How Roy Morita Shaped 'Rocky and Bullwinkle' and Beyond

Plus: global animation news and an unusual Yugoslav cartoon.

We’re back! Another Sunday, another issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. And here’s the slate for today:

One — the importance of animation artist Roy Morita.

Two — animation news from all around the world.

Three — a quick look back at Opening Night.

Four — the last word.

We publish every Thursday and Sunday. If you’re new here, you can sign up for free to receive our Sunday issues in your inbox every weekend. It’s quick and easy:

With that said, let’s get going!

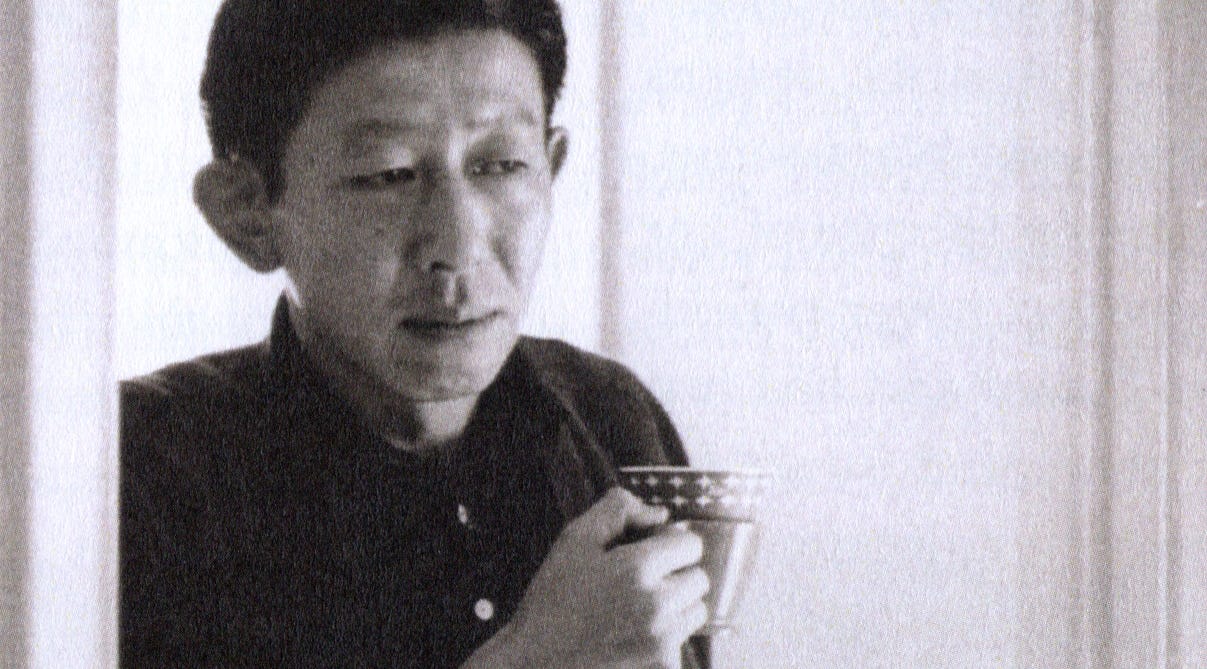

1. Roy Morita, the natural

Not many TV cartoons are as revered as The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends. After it first aired in 1959, it spent decades as the cartoon high-water mark for many. It was still influencing shows like The Powerpuff Girls in the 1990s.

A talented team at Jay Ward Productions made Rocky and Bullwinkle happen. Plenty of artists’ hands touched the series — and its iconic writing wouldn’t be there without Bill Scott, also known for his work at UPA. But one artist played something of an outsize role in defining the look of the show and Jay Ward’s cartoons as a whole. That was Roy Morita.

In his seminal book The Moose That Roared, historian Keith Scott wrote this:

The importance of the late Roy C. Morita’s role in the Jay Ward cartoons cannot be overstated. He was the first artist to design and work on the characters and was responsible at the beginning for more of the overall visual direction than any other artist in the Ward Productions story.

Historian Darrell Van Citters painted a similar picture in The Art of Jay Ward Productions, calling Morita “integral to practically every project that moved through the studio.” Morita even drew the pilot for Rocky and Bullwinkle, working alongside painter Sam Clayberger. (Later, Clayberger himself said that Morita was “very responsible for the Jay Ward look.”)

At Jay Ward, Morita wore multiple hats. He designed characters and drew layouts — and storyboarded a lot. He and his fellow artist Shirley Silvey, another huge force at the studio, reportedly storyboarded most of the Rocky and Bullwinkle segments that actually star Rocky and Bullwinkle.

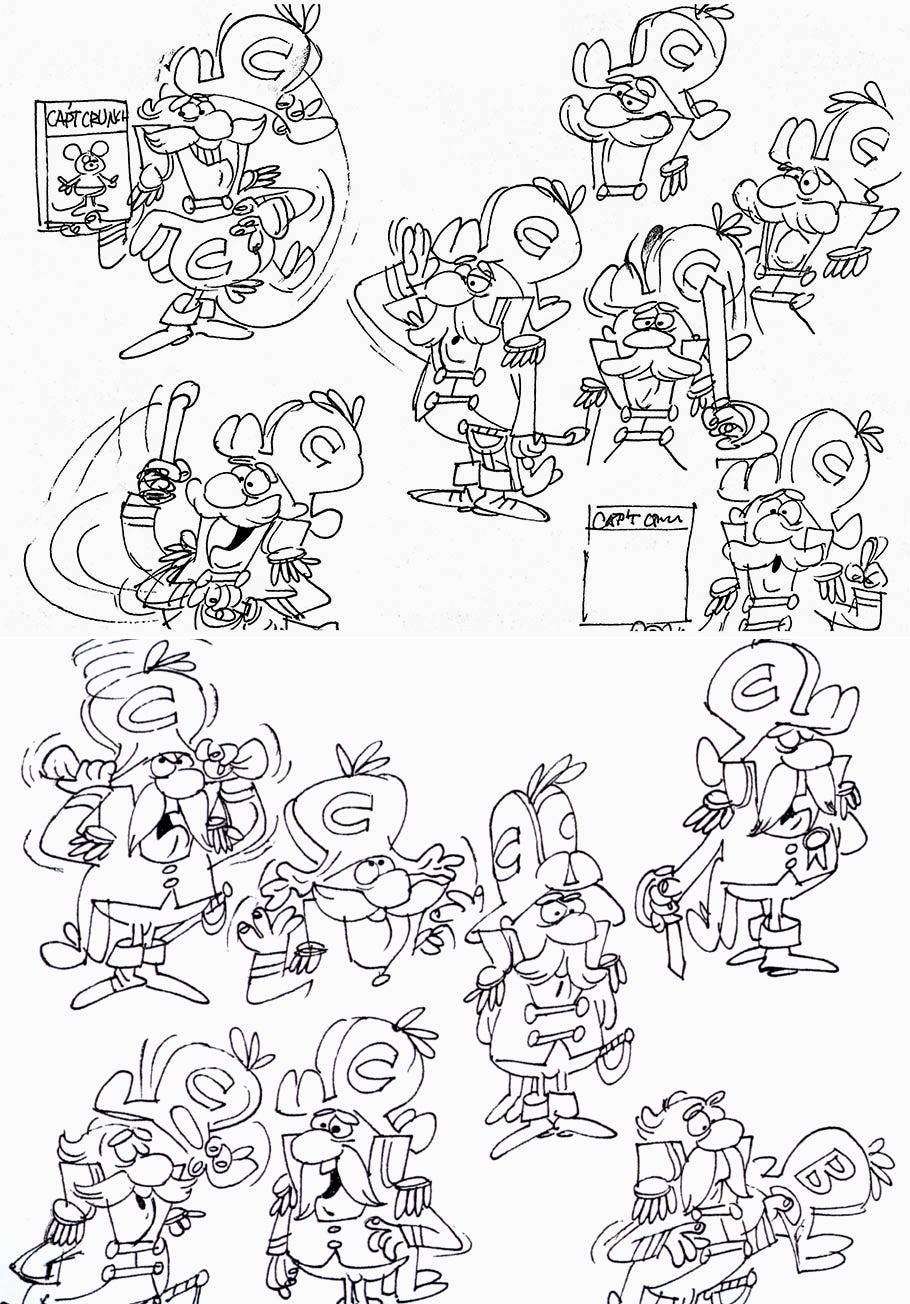

“Morita had the reputation of being the fastest board artist at Ward,” Van Citters wrote, “and although his drawings were loose, they were also filled with personality.”

Or, as artist David Weidman recalled, “Roy Morita … was perfect for the business, I think, because he was a natural. It just came out of him.”

Born in California during 1928, Roy Morita had first risen to prominence at UPA. He was one of several key Japanese-American artists at the studio in the 1950s. Designers like Chris Ishii and Jimmy T. Murakami had been interned during World War II, but moved up to major jobs at UPA. (Historian Adam Abraham called these opportunities “typical of UPA’s progressivism.”)

Morita designed for UPA’s commercials, and for The Boing-Boing Show (1956–1958), the wildest project in the studio’s history. It was a TV playground for UPA’s new wave — art-school graduates (Morita attended Chouinard) with a hunger to try new things. Van Citters again:

Many of these artists brought a new sensibility and excitement to animation, one unencumbered with the formulas and traditions of the past. Their new frontier was television.

A number of people from The Boing-Boing Show wound up at Jay Ward Productions, including Shirley Silvey. Morita just got there sooner than most. He was still at UPA when he had the chance to freelance on the pilot to Rocky and Bullwinkle.

“We had stuff scattered all over floors and tables,” said Clayberger, recalling the pilot’s production in a small office space they used to work. “It was a frantic undertaking, but enjoyable.”

Once Jay Ward got the series picked up, a year later, both Clayberger and Morita found themselves on the ground floor of Rocky and Bullwinkle. The idiosyncrasies of Morita’s personal style became part of the show. As a designer and artist, Morita favored a freer, busier and more organic look than the UPA standard. He helped to move cartoon design forward, out of the ‘50s and into the ‘60s.

Morita spent a decade at Jay Ward Productions. During that time, he worked on everything from shows to promos to TV commercials, and even helped to design Captain Crunch.

Jay Ward and UPA weren’t Morita’s only jobs. As Van Citters pointed out, he was “a prolific artist and continually picked up freelance work.”

Among other things, he helped to design Dr. Seuss specials like Halloween Is Grinch Night (1977) at DePatie-Freleng. Before he passed away in 1984, Morita had even worked at Disney, doing whimsical art for The Black Cauldron — little of which reached the screen.

Beyond the research of Darrell Van Citters and Keith Scott, not much has been written about Roy Morita. He didn’t enter the limelight in his lifetime. Van Citters called him “a somber man of few words” and an artist of “quiet brilliance.” Although he was crucial (alongside artists like Al Shean and Shirley Silvey) to Rocky and Bullwinkle, Morita remains a hidden figure in animation.

“He was a kind of reserved, quiet personality, kind of a downbeat nature,” recalled director Bill Hurtz, who worked at Jay Ward Productions. “[But] Roy sure knew what he was doing.”

2. News around the world

Why is the UK cutting animation funding?

As we write week after week, animation for kids is booming. Live-action work aimed at young audiences is riding the same wave. So, it comes as a surprise that the United Kingdom has ended its Young Audiences Content Fund, which began in April 2019 as a way to support domestic production and local stories.

Among other animated projects, the program helped to give us Sol, a Celtic-language special about dealing with grief. It also supported preschool series like Milo and the upcoming Pop Paper City, in which Aardman is involved.

By all accounts, the program works. The UK government itself boasted about its success — in the same announcement that marked its end. Officials wrote that they “hope the Fund’s legacy will be to encourage UK broadcasters to continue to focus on programs that nurture and nourish and reflect the lives of young people in the UK.”

The decision has drawn blowback. One non-profit organization put it this way:

Now we face a definite decrease in the number and range of programs being made for young people in the UK. We could very quickly be back where we started three years ago, with the BBC as the only body commissioning content for children. And in fact, it’s worse, as the BBC is facing government-imposed budget cuts of its own over the next few years, too.

The closure doesn’t come out of nowhere. In the middle of last year, the UK government cut the fund’s budget from $80 million to $62 million. Back in October, there were rumblings that the program might die outright.

Animation in Europe runs on a network of grants, funds, tax shelter schemes and more. Just this week, an animation incubation program, backed by the EU, announced support for 12 new projects from around Europe. If kids’ programming specific to the UK is going to survive, it needs that kind of institutional backing.

The problem is bigger than just a loss of jobs for animators. In response to the threat of the program’s closure last year, Konnie Huq (Blue Peter) put it this way:

The flipside of being able to choose whatever you want to watch on YouTube is there’s no one particularly policing this content. As a society, we’re dumbing down on all fronts. […] We make sure kids are eating their broccoli and pay for all this good stuff to be put into their bodies and make them really healthy. But then it’s easy to shove them in front of a tablet as free babysitting.

Can the anime industry heal itself?

It’s no secret that anime is a victim of its own success.

Recent data suggests that Attack on Titan was “the most in-demand show” of 2021 across all genres and mediums. And, despite the economic wreckage of the COVID-19 pandemic, Toei raised its earnings forecast this week in response to huge revenue overseas (China is the top market).

Yet the industry’s pipeline has broken down. Look no further than the production of Tokyo Twenty Fourth Ward — the chief animation director recently live-tweeted the disaster as it unfolded. In the anime industry, budgets are too low, time is too short and, worst of all, there aren’t enough artists to go around. Demand is killing supply.

But what if there was a way to stop the bleeding? People are asking that question in Kōchi Prefecture.

Key forces in Kōchi Prefecture, including Kōchi Shinkin Bank, recently signed an agreement to boost anime in the region. They hope to address the industry’s labor shortage and grow the local economy. The recently-formed Studio Eight Colors is a core part of this plan, but there’s also an ambitious anime festival in the works.

The linchpin of this whole strategy is remote work. Most anime is produced in Tokyo, which is quite far from Kōchi Prefecture — but a remote work pipeline closes that gap. In the process, officials hope to encourage people to live outside major cities, to reverse the decline of Japan’s rural areas. During 2022, there are plans to set up “a satellite office base” in the city of Kōchi to support remote animation workers.

Even in Tokyo, companies are trying to navigate the labor crisis. One Japanese analyst argues that broadcasters like TBS Holdings are investing in in-house production because, with schedules so booked and so few animators available, it’s hard to commission a series unless you own a studio. For studios themselves, in-house production means more security — which can only be a good thing.

Best of the rest

Ghibli Park, Studio Ghibli’s upcoming theme park in Japan’s Aichi Prefecture, is scheduled to open on November 1.

The screenplay for another American animated blockbuster, Luca, is available to read courtesy of Deadline. (The artbook is free right now, too.)

The Summit of the Gods and the first paint-on-glass feature film, The Crossing, have been nominated at the César Awards in France.

A haunting and well-made piece, Aegean Sea, gives us a snapshot of the refugee crisis in Greece. It comes from French motion designer Sophiana Debris-Oliva, who proves once again that motion design deserves more respect.

In America, Reel FX Creative Studios (The Book of Life) dropped a fascinating video on how it’s using Unreal Engine to do real-time CG layout with live actors.

On YouTube, Hungary’s Budapest Metropolitan University has released a few of its top student films from recent years. Check out Betti by Zsuzsanna Ács, about a taxi-driving woman in Budapest (be sure to enable captions).

The Russian animator Ekaterina Sokolova has a deep, three-part interview with the Big Cartoon Festival. It includes her films and behind-the-scenes art.

Starting February 3, the Japanese master Isao Takahata will have a retrospective at the Academy Museum in Los Angeles. It includes his never-released-in-America Chie the Brat. (Thanks to Alex Dudok de Wit for the tip.)

Superworm, created by the always-interesting Magic Light Pictures, was a big hit in Britain. The special’s “premiere on BBC One attracted a huge 40%+ share of viewing,” reports Animation Magazine.

Lastly, there’s that teaser trailer for Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio.

3. Quick look back — Opening Night

When animation was younger, it was less specialized. The people making it weren’t always steeped in it — or even trained in it. They sometimes came from other backgrounds, which informed their work and led them to solutions that someone with an animation education might never have imagined.

Take Nikola Kostelac, an architect in Yugoslavia. In the 1950s, he moved into cartoons after having “fallen in love with animation,” according to historian Ronald Holloway.1 Kostelac helped to manage a series of famous animated commercials in the mid-1950s. Afterward, he and the rest of the team graduated to making theatrical cartoons.

Kostelac’s satire Opening Night (1957) was one of the first and most influential of these cartoons. Holloway called it “a major breakthrough” for the Zagreb animators. When it appeared at the Oberhausen and Cannes film festivals in 1958, it was something of a sensation, helping to bring “international recognition to the young Zagreb Studio.” It was among the projects that created the very idea of the Zagreb School of Animation.

But that doesn’t prepare you for how weird the film is. From the standpoint of traditional animation, there’s little sense to the way that Opening Night looks and moves.

It uses a mid-century modern style, but not like a UPA cartoon. Although Kostelac’s team designed and drew the characters as graphic shapes, every movement distorts them. The principles of animation fly out the window — characters slide from pose to pose in a stop-start way that’s at once funny, surreal and off-putting. Seen today, the style looks almost like vector animation generated by a rogue AI.

That offness was crafted by hand, though, and the result was somewhat revolutionary. Kostelac’s cartoon “paved the way for further artistic expression,” in Holloway’s words. Even other Zagreb directors were taking notes.

With help from the animation historian Toadette, we’ve tracked down a copy of Opening Night. It’s definitely not a film for everyone, but it teaches plenty of lessons about bending the rules of animation to creative effect. (The opera singer’s “great mouths” are a highlight.) You’ll find it below:

4. Last word

And that’s it! Thanks for reading today’s issue. We hope you’ve enjoyed.

If you missed our previous issue, When an Animation Master Disappeared, it’s one we’ve been building toward for a while. It explores the lost years of artist and director John Hubley — one of the most important voices in animation history.

For a time in the ‘50s, the Hollywood blacklist ended Hubley’s career and he went underground. Using a range of sources new and old, we try to piece together what happened, and how he clawed his way back to the light.

See you again soon!

From Holloway’s rare book Z is for Zagreb. We relied on it and his even rarer O is for Oberhausen for our piece on Opening Night.

I just discovered your article about my father, Roy Morita, yesterday! Thank you so much for your kind and positive article about him! He has been gone since 1984 and it is so touching that he is still remembered for his animation work. He was not only very talented but hardworking as he was always picking up freelance projects in addition to his main day job. I remember that most evenings he could be found in his home studio working or quietly sitting in our atrium with a clipboard in hand, sketching. I remember walking by him in his studio as he would be working away on the most detailed drawing for an animation project and it was always amazing. Thank you for your detailed article about his role at Jay Ward Productions and career. I really appreciate it!

Holy moly! It's stories like Roy Morita's that have me so excited to support a magazine like this. Just wow. Incredible share. Thank you so much for putting this out there. I work at a studio and I see this all the time. A quiet genius who is responsible for all the design, and gets no recognition. Not that recognition is what it's about, but someone like Roy!??!?! Dang!!!! Also, thanks for the tip on the Academy museum featuring Isao, will def be going to see that.

Best,

Dar