Welcome back! We’re here with another Sunday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and the plan goes like this:

1️⃣ On Chicken Run’s very British style.

2️⃣ Animation news worldwide.

For those just joining us — it’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues. Get them in your email inbox, weekly:

Now, we’re off!

1: That Aardman style

When Aardman drops a new project, it’s always worth paying attention. The team has a track record most can only envy. Despite all the Oscars, all the money and all the Wallace and Gromit sequels, the studio has kept its idiosyncrasy. No matter how big Aardman gets, it stays Aardman.

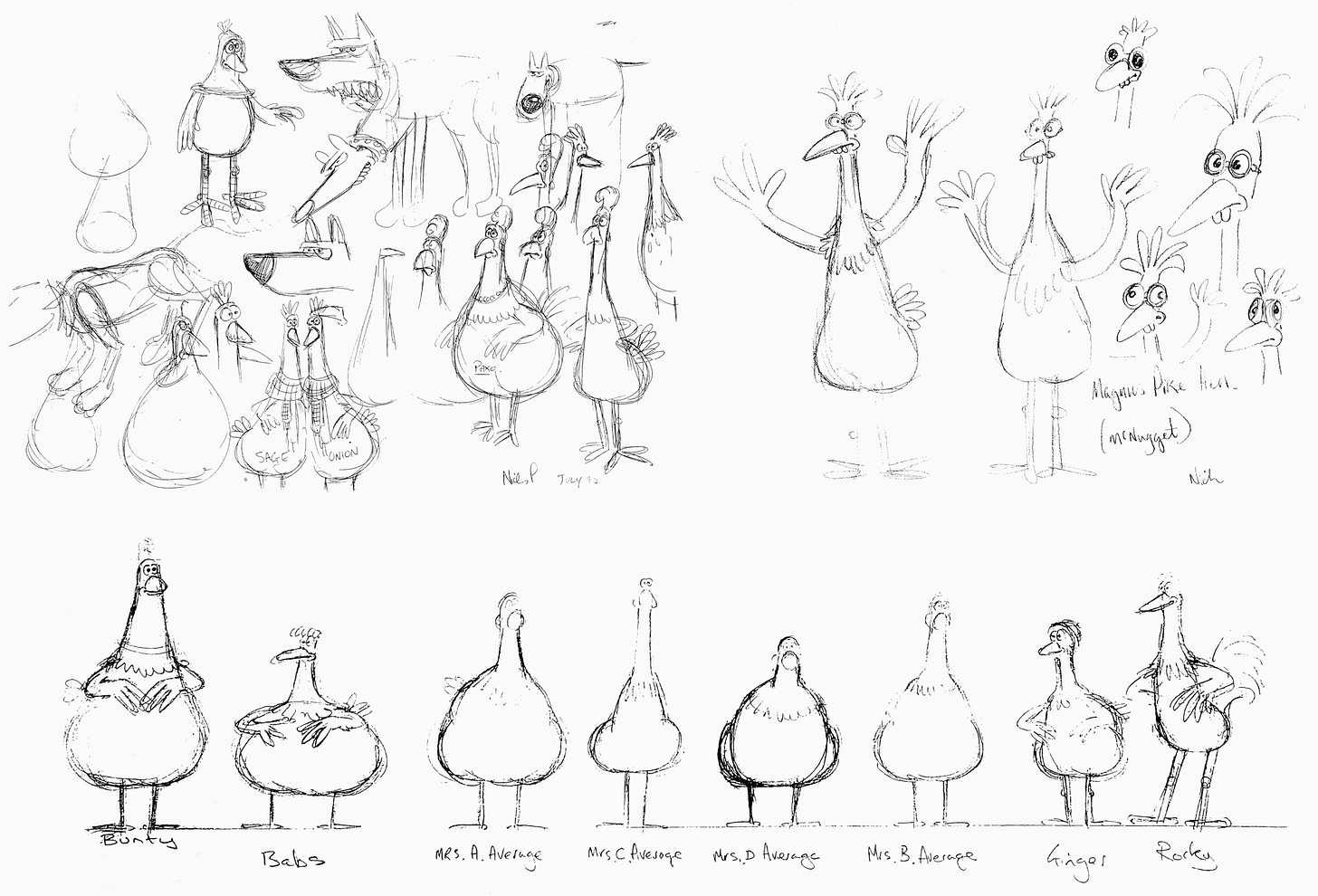

Which, if you think about it, can’t be easy. The first Wallace and Gromit film, directed and (almost entirely) animated by Nick Park, came out in 1989 and set the tone for the studio’s work from then on. But it was a weird, one-off passion project created across six years — how do you recapture that?

This question occupied Aardman as the company grew throughout the ‘90s. To date, maybe nothing has posed as much of a threat to its identity as Chicken Run (2000), its first feature-length project. The film is a classic today — the highest-earning stop-motion feature ever. A sequel is due out later this year.

Back then, though, there was real concern that Chicken Run would kill the Aardman spirit.

To make this film, the small Bristol studio ballooned to over 150 members. Nick Park, once a solo filmmaker, was now a co-director who no longer had time to animate. Aardman couldn’t fund it alone, either, and went to Hollywood for backing — partnering with DreamWorks. “[P]eople who loved Wallace and Gromit were a bit worried,” Park explained. “They thought that a big studio might ruin or limit our quirky style. We tried very hard to retain our own voice.”1

Creating a stop-motion feature is brutal in itself. Yet the team had another, equally challenging goal: “it was important to us to keep that Aardman style,” Park said.

Making industrial-scale films that felt like Aardman was already a problem by the mid-1990s. The first serious case was A Close Shave (1995), the third Wallace and Gromit short. A Grand Day Out (1989) had been an Oscar nominee; The Wrong Trousers (1993), an Oscar winner. Each entry in the series was bigger and more ambitious than the last. By A Close Shave, Park had become more of a director than an animator.

He had to delegate to a team now. Here’s David Sproxton, co-founder of Aardman:

… it’s a bit like taking over a role from a well-known actor on a soap. Nick would organize master classes with the animators, and say, “This is how Wallace behaves, this is how Gromit behaves, these are his key movements, these are his key gestures.” And he’d try to get the animators to fit into a mold.

Park wanted to transmit a personal style he’d invented with his own hands. “I suddenly had to coach all these animators. I had to tell them when their work was a little wooden. I had to push them in the direction I wanted to go,” he recalled. Park was after something extremely specific, and worked hard with the animators to get it.

Sometimes, this demanded new solutions — like creating a range of pre-made mouths to swap onto the characters when they spoke. These became part of Aardman’s new pipeline. With so many animators, doing mouth movements by hand led to flaws.

A Close Shave eventually won the Oscar and went down as another Wallace and Gromit gem, but Park’s concerns didn’t go away. “[S]omething happens when there’s a lot of people,” he said. “Things get naturally slicker and the animation gets smoother and the finish gets even smoother. … The animation in some ways got a little more conservative as well.”

This fear of betraying Aardman’s quirkiness, its house style, guided the studio as it explored ideas for a feature in the mid-1990s. Aardman had clout in Hollywood — it kept winning Oscars, and people in the business loved Wallace and Gromit (and Creature Comforts). It wasn’t hard to find project offers. In fact, there were dozens.

“The trouble was, most of the suggestions were simply not us at all,” recalled Sproxton. There were endless fairy tale pitches, and even one to animate Tank Girl. Accepting one of them would’ve put the studio’s identity in jeopardy.

So, Aardman offered Hollywood its own idea. Famously, Nick Park’s sketch of a chicken digging its way under a fence turned into the Chicken Run concept: “The Great Escape. With chickens.” One successful pitch to Jeffrey Katzenberg and Steven Spielberg later, and the team was in business with DreamWorks. Chicken Run was announced in 1997, with Park and Aardman’s Peter Lord as co-directors.

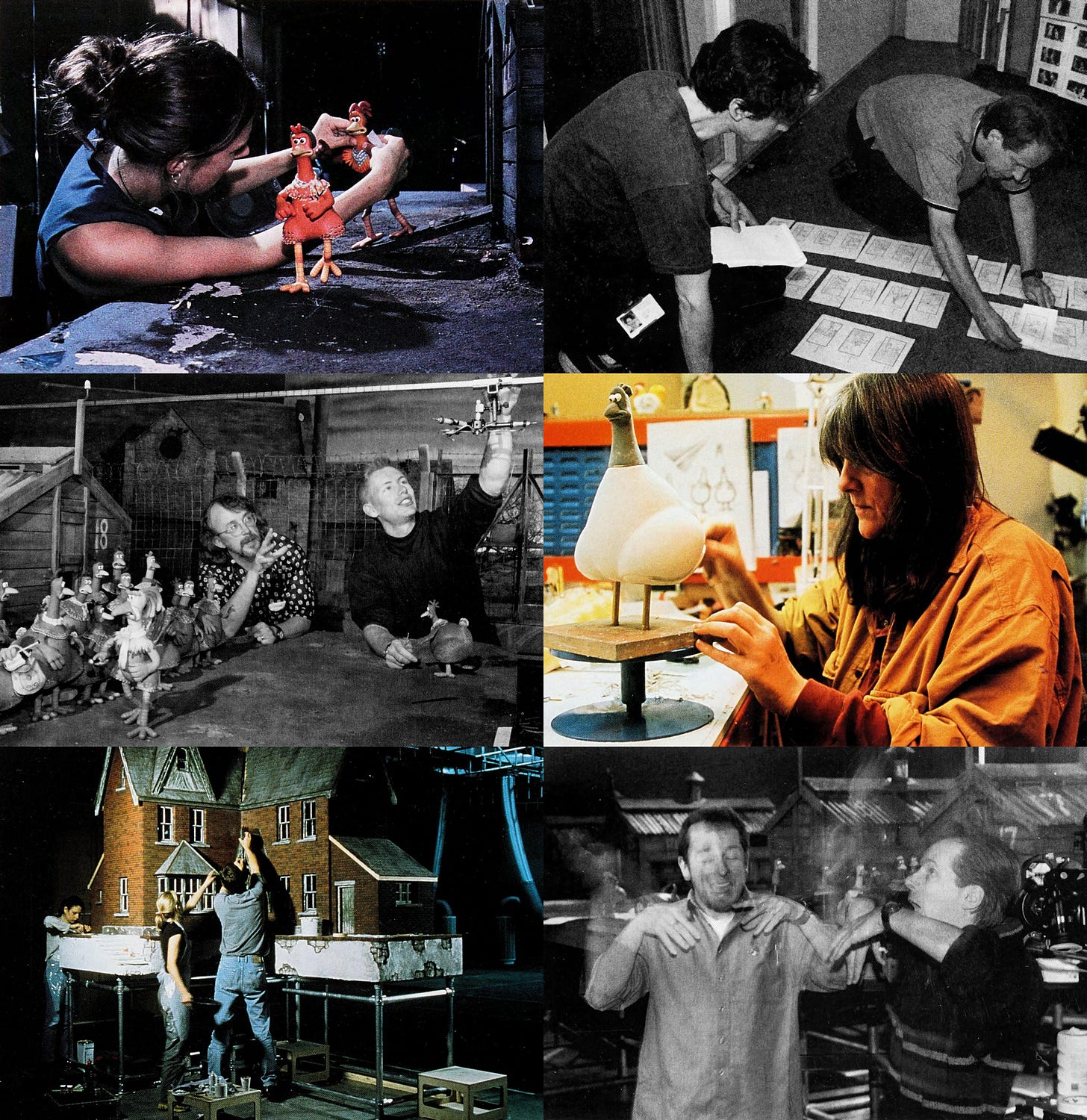

Everyone knew that a feature would put a huge strain on the studio — it was already staffing up by 1996. The team “ran two six-month training courses in association with the University of Western England” to bring in fresh, Aardman-ready animators, according to author Brian Sibley.

By 1998, Aardman was prepping a second studio in Bristol, converting an industrial shed (at least 55,000 square feet) into a new workshop.2 The entire building would be in use by the end of Chicken Run, to the point that another space was needed. By itself, the act of moving studios and splitting up the team risked fracturing the Aardman process, but there was no choice. Chicken Run was too big to do otherwise.

And then there was the script. “Peter and I decided we needed a writer, someone who knew about feature film structure. But we also wanted to maintain that quirky British humor,” Park said. The first screenwriter they hired, a Brit, gave them something way off from the Aardman vibe. They let him go. The second, an American named Karey Kirkpatrick, took a different approach. According to Peter Lord:

What he did was enter into the project with a sensitive — almost withdrawn — attitude. He said: “It’s your film, I’m just here to realize it.” If he had come along, appearing to be the auteur, telling us what to do, I doubt if we’d have succeeded in working together. He was very clever in leaving any criticisms until we were comfortable with one another. It was only then that he started to say things like, “I love these ideas, guys, but they really don’t fit! You can’t do it because you’ll never get it all in the film.” By that time, of course, we were ready to listen.

Kirkpatrick proved to be what they needed — someone who knew the feature film process (which Lord and Park didn’t), but was willing to veer Aardman’s way over Hollywood’s. He added the central romance to Chicken Run, but said that the directors pushed him back from sentimentality: “they beat that out of me.”

“So there was a constant, lively and key debate between the three of us throughout this process: ‘Was this scene too cheesy?’ ‘Was that line too obvious? Too... American?’ ” Lord remembered.

There were fights with Katzenberg, one of the most Hollywood of Hollywood producers, over the sheer Britishness of the project. Park said, “[W]e wanted Chicken Run to feel as British as we possibly could — and of course Jeffrey wanted to make sure it could be understood by American audiences.” One dispute, according to the team, arose over the presence of the local insult wazzock in the script.

Asked whether Aardman had “insisted” on creative freedom with Chicken Run, Park put it plainly. “It was a good relationship from the start, but we definitely insisted,” he said. “Don’t misunderstand me. The studio also had their prerogatives, which they pushed.” This wasn’t all bad, by any means. Park praised the DreamWorks composers and storyboarders for taking the film to the next level. But it was a balance.3

Aardman’s core team went into the feature film process, and the Hollywood process, with an understanding of its own identity. From there, it was a matter of defending it — and communicating it to the studio’s many, many new members (its size during Chicken Run peaked around 200 people). With so much changing, the Aardman idiosyncrasy was at constant risk of being watered down.

Throughout the pre-production phase, and the 18 months of full production, Park and Lord had to reaffirm the vision again and again and again. As Lord said of the period, “What does a director do? He answers a question every five seconds — all day, every day.” The directors divided things between themselves, each supervising a team of seven “key” animators who oversaw animation teams of their own. Park and Lord acted out many of the scenes, and countless reference videos were shot.

Like most stop-motion features, Chicken Run was done by creating exact duplicates of each character so that multiple animators could work on the film simultaneously. It was too slow otherwise — by 1999, the most animation that Aardman had shot for Chicken Run in a single day was 26 seconds. Animators were partitioned off in the industrial shed; the directors darted between units. As Lord said:

You really have to keep your wits about you. You’re talking to an animator about one scene and then someone suddenly says, “Quick! Off to Unit 23!” and you think to yourself, “What the hell’s Unit 23?” And it’s not until you go through the curtain to Unit 23 that you remember what’s going on there, by which time you are being expected to talk intelligently about it.

The task of overseeing Chicken Run was so big, in the end, that the directors weren’t sure if they’d kept the film true enough to Aardman. Even years later, Park still felt like it had drifted.

As he said:

I knew my characters and sense of humor very well, but the studio process was entirely new. I couldn’t write the story myself, or do the storyboard all by myself. Other people were involved now. And there were so many scenes. […] Chicken Run wasn’t exactly in the Aardman style. Since childhood I’ve always wanted to put my own mark, my own style, on something. And I found it with Wallace and Gromit, with that extremely large mouth and his simple syllables. It reflected a northern English way of speaking. I think we got lost a little bit on Chicken Run. We had never made anything for the big screen before. There was confusion on our part.

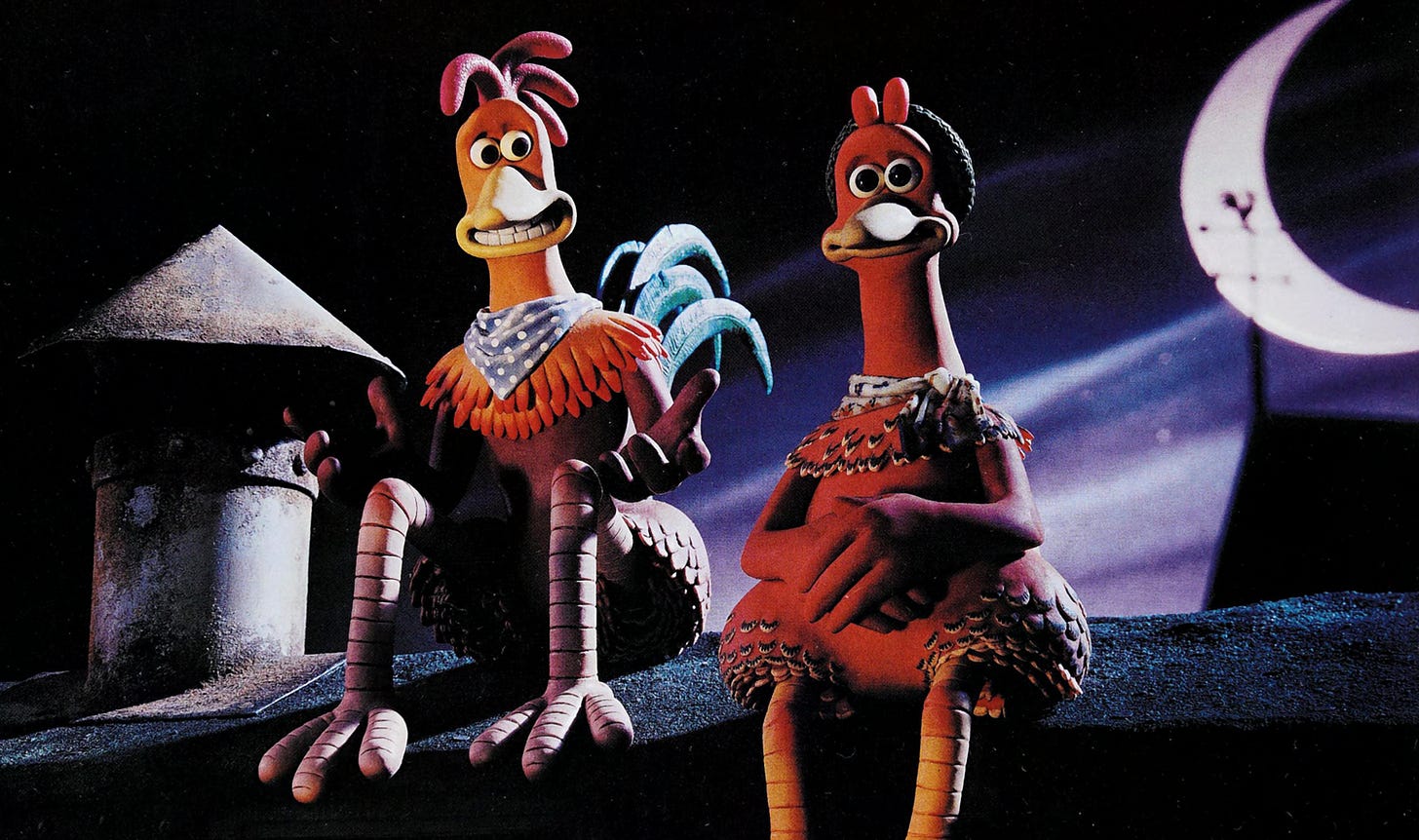

Trade-offs were certainly made. To create chicken characters who looked like Park’s drawings, for example, the team couldn’t use Aardman’s standard material (Plasticine) for most of their bodies. It was too unwieldy. The final chickens had Plasticine arms and heads, but the bulk of each character was steel and molded silicone. Tricks and shortcuts like these were spread all throughout the film.

Even so, it’s hard to agree with Park that Chicken Run lost Aardman’s style. It really does look and feel like the studio’s work. For many, it’s become the quintessential Aardman film — including in Britain. The Guardian named it the studio’s best ever in 2019.

Yet it makes sense that Park had the takeaway he had. It was probably inevitable — maybe even necessary. In a real sense, it was this fear of the studio losing its voice that kept Aardman Aardman. The team had to be hypervigilant, which can make small changes feel like major defeats. For everyone else, watching from the outside, Chicken Run just looks right. A true Aardman classic — only bigger than before.

2: Newsbits

The Ukrainian film Unnecessary Things, which we’ve praised, screened at a major Kyiv theater. There, its director played a teaser for his next project: a feature called The Last Cossack (watch), with a similar sci-fi flair to Unnecessary Things. Funding is uncertain, he says, as “the state currently has other priorities.”

In China, Feinaki Animation Week brings the “Feinaki Inspiration Picnic” to Xi’an later this month, featuring Chinese and foreign animation from recent years.

The animated YouTube series Great Russian Villains, produced by Russian dissidents Mikhail Zygar (journalist) and Ilya Khrzhanovsky (director), retells the stories of past Russian leaders with an eye toward the present. Standouts include Ivan the Third and the zombified claymation Lenin. All have English subtitles.

In America, the Eisners nominated Alex Dudok de Wit’s translation of Shuna’s Journey (by Hayao Miyazaki) for an award.

See a clip of the Spanish film Robot Dreams, which just premiered at Cannes. Adapted from an American graphic novel, it’s about a dog and a robot in ‘80s New York. Neon (Parasite) will distribute it in the United States.

Meanwhile, Spain’s They Shot the Piano Player was picked up by Sony Pictures Classics for a North American release. It comes from the directors of Chico & Rita.

As of this week, all 13 episodes of the Czech classic Mach and Šebestová are finally available in English, thanks to historian and translator Toadette. Find the playlist on YouTube.

A new advocacy group has just emerged in Japan: the Nippon Anime & Film Culture Association (NAFCA). In a statement, NAFCA wrote that anime production is “on the verge of collapse,” and that it seeks better conditions and communication in the industry.

Important animation funding stories in England and Belgium: the BFI is handing out $2.6 million to local studios, and Wallimage backed four animated projects (including a series with the fun title Billy the Hamster Cowboy).

Lastly, we wrote about the essential Soviet film The Cow (1989) by Alexander Petrov, paint-on-glass animator.

Until next time!

From Nick Park’s interview in On Animation: The Director's Perspective (Volume 1), which we’ve cited many times. Most of the rest of the write-up is sourced from the books The World of Wallace & Gromit, Chicken Run: Hatching the Movie and A Grand Success: The Aardman Journey, One Frame at a Time. One other reference was this interview.

The shed is described in A Grand Success as being 80,000 square feet, but a news report at the time in the Evening Post (March 7, 1998) put it at 55,000. The latter figure was mentioned in many other outlets, too. It’s hard to guess how the discrepancy arose, or which number is accurate, but it’s safe to say that the shed was “at least 55,000 square feet.”

It should be said that Katzenberg, despite his reputation, was far from just an annoyance on Chicken Run. As recounted in A Grand Success, he took a huge risk here, backing it with a full press-and-advertising push even when data suggested that the film would fail. The gamble paid off, setting Aardman on the course it’s on today — but it was Katzenberg who made that difficult call. Park, Lord and Sproxton all had positive things to say about him.

Love Aardman. And Chicken Run was great. W&G are still my faves, but Chicken Run was loads of fun and looked right. And they kept it weird.

omg this post was so great! I loved Chicken Run as a kid in 2012-- one of my school teachers did a Great Escape/Chicken Run double feature for my middle school British culture elective class (it was not a normal school lol). Each film is a landmark piece of cinema in their own right but I had no idea about the additional production process of Chicken! So this was super insightful!!!