Happy Sunday! We’re back with another issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. This is the lineup today:

1️⃣ Diving into The Hole (1962), an anti-nuke gem by Faith and John Hubley.

2️⃣ The animation news of the world.

New here? You can sign up to receive our Sunday issues for free, right in your email inbox. Join 10,000+ other readers:

And now, we’re off!

1: Inside The Hole

It’s no secret that we live in dark times. Since Russia began its brutal invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the world situation has grown more and more precarious.

For a year, talk of World War III has hung in the air. Russian officials threaten nuclear attacks almost weekly. The idea trends often on social media. You get numb to it — but the worry doesn’t go away. After all, periods quieter than ours have brought nuclear close calls. The only world leader known to have activated a nuclear briefcase wasn’t a Cold Warrior: it was Boris Yeltsin, during the obscure Norwegian rocket incident of 1995.

People have understood for decades that it only takes one radar glitch, one bad decision. The biggest risk of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 — the closest the Cold War ever came to turning hot — was that someone would make a mistake. When they did, annihilation nearly followed.

Those risks were on the minds of artists Faith and John Hubley that same year. In protest, the two animation legends made one of their best films: the Oscar-winning classic The Hole (1962).

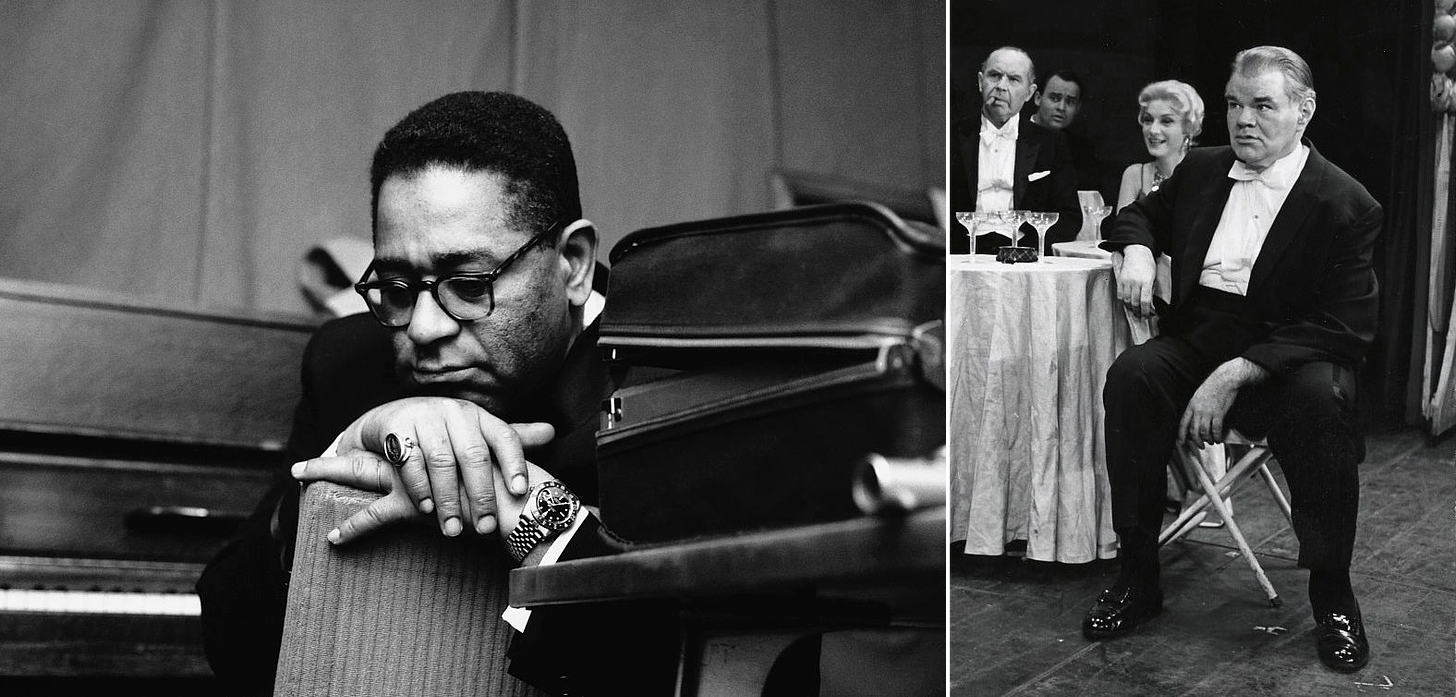

The Hole is a beautiful piece on a terrifying subject. It stars two construction workers, voiced by jazz musician Dizzy Gillespie and actor George Mathews, as they mull over a question: “what if an accident happens?” The Hubleys present a film that, even in its gorgeous execution, demands an alternative to the worst-case scenario it ponders.

When they married in 1955, Faith and John Hubley made two vows. They promised “to eat dinner with the children and to make one independent film a year.”1 John downsized his profitable TV animation studio, Storyboard, into a small New York operation focused on art. The couple’s indie films began to pop up every year.

Soon, their piece Moonbird (1959) won an Oscar, the first for an independent cartoon.

Hubley animation was different, in tone and style and topic, from anything else at the time. It expressed their views and even their family life in intimate detail. “We try to keep the staff at half a dozen [per film],” Faith once explained. “This work is highly personal and it suffers terrifically if it gets farmed out to strangers.”2

Although the Looney Tunes style stayed popular, Hubley films helped to carve a niche for animation beyond gags. In 1963, one critic cited “the leading role of this husband-wife team in the development of the serious cartoon.” The Hole inspired that remark.

Which isn’t to say that The Hole isn’t funny. It is. But it tackles global nuclear war with weight, at a time when many believed that obliteration lay right around the corner. It’s a 15-minute experience, and improvisation sits at the heart of it.

The film was developed from an audio recording of Dizzy Gillespie and George Mathews. Gillespie was a close collaborator of the Hubleys’ — they were fans of each other’s work. In his memoirs, Gillespie called it a “mutual admiration society.” He once told a reporter how The Hole came about:

I went to this studio in New York to cut the tape and met Mathews. I had seen him in so many movies I felt like I knew him well. I started over to hug him and then thought — “Damn! Diz, you never met this guy!” The producer John Hubley said, “You two are in a hole, digging.” We just took it from there — no script.

The inspiration for The Hole came from two sources. One was a noisy Con Edison construction crew, working beside the Hubleys’ New York office on Riverside Drive and 87th Street. John recalled “a pneumatic drill right outside the window, busting up the sidewalk.” He went out to observe — sketching the men and speaking with them.

The second source was distributor Brandon Films, which contacted the Hubleys about doing a film on “the danger of a nuclear accident.” This idea got mixed with John’s studies of the workers. So, the Hubleys brought in Gillespie and Mathews to record.

As we’ve noted a few times lately, Faith and John Hubley liked to base cartoons on improv. They would record hours of audio on tape, with a few guidelines to keep the conversations on track — and then edit it all down into dialogue. They’d had success with this style in their I Want My Maypo TV ads, and they’d reused it in Moonbird.

But those recordings had all involved children, and The Hole’s cast is entirely grown up. The results are different, and fresh. Gillespie loved the process — he and Mathews sank into their roles and let the conversation develop. They “talked about the world situation, world government, and all those things,” Gillespie remembered.

It’s a mix of everyday smalltalk and, as time passes, the ever-present fear of nuclear war. Mathews’ character is convinced that the weapons won’t be used — true accidents don’t happen. Gillespie’s character sees the danger. There’s a real naturalism to the dialogue, and it’s packed with highlights. Gillespie’s cry of “I am the government!” is one of the all-time great moments in a Hubley cartoon.

With the tapes in hand, John and Faith set out to construct a film. They assembled another of their small teams, doing a lot of the work themselves. And they leaned into the forward-thinking techniques that had powered projects like Moonbird.

Hubley cartoons were always trying new things. “They violated all the rules,” recalled animator Bill Littlejohn, who worked on The Hole. Hubley animation is rife with visual ideas that no one else used because they weren’t supposed to work. According to Michael Sporn, who spent years at the Hubleys’ studio, The Hole features:

… what they called the “resistance” technique. They first colored the characters with a clear [wax] crayon. Then painted watercolors on top of that. The crayon would resist the watercolor and a splotchy, painterly style developed.

Like with Moonbird, the artists drew and colored The Hole on paper, rather than cels. This caused a problem: cels are transparent, but paper isn’t. To overlay the wax-and-watercolor characters onto the oil-paint backgrounds, the team had to use a filming trick.

Each character drawing was surrounded with black oil paint, then filmed straight over existing footage of a background. Moonbird had used the same technique. “The cameraman, Jack Buehre, would shoot the background,” Sporn wrote, “then roll back the film and shoot the blackened characters as a double exposure.”

That isn’t the only camera trick here. Mesmerizing passages of The Hole go by with little character animation — the Hubleys illustrate parts of the conversation with more of their lovely background art, brought to life with odd exposure effects.

Even more than Moonbird, The Hole feels like a painting from the era, in motion. It’s all rich, ethereal textures. Sporn once noted that “the abstract expressionists ruled” this era of the Hubleys’ work, and you can feel it here. Jackson Pollock’s influence is all over this film.

As one critic wrote after The Hole’s release, “This is a long way from Moonbird, even further from [John] Hubley’s UPA days and eons away from Disney.”

The Hubleys hired only two artists to animate The Hole. Littlejohn, a frequent Hubley collaborator, was the lead animator. Later in life, he remembered animating the dance of the Gillespie character “straight ahead,” one frame after another. That action, like so much of the animation in The Hole, is full of loose energy. It’s pure motion.

Gillespie later said to Littlejohn, “Man, I’m glad you did that section yourself, because I can’t dance!”

While most of the animation credit on The Hole goes to Littlejohn, animator Gary Mooney also contributed. At the time, Mooney described the project in a letter to his father:

The Hole is an anti-war film, done in a different way. Some people won’t like it, some won’t get it, some will love it, some hate it even, others won’t give a damn. I think we have a potential Oscar winner, because it’s original in the cartoon field, it’s beautiful, clever and weird, all at the same time.

Mooney was right: it is a different kind of anti-war film. It’s one that suggests rather than shows, that avoids being either maudlin or nihilistic. Gillespie’s singing at the end is mournful. It’s not hopeless.

He was correct, too, that not everyone would love it. Even at the time, there were a few doubters. It’s by no means a traditional cartoon — that’s the magic of it.

And, finally, Mooney was right that The Hole would triumph at the Oscars. In February 1963, it became John and Faith’s second cartoon together to nab a trophy. Other winners that year included To Kill a Mockingbird. Like that film, the Hubleys had done something extremely topical, and far removed from rote studio formulas.

Not long after he accepted the award, John said this to a reporter:

Sure, this was my third Oscar, but honestly my blood pressure went up 300%. … There isn’t much I remember after the first few words.

The victory was yet another blow to the dominance of the major animation studios. As with Moonbird, the Hubleys financed The Hole out of pocket — barring a small infusion from Brandon Films at the start. An indie cartoon had beaten the likes of Warner and Disney.

Unfortunately, despite that accomplishment, the film wasn’t widely seen. “The Hole […] never achieved major distribution,” Faith wrote in 1999. “Obviously, the Academy enhances prestige but not material support.”

Even so, the Hubleys had made their point. The Hole is a statement as relevant today as it was in 1962. It’s both an explicit warning and an implicit alternative. Each lovely facet to The Hole appeals, quietly, to the humanity of humanity. It asks for more art. It demands less war.

This is a revised reprint of an article that first ran in our newsletter on March 3, 2022. It was exclusive to paying subscribers then — one year later, we’ve made it free to all.

2: Newsbits

We lost Disney icon Burny Mattinson (87), who started at the company in the ‘50s when Walt Disney himself was still alive — and actor Shōzō Iizuka (89), whose legendary career included projects like Paranoia Agent and Millennium Actress.

In Japan, the stop-motion samurai tale Hidari has a pilot coming March 8 on YouTube. The trailer blew our minds this past week.

In China, a sequel to the film I Am What I Am has passed government approval. The original was about the tradition of lion dance — this new one focuses on martial arts.

Artist Parker Machemer translated a great tidbit from Japan — a 1989 Studio Ghibli recruitment pamphlet, written and drawn by Hayao Miyazaki. Check out Miyazaki’s 1980 notes on animated running as well.

The Ukrainian feature Mavka: The Forest Song, completed during the war, had its premiere on March 1 in Kyiv. Meanwhile, Ukraine is in the spotlight at Cartoon Movie in France — an important event where studios land funding and distribution partners for animated projects.

The Greek festival Animasyros has opened its annual call for submissions.

In South Korea, The First Slam Dunk has dethroned Your Name to become the most successful anime film in Korean box-office history. It’s earned more than $30 million in the country.

Studio Eeksaurus of India dropped a behind-the-scenes teaser for its animated project about philosopher Sri Aurobindo.

Argentinian animator Juan Pablo Zaramella hit the Oscar shortlist this year with his film Passenger. Now, Radix reports (with a cool still) that he’s prepping a stop-motion feature called I’m Nina, about a rat who finds herself in a world of rabbits.

The French TV special Funny Birds, one of our favorite works of animation from the past few years, will reach theaters in France this April as part of an anthology. (Funny Birds also won a few awards at Anima in Brussels.)

Lastly, on Thursday, we wrote about Faith and John Hubley’s 1968 stunner Windy Day.

Until next time!

From the website for the PBS documentary Independent Spirits, about the Hubleys.

From the interview with Faith and John Hubley in The American Animated Cartoon: A Critical Anthology, which we use a few times. Other sources include the Philadelphia Daily News (May 7, 1963), the Los Angeles Times (May 3, 1963), The Salt Lake Tribune (April 11, 1963), this article and Michael Sporn’s comment here.