How Do You Define Anime?

Plus: animation news worldwide, Hayao Miyazaki on Fleischer.

Welcome! We’re back with another issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s the plan for today:

1 — what does the word “anime” really mean?

2 — animation news around the world.

3 — the week’s loose ends.

4 — what Hayao Miyazaki thinks of Fleischer cartoons.

We publish every Sunday and Thursday. If you haven’t already, you can sign up for our Sunday issues for free — they’ll land in your inbox each week:

With that said, let’s dive in!

1. What is anime, anyway?

This month, we’ve written a lot about Japanese animation — today’s issue is our fifth in a row about it. We’d like to round out this informal series with a quick question. Namely, when the world talks about anime, what does it mean? And does it mean what you think it means?

At this point, anime’s known pretty much everywhere. The BBC recently wrote another article, the latest in a long tradition, about how anime has “taken the West by storm.” Last year, a special conference at Annecy highlighted the enormous impact of anime on animation luminaries in Europe and beyond. But how do you define this thing that we all recognize?

It’s often said that anime is just a Japanese word for “animation.” That’s kind of true. To many people in Japan, Spirited Away would be Japanese anime, Frozen would be American anime and Wolfwalkers would be Irish anime. But that’s not a universally accepted definition in Japan.

Consider what the founder of Japan’s Studio Ponoc (Mary and the Witch’s Flower) said a few years ago:

We see ourselves as creators of “animated films”… “Anime” is more of a genre. When the term “anime” first appeared outside Japan, most of the films associated with it were sexual or violent. We would like to avoid misunderstanding. We want our films to be seen by a wider audience.

Many wouldn’t agree with calling anime a genre. In his seminal book Anime: A History, historian Jonathan Clements writes that “anime is not a ‘genre.’ It is a medium.” We agree with him. He uses the word anime, more or less, as a catch-all name for Japanese animation. In general, we do the same.

But Studio Ponoc’s take doesn’t come from nowhere. In Japan, the word anime has always had a loaded meaning for some people. One of them is Hayao Miyazaki, a fierce and cantankerous critic of anime.

A long time ago, back in the ‘50s and ‘60s, the term manga eiga (“cartoon film”) was commonly used to refer to animation in Japan. Although the word anime came into wide use by the ‘80s, Miyazaki kept calling his work manga eiga. He saw anime as a distinct entity. As he wrote in 1987:

I frankly despise the truncated word “anime” because to me it only symbolizes the current desolation of our industry. […] I have never had any interest in being one who defends, represents or even analyzes Japan’s anime culture.1

For the Miyazaki of 1987, anime was a subtype of animation defined by “overexpressionism.” He wrote of projects where “vaporous and extremely deformed characters [inhabit] distorted and flashily colorized worlds, and where time [is] infinitely expanded.”

A decade later, Miyazaki was still saying the same thing. He told a Japanese newspaper, “We have consistently tried to make ‘films,’ not ‘anime.’ That is, to express time and space with more universality.”2 He argued that anime was nothing more than a series of stylistic cliches, understood by “the creators and the fans,” that made no logical sense to anyone on the outside.

The irony is that Miyazaki’s work was, itself, a central part of “anime culture” in 1980s Japan. His film Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was a touchstone for the same Japanese fans who used the word anime rather than the older, less cool manga (cartoon).

In 2015, the writer Carl Gustav Horn explained as much in a great essay. Along the way, he noted that Otaku no Video, a 1991 anime film about the otaku lifestyle, contains a scene that:

… recalls waiting in line for the debut of Miyazaki’s Nausicaä in 1984, and how the way young fans insisted it be called anime instead of manga sounded affected to regular people.3

The scene takes place around the 42:30 mark. In it, a character loudly protests against an older man who refers to Nausicaä as manga, or a cartoon. “It’s not a cartoon!” the fan shouts in response. “It’s anime!”

Nobuyuki Tsugata, the Japanese animation historian, has pinpointed Nausicaä as a key work in the development of “anime,” which he also sees as a separate stream of animation. As Clements relates in Anime: A History, Tsugata’s argument is that anime is defined by “foreign interest, transgression, visual cues, merchandising” and more.

All of which is to say that the word anime is a bit more complicated than it appears at first glance. There’s a lot packed into it. Sometimes, it can feel like no two sources agree on how to define it.

We’ll keep using the word to mean “Japanese animation,” but there’s a real debate to be had about what anime is, what it means, where it’s been — and where it’s going.

2. Global animation news

Sunao Katabuchi’s next film appears

Speaking of where anime is going, director Sunao Katabuchi revealed his next feature this week. (We covered the incredible story of his debut film just recently.)

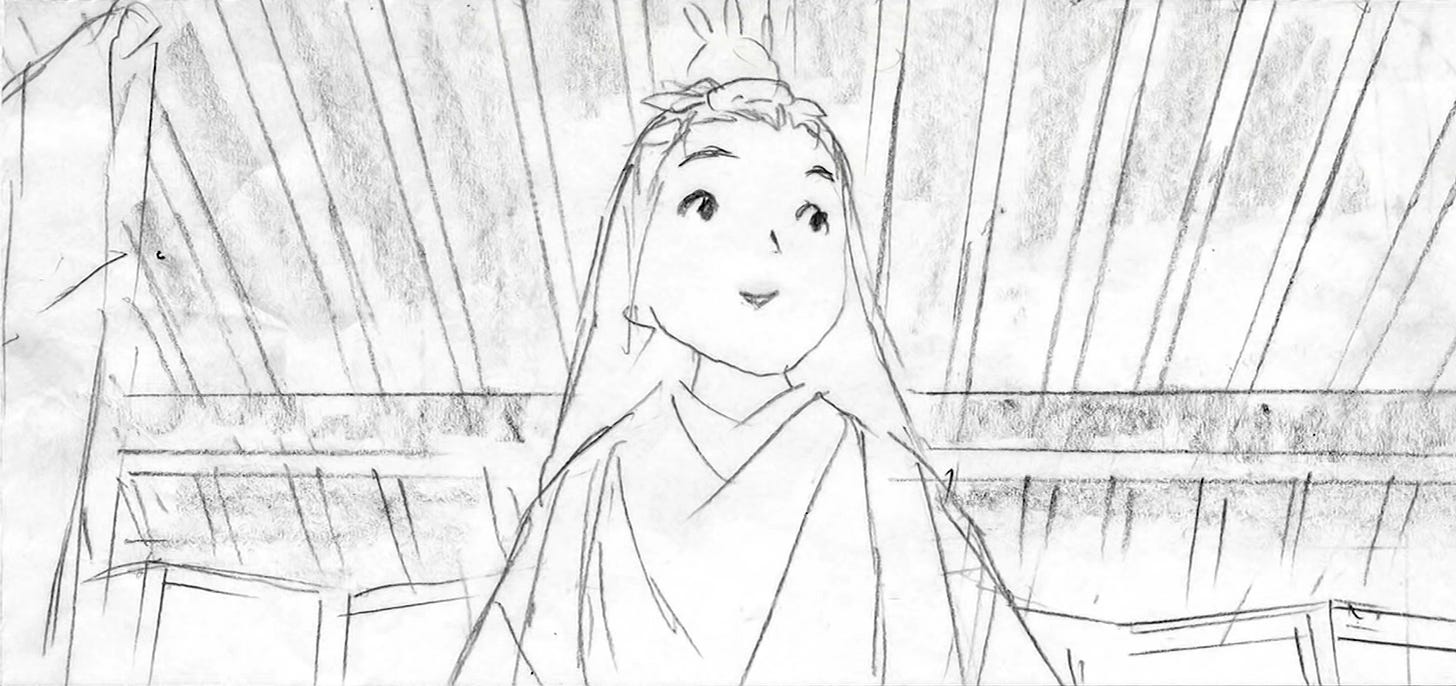

Katabuchi and his studio Contrail showed off the project, which is currently nameless, through a teaser video that contains storyboards and behind-the-scenes footage. He’s been developing the film since 2017, and it’s now in production. Like all of Katabuchi’s features to date, this is a period piece — this time set in 10th century Japan.

In a statement, Katabuchi explained that he’s circling back to subject matter from his earlier feature Mai Mai Miracle (2009). The real-world court lady Sei Shōnagon, who wrote Japan’s Pillow Book, occasionally appears in that film and will star in his new one (with largely the same character design).

Alongside the reveal, the National Institute of Japanese Literature tweeted a thread that showed Katabuchi in its archives, studying ancient paintings. Obviously, though, Katabuchi isn’t the only one on this project. Chie Uratani, his wife and a veteran animator from projects like Kiki’s Delivery Service and Magnetic Rose, is the assistant director. The chief animation director is Masashi Ando, one of Japan’s top animators.

We’ll keep an eye on this project as it proceeds.

Animation in Ukraine and Russia, continued

Since Russia began its invasion of Ukraine, we’ve been covering the state of animation in both countries in as much detail as we can. The reason is twofold. First, we feel it’s important not to act like this war isn’t happening — it very much is. Second, war is damaging animation in both countries in ways rarely seen before.

This week, Kidscreen did the world a service with a top-tier article on Ukrainian animation. Writer Ryan Tuchow contacted a number of figures in the field. “Prior to the invasion, there was a general sense that Ukraine’s animation industry was on the rise,” Tuchow writes. Not anymore.

The industry’s very existence is in peril — especially because it’s lost the Russian market, one of the biggest importers of Ukrainian cartoons. One professional says:

Ukrainian companies will no longer work with Russian companies after this […] Our country will be totally different, and it will take a little time for Ukraine to get over this economic crisis because half of our country is totally destroyed.

Meanwhile, Russia’s entire film industry is sinking fast. Desperation is leading to wild moves. Almost a third of Russian theaters have frozen ticket prices to pre-crisis levels, despite the collapse of the ruble since then — a costly bid to increase viewership. And the makers of Moonzy & Moona, a major Russian cartoon series, just sold all of its IP rights “in the western hemisphere” to foreign producers.

The economic blockade is hitting Russia’s ability to animate at all, as it loses business with foreign developers of animation software. Companies are casting about for domestic alternatives, and for co-production deals with whoever will have them. China and Latin America are major targets.

This week, Russia’s various “creative industries” got together to discuss survival in this climate. One big takeaway: more state financing. And Russia is already on it, passing a law to allow the government to fund 100% of an animated production, with caveats related to how recently the director graduated and where they studied.

“Animation today is in a very difficult position, like the whole of Russian culture,” said Yuliana Slashcheva, the head of Soyuzmultfilm, in an interview this week. She discussed Russia’s eviction from the global market, and how boycotts threaten to destroy “everything” that Soyuzmultfilm has built internationally.

“We are not politicians. We are artists and educators; our tools are images and words,” Slashcheva said. Coming from her, that’s a tough sell. Slashcheva and her studio have forged close ties with the Kremlin, and, lately, have begun to inject Russian nationalism into the work itself. Their upcoming Alpine Campaign, about a Russian war hero, is backed by the Ministry of Defense. The MoD orchestra is scoring the film.

Yet support for the war among animators remains far from universal, to say the least.

In a recent interview with the embattled independent paper Novaya Gazeta, animator Anton Dyakov talked around the issue but made his unhappiness known. Dyakov spoke carefully about how his grandfather, a World War II vet, had known war only as pain — and how politicians still don’t realize that war has no winners.

While Dyakov’s amazing cartoon BoxBallet was nominated for an Oscar, the invasion prevented him from obtaining a visa to travel to America. At the same time, he told the state-owned media outlet TASS that it was difficult for him “to whine about not being allowed to go to the Oscars when so many people are in extreme conditions.”

Best of the rest

On the subject of the Oscars, The Windshield Wiper just won Best Animated Short and Encanto picked up Best Animated Feature. The excellent Flee, up in three categories, was shut out — an embarrassing misstep by the Academy.

Maybe the biggest American story of the week was the Disney walkout, a protest against anti-gay legislation in Florida. You’ve likely read about it already — if not, the Los Angeles Times has you covered.

Looking to watch the French documentary Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist? It’s streaming for free right now via Eventive. Slots are limited, so don’t wait.

In Japan, a fun new section of the upcoming Ghibli Park, the Elevator Tower, is complete and being shown off in exciting photos.

A bunch more classic cartoons by American legends Faith and John Hubley are available, in newly restored quality, via Criterion Channel.

Meanwhile, a Japanese classic is getting a restored release in America via GKIDS — Isao Takahata’s Panda! Go Panda!

Indian animation “grew by 24 percent” in 2021, yet problems persist. Mumbai’s Popcorn Animation Studio describes partners who offer low budgets but demand “higher production values,” even as remote work slows the pipeline (“rural animators are grappling with poor internet and power connectivity”).

America’s own Jeron Braxton is one of the furthest-out animators working today. He’s released a film through Adult Swim, Baby Demon — a brain-melting fever dream from last year that’s only coming onto our radar now.

Also in America, the New York studio Hornet has opened its summer internship program. April 3 is the application deadline. “One of the few studio internships in NY that’s paid,” tweeted animator Ally Gonzalez. “Go apply.”

Lastly, we explored the Japanese film Invisible — a modern classic by a Ghibli ace.

3. Loose ends

Thanks for reading so far! We hope you’re enjoying today’s issue.

We were thrilled by the performance of last Sunday’s newsletter, The Real History of Perfect Blue and Requiem for a Dream. It was a success beyond anything we could have imagined — thank you. Welcome to all of our new readers.

The issue broke our one-day traffic record, and then nearly did it again. On Twitter, it was by far our most popular issue ever, surpassing even our Cartoon Modern scanning project from October. It reached #4 on Hacker News, where it generated quite a bit of discussion. We were also very happy with the attention it received on Reddit.

And there were so many amazing comments. The always-kind Nick Francis, creative director of Picture of a Fish, called us an “unstoppable force.” We saw praise from Lynzee Loveridge (executive editor of Anime News Network) and film writer Farran Nehme. Artist Rachel Merrill remarked:

Heartbreaking to read from @ani_obsessive. It’s an understatement to say how important Kon was to so many of us just beginning to learn what film can do.

Throughout the week, the issue generated hundreds and hundreds of comments like these across the internet. We wish it was possible to highlight them all, but there’s just no space. We’ll mention two more that particularly stuck out to us.

“I love this newsletter and this week’s — about one of my favorite-ever directors — is a strong reminder of why,” replied writer Kambole Campbell, who’s published with outlets like Sight & Sound and The Guardian. “Passionate, fascinating and even-handed in how it breaks down decades of clashing accounts.”

Lastly, Jason DeMarco (co-creator of Toonami and SVP of anime production at Warner) tweeted:

Great piece and the first one to acknowledge what I’ve heard from people in the anime industry who worked with Kon: he could be a vicious collaborator.

We deeply appreciate these replies and so many more. The story of Perfect Blue and Requiem for a Dream is messy, and emotions around it run high. It was really amazing to see so many readers follow it through and wrestle with its complexities.

The rest of today’s issue is for our paying subscribers (members). Below, we explore Hayao Miyazaki’s thoughts on Fleischer. Believe it or not, he has strong feelings on the subject, and an unexpected love for Popeye.

Members, read on. Everyone else — we’ll see you next week!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.