Happy Sunday! This is our lineup for the latest edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter:

1) How Don Bluth started an animation revolution in his garage.

2) The animation news worldwide.

A tidbit before we start — a legal YouTube channel called Filmy česky has been sharing classic Czech animation. That includes the funny and very weird Cleansing Bath by Václav Bedřich, and (deeper in its catalog) the even stranger Crabs.

With that, here we go!

1 – An accidental uprising

Studying the art of animation has never been easier — even if you don’t go to school for it. Blender is a powerhouse, and the software that Studio Ghibli used to make Spirited Away has been free for years. On the internet, all the world’s animation is at your fingertips. And online tutorials break down every part of production.

Today, popular animators like Ian Worthington and Preston Mutanga are teaching themselves.

So, it’s hard to picture Don Bluth’s situation. Back in the early 1970s, he was the up-and-comer at Disney. Walt had died a few years before, and the famous Nine Old Men were getting older. The studio still trained new talent — but Disney’s classic filmmaking had started to slip away, right alongside the veterans who’d pioneered it.

It was a scary time. The reins hadn’t been passed at Disney quite like this before, and much had already been lost since the studio’s best years.

As Bluth remembered, older technical tricks like the “shadows or the reflections or the double passes through the camera” were “evaporating before our very eyes.”1 The problem was bigger than that, too. Bluth and many of the other young trainees didn’t know how to make a movie, and they weren’t sure how to learn. According to Bluth’s colleague Gary Goldman, “We didn’t even know what questions to ask.”

“We were learning to animate,” Goldman explained. “We were learning to in-between, clean up … and we said, ‘Wait, there’s so much more we need to know.’ ”

That included writing, scene planning, editing and more. Even the Nine Old Men had “forgotten” much of what went into Disney’s older films, said animator John Pomeroy. Speaking to the press in the ‘70s, Bluth described this unsettling moment:

I was watching The Sorcerer’s Apprentice part of Fantasia recently and I marveled to Ken Anderson, one of the veterans, about the water. It was so transparent. So wet. I asked Ken how they did it. … The man who created that water is long gone, Ken told me, and no one ever did get around to writing the process down. “Nice, isn’t it?” he said. “We’ve never gotten it that way again.”

If that happens in too many areas, the whole heritage is gone.2

But how to stop the decline? That was the thing — the new recruits weren’t even allowed to use the studio’s tools to rediscover techniques through trial and error. As Bluth said:

Disney was a union house. We couldn’t touch any of their equipment to experiment … We couldn’t even plug the Moviola in to look at what we were doing. Or use a cutter, or anything, because it was all union. And we were not in that union.

Management said that the Nine Old Men would retire within five or six years. Bluth, Goldman and the rest would soon fill their shoes — with only a rudimentary sketch of what the masters once knew. They needed, and wanted, to learn faster.

Hoping to bridge the gaps in their knowledge, Bluth started a side project. An independent cartoon made with independent equipment. In his garage.

The idea to make a garage film didn’t stem from a desire to escape Disney. “We were actually very enthusiastic about working at Walt Disney Productions, almost obsessive about it,” Goldman noted. What they needed was a space to learn — by doing, by trying things and by making lots of mistakes.

The Disney studio couldn’t offer that, and so the garage became their school. Bluth called it their “sanctuary.”

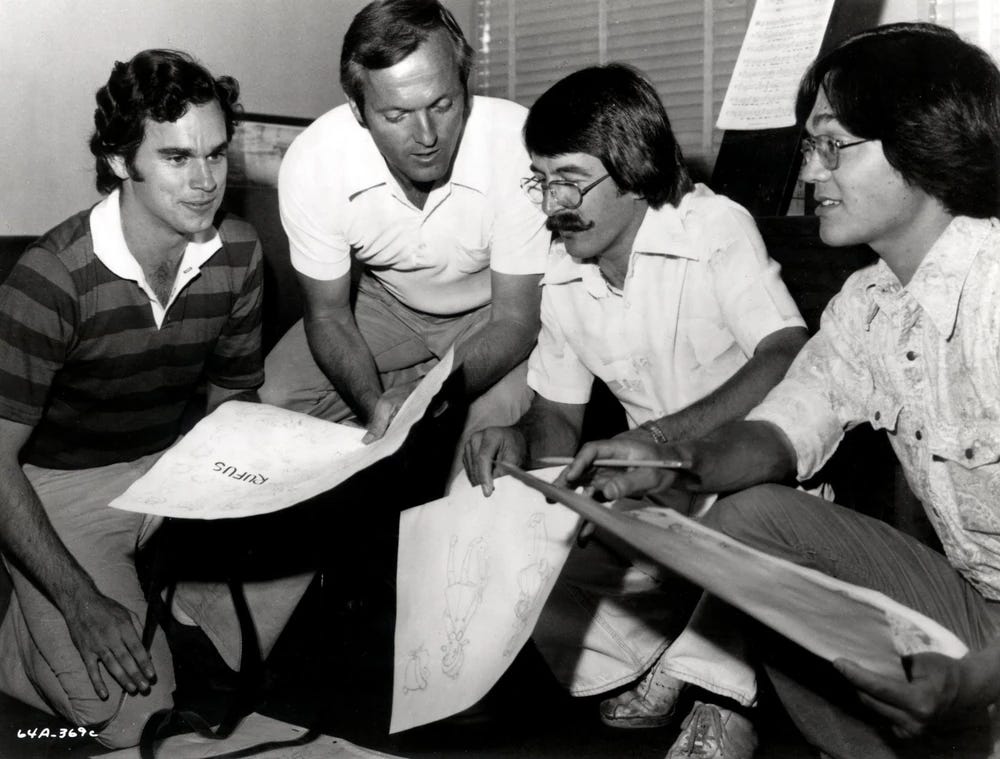

According to Goldman, Bluth already owned a Moviola and an editing bench that he used to study “old 16 mm Warner Bros. animation reels.” Gathering a few more production tools, a small team formed in 1972. They wanted to make a short called The Piper, based on a long limerick written by Bluth’s brother.

Bluth, Goldman, Pomeroy and a rotating cast of others spent years on The Piper alongside their Disney work.3 The de facto head of Disney’s animation branch since Walt’s death, Woolie Reitherman, supported their efforts to learn.

And they learned quite a bit, often the hard way. They ended up storyboarding 20 minutes of The Piper and animating around four (watch a few seconds here). In 1975, they brought in the legendary John Lounsbery to assess it. Bluth:

It was excruciatingly painful, actually embarrassing to watch with one of the Disney animation masters sitting in my living room. It was then that we realized that the story wasn’t appropriate for a short; too much information in too short of a time … The very next weekend we decided to scrap The Piper and chose something simpler.4

That simpler project became Banjo the Woodpile Cat. The idea was based on a kitten from Bluth’s childhood. They planned to make the film in a year — which seemed doable enough when work began in March 1975.

Banjo wouldn’t pull across the finish line until December 1979.

Banjo turned into “an underground animation campus,” in Pomeroy’s words. The learning environment proved magnetic — many Disney staffers came through to work part-time. Animator Linda Miller remembered that she “wanted to learn more about filmmaking … and it also seemed more exciting than the projects that Disney was working on.”

Looking back, artist Vera Pacheco was effusive. “I was able to learn things that Disney didn’t even offer training for at the studio,” she said. That included inking and painting, animation checking and even “how to fill out an X-sheet.”

Disney’s people showed up at Bluth’s garage after work and on weekends. “They would teach animation to any artist interested,” animator Dorse Lanpher wrote. A number of women from the studio got involved — around four minutes of Banjo were animated by Linda Miller, Heidi Guedel, Emily Jiuliano and Lorna Cook. If someone wanted to learn, Bluth said, they “never turned anyone away.”

This was a very-1970s guerrilla production. Before it was over, Goldman had stolen rain and snow overlays from Disney’s garbage. A young Glen Keane created the sound effects for a truck’s exhaust pipe. Bluth, Goldman and Pomeroy animated most of the film, but Bluth’s main memory of Banjo was mixing cel paint by his swimming pool.

Gradually, the production (and the rows of work desks) outgrew Bluth’s garage and took over his whole Culver City home. Guedel recalled that Bluth “literally lived with only his own single bed and a dresser in his small bedroom” — every other space “was filled with animation equipment.” During the busiest periods, Banjo artists slept where they worked and sleeping bags dotted Bluth’s house.

The storyboards for Banjo were all Bluth’s. He handled them in his detailed style — trying to create a clear blueprint for the team. John Pomeroy built on these sketches with ink and sometimes color. A single Bluth drawing could act “as layout, pose test for the animator and then eventually a … color sketch for background and lighting and effects,” as Pomeroy said.

While they learned about film production, Bluth and his colleagues also studied the storytelling rules that had once powered Snow White and Bambi. In his autobiography, Bluth made mention of “dog-eared books about screenwriting,” and of discussions about conflict, motivations, character flaws, themes.

All of the learning quickly started to pay off. The group went into The Rescuers (1977) energized, with “an eye focused on the story, not merely the quality of the animation,” according to Bluth. When he got the co-director role on Pete’s Dragon (1977), he consistently relied on lessons from Banjo. Pomeroy did the same as an animator on Pete’s Dragon, solving complex problems by thinking back to his work at Bluth’s place.

Not everyone at Disney, though, was amused by Bluth and the Banjo project. Feuds formed at the studio, and some were derogatory toward the “Bluthies” in the garage. The younger set from CalArts, like Brad Bird and John Musker, shared Bluth’s unhappiness with Disney — but they didn’t get along with him, either.

Bluth was a traditionalist and a charismatic figure. To some CalArts upstarts, he may have resembled a cult leader, and they called him “arrogant, self-serving and an elitist.” They were on Bluth’s team when he directed The Small One (1978) at Disney, and the fighting was explosive. The area of the studio occupied by the CalArts people came to be known, proudly, as “The Rat’s Nest” — after Bluth described it that way.5

In the late ‘70s, Bluth went public with his thoughts on the Disney youth. “The new bunch were arrogant, they refused to listen and got mad if you tried to press them. You’d explain a drawing to them, then look around and see they had wandered off,” he told the papers. Neither side could understand the other.6

Adding to the trouble, Banjo itself was dragging on and on. Bluth again:

About four years into this … we wondered if we would ever recoup our investment of time and money. Then, in late 1978, we thought, what if we took it to Disney, they might agree to buy it and let us finish it there during regular work hours.

Disney wasn’t interested. Combined with Bluth’s bad experience on The Small One, the writing was on the wall. Only some of the younger people at Disney wanted to follow his lead — and there was a sense among the garage artists that Disney’s management didn’t care to implement most of the lessons from Banjo.

“All of our learning is only going to do us any good,” Pomeroy remembered thinking, “if the higher-ups will accept what we’re trying to make happen.”

Much has been written about the moment when Bluth, Goldman and Pomeroy quit Disney in September 1979. It was a huge event in the animation world, even hitting the national news. The late Michael Sporn once wrote, “I can’t exaggerate the excitement this caused in the ‘young’ animators at the time — even 3,000 miles away.”

Quite a few who’d learned at Bluth’s school-studio came along, including Disney’s entire staff of women animators. At Disney, Bluth told The New York Times, women were rarely allowed to advance past the assistant role in animation. Given a chance to learn more, figures like Lorna Cook became forces of nature.

Banjo made the departure possible — and not just because it taught the team how to make a movie. Outside investors had asked Bluth and Goldman, while they were at Disney, if they’d be willing to quit and do their own film. Bluth only had to prove he could make one. He showed them Banjo, which was “about 90 percent animated and about 70 percent in color,” and got handed millions to finish it and to make The Secret of NIMH.

At the newly official Don Bluth Productions, Banjo had a nail-biting final crunch. It managed a limited run in California during December 1979, and later aired on television. Bluth has readily admitted that the film isn’t a classic. But it did give him and his team the skills to craft one.

After four and a half years of learning on Banjo, they had a hunger to make a truly great feature film — and they finally knew how to do it. Even Banjo’s flaws were fuel, in the end. “What we were not able to do on Banjo and we were learning on Banjo,” Pomeroy concluded, “we carried on through The Secret of NIMH.”7

2 – Newsbits

In Canada, Icon Creative Studio is trying to unionize. This comes at a time of huge union wins in North American animation, including the new one at DreamWorks.

In Russia, a group called Vidachestvo is tracking down and scanning prints of old Soviet cartoons in HD, then dropping them on YouTube. Among them are a first-of-its-kind 2K upload of The Tale of Tsar Saltan (1943) and, a few weeks ago, a 2K version of the classic oddity Hen, His Wife (1990).

Cartoon Brew has started a weekly Friday livestream — revealing in the latest one that the American film Coyote vs. Acme is not yet dead. (There were some kind words about our newsletter, too, which we’re very grateful for.)

Also on Cartoon Brew, we enjoyed this week’s write-up on Bobe Cannon, the great (greatest?) American animator.

In China, the box-office success of The Boy and the Heron continues, despite online controversy over the film’s bewildering story. It’s earned more than $92 million in the country as of this writing, per Maoyan.

The stop-motion studio that revived Clangers in England is being liquidated. “Unfortunately,” said a spokesperson, “over the last 12 months the number of projects being greenlit by broadcasters around the world has been severely cut.”

Japanese animator Kazuya Kanehisa talked to Tokyo Sports about his fake ads for products like ChatGPT and the iPhone, done in the style of mid-century cartoons (watch). Kanehisa says he’s planning a new video “based on a fictional, long-running anime,” tracing the changes it undergoes across the decades.

Also in Japan, animator Hidekazu Ohara shared some rare pieces of his concept art for Katsuhiro Otomo’s Cannon Fodder.

Vaibhav Studios of India won two awards stateside for Return of the Jungle, its long-awaited feature.

As the French film Chicken for Linda! hits America and Japan, its directors have had a roundtable discussion with Sunao Katabuchi (who loves the film), and GKIDS has shown off the special recording process used for the voices.

Lastly, we looked into the development of animator Kunio Kato (The House of Small Cubes) over the decades, through his artwork.

See you again soon!

These quotes from Bluth, and a good deal of the article’s other quotes and information, come from extras on the Banjo the Woodpile Cat DVD.

From the Dayton Daily News (November 28, 1978).

As John Cawley wrote in his book The Animated Films of Don Bluth, loose experiments in the garage from 1972 onward gave way to The Piper over time:

These were initially exercises to relearn some of the techniques of the past. Using their salaries and exercising their stock options they purchased a number of pieces of equipment including a Moviola.

These weekend workouts saw almost everyone at the Disney studio drop by. If they felt invigorated, they stayed. If they wanted to go other directions they never came back. Don saw this as a good weeding-out period, helping him locate talent that agreed with his vision.

From Bluth’s interview in the second volume of On Animation: The Director's Perspective.

For more details on this conflict, see the books Pulling a Rabbit Out of a Hat: The Making of Roger Rabbit, Directing for Animation and Somewhere Out There.

See The Lincoln Star (October 18, 1979).

Today’s lead story is a revised and expanded version of an article we first ran on June 14, 2021.

The Secret of NIMH is a classic. One of my favorite movies. A brilliant piece of work.

Great article! It's fascinating hearing about the conflicts behind the scenes of the Mouse. Wild to me that they were so disinterested in training up the next generation of animators. This fills in a big piece of the puzzle of how Don Bluth's films came to be and what his conflict with Disney was about.

It's honestly somewhat reassuring in a way that it took four years for Bluth and co to put together the skills to make a film, even on a solid background of drawing and animation knowledge. Makes me feel better about how long it's taking me ^^'