Happy Sunday! It’s a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s what we’re doing today:

1️⃣ How background painter Nizo Yamamoto rose.

2️⃣ Animating for a documentary, plus animation newsbits.

Just finding us? You can sign up to receive our Sunday issues for free, weekly, in your inbox:

Now, here we go!

1 – Happy accidents

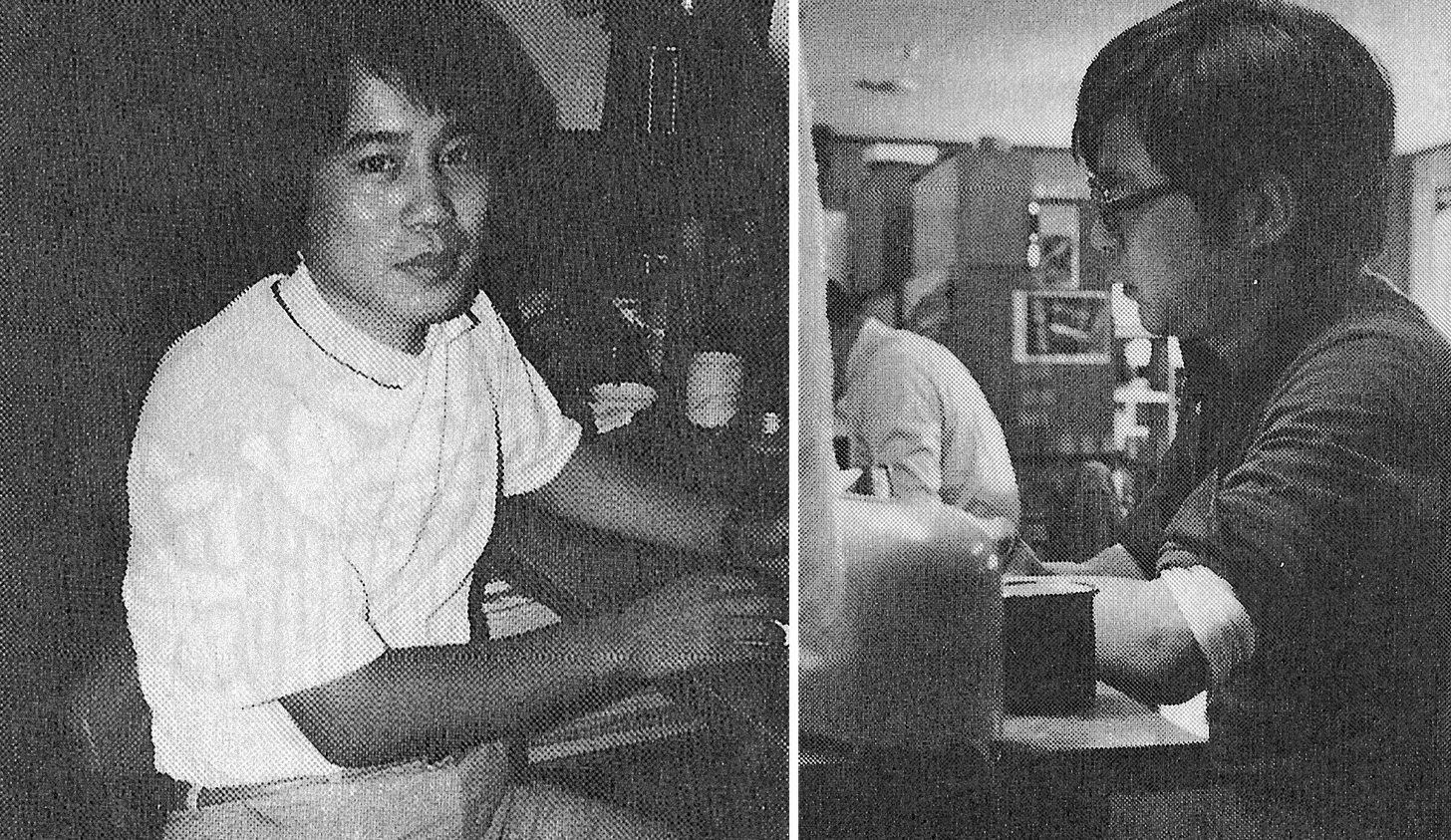

It was a shock when the news broke, last summer, that Nizo Yamamoto had passed away. At just 70, he felt too young. So many lived longer in his group, the Ghibli people — the artists who spent decades with Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata.

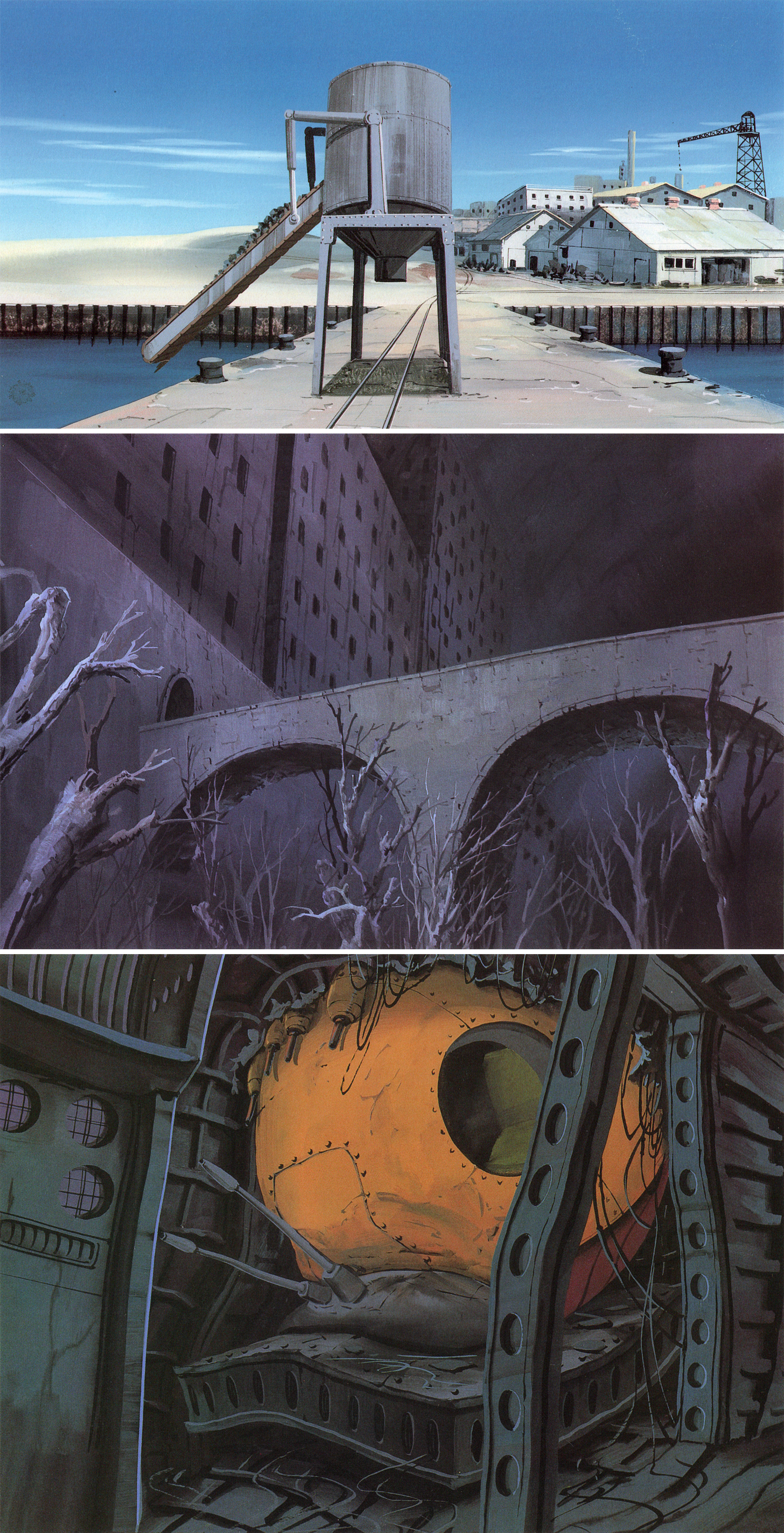

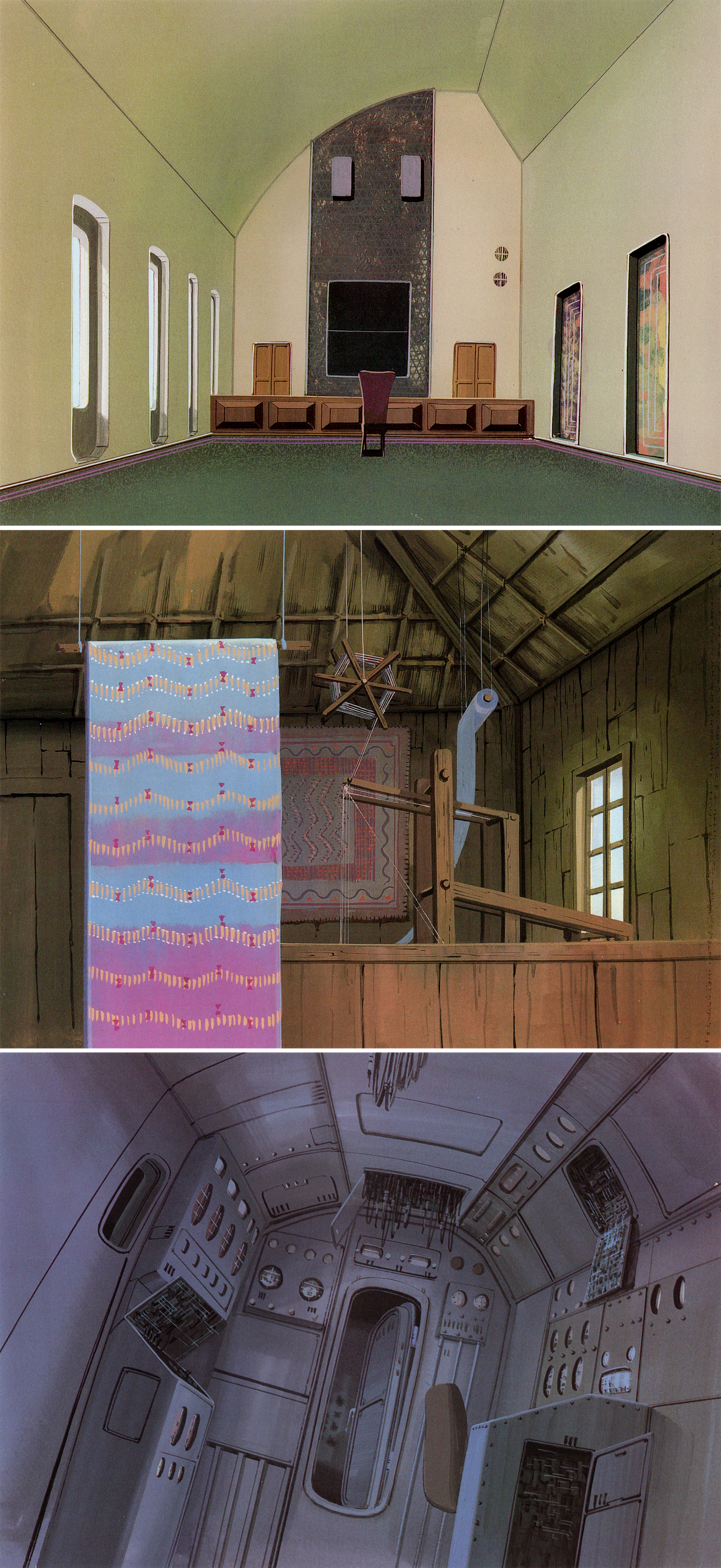

Yamamoto was an art director, which has a specific meaning in Japanese animation. Traditionally, the art director (bijutsu kantoku) supervises the background team, helps to define the places in which the story happens and ensures that the backdrops and the characters don’t clash.

Writing about Yamamoto’s job in 1993, Takahata argued that it “goes far beyond providing ‘backgrounds’ (haikei) to this or that moving manga; it is about creating a world with a sense of reality, which the viewer can enter.”1 That’s what Yamamoto did for Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies (1988), and for Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke — where he worked with four other art directors.

His name isn’t as well known as Kazuo Oga’s (also Mononoke, plus Totoro), but you know Yamamoto’s images. Among other things, the clouds in Castle in the Sky are his. They’ve been called “Nizo clouds” in the industry at times.2

He played a key part, too, in both Takahata’s and Miyazaki’s early careers. Yamamoto was there before Ghibli. In fact, he art directed Miyazaki’s debut as a director: Future Boy Conan (1978). They ended up working together almost by chance — but that project changed both of their lives.

“Yama-chan, I truly thank you for coming to us at that time,” Miyazaki later wrote, using Yamamoto’s nickname. “I’m really glad that we met.”3

Superfandom wasn’t the main path into anime when Yamamoto joined the industry. He grew up in rural Japan, somewhere on the Goto Islands, in the town of Nonokirecho. Animation wasn’t really available. Even by the ‘60s, his family didn’t own a TV.4

But he saw Toei Doga’s Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon at his middle school — the gym held animation screenings, sometimes. It seemed like an interesting career. Then events got in Yamamoto’s way: he had to take a job after middle school, while attending a vocational high school to study architecture part-time.

In the early ‘70s, Yamamoto (now 19) moved to Tokyo and took courses in art and animation. A big goal was to go into oil painting. But he got another job, this time in the trenches of TV anime backgrounds, and it ate up his study time for oils.5 Events were in his way again.

These were his circumstances when Takahata’s first hit show appeared on TV in 1974. As Yamamoto recalled:

… Heidi started around then. This was a shock for me. In those days, I usually worked from about 10 in the morning until about 10 at night, and Heidi aired right around the time we ate. So everyone [at the studio] watched it together and said, “It would be great if we could do something like this.” But I knew that, with my ability at the time, I wouldn’t be able to join such creative people. So I decided to take another look at myself.

Yamamoto took steps to improve — more education, different work. After landing a job in merch at Heidi’s studio Nippon Animation, he got to see some of Miyazaki’s endless drawings for the Takahata shows. He was blown away.

At Nippon, Yamamoto caught a break: his first art directing job, on a TV series about volleyball called Attack on Tomorrow (1977). He supervised the outsource artists in Korea for six months, side-by-side with another art director. It was a quirky project — some on his team were ex-soldiers, and he was a novice in this role. But it wasn’t a disaster.

When he returned to Nippon Animation, Yamamoto caught a second break. He got to be the assistant to art director Kazue Ito (The Dog of Flanders), who turned into his “mentor” and a key early influence.6 In fact, Ito was the one who got him on Conan.

That series, another Nippon project, was in trouble. Miyazaki was finally setting out on his own after spending his whole career with Takahata at the helm — and directing TV wasn’t easy. There was panic, despair and chaos in the Conan group. As Miyazaki later wrote:

At that time, the TV anime world was in a state of great turmoil, with the number of works increasing but a shortage of staff, and the Conan unit itself had true difficulties.

After all, it had no art designer. Well, there was one, but he was going in such a different direction [from the project] that I had him quit without another thought.

But the production continued. It was the height of insanity, but that was why we didn’t have a single background board (a picture to set the direction and serve as an example), and why the background staff (who were scattered all over the place) made pictures based only on verbal descriptions.

Of course, the backgrounds were finished. It goes without saying that I didn’t just dislike them, but was ashamed of them. This was not the fault of the staff, but of the person who tried to make them work without [background] boards. As a greenhorn director, I was brought to a standstill in front of a mountain of completed background paintings.

I’m an animator, so I don’t even know how to use poster color paints. I nevertheless decided to correct [the backgrounds]. Naturally, I quickly got stuck.

I appealed to Kazue Ito, one of the studio’s art directors, about this plight, and I borrowed Nizo Yamamoto-san, who had recently joined as an assistant. “I’ll only need him for two or three days,” I thought. … Yama-chan arrived. How happy I was. After that, the two of us worked like crazy on the mountain of backgrounds, washing, repainting and adding brushstrokes.7

Yamamoto didn’t intend to stay on Conan long. He saw it as a quick background-checking job — reviewing and correcting art, which he’d done a lot on Attack on Tomorrow. But the atmosphere of the Conan group was different. Something was happening here. His time in this “temporary” role kept extending.

And Miyazaki wanted him there, badly. Which meant something — he’s a director with a reputation for being relentless when he wants someone on his project. As he admitted, he pulled out all the stops to persuade, pressure and “trick” Yamamoto into joining. The young artist ultimately left Ito in the lurch to work on Miyazaki’s show as its sole art director. (“I feel bad for Ito-san,” Yamamoto later said.)

It was a big break, and a bigger responsibility. Conan was wildly ambitious: a sweeping sci-fi project that grounded its fantastical world in believable detail. And it had a crew for the ages, including animator Yasuo Otsuka of Lupin the Third fame.

By contrast, Yamamoto was young, with little experience art directing. He found himself in the strange position of dictating the style of the backgrounds to artists older, more respected and more accomplished than himself. His art boards, the concept paintings he used to set the style, had to be good. Like he put it:

… if I sent out sloppy boards, the background painting staff would’ve all been my superiors. So I thought that if I made the boards properly, they would understand, so I created about 300 boards. Approximately 10 sheets per episode.

There was no room for shortcuts. Conan’s story frequently darts to new locations — and each new location demanded detail. It was up to Yamamoto to translate Miyazaki’s rough sketches into actual places.

On top of the art boards, Yamamoto kept correcting backgrounds and painting many of them by himself. He compared Conan to “running a marathon.” Although he was getting orders from Miyazaki (down to the light at different times of day), and leaning heavily on the experience of color designer Michiyo Yasuda, he was operating at a new level than before.

It contrasted with his years as a background painter in the trenches. He said in 1979:

In the case of art [direction], it’s surprisingly interesting to try it. From my experience, the ego of background painting, the feeling of “trying to paint a standalone picture without thinking about its harmony with the cel,” disappears. I have to think about the harmony with the cel to a certain extent, and I have to think about the stage direction as well, which is a plus in many ways. There was a lot to learn, though.

To be clear, Conan was a meat grinder, like Heidi had been earlier in the ‘70s. The restrictions of Japan’s TV deadlines and budgets pushed up against the ambitions of the team: the only way to make something good was to overwork. And, according to Yamamoto, no one overworked like Miyazaki — he “probably got less than four hours of sleep a night.” His hair went grayer during production.

Yamamoto was pushed to the limit himself. “If Miyazaki-san puts all of his strength into it, everyone else will have no choice but to do the same,” he said. Anything lackluster that made it into the show looked like laziness to the team. Miyazaki asked for a lot, but the team’s self-imposed pressure to get Conan right may have asked for more. They had to try.

“I felt that if I gave it everything I had,” Yamamoto said, “Miyazaki-san would be able to put up with me in my current state.”

In the end, Yamamoto not only survived Conan but found meaning in this whole experience. It was different from his days of painting to order, 10 to 10, for shows like Mazinger Z in the early ‘70s. For him, Conan was:

… physically rather than mentally exhausting. I didn’t really dislike it when it was over. I think I learned a lot because I was mentally fulfilled.

With that project done, Miyazaki had proved that he could direct — he was no longer just a talented staff artist with big ideas. And Yamamoto was now a real art director, and a painter to watch.

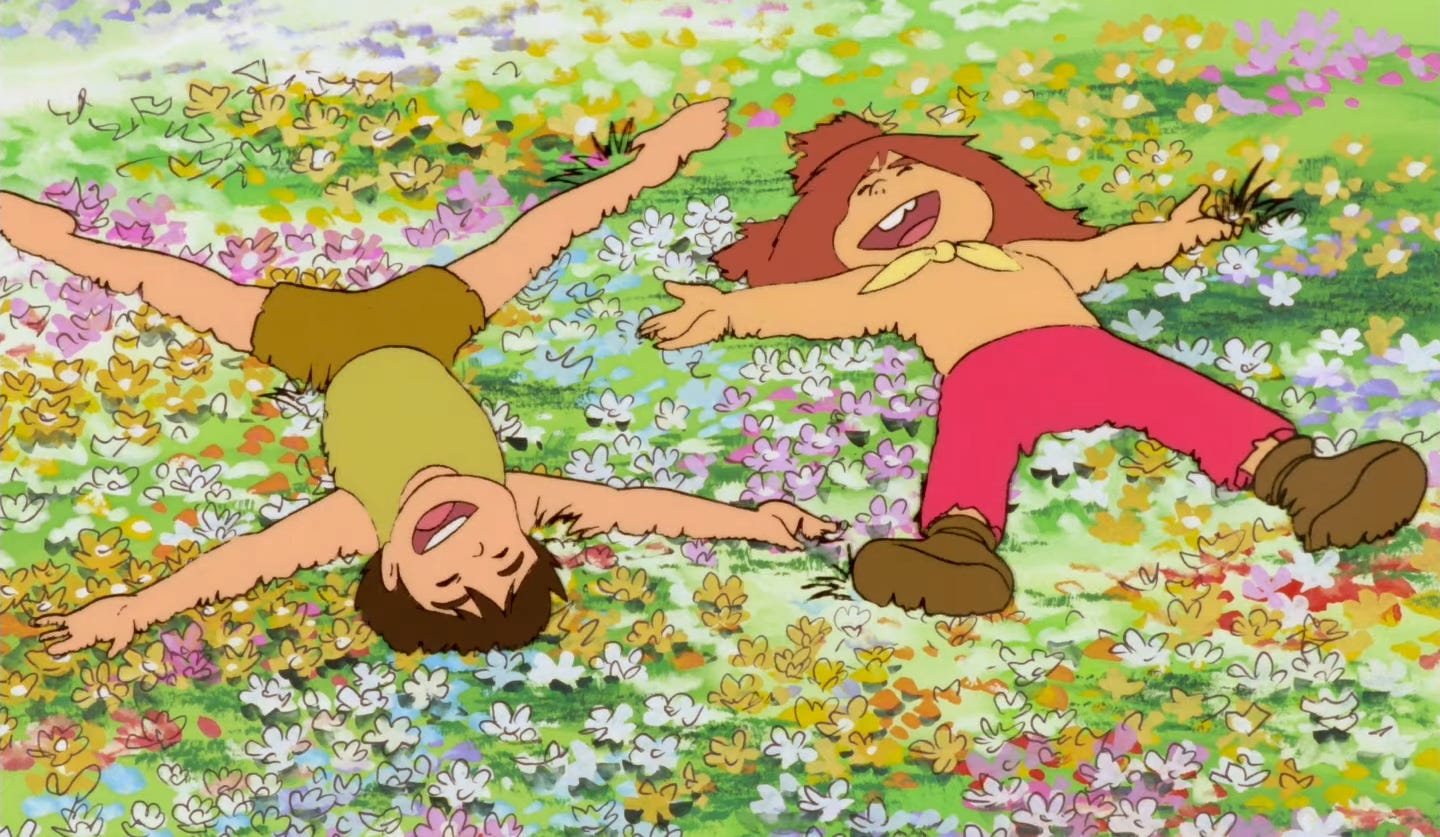

Soon, both of them moved over to Takahata’s Anne of Green Gables (1979). When Miyazaki quit that show and did The Castle of Cagliostro (1979), Yamamoto followed him as a background painter. Then, when Takahata directed his film Chie the Brat (1981), Yamamoto was in the art director’s chair again. Shortly after that, he was back to art directing for Miyazaki on Sherlock Hound.

So it went, even after Ghibli opened in the ‘80s. Takahata came to share Miyazaki’s deep admiration for Yamamoto’s paintings, and used him often. “I have always been humbled by his sincere and precise way of working,” Takahata wrote in 1993. Many non-Ghibli productions (Magnetic Rose, Perfect Blue, Mai Mai Miracle) benefited from those same gifts.

Yet none of it had to happen. Yamamoto landed in the right place at the right time in the ‘70s. Animation wasn’t even necessarily his be-all and end-all. He considered his life’s work to be “One Hundred Views of Goto,” a collection of paintings that he spent a decade creating. He finished it in 2021.

By then, Yamamoto was already a living legend thanks to a career trajectory that could’ve gone differently. He’d stumbled into Conan and, with its whole team, had tried extremely hard to make it work. He was out of his depth. So was Miyazaki, who banked so much of his debut series on a young painter he’d just met.

It could’ve gone differently. But we’re all lucky it went the way that it did.

2 – Worldwide animation news

Animating for a documentary in DC

A couple of months ago, a documentary came out on YouTube — May the Lord Watch. It’s about the rap group Little Brother, whose co-founder 9th Wonder is a beatmaking icon with credits from Jay-Z to Kendrick Lamar. In December, Rolling Stone called it “one of the year’s best music documentaries.” It’s very well made.

The doc is mostly live action — but it uses simple, effective animation to illustrate some of the stories. An outside group in Washington DC, CreativeJunkFood, handled that part. Our thought was: what goes into client animation for a project like this?

The roots of May the Lord Watch go back to 2018. Director Holland Gallagher told us that he met Phonte of Little Brother “in the Uber line at LAX.” This connection started a series of events that ultimately got the doc produced by the outfit Rap Portraits, run by Gallagher and writer Yoh Phillips.

When it came to the animation, a key ingredient was speed. As Gallagher told us:

The animation idea was originally a re-enactment idea, but the scheduling didn’t work out with the actors who were going to play the guys, so actually fairly last minute we brought in Nabeeh [Bilal] and CreativeJunkFood to animate the ideas. They took a look at the cut and ran with it, coming up with many more ideas than we had pitched. We only had about a month left at that point until we needed to lock picture so they were able to pull off what ended up being I think 12 sequences in roughly a month. All of them played great and we kept them all in.

Over email, Bilal explained that he’d worked with three others at CJF (Hannah Churn, Keith Allen Jr. and Gabrielle Moore) to put these scenes together in that one-month span. They needed “to be as efficient as possible.”

Handed the sections to animate, the team did an internal sketch pass, then an animatic to get feedback and lock down the content of the scenes. From there, the final art and movement were built directly over their animatic work.

First and maybe most important, though, was character. As Bilal wrote:

… we started by designing the primary characters — this was key because Phonte had communicated that he wanted something in the style we used in a previous video called Turn It Blue. With MTLW being a character-driven animation, getting the characters right was 90% of the battle.

Given how little we hear about animation in DC, we also asked Bilal about the community and infrastructure that exist for animators there. “I think the pandemic was tough on the animation community from a standpoint of the number of in-person meetups,” he wrote, “but I notice great turnouts whenever people put on animation events, so people are pretty supportive.”

He added:

I also have to shout out professor Tewodross Melchishua Williams at Bowie University because he has been a huge advocate for animators in the DMV area and is always creating opportunities for his students to learn as well as opportunities for local animators to give back and be involved in the community.

You can find May the Lord Watch on YouTube.

Newsbits

We lost Mark Gustafson (64), the co-director of Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio. See Cartoon Brew’s obit for more on his long stop-motion career.

Iranian animator Yegane Moghaddam spoke about her film Our Uniform, currently up for an Oscar.

In Japan, animator Kazuya Kanehisa created a scarily realistic fake commercial. It imagines what an animated iPhone ad would’ve looked like in the 1950s.

Last week, we wrote about Funny Birds, nominated for a César in France. Now its competitor The Forest of Miss Tang (by the director of Funan) is available online in several European countries.

The Mexican feature film Ballad of the Phoenix by Cinema Fantasma (Frankelda) won some financial support for its “development and pre-sale promotion.”

The cool-looking series Pig & Andersen, from Denmark, also secured development funding.

In Japan, the 2023 box office rankings were revealed. The Boy and the Heron placed fourth ($60 million) while The First Slam Dunk ($107.7 million) topped the list.

In America, VFX workers at Walt Disney Studios successfully voted to unionize.

There’s an excellent video interview with Japanese composer Joe Hisaishi about his work on The Boy and the Heron. (Subtitled in English and other languages.)

Lastly, we looked into the ever-morphing animation of Robert Sahakyants, Armenia’s most iconic animator.

See you again soon!

From Takahata’s foreword to Yamamoto’s book Works from Films (フィルムからの言葉, 1993), used a couple of times.

From Miyazaki’s afterword to Nizo Yamamoto Background Painting Collection: Art & Technique (山本二三背景画集 Art & Technique), our source for all of Miyazaki’s comments about Yamamoto today.

Many of these details (along with lots of others) come from Yamamoto’s interview in Nizo Yamamoto Background Painting Collection: Art & Technique.

Yamamoto clarified this in his interview for Future Boy Conan: Film 1/24 Special Issue (1979), published by Anido. One of our most essential sources today.

Yamamoto described Ito this way in this interview.

Miyazaki added a pun to the first sentence of this section in the original Japanese — matching Conan’s title against the word kon’nan, or difficulty.

Live-action Docs with animation are dope! But of course, I am biased. lol. Also, super fan of Yegane Moghaddam. My mom (who is Persian) shared it with me. Such a lovely film and the animation is so creative and refreshing!!!

Great article! I didn't know anything about Yamamoto so it was a fascinating read.

It's mad hearing about how hard the Conan team had to work to get the show to the standard they wanted. Have you covered working conditions in the industry over the decades before? There's this idea that in order to make something great you have to massively overwork, but I'd be interested to know which famously successful projects don't fit that pattern?

As an animator I'm hoping for the successful career, and the work life balance, but maybe that's asking too much.