The Most Important Animation Book Ever Written

Plus: global animation news and Hayao Miyazaki on 'The Man Who Planted Trees.'

Thanks for joining us! It’s Sunday, and that means another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s what we’re doing today:

One — how one book changed animation around the world.

Two — the week’s animation news, globally.

Three — today’s loose ends.

Four — Hayao Miyazaki on The Man Who Planted Trees.

We publish every Thursday and Sunday. If you’re new here, you can sign up for free to receive our Sunday issues in your inbox every week. It’s quick and no-effort:

But enough about that — let’s go!

1. The little book that could

What’s the most important animation book ever written? It’s a question that could start a fight, with an answer that changes depending on where you live. The Illusion of Life and The Animator’s Survival Kit are clear contenders. For some, it’s The Profession of Animation by Fyodor Khitruk.

Based on influence and impact, though, we feel that nothing can rival Preston Blair’s Animation.

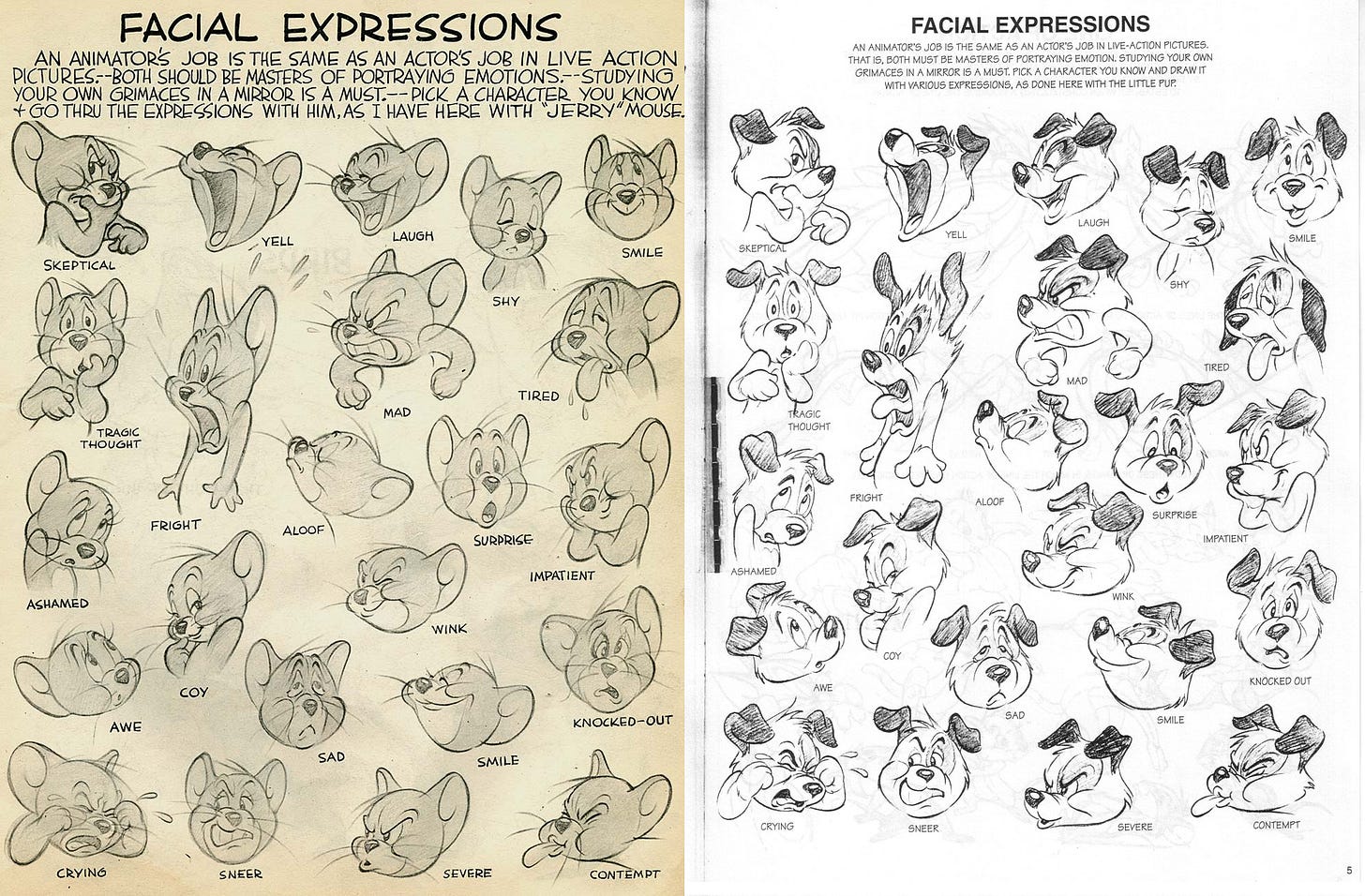

Blair’s book is so universal that it’s easy to take it for granted. Since its first printing in the late ‘40s, it’s always seemed to just be there — the default for every beginning animator. It’s cheap and widely available. Why make a big deal out of something so obvious?

Animation isn’t perfect, either. Animator Richard Williams didn’t gain much from it. “I was put off by the squashy-stretchy 1940s cartoon style,” he wrote. Blair’s advice is deeply rooted in the aesthetics of the time — right down to the “graphic dead end” of treating circles as the be-all and end-all of animation, per the book Cartoon Modern.

And yet none of that changes its importance. Blair’s book touched animators across time and distance. It reached children and struggling artists in America, but it also crossed oceans, guiding animators in places like Japan, China and Yugoslavia. Even the founders of Pixar learned from this book. And we’re going to dig a little deeper into it today.

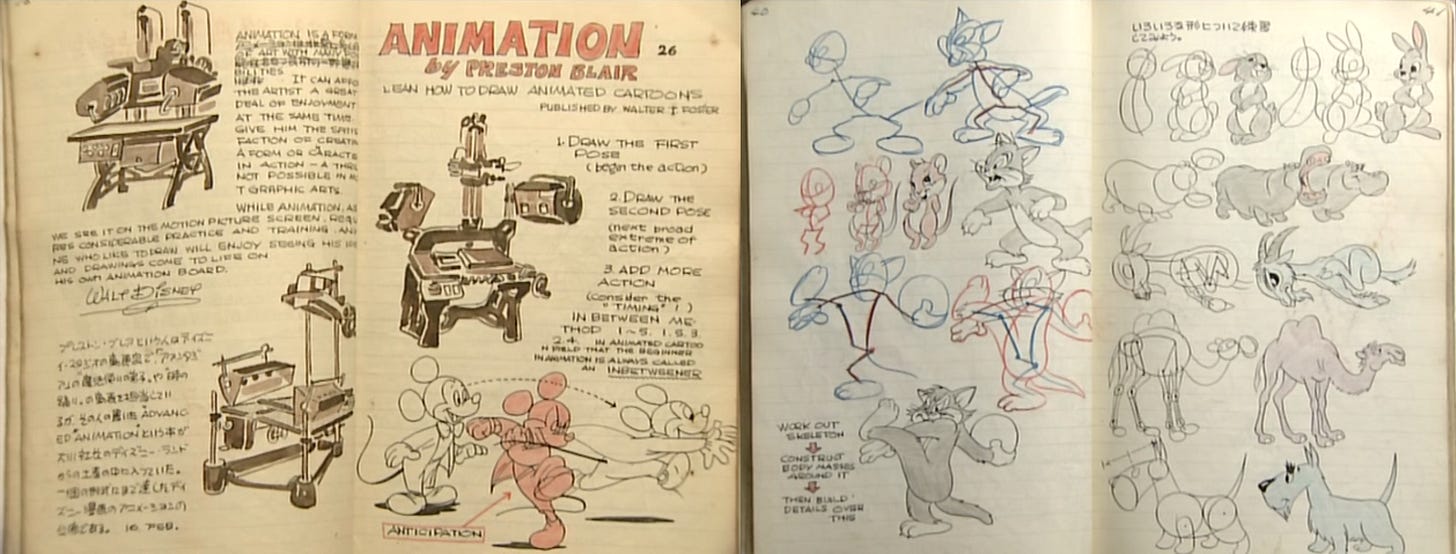

Animation wasn’t the first how-to-animate book. It wasn’t intended to be a classic, either. A man named Walter T. Foster released it in a line of “inexpensive guides to drawing and painting to be sold through art supply stores,” according to historian Howard Beckerman. The book, originally published as Advanced Animation, was a companion to an earlier beginner’s guide called Animated Cartoons.

The idea arose naturally. Preston Blair was a veteran animator, known for his work at Disney and MGM, and Foster was looking for talent. The two met at the National Print Exhibition in Laguna Beach, California. Blair recalled:

I had won a first prize and Foster was interested in me [...] Soon the talk got around to animation and the idea of the book was discussed. In all of the studios I had worked in, the animators used to save examples of good animation cycles, such as walks, runs, skips and so forth, and I collected them. I always thought that they would make a good book and here was an opportunity to find out.

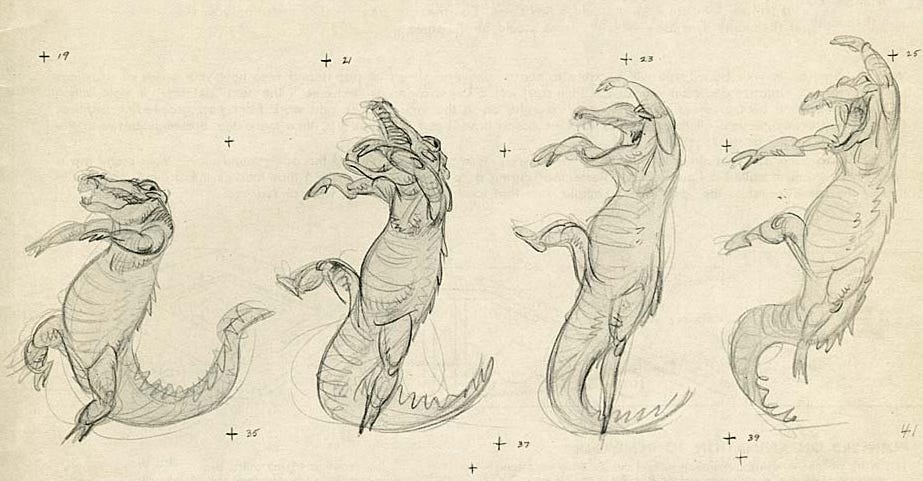

Advanced Animation was made according to the Foster template, right down to the hand lettering. For the art, Blair reused many actual materials he’d drawn at work, including sketches for Red Hot Riding Hood. A few pages feature alligators he’d done for Fantasia that were reworked in the final film. It retailed for $1 (a little over $11 today).

The story of what happened next is somewhat famous. “I was so used to dealing with the studios’ characters that I thought I had free use of them,” recalled Blair. When it was published, Advanced Animation was a work of massive and accidental copyright infringement. Before long, it was pulled, the copyrighted characters were redesigned and the book was republished under the name Animation.

And that was essentially that. Blair and Foster had made a short, cheap book that covered the fundamentals of animation in a brisk and informal way. It was a Foster product, and Foster products were “intended mainly for amateurs, students and kids,” Beckerman pointed out. Animation wasn’t fancy. But it was enough.

Animation quickly and quietly began to change things. Artist Pablo Ferro, freshly emigrated from Cuba, found it a few years later as a “dog-eared library book” in New York — and he used it to teach himself animation. He would become a force to be reckoned with, working on everything from the NBC peacock to the opening titles for Dr. Strangelove.

Self-teaching through Blair grew as a trend. “The only text book I had was Preston Blair’s animation book,” remembered the legendary Floyd Norman, who worked at Disney. Michael Sporn, known for beautiful films like Abel’s Island, also owned it in the ‘50s. He called it “good and cheap” and “very helpful for an amateur like me.”

All of those artists worked in America. Blair’s book, though, started to escape America’s borders almost as soon as it was published.

In communist Yugoslavia during the early 1950s, a team of artists was trying to make a cartoon in the city of Zagreb. Nobody knew what they were doing — they were “frantic to get some kind of information on how to animate,” wrote historian Ronald Holloway.1

Blair’s book reached them, too. As one historian has documented, the writer Louis Adamic, born in Slovenia but living in the United States, mailed the Yugoslavs an English copy of Animation. Per Holloway, “It became the Bible of Zagreb’s young artists.” Over the course of a year, they learned on the job and made a film. It wasn’t great, but it was something. And it set the course for their groundbreaking work to come.

Animation traveled to even more unexpected places. A Chinese animator encountered the book while studying abroad during the ‘50s, and he took it home with him when he returned to Shanghai. According to one expert, it introduced the concepts of “overlapping action and follow-thru” to artist Ma Kexuan, who became one of China’s greatest animators — contributing heavily to projects like Three Monks.

And then there was Japan.

During a visit to the United States, the director of Toei’s seminal Panda and the Magic Serpent (1958) purchased a copy of Animation.2 When he brought it back to Japan, it had a powerful impact on a promising young animator named Yasuo Ōtsuka.

Ōtsuka borrowed heavily from Blair’s book — he even made his own hand-drawn copy of it. It was a huge part of his animation education. Ōtsuka became one of the most important, most influential animators in Japan’s history. He worked with Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata on a slew of projects, defining the look of the original Lupin the Third series, The Castle of Cagliostro and more. “Anime-style” motion owes a lot to him.

And so the spread of Animation continued, around the world and across time. Pixar’s co-founder Alvy Ray Smith learned from it. (“I taught myself animation, as have many, from the great Preston Blair’s $1.50 how-to book,” he said.) The renowned animator Sandro Cleuzo found it at the age of 14, while living in Brazil.

Blair once admitted, “I even use that stuff myself when I have to animate a skip or whatever.”

There were edits to Animation over the years. Blair published a companion called How to Animate Film Cartoons in 1980. He continued to refine the formula up through his final book, Cartoon Animation (1994). Even in that last one, though, drawings from the original Advanced Animation crop up again. The first book is immortal.

Animation’s immortality is partly thanks to the quality of what Blair offered, but not only that. It’s key to remember that this book has always been there. It was and is cheap and widely distributed. It’s short and accessible. Countless animators have used it as a starting point when they couldn’t have gotten an education any other way.

Blair’s book was designed as a mass-produced guide for “amateurs, students and kids” in the ‘40s. In the end, it turned out to be the ultimate weapon against elitism and gatekeeping in animation.

Today, Animation and its offshoots are more available than ever. Even the long-lost Advanced Animation is at your fingertips — back in the 2000s, a scanning project by the ASIFA-Hollywood Animation Archive put the book online. You can find a copy here, and one of the redrawn Animation here.

Looking at it now, some of what Blair’s book teaches is old-fashioned. And it won’t make you a great animator by itself. Yet that was always true. None of the great artists who learned from Blair spent their careers copying him verbatim. His work is a learning tool, and a hurdle to overcome — a hurdle that’s been there for almost 80 years, and hopefully for many more to come.

2. News around the world

Will The Animation Guild prevail?

The moment of truth is nearing for The Animation Guild. After months of pressure campaigns, it’s set to resume contract talks with Hollywood on February 14. As Deadline reminds us, the Guild “paused” negotiations back in early December, and they’re only now starting again.

The Guild is playing a stronger hand than usual. It turns 70 this year, but its members are more energized than they’ve been in a long time, and their ranks have grown. The Guild recently reported that its membership is “at an all-time-high,” surpassing 5,000.

Then there are the Guild’s headline-making power plays — like the recent unionization of Titmouse New York. The Guild and its members have drawn an unusual amount of public attention to negotiations this time around, at a moment when overwork and fair compensation are hot topics across the country.

That continued this week, when the Guild circulated a viral petition for animators and public supporters to sign. There were large Twitter discussions about burnout, and Rachel Gitlevich, who was key to unionizing Titmouse New York, shared the secrets to starting an animation union. Meanwhile, even animators outside any union at all are publishing their salaries anonymously.

The stakes for the Guild may be high, but it has momentum in its favor. Only time will tell if that’s enough.

Best of the rest

Ireland’s Cartoon Saloon seems to have hit a new milestone with its upcoming feature, My Father’s Dragon. Clean-up artists on the film report that they’ve just wrapped up their part of the work.

The Romanian cult classic Delta Space Mission is getting a restored release, in English and in 4K.

Britain’s decision to cut funding for children’s TV, animated and live-action, continues to receive blowback. In good news, the mayor of London announced a new skill development program that includes support for animators.

The government of India is planning a “promotion task force” for animation, comics, games and VFX. Animation studios in the country are voicing approval.

In America, AT&T’s disastrous run with WarnerMedia continues. Going back on earlier plans, WarnerMedia will now be spun off, “rather than split-off,” to merge with Discovery. AT&T’s stock dropped around 5%.

A newspaper in Ukraine, which is increasingly under threat of invasion, covered 10 major women in the history of Ukrainian cartoons last month.

Submission deadlines are approaching for a bunch of animation festivals, among them Annecy in France. The Quickdraw Animation Society has the story (and just opened submissions for its own GIRAF 18).

A middle-school teacher in Korea seems to have been playing the first part of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Memories for his classes for the last 20 years. Now, he complains, attention spans are so short that students won’t sit through it.

Four top publishers in Japan, including Kodansha and Kadokawa, are suing Cloudflare for enabling piracy of their products.

Lastly, in this week’s oddest item, Taiwan’s Ministry of Education made a cutesy animated PSA about “new-style drugs” hidden in coffee and other substances. It has English subtitles.

3. Loose ends

Thanks for reading today’s newsletter so far! We hope you’re enjoying it.

If you missed our previous issue, Yuri Norstein’s Despised Masterpiece, it’s quite a ride. In the late ‘90s, Norstein crafted some of his best-ever animation for a children’s TV series. His reward was the biggest backlash of his career.

We look into how Norstein made this piece and why people hated it, and why it still deserves your attention today. It’s a story about art and business, the artist and the public — and it’s rarely been covered in English. This is the most complete account you’ll find online.

Lastly, we’re doing something new this week. The fourth part of today’s issue is exclusive to members. We explore what Hayao Miyazaki has written about the animated classic The Man Who Planted Trees — and how it ties into his philosophy as an artist. It turns out that he really, really liked this film.

Members, read on. For everyone else, we hope to see you again in our next issue!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.