoto, background supervisor on Grave of the Fireflies and more. Another, even more famous name is Kazuo Oga, who took the lead on My Neighbor Totoro (1988).

Totoro was Oga’s start with Ghibli. He’d come from elsewhere in the industry, working in TV, at the background studio Kobayashi Production and on big movies like Madhouse’s Harmagedon (1983). But Totoro changed him. A strong artist became a master painter. And Oga has kept showing that mastery since, most recently with The Boy and the Heron.

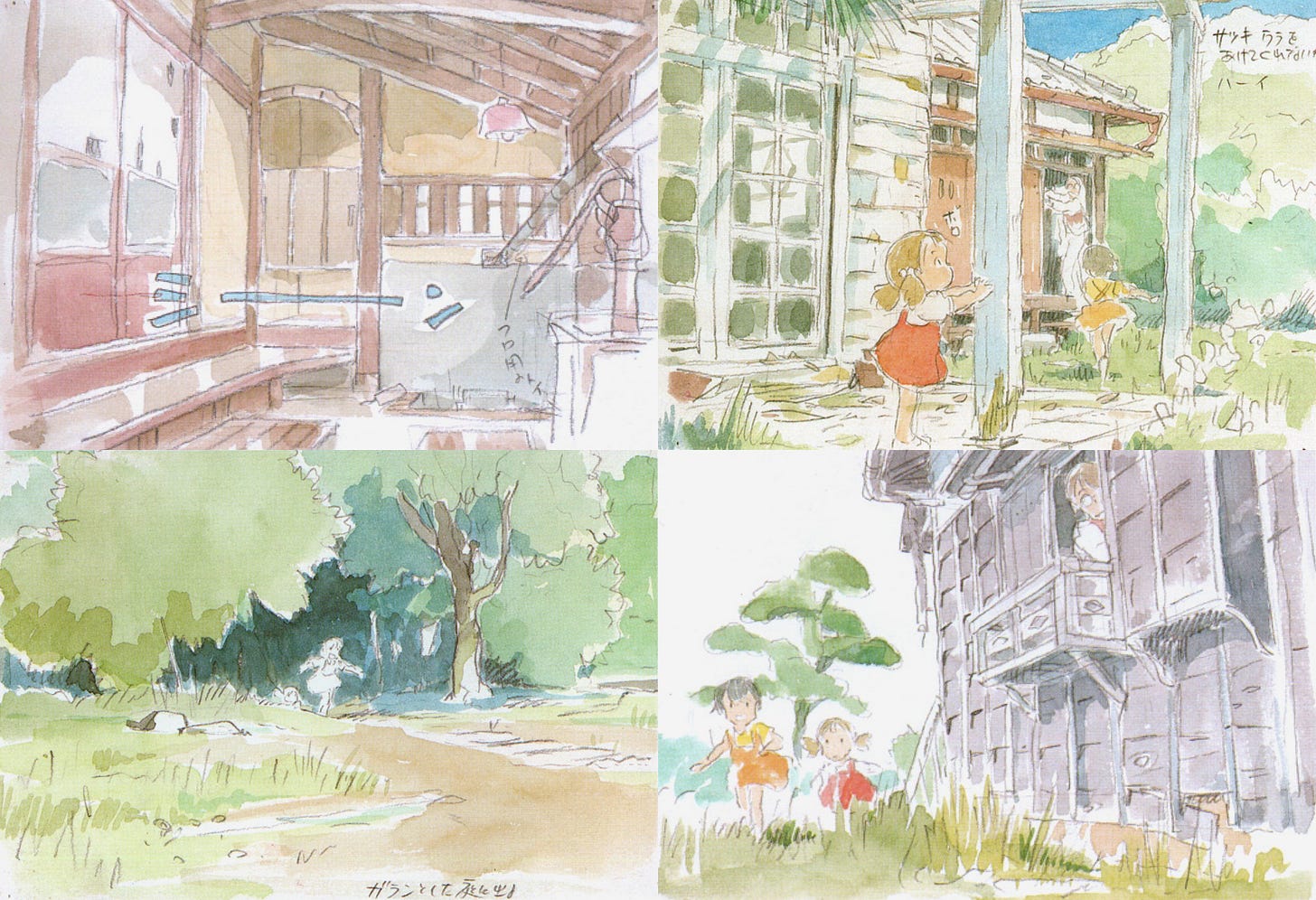

For Totoro, Oga created most of the “art boards,” the concept pieces that charted a course for the other background painters’ work. He also oversaw and corrected their art, and painted many backgrounds himself. Without him, the film wouldn’t have looked the same.

During a Japanese interview in the mid-1990s, Oga spoke about his Totoro experience, and about what Hayao Miyazaki asked of him. It’s a fraction of a huge, career-spanning talk published in the 1996 book Kazuo Oga Art Collection (available on Amazon Japan). We definitely recommend it as an import — even decades later, the images are still worth it by themselves.

Which brings us to our topic. Translator and animation researcher Toadette — who’s helped us a lot over the years — was kind enough to provide us with an English version of Oga’s discussion of Totoro. It appears below, with our copyedits.

Invited by Miyazaki-san to My Neighbor Totoro

— With that, next is Totoro. How did you get involved with this project?

Oga: In the beginning, Miyazaki-san contacted me directly. However, my thought at the time was, “I really can’t accept.” I’d just gotten my next project and I was planning to work at Madhouse for a while. But I’d been thinking even before this, “I’d like to try doing a drama set in nature.” That feeling was growing really strong for me back then. Especially since my last job was Wicked City, I wanted to try one where I could paint natural things this time. The timing was just right, you know?

So, Miyazaki-san said he’d show me the image boards. Despite thinking I probably couldn’t do it, I asked him over the phone, “Would it be okay if I just took a look?” We decided to meet that same day at a coffee shop in front of Asagaya Station.

As he showed them to me and I listened to what he had to say, I changed my mind immediately and decided I wanted to do it. But I couldn’t take it on right away without consulting with [producer Masao] Maruyama-san of Madhouse. I asked him to wait a week, for the time being… I didn’t really need him to wait that long, but that’s how I decided to reply.

Still, Maruyama-san kindly told me, “If there’s something you want to do, you should do it.” I’d always felt Madhouse and Maruyama-san had nurtured me after I left Kobayashi Pro, so I was sorry that I couldn’t do the work planned for me. But I chose to do what I wanted to do, and I decided to let myself do it.

— What was it like when you actually joined the production?

Oga: To begin with, I was delighted that the subject matter I was painting was the suburbs of the 1950s. It was also my first time working with a director who made demands about the [background] art, such as, “I want you to paint things like rural landscapes, trees and flowers, while paying close attention to them.” I did that myself and, from around the halfway point, I began to consider flowers and trees as the equals of Totoro [the character]. I painted them with that in mind.

— The film was in production simultaneously with Grave of the Fireflies at the time. Were you curious about that?

Oga: I was. Or rather, I felt anxiety as well, probably because it was my first time [at Ghibli]. Like, “I wonder if my work is that good?” So I went to look at Nizo [Yamamoto]-san’s art sometimes. Then I’d come back thinking, “Ah, mine’s still no good.” As I sat down and painted again, though, I’d change my mind and go, “This is good enough for me after all.”

— I suppose each studio has its own atmosphere. Was it difficult being somewhere new for the first time?

Oga: I wasn’t sure about the standards for my work. How much should I do? Really, it’s fine not knowing how much to do, and you should simply work to the best of your ability. But you need a little relief somewhere, right? The only source of relief here was that Grave of the Fireflies was apparently behind schedule.

Even so, things were still peaceful when Totoro started. Admittedly, it was a little noisy at times. Miyazaki-san enjoyed working on Totoro despite all that. He still does this today, but he’d walk around commenting even about plants while drawing the storyboards, like, “This is how they looked at that time.” Or he’d bring books about plants, or picture books, and show them to the animators and background artists.

In addition, we talked a lot about things that weren’t directly related to the film. Ghibli was in the middle of Kichijoji in those days. Just outside the window facing the art room was a lumber shop. There was a single camphor tree there… a fairly old camphor tree that had already started to crumble. It was hanging right before my desk. It looked as if that spot alone, in the middle of Kichijoji, had been completely forgotten and had retained its oldness. That topic came up often while we were looking out the window.

In that sense, the work may have been difficult, but we enjoyed it in its own way. Even now, Miyazaki-san and [Makiko] Futaki-san still say, “Things were nice when we were doing Totoro, huh?” That’s a favorite phrase recently.

— Just the other day, Miyazaki-san came up to me as I was spreading out the [background] art from Totoro and said, “That time was the best.”

Oga: Now that Ghibli has gotten big, we have to think about a lot of different things. In those days, it was good enough just to think about the Totoro project.

— Social attention around [the studio] has increased, too.

Oga: And you have to think about the future, right? Back then, it was a situation where we disbanded once we were done [with a film]. It’s a question of which is better. A sense of security that we can work continuously in the same place into the distant future? Or a sense that we’ll disband once this job is over and, not knowing what the future holds, devote all our energy to this one project for now…? From a manager’s standpoint, it’s probably better to think about the future, but for those doing the work, it’s easier when it’s a one-off. Well, not that it’s easier, but that you can devote yourself to it. In that respect, there was a carefreeness back then, so I suppose those days were better.

— Also, while there may have been works that depicted nature before, most of them were set in Europe. Given that, wasn’t there also a sense of excitement because the setting was Japan?

Oga: That may have been the case.

“Miyazaki-san’s comment changed my attitude toward the work”

— Were there any parts of My Neighbor Totoro where the methodology you’d used until then no longer fit?

Oga: I’d done some theatrical projects at Madhouse, but I’d spent a long period focusing on TV series, so sure enough my work was rough. I also didn’t do that much research and might have been a bit naive. Moreover, I didn’t really know what Miyazaki-san’s demands were regarding the [background] art. So, partly because I wasn’t told very much, I started painting [art] boards beside Miyazaki-san with my usual attitude in the beginning. Nevertheless, when we started the actual production and I gathered everyone’s backgrounds thinking they would be good enough, Miyazaki-san looked at them with a stern face and said, “Is this your standard, Oga-san?”

The moment I heard that comment, I was shocked, and my complexion suddenly changed in surprise. Since this was no good, from that point I started to paint for the first time with the feeling, “I need to be fully determined in order to do this.” Whether it was the light or the subdued colors, more and more I came to understand that I wouldn’t be able to achieve the pictures that Miyazaki-san was looking for if I didn’t do things more carefully.

Until then, I’d painted trees rather symbolically, and even with interiors there were parts I viewed as acceptable when they were roughly dark or bright. But I began to realize that I needed to carefully incorporate the many other trees and plants that we don’t normally pay attention to, and, even indoors, the colors of the walls and pillars and such… the color of a pillar also changes according to how the light hits it. I came to feel things like that.

— Up to this point in animation backgrounds, when it came to grasslands, it just felt like a lot of grass was growing vaguely somehow. In this work, even what’s growing there is represented. Was there a transformation in your thinking in that regard?

Oga: I think the case was, although I’d felt until then that doing this much was good enough, I needed to think about things more carefully. Instead of a transformation, it was more that [my approach until then] was lacking.

— Were there specific requests, like, “I want that area to be more like this”?

Oga: At first, I was told to use subdued but beautiful (kirei) colors. In other words, mix various colors, but make them beautiful. Also, even within a single [art] board, he would sometimes say things like, “This part is beautiful, huh?” or, “Around here is nice.” Not about the whole, but about parts. As I put together the parts he’d said were good, I began to think that maybe I could somehow get by this way, that I was getting closer to Miyazaki-san’s desired pictures.

But Totoro was an easy job, thinking about it now. The subject matter was a space similar to my own upbringing, and the era was also roughly the same, so it wasn’t like I had to worry that much in terms of material.

With this project, I guess what I thought about most deeply were the colors and how much I should show. I’d painted weeds vaguely until then, but now I would paint them accurately with an awareness of what they were, instead of painting them as just weeds. Even with trees, I would do things like sawtooth oaks, konara oaks and camphors. Totoro was the first project where I paid attention to specific things like those.

But I guess I must have known about them already. It was just that I remembered them when I tried to think about them properly. I prepared myself, thought about [my work] thoroughly, and then when I actually looked at the material, I realized I was someone who’d always seen these. I just hadn’t thought about them properly until then. When I did, the things I’d experienced in the past started to overlap and come back to me.

— When that happened, work quickly became more enjoyable, didn’t it?

Oga: It was enjoyable. I think it was around the time we were doing Only Yesterday, Miyazaki-san sentimentally said that Totoro was the good days. After all, it’s nice to be able to enjoy your work. Also, Totoro started out as a really fun little piece of about 60 minutes. It ended up getting around 20 minutes longer than expected, but I think that was part of the carefreeness as well. Of course, the work was difficult.

— When you joined Totoro, was the background staff different from the people you’d worked with before?

Oga: I was expecting there to be staffers when I went to Ghibli. But it seems [Toru] Hara-san and Nizo-san thought I would gather staff. The Ghibli staffers had all gone to work on Grave of the Fireflies. Only [Kiyomi] Ota-san said that she wanted to do Totoro, so people had to be brought in.

Fortunately, [Toshiro] Nozaki-san said he would do it, and [Satoshi] Matsuoka-kun, who was a colleague at Kobayashi Pro, helped out. The rest were [Masaki] Yoshizaki-san, who had done Castle in the Sky; [Kiyoko] Sugawara-san, who’d also left Kobayashi Pro and worked at another company for about a year; and [Yoji] Takeshige-kun, who was introduced to us by [Hiromasa] Ogura-kun. I started with those six people.

— So, rather than it being your first time, it was like you already knew each other well.

Oga: That’s right. And, as expected, Matsuoka-kun was a great help in assisting me. When I couldn’t do something myself, I could ask him, “There’s no board here, but please do it.”

Just like me, though, Kobayashi Pro people like Matsuoka-kun and Sugawara-san had rough ways of painting. How could they get closer [to the style]? I’d just begun to feel I was finally getting closer to Miyazaki-san’s work myself. So, I had to teach those two how to paint that way as well. It took quite a while for them to get used to it. Matsuoka-kun said things like, “Why do I have to paint that much?” and, “Isn’t this enough?” But they were able to empathize [with the project] and do it, in the end. I guess the Totoro material was good after all. Ultimately, Matsuoka-kun played a big role on Totoro.

“A world in which you can find comfort even on your own”

— Many say about Totoro even now, “This kind of world is nice, isn’t it?” Did the people making it feel the same during its creation?

Oga: I think Miyazaki-san was good at getting us going. Although it was a heartwarming film, the job itself was difficult. However, Miyazaki-san was so bright and cheerful that it didn’t really feel that bad for us.

— After all, it’s important to empathize with the project, right?

Oga: When working on art [direction], I never delved that much into the storylines. I just thought immediately and single-mindedly about whether a film’s scenery was appealing.

But, considering it now, I also think, “If only I’d been a little more interested in that kind of thing before working with Miyazaki-san.” Well, I always end up regretting it.

— Even Takahata-san was saying, “When I saw the preview screening for Totoro, I was really impressed.”

Oga: At the wrap party, he took the trouble to chase me down and tell me, “Oh, it was good.” I was so happy. I was thinking, “For him to say that much to me, it’s flattering…”

— It’s not just nostalgic; the scenes actually bring a lot of memories to mind.

Oga: I don’t want to use the word “comfortable” too much, but when I painted the backgrounds, I always painted with a sense that I’d probably feel good if I were in a place like this, even on my own. From that point of view, the world of Totoro is a very pleasant one no matter where you go.

So, despite having to work on Sundays and such, I didn’t hate the job or anything by the end. Certainly, the work was difficult. But still, Miyazaki and I were saying things like, “It’s coming down again,” as we looked out the window. That year, there was a lot of snow again.

The most painful thing was the schedule. I got worried, “Will it really be finished?” But, one by one, people came from other places to help us. When I heard updates like that from the production staff, I thought, “Ah, thank goodness.” Ultimately, although it was said that we wouldn’t be done before New Year’s Day, we were able to finish it about a week or 10 days earlier than the final deadline thanks to everyone’s hard work.

— This may be a strange way to put it, but the Totoro project is a happy work that was truly blessed to be born and that’s grown beyond expectations.

Oga: Even with the backgrounds, Miyazaki-san often talked about things like “happy” colors. At first I wondered, “What are happy colors?” But… I started to think about warm colors. Not piercing, raw primary colors, but softer in some way, colors that make you feel relieved when you see them. I think I finally began to understand what a happy background is by the end of the film.

— When you watched the full rush print at the end, did you have any strong feelings in particular?

Oga: I’d seen it many times by then. Certainly, adding music and sound effects will create a fairly different impression, but I was mostly just concerned about whether there’d be any embarrassing parts to watch or whether any retakes would be needed on my end. Once it was in theaters, I had absolutely no responsibility for it anymore. I saw it in a theater after work was finished and everyone had disbanded, and I was finally able to enjoy watching it.

2 – Newsbits

A fun, short video explores the making of a moment from Ireland’s Wolfwalkers (2020). It asks the question, “How to animate 163 characters for one scene?”

On the topic of Studio Ghibli, the Japanese documentary Hayao Miyazaki and the Heron has popped up on Max for viewers in America.

Arbelos Films is getting ready to bring the animation of Slovakia’s Viktor Kubal to American theaters. This is exciting news — the distributor did a great job with its Son of the White Mare release a few years ago.

A new stop-motion film from Argentina and France, Steps to Fly, has an intriguing style. See the trailer here.

Per Southern Metropolis Daily, the best-reviewed animated film of 2024 in China is Robot Dreams. It has a score of 9.0 on Douban. (The year’s top-scoring Chinese animated feature is Into the Mortal World, at 7.9 right now.)

In Cuba, there’s a fantastic interview with Silvia Padrón about archiving and preserving the legacy of her father, animator Juan Padrón (Elpidio Valdés). It includes photos of cels, storyboards and more.

Russia’s state-enforced slowdown of YouTube continues, as does the site’s drop in Russian users. While the government threatens ISPs that try to increase the site’s speed, YouTube is reportedly blocking services that Russian creators use for the “mass migration” of their videos to other platforms.

In Canada, Quebec’s animation industry is in freefall, reports Cartoon Brew. The causes: Hollywood’s recent troubles and changes to the tax credits available to animated productions.

The Chinese outlet Anim-Babblers spoke with Chenghua Yang about her film Self Scratch (2020). It came online this year — check it out on Vimeo.

Lastly, we wrote about the wonderful Ursa Minor Blue (1993) and the beginnings of digital animation.

Until next time!

Thank you for taking the time to write on Totoro and Ghibli!! I love Miyazaki’s art style and direction and it’s always nice to see content like this on Substack!

I have the art book of My Neighbor Totoro, with all the background paintings and character sketches. It might be my favorite Ghibli film re: art.