Welcome to another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter! Thanks for joining us. Here’s a quick rundown of what we’re doing this week:

One — a look at The Snow Queen, Miyazaki’s “destiny.”

Two — animation news from around the world.

Three — the retro ad of the week.

Four — the last word.

If you’re new around here, now is a great time to sign up — it’s free and takes zero effort. Catch our newsletter in your inbox every Sunday:

With that out of the way, let’s begin!

1. Miyazaki and The Snow Queen

Disney has exerted a colossal influence since the early days of animation. Contrary to popular belief, though, it hasn’t been a universal influence. Certain countries looked to other guiding stars. In the early Japanese anime of the ‘50s and ‘60s, you see an inspiration at least as large as Disney — Soviet animation.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the career of Hayao Miyazaki, who once claimed to “hate Disney’s works” — even raging that they “show nothing but contempt for the audience.”1 He became an animator at Toei Doga in Tokyo after seeing the studio’s Panda and the Magic Serpent (1958), but he quickly grew disillusioned and almost quit. That is, until a Soviet cartoon changed his mind in 1964. It was The Snow Queen.

“Had I not one day seen The Snow Queen during a film screening hosted by the company labor union,” Miyazaki later wrote, “I honestly doubt that I would have continued working as an animator.”

He became obsessed. After a friend recorded the film’s audio on tape at one screening, Miyazaki said that he “borrowed it and listened to it over and over again at work.” Eventually, he wore it out. When the Ghibli Museum re-released The Snow Queen in 2007, its poster carried a blurb from Miyazaki — “my destiny and my favorite film.”

But what was this magic within The Snow Queen that inspired Miyazaki, that energized him enough to continue in animation?

It came from a team of Russian masters — some proven, some just starting. There was Leonid Shvartsman, the illustrator who would design Cheburashka. There was Fyodor Khitruk, the animator who later remade Russian cartoons from the ground up. These greats and others crafted The Snow Queen in Moscow, at the state-owned animation workshop Soyuzmultfilm.

It began in the mid-1950s. The war was over, Stalin was gone and hope for Russia’s future filled the air. It was “the brightest and most joyful time,” as Shvartsman put it.

Shvartsman had joined Soyuzmultfilm in 1951, art-directing The Scarlet Flower and The Golden Antelope alongside Alexander Vinokurov. At the helm of both projects was Lev Atamanov, whom Shvartsman called “fabulously talented” and “a most amiable man.”2 They built from fairy tales, which were easier to sell to the state censorship board. Hence The Snow Queen, a Hans Christian Andersen story.

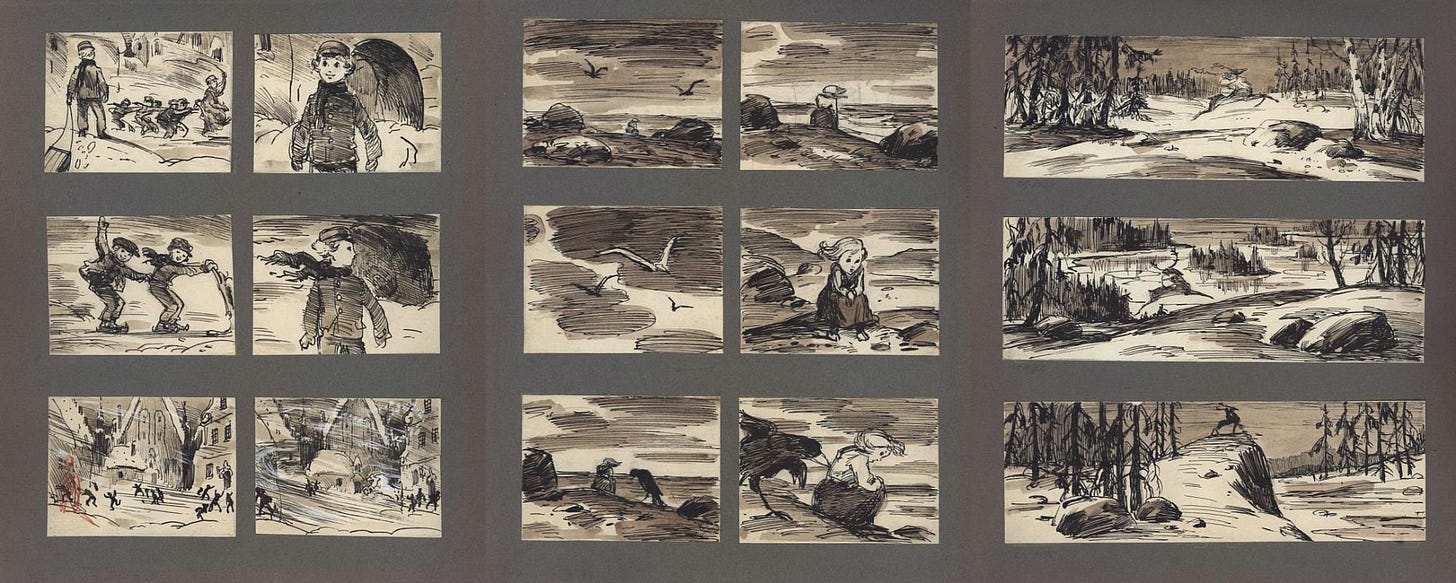

Atamanov, Shvartsman and Vinokurov began the project in their usual way — with extensive research. The Iron Curtain barred them from Andersen’s home country, though, so they used the Baltics as a substitute. Per Shvartsman:

Having no opportunity to go to Denmark when starting our work over The Snow Queen, the three of us went to Latvia and Estonia for a fortnight — just to rove along the Riga, Tallinn and Tartu streets, absorbing their architecture, letting their atmosphere penetrate our visual memory, making countless sketches and photos, discussing and debating over each tiny trait of the future images.

The Snow Queen would be a culmination and a furthering of everything Soyuzmultfilm knew. In production for over two years, it grew to a vast 70-minute runtime uncommon in Soviet animation. Visually, the team built on its usual Disney-inspired style — a blend of realism and storybook illustration. The Snow Queen pushes this look forward in bold, new ways.

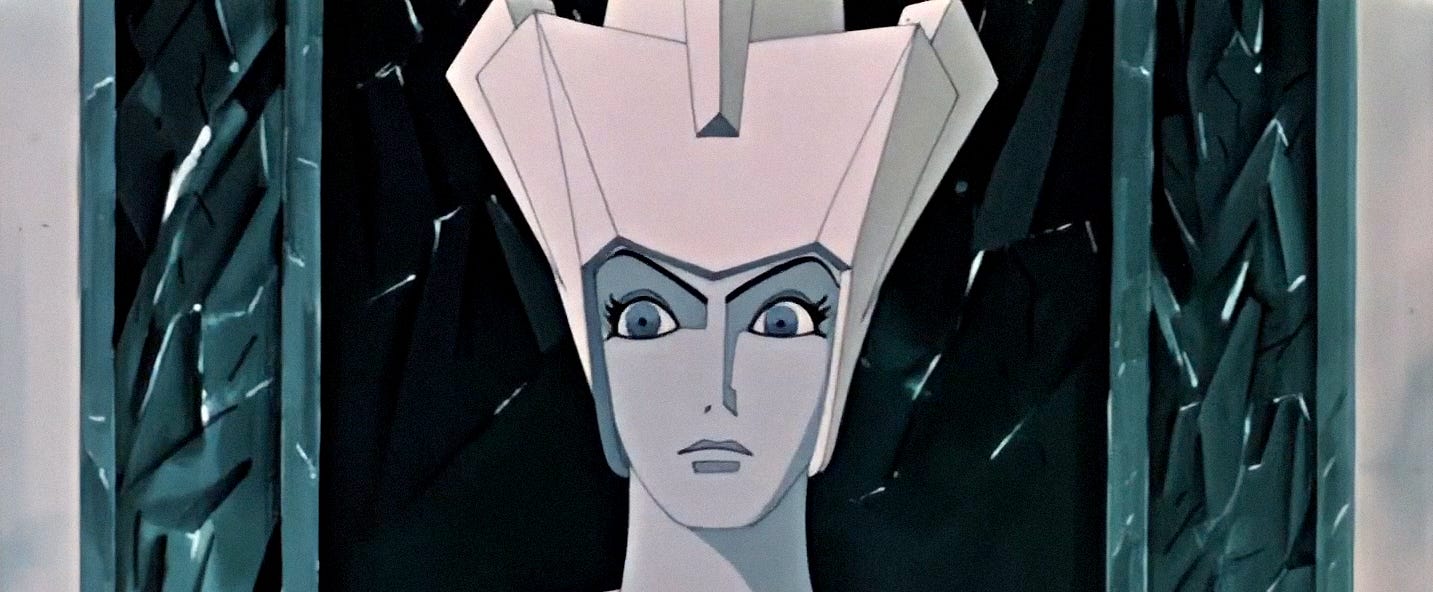

One part of it lies in the motion. In the Stalin era, animators often rotoscoped from live footage. This trick appears strategically in The Snow Queen — for example, actress Maria Babanova as the Queen. Many times, though, it doesn’t appear at all. Fyodor Khitruk reportedly animated all of the character Ole Lukøje without the technique, which he later called “the most significant and successful” animation of his career.

Without rotoscoping as a crutch, the team aimed for pure expressions of character. That’s the core of The Snow Queen — and not only in the movement. The cast was meant to distill and clarify real life. Atamanov once wrote that animation’s strength and “genuine realism” lie within “wide generalization, careful selection and, most importantly, grotesque exaggeration.” It’s art that pinpoints and intensifies the world.

“I was looking for the ideal nature of each character,” Shvartsman explained. That included the Little Robber Girl’s “straightforwardness and courage,” and Gerda’s “self-denial and spirituality.”

These traits of Gerda’s made an impression on Miyazaki — particularly in the scene where she offers her shoes to a lake (as seen in the clip below). She journeys through the world with relentless dedication, losing “more and more things.” In the process, Gerda’s spirit transforms the people she meets.

Miyazaki has called the moment when Gerda changes the heart of the Little Robber Girl the climax of The Snow Queen, even though it happens long before the end. The girl frees all of the animals she’s trapped, Miyazaki said, and then “everything is purified.” Here’s how he explained it:

[W]hen she hears Gerda’s story she realizes that, unlike Gerda, she has no one to love. She tried to lord it over all sorts of things, but she realizes that what she really wants is not to keep animals in cages and tied up in ropes, but to love someone. That’s why she says, “Get out of here!” to her animals when she frees them. She’s a robber girl, and it’s the only way she knows how to show her love.

It’s not an overstatement to say that Gerda, the Little Robber Girl and scenes like these have echoed throughout every film Miyazaki has worked on. These characters, in their complexity and strength, inspired everyone from Hilda in Horus: Prince of the Sun to Kiki in Kiki’s Delivery Service. One book even makes the case that Princess Mononoke is essentially an interpolation of The Snow Queen, with San as the Little Robber Girl.

There are a few ironies here. Despite Miyazaki’s hatred for Disney, he’s based his career on a Disney-inspired film — Bambi changed Shvartsman’s life. Another is that The Snow Queen, despite being Soviet, espouses none of the communist views that powered Miyazaki’s own early work. (Miyazaki only abandoned Marxism in the ‘80s, deciding that the “idea that someone’s right just because he’s a worker is a lie.”)

Then again, Miyazaki has always been trapped by circumstances like these. In the ‘80s, near the end of an essay where he explained his love of The Snow Queen, he wrote this:

I tell people I hate professionals, but I know that in the workplace I evaluate people on the basis of their talent alone. I say that I don’t want to talk about animation, but here I am, talking about it all the time. I yell about how it would be better if Japanese anime just disappeared from the face of the earth, and then I turn around and worry about my animator friends who don’t have any work.

You can watch The Snow Queen, with optional English subtitles, on YouTube.

2. News around the world

Promising signs for Taiwanese animation

Taiwanese animation has had a rough few decades. A Chinese-language interview last month with Richard Metson, a veteran artist from Taiwan, drives that point home. In his words, Taiwan doesn’t actually have an animation industry — teams often disband after finishing projects, funding is scarce and the potential audience is small.

Still, this week brought promising news for animation in Taiwan. The big highlight was the premiere of Omi Sky on the channel PTV. Funded in part by the government’s Ministry of Culture, it’s an educational drama series for children, with an intriguing look. The story is surreal:

In a future world following the demise of mankind, the Earth is covered by a mechanical sky. Omi, who lost his memory, falls from the mechanical sky to an abandoned spacecraft, where he encounters a new friend of the Mechanical species, Fish Box. They use their scientific knowledge to solve problems and fix the spaceship so they can go back to the mechanical sky.

Omi Sky comes on the heels of PTV’s well-regarded Brave Animated Series, according to the China Times. The government financing that produced Omi Sky is planned to support more animation from PTV — one high-up at the channel expressed hope that Taiwanese children’s animation would continue to grow.

In other news, the Venice Film Festival selected a Taiwanese stop-motion film this week. Called The Sick Roses, it’s a VR project with a dark, strange style. Production lasted 14 months, and was delayed by several earthquakes that jostled the camera.

Graduation season in China, recapped

A flurry of animation by Chinese students arrived during the last two months. In other words, it’s graduation-film season. This is the final moment of independence for many of these animators. China offers little support to indie animation — most animators have no choice but to work for companies after they leave school.

In what’s become an annual tradition, Wuhu Animator Space has rounded up hundreds of student projects from across China, separated by university. Recently it’s covered the classes of 2021 at Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts, Jilin Animation Institute and more. Wuhu’s selection is massive — way too large to summarize here. For anyone interested in the next generation of Chinese talent, though, it’s worth a look.

Best of the rest

This week brought news that Arthur, one of America’s longest-running and best-loved children’s cartoons, will end in 2022. It seems production was halted in 2019.

In China, Green Snake made a splash at the box office, amid a somewhat dry season. The sequel to the popular White Snake is expected to earn $77.5 million during its run.

Another week, another interview with Zhou Fang Yuan of China about her wonderful student animation Kaleidoscope. This one includes her storyboards, reference photos and more.

The festival that wants to solve the crisis-level conditions for independent cartoons in China, Feinaki Beijing Animation Week, is underway again. It’s also running online this year through August 26.

The premiere date for Summit of the Gods, the French film based on Jiro Taniguchi’s manga, has been moved up to September 22.

The French animation Migrants picked up a BAFTA Student Award this week. We caught it at the recent Bay Area International Children’s Film Festival — it left an impression.

MyAnimeList has made big moves since February, when Japanese companies like Kodansha invested heavily. This week, the advertising firm Dentsu, known for its close ties to the Japanese government, poured more money into it.

3. Retro ad of the week

“It’s a Fo-o-ord!” With these three words, John Hubley’s studio Storyboard took over America in the 1950s. They appeared in a series of Ford Dealers ads, which started hitting the airwaves in ‘54. By the next year, Billboard was calling the series “probably the most public-accepted commercial in the history of radio and television.”

It’s hard to express just how big Hubley’s Ford ads were. For perspective, consider that the ad industry voted them the best, most effective campaign of 1955. That doesn’t give you their cultural clout, though, as one journalist tried to convey at the time:

At Judy Garland’s TV debut, the “star” that drew the most applause from the studio audiences was [Ford’s] new 30-second cartoon commercial that ends “It’s a F-o-rrd!”

These animated commercials have become one of the biggest entertainment hits on the home screens along with Davy Crockett and Lassie.

The TV ad has raked in as many fan letters as live performers get. George Gobel hollered the punch line on his TV show. Milton Berle, also with a different sponsor, got a laugh with the line on his recent fall debut. Newspapers used the line in cartoons when the Ford wage strike was settled and when Whitey Ford of the New York Yankees starred on the mound.

There were at least five spots in the It’s a Ford series. In each, the centerpiece is the mouth. Hubley’s collaborator, Bob Guidi, masterminded this visual gag in mid-1954. “I got the idea of having the character spell out the brand name with his mouth, to stretch the word,” he said. Whenever someone says the line, their mouth transforms into the letters.

By late ‘55, Hubley’s most famous piece for Ford was reportedly one called Ford “Bird” — a 20-second spot you’ll find below. It aired sometime between late ‘54 and early ‘55. Stan Walsh handled the animation, imbuing the simple bird character with infectious energy. Known for Bop Corn, Walsh was one of Hubley’s most versatile and innovative commercial animators, but he’s rarely gotten his due:

4. Last word

That’s all for this week! Thanks for sticking around. We’ll be back next Sunday with more animation highlights from around the globe.

One last thing. If you’re reading by email, you’ll notice a slight update to our animated outro banner below. Enjoy! For readers who aren’t signed up — the banner only appears in our emails. Catch it next week by joining our mailing list:

Hope to see you again soon!

From Starting Point: 1979–1996, a collection of writings by and about Miyazaki — which we quote throughout the article. Certain quotes and bits of information also come from Turning Point: 1997–2008.

These quotes, and much of the other information about The Snow Queen, come from the book Классик по имени Лёля в стране мультипликации (2010).

Thanks for this long article on "The Snow Queen"! I hadn't been aware of its heavy influence on Miyazaki. I finally added the film to Animatsiya.net, so it's now possible to watch it online with subtitles in 8 languages, and included a mention of this article: https://www.animatsiya.net/film.php?filmid=658

The first video is an AI-assisted HD version of it currently on Youtube that looks quite nice to my eyes (or as nice as we'll get until there is a proper HD release, which there surprisingly hasn't been yet).

This is one of those films that I (somewhat oddly) haven't paid as much attention to *because* it is so universally famous.

By the way, there is an earlier excellent 1946 Soyuzmultfilm animation, "The Song of Joy", that also features a young girl getting kidnapped by the queen of cold: https://www.animatsiya.net/film.php?filmid=657 (although other elements of the story differ). Many of the Soviet cartoons of that immediately post-war era feel so cozy...

Thanks so much for the link to watch Snow Queen! That clip of the old woman pulling Gerda's boat put me in mind of Spirited Away.