Keith Haring in Motion

Plus: global animation news and a bizarre spin on 'Don Quixote.'

Welcome back! We’ve got an exciting edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter lined up for you this week. Here’s what we’re doing:

One — how Bill Davis brought Keith Haring’s art to life for Sesame Street.

Two — animation news from all around the world.

Three — the most bizarre adaptation of Don Quixote ever made.

Four — the last word.

If you haven’t signed up yet, we recommend it! Catch our newsletter in your inbox every Sunday, for free:

Now, let’s begin!

1. Keith Haring, animated

“The public has a right to art,” Keith Haring wrote in his journal in 1978. He lived by that maxim. During his short career, he lit up the public’s imagination with his kinetic, iconic style. Like Jean-Michel Basquiat, he brought street art to galleries — and rebelled against art-world elitism. As Haring put it:

The public needs art, and it is the responsibility of a “self-proclaimed artist” to realize the public needs art, and not to make bourgeois art for the few and ignore the masses.

All of which helps to explain how Haring ended up making children’s cartoons for Sesame Street.

It started in the late ‘80s, as the story goes. Haring and Sesame Street were both based in New York, and the team reached out to him through producer Arlene Sherman. Her background was art and experimental film. She had “connections with downtown artists,” she later said — and so she “would think to bring William Wegman on to do something for Sesame Street, or Keith Haring, or those people.” Haring agreed.

Exactly how far Haring got on the Sesame Street cartoons depends on who you ask. He was a quick and prolific artist, sometimes doing 40 graffiti drawings a day, but his time was limited. Haring was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS as the epidemic reached its devastating peak in New York. His output and activism, as a proudly gay artist, only increased in his final years. He made it to early 1990, age 31.

Obviously, Haring’s legacy didn’t end there. But the cartoon project didn’t, either. Another artist took up the task of finishing what Haring had started with Sesame Street — animator Bill Davis.

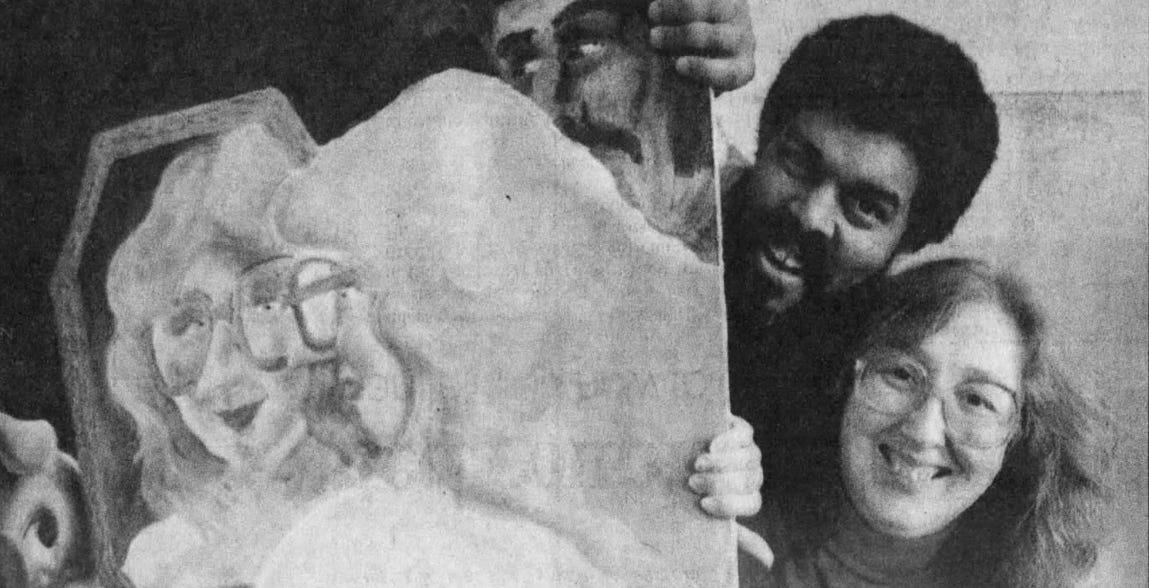

Bill Davis was another New Yorker, based upstate in Ithaca. He and Colleen Davis, his wife, ran an indie animation studio in their house — Artbear Pigmation. Their four children lived with them in the same space. Art covered the walls and doors.

With Bill animating and Colleen painting cels, they freelanced for Sesame Street and more. (In the early ‘80s, Bill even helped to create the opening for Reading Rainbow.) They did do ads, but they favored educational work “that has some value,” Colleen said. Or, as Bill bluntly told The Ithaca Journal, “Jesus, it’s not selling cornflakes.”

In 1991, Artbear Pigmation secured the deal to finish Haring’s Sesame Street project. Before his death, Haring had established a foundation to manage his art and legacy — and that’s what it did here. The Haring-appointed David Stark oversaw Bill Davis’ animation. Davis visited the late artist’s studio, and by year’s end had signed the contracts with Sesame Street. He would do seven shorts in tribute to Haring.

How to move the art was a question, though.

Haring took huge inspiration from Disney, and his paintings and drawings radiate motion. Animation was something he’d “always wanted to do,” he wrote in his journals. But his visual language was almost hieroglyphic — it wasn’t clear how the drawings would actually move. (Unless you’d seen Haring’s hyper-unknown animation Come On, Come On, that is.)

Davis solved this question in Exit — reportedly the first short he finished. It animates a mural that Haring had painted inside a New York children’s club. One commentator noted that “each character [moves] differently based on the pose.” They move rigidly when they look rigid, and take on a “bounce” when they look fluid. Davis adapted motion to Haring’s images like this in every short.

Five of the Davis cartoons use Haring’s hieroglyphic style — Exit, 5 Dancing Men, Dog TV, Babies and Dogs and Telephone. They bring to life Haring’s b-boys, his Radiant Baby, his famous dogs and more. The other two shorts take from Haring’s lesser-known work. In 1–10, Davis animated a coloring book that Haring’s Pop Shop had released in the mid-’80s. 40 Pigs uses a similarly cartoony style.

According to The Ithaca Journal, the Davises usually made over $6,000 for a minute of Sesame Street animation. That’s over $11,000 in today’s money. Around 25% remained after they paid to have the cels shot, and the voices and sound effects recorded.

It’s not clear if the Davises charged more for the Haring tributes — but they don’t look cheap by any means. Still, Davis employs limited-animation tricks that allow Haring’s art to move in creative ways. For example, Davis drew quite a few unique frames in 5 Dancing Men, but he blended them with subtle repetition. It keeps the characters feeling abstract, like icons:

Sesame Street premiered the Haring tribute cartoons between November ‘92 and February ‘93. They would continue to air for well over a decade. Thanks to the Haring connection, their cels and other production materials go for thousands on auction sites today.

As for Bill Davis, he passed away early last year at age 66, survived by Colleen, their children and his many grandkids. He left behind a long trail of classic children’s animation. His name isn’t as well known as Haring’s, but it was his animation that introduced a generation of kids to Haring’s art. Davis brought art to the public, meeting them where they were — and continuing Haring’s legacy of doing the same.

2. News around the world

Kid Cosmic returns

On Tuesday, we learned that Craig McCracken’s Netflix series Kid Cosmic had been renewed for two more seasons. The second season is set to premiere September 7, per Deadline. On Twitter, McCracken noted that Lauren Faust “played a big role in writing and crafting the story” for season 2.

Since it debuted in February, McCracken’s superhero series has received acclaim from critics. But it’s often been buried on Netflix, and it hasn’t picked up quite the same rabid online fanbase we’ve seen for shows like Infinity Train or The Owl House. In a tweet, Faust called Kid Cosmic a “hidden gem” and urged her followers to check it out. We agree.

Cartoon Network and WB Animation step into anime

Also on Tuesday, Cartoon Network and Warner Bros. Animation revealed their plans to start producing anime. Heading the venture is Jason DeMarco, co-creator of Toonami and creative director of Adult Swim On-Air. As DeMarco wrote on Twitter, “When they say ‘anime’ here they mean anime as in ‘created and produced in Japan.’ ”

Cartoon Network and DeMarco aren’t strangers to this. Back in the mid-2000s, DeMarco helped to spearhead IGPX — a Toonami original series made in Japan. And he was partly involved in the second season of The Big O, backed by Adult Swim and produced at Bandai Visual and Sunrise. Even this year, DeMarco was handling co-productions like Fena: Pirate Princess and Uzumaki.

That said, the scope and scale here suggest that Warner is committing heavily to original anime. More and more, companies from Crunchyroll to Netflix and beyond bank on Japanese co-productions. Between this kind of global backing, and Japan’s increasingly international animation teams, anime production isn’t strictly Japanese anymore. That’s been true for quite some time.

Taiwan reaches for the world stage

As we reported a few weeks ago, Taiwan has started to invest in animation — and to revitalize the industry after a few lost decades. At the core of this push is the Ministry of Culture’s foresight program.

Thanks to the Ministry’s subsidies, the channel PTV has launched Omi Sky, Brave Animated Series and Monster Fruit Academy since this June. Per Taiwan’s Mirror Weekly, the three have a combined budget over 70 million Taiwanese yuan, or around $2.5 million. Omi Sky, an educational sci-fi drama for children, took three years to make. (The series’ script accounted for a year by itself.)

Now, Brave Animated Series is the first Taiwanese anime series to reach Netflix — and it’s set to stream worldwide in September. Mirror Weekly bills it as the “flagship” title among PTV’s three projects. Based on a Taiwanese comic and targeted at adults, it’s an action-comedy done with stylized 3D animation. Its budget was around 40 million yuan.

Brave Animated Series has posted impressive numbers in Taiwan, but it remains to be seen whether the rest of the world embraces it. According to PTV, Netflix itself has been hesitant to pick up animation from Taiwan, despite its success with Taiwanese live-action dramas. The series will premiere in English on September 1.

Best of the rest

This week, Sony finally closed the deal to buy Crunchyroll from AT&T. Now, the streamer is set to merge with Funimation, Sony’s existing anime branch.

In Japan, the latest My Hero Academia film is making waves at the box office. A report this week revealed that its “audience is overwhelmingly female — 76.5%.”

Netflix secured the exclusive, worldwide distribution rights for the new season of Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure, the hit Japanese series. It debuts in December.

In Britain, Aardman has signed Gurinder Chadha (Bend It Like Beckham) to direct a new “high concept, Bollywood-inspired” animated feature.

In the first half of 2021, production filings for 50 animated films were submitted to the Chinese government, among them Big Fish & Begonia 2. As is typical, many draw on mythology (Sun Wukong has featured in 24 animated films since 2015).

A third story from Japan. The master manga author Takehiko Inoue is directing an animated film based on his series Slam Dunk. It’s due out next year.

And one last Japanese story. On Friday, as part of a TV event, Studio Ghibli did a long Q&A session on Twitter about Princess Mononoke. Among other things, we learned that the markings on San’s face are actually tattoos.

New data shows that Masha and the Bear, produced by Animaccord in Russia, is the year’s most in-demand preschool series around the world.

Nexus Studios has snapped up Siqi Song, the Chinese-American stop-motion animator behind Sister.

Lastly, The Boss Baby: Family Business was a hit in South Korea. It’s now among the country’s top-seven foreign films of 2021.

3. Quick look back — Don Quixote

Yugoslavia produced very, very unusual cartoons in the ‘50s and ‘60s. The country’s animators were UPA-inspired, state-funded and unaccountable to Soviet censors — since Yugoslavia wasn’t part of the USSR. This blend gave them incredible freedom. No one tested the limits of that freedom like Vlado Kristl.

Kristl was a painter first. When he learned of Zagreb Film’s boundary-pushing cartoons, he joined the studio in the late ‘50s. But he proved almost impossible to work with. Kristl’s process and personality were destructive, and he had a “constant desire to collapse authority in all its forms,” per the Tate. After releasing just two films, Kristl was banned from working on more.

That didn’t stop him. He began to make a guerrilla film of his own — handling the key animation, script and backgrounds himself.

“I made the film without permission and secretly, at night, supported by a few friends and a sales director,” he later wrote. It’s called Don Quixote, but it sees Quixote and his world broken down into abstract shapes. The familiar story is gone. Quixote and Sancho wander a wasteland near a modern highway, before facing off against tens of thousands of small policemen with mustaches.

Despite its bizarre look, this is far from a dry art-film. It’s a manic cartoon about gags — from Quixote’s pratfalls to the way the policemen spill off of plane wings. It’s really “something like a classic Looney Tune,” as the animation blog On the Ones put it. Don Quixote isn’t a film for everyone, but it’s hard not to revel in its audacity. You find a new joke every time you watch it.

We almost didn’t get to watch it, though. “Just as we started to shoot it we were discovered — I was thrown out, the director was dismissed, the film banned,” Kristl wrote. A chance intervention by the Oberhausen Film Festival saved it. With Don Quixote a success, Kristl proceeded to make a live-action short starring himself as a rebel against a Tito lookalike. Escaping to Germany, he never worked at Zagreb Film again.

4. Last word

That’s it for this week! We’ll be back next Sunday with more highlights from the world of animation. Thanks for sticking with us.

One last thing. We popped up in the media a few more times this week! On Monday, the long-running Dutch magazine De Filmkrant shared our piece about Miyazaki and The Snow Queen on its website. Writer Erik Schumacher and the Filmkrant team have our gratitude.

That wasn’t all, though. As part of an article about the place of Nicktoons in animation history, Justin Charity of The Ringer recently chatted with one of our contributors. His piece dropped on Thursday. It takes a few key details from a longer talk, which touched on the influence of alt comix, Gábor Csupó’s background in Eastern European cartoons and more. We’d like to thank Justin for reaching out to us.

Hope to see you again soon!