How Worthikids Makes Hit Animation with Blender

Talking process with Ian Worthington, creator of 'Bigtop Burger' and beyond.

Happy Thursday! This is a really special issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Today, we’re chatting with Ian Worthington (Worthikids) about the way he animates in both 2D and 3D with Blender.

Independent and self-taught, Worthington has become one of the most respected animators online. He’s built speed for years, first in fan animations and then in breakout originals like Witches on Tinder (2019). More recently, he’s had impressive success with personal projects like Bigtop Burger and Captain Yajima, and has done client work for Adult Swim.

One secret to Worthington’s success is Blender — especially its Grease Pencil tool, which lets him draw 2D art in a 3D environment. Blender, which is still free, recently powered Jorge R. Gutierrez’s Maya and the Three. It’s also creating an exciting new era for DIY animators, and Worthington is exhibit A.

In this interview, Worthington breaks down the why and how of his Blender process. He talks about his pipeline for 2D animation with the Grease Pencil — and tells us the reason that Bigtop Burger, a 3D series, looks so much like his 2D work. You’ll find all that and more below.

Enjoy!

Animation Obsessive: How did you start using Blender? Was there an “aha!” moment when you decided to make it your primary tool?

Ian Worthington: I’ve been a Blender user most of my life! I’ve always had a copy of it around. I even used it in my earliest animations for simple compositing; with the character animation done in Flash, then exported as a PNG sequence. After Blender introduced the Grease Pencil, I decided to cut out the middleman and animate straight into Blender! I have not looked back since, I do not care for Flash...

You’ve built quite a reputation for using the Grease Pencil to animate in 2D. What did your first attempt at a Grease Pencil pipeline look like? Was there a major learning curve coming to it from other programs?

The early versions of the Grease Pencil were a bit rough, but within a few months the tools had surpassed all my expectations. I was quite happy to switch.

For my initial workflow, I liked the idea of having the shots laid out in a row, scrolling past the camera in increments. Then if I wanted to “cut back” to a shot, the background and foreground elements were already in place. This isn’t very efficient, but I liked the way it looked and my animations were pretty short anyways.

Could you give us a step-by-step breakdown of your current pipeline for a typical 2D project, and which programs you use for each stage?

For something like Wire, first I draw the storyboards in Blender. I keep them fairly simple since they’ll only have to make sense to me. Then I’ll do a rough animation pass on top, really just filling in any drawings that I think will be too difficult to freehand later.

Next is character animation. Each character is an individual Grease Pencil object so I can translate them around if I need to. Each shot is its own Blend file, with the materials linked between them.

I don’t do backgrounds until the very end when I know how all the characters will move. The backgrounds are the only element I draw outside Blender; I much prefer doing them as raster art in Clip Studio Paint. Then I can import them into Blender as “Images as Planes” and place them in front of or behind the characters in layers.

The Bigtop Burger series emulates your Grease Pencil look, but it actually features a lot of 3D. Could you explain how you use 3D animation in a way that captures the design and motion of your 2D shorts?

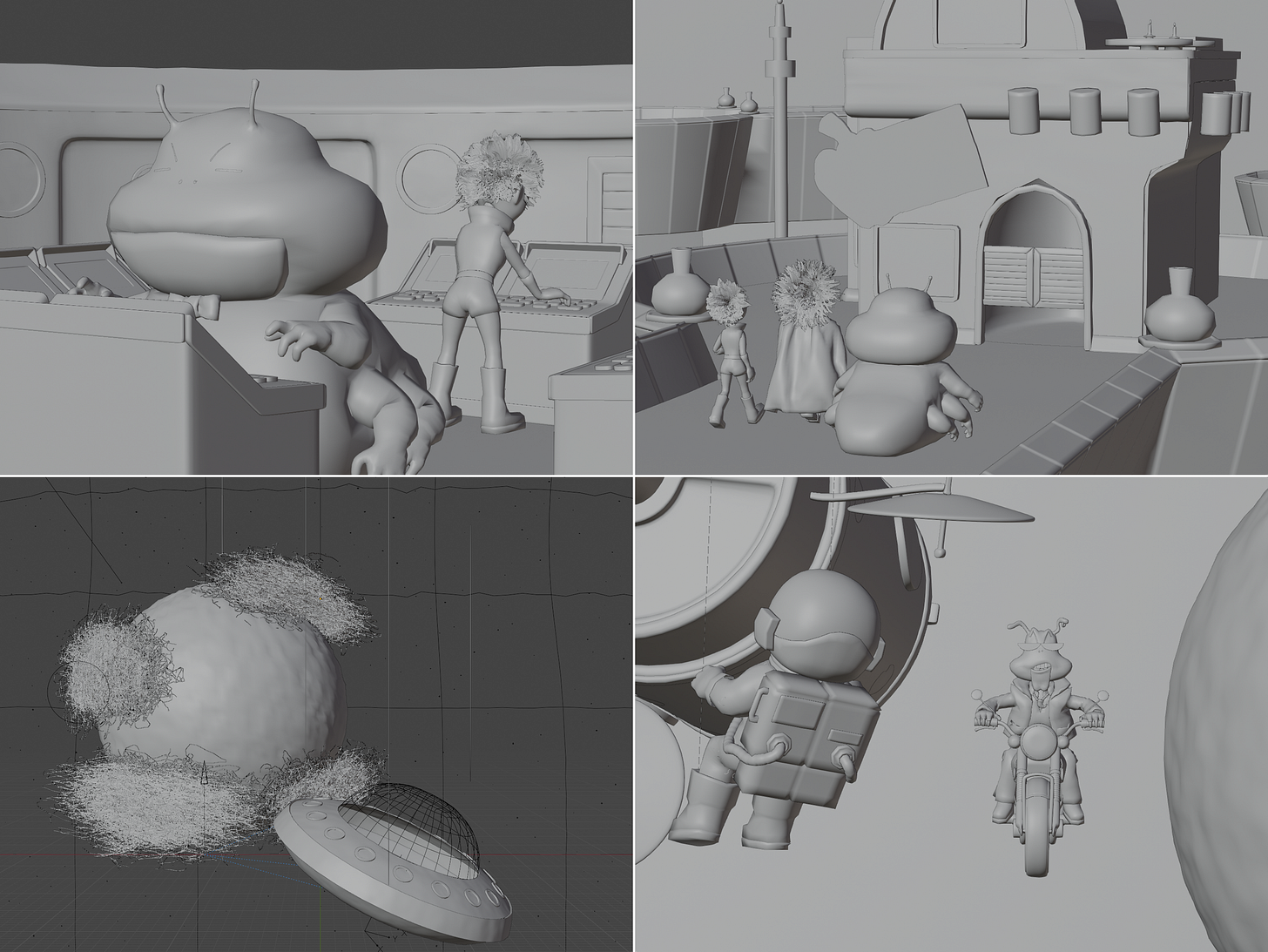

Yes, most of Bigtop is 3D. Only the faces are animated in 2D. There are some static 2D elements attached to the characters, like Penny’s earrings — as well as everyone’s hair, which is a mix of 3D and 2D pieces glued together.

I think people look at the faces first and foremost, so as long as they’re hand-drawn it hopefully gives the illusion of 2D-ish-ness. I also use displacement modifiers to make the characters kind of bumpy, and move the displacement around to give a shimmering effect. I think aberrations and imperfections are the beauty of 2D animation.

Alongside the 3D in Bigtop Burger, you’re also known for your 3D shorts designed and animated to look like Rankin/Bass stop-motion films. How did this style come about, and what’s the secret to matching the look — like the handcrafted quality of the hair and cloth — so closely?

I got the idea, ironically, after watching Nutcracker Fantasy (1979), which isn’t a Rankin/Bass film. It’s made by Sanrio and I believe the director used to work on Rankin/Bass projects, so it’s got a very similar style.

I always enjoyed the Rankin/Bass specials growing up but I’d never considered the possibilities of the aesthetic. Nutcracker Fantasy explores more thoughtful and moody storytelling with that look.

I became a little obsessed with recreating the look. I guess I still am… (laughs)

Each attempt is a learning experience. I keep finding new details I want to try and emulate. I think the secret lies in the details; no one element seals the deal. The shots all look very phony at first, then gradually less so as details are added — all sourced from reference. I’ve collected thousands of screenshots from Rankin/Bass films. Like... almost four thousand (laughs). Just a little obsessed.

Do you find yourself building your work around Blender’s strengths and weaknesses, or does the program go wherever you need it to go? Have you ever started a project that proved to be too ambitious for the tools?

I do find myself incorporating the newest features into my workflow, usually because I think they’re cool. The new Grease Pencil Line Art modifier is way better than Freestyle lines, and I’ve even been experimenting with Geometry Nodes to achieve certain effects.

As far as hitting Blender’s limitations, it’s quite hard to do. My own projects are rather small compared to what the Open Movie team is doing, and Blender’s own limitations seem to expand outward with every update. It’s hard to catch a bug that isn’t fixed by the next version.

You keep up a steady output of high-quality work, despite creating almost all of it by yourself. How do you streamline project and time management? Does using Blender help in this regard?

I don’t have a good answer for this. I’m still quite bad at it (laughs).

If my output seems consistent, that’s a happy accident. In my own life I work very inconsistently. Projects go very fast when I’m actually working on them, but completely halt when I’m distracted.

I think a lot of animators can relate that maintaining physical health is so important in having the energy for animation — but it’s easy to overlook. Sitting at a desk all day is paradoxically kind of exhausting...

Finally, what advice would you give someone looking to start making independent animation with Blender?

Start incredibly small — having huge ambitions but no experience is a bad spot to be in. I have to scale my own ideas back all the time. You can always work your way up to your big dream project.

We’d like to thank Ian Worthington for taking time out of his schedule to chat with us. If you want to go even deeper into his Grease Pencil pipeline, we recommend his video tutorial How to Make a Cartoon — more than an hour and a half of animation process talk. There’s also a quicker time-lapse for his short Palpatine’s Journey.

If you missed our previous issue, it dives into another tool that’s empowered DIY animators — the most important animation book ever written. We look at how Preston Blair’s Animation came to be, and how this inexpensive little guide taught generations of artists across the globe.

See you again soon!

So Very Cool...

So cool!!