Welcome! The Animation Obsessive newsletter is back again. This is what we’re doing today:

1️⃣ Looking into Mexico’s stop-motion renaissance.

2️⃣ Animation news the world over.

For those just finding us — it’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues. You’ll get them right in your email inbox. Join 10,000+ readers from around the world:

And now, we’re off!

1: Mexico’s stop-motion boom

Last night, Guillermo del Toro’s version of Pinocchio continued its march to the Oscars. The Annies named it the best animated feature of 2022 — just as the BAFTAs, Golden Globes and others (there’s a long list) already had. Pinocchio is pretty securely the frontrunner for that prize at the Oscar ceremony next month.

Which is exciting for a few reasons. Pinocchio is a good film, and a risky one. It’s defiantly handmade in its look — and its story circles around death and Italian fascism. There’s a reason del Toro spent at least a decade struggling to fund it.

In Mexico, though, there’s an even more obvious cause for excitement. Pinocchio isn’t just a film: it’s a victory in the ongoing revolution of Mexican animation.

Animators in the United States handled most of Pinocchio, but not all of it. Reportedly 3,443 frames of the film were shot in Mexico. A studio in del Toro’s hometown of Guadalajara animated many of the scenes in Limbo and built its ghoulish rabbits. “It was very important to me that the main puppets in the film were touched by Guadalajaran hands,” del Toro said.

This wouldn’t have happened if Pinocchio had been a California-style CG film: right now, Mexico’s industry isn’t big enough to compete in that lane. But it was del Toro’s “bet,” said production manager Aranza Engle, that Guadalajara could match the stop-motion work being done stateside. That the Mexican team’s animation would fit in seamlessly with the stuff made across the border. In the end, del Toro was right.

“Mexico cannot compete against Pixar, which is a gigantic 3D [animation] studio,” Engle told the newspaper El País. “Mexico can compete with stop motion.”

Those 3,443 frames of Pinocchio amount to roughly six minutes, but they tell a bigger story about the state of the industry. Something is going on in Mexican stop-motion, and it’s been building for years. Insiders were speaking of a “golden age of stop motion” even by 2019. Jamie Lang, the editor-in-chief of Cartoon Brew, recently wrote that the “most exciting things in stop-motion animation are happening in Guadalajara.”

To this movement, del Toro serves as a kind of guardian angel. He was at it way before America started paying attention. As he’s admitted:

I have been very close to the big bang of modern stop-motion in my country. I have supported groups of animators not only in my hometown, but also in different parts of Mexico. Pinocchio was a solid stepping-stone for the Guadalajara group, which we call, half-jokingly, The Magnificent Seven.1

The Magnificent Seven form the core of El Taller del Chucho (The Mutt’s Workshop), an animation studio and training facility that del Toro helped to set up in 2019, with support from the University of Guadalajara. The Pinocchio scenes originated there.

All of the Magnificent Seven are veterans. Some have been active since the ‘90s, when industrial-scale animation barely existed in Mexico. They’re best known in the underground — for award-winning films with dark, macabre styles. Their names are Sofía Carrillo, Karla Castañeda, Juan José Medina, Rita Basulto, Luis Téllez, René Castillo and León Fernández. Recently, del Toro called this Guadalajara movement the “vanguard of stop-motion.”

Take Sofía Carrillo’s creepy, gruesome, atmospheric Cerulia (2017) — or Tío (2021) by Juan José Medina. Both drew acclaim, and the latter got major notice at Annecy, the world’s premier animation festival. Guadalajara has produced films like these for years. They’re Pinocchio’s ancestors, and its siblings.

The newspaper El Economista has mentioned “an identifiable movement, a school with a common aim,” among Guadalajaran animators. It’s a tight-knit group, developing and spreading a vision unique to them. None of it came easily. Just a few decades ago, said Karla Castañeda, there was “nothing” for animators. They turned nothing into something, helped at key points by del Toro himself.

Rita Basulto met del Toro in the ‘90s. He supported her stop-motion student film The Eighth Day (2000), which had stalled. As she remembered, del Toro “advised us and helped to solve some administrative problems.” That film became a signature piece in the budding Guadalajaran school of animation.

In recent years, the stop-motion boom has spread even beyond Guadalajara. The Mexico City production Frankelda’s Book of Spooks (2021), for example, is one of the coolest-looking animated series of the 2020s. Its directors credit del Toro with their careers, too. He supported their short Revoltoso (2016) on Kickstarter. “The campaign was going very badly. There were about ten days left to the end and we had about a third of the budget,” they recalled. That changed with del Toro’s help.

At one point, del Toro invited them to breakfast, telling them to stay strong. Later, when the chance to do Frankelda came, they held nothing back. In their words:

Some say that doing animation in Mexico is like playing a video game in the extra hard mode. We have one shot. If we are given the opportunity to make an animated series, we have to make the best animated series ever. Not even just for us, but also to open the gates for more animation that can be produced in Latin America.

This tenacity and fighting spirit have always been there in Mexican animation. Without them, the field wouldn’t exist today.

According to historian Juan Manuel Aurrecoechea, Mexico’s first truly industrial animated film company appeared in the ‘50s.2 It was called Dibujos Animados — “the most important studio of the decade and the place where a whole generation of professionals in the medium would be formed.”

The thing was, it was secretly bankrolled by the United States government to the tune of $1.5 million (in the money of the day). It made anti-communist propaganda films.

Nevertheless, Dibujos Animados attracted the Mexican artists who’d been working in animation. It was useful: a well-stocked studio, with great cels and paint and cameras, was suddenly there. They found some of the Americans sent to supervise the cartoons, like Manolin the Bullfighter, useful as well. They learned as much as they could.3

Things took a darker turn later in the ‘50s, when many of the Mexican workers joined the local startup Val-Mar. American businessmen swooped in, using it as an outsourcing studio. The Val-Mar team found itself animating Rocky and Bullwinkle on the cheap, in unthinkable conditions (we’ve told the story before). A memory from artist César Cantón speaks volumes:

When we said to the Rocky and His Friends people: “Hey, our names don’t appear [in the credits] and we do everything here! We’ll go and tell the union that we want you to credit us...” And, yes, they added us, but do you know what they added? Tom, Dick and Harry, only gringo names, and then “and a bunch of brothers.” We were the “bunch of brothers.”

In the mid-1960s, the heads of the studio put the workers on vacation — and vanished. There was no severance pay, and almost all of the equipment was gone. Well over 100 workers, the bulk of Mexico’s animation industry, had organized their lives around this studio. As bad as things had been, they were now much worse.

Yet Mexico’s animators trudged on. Over the next few decades, they set up organizations to support themselves. They made commercials and even a few feature films. Younger artists learned from older ones. A little government support came in. It was a slow process — but, in the ‘90s, it started to bear fruit in a major way. A bold, self-determining new movement in Mexican animation came to be.

It crystallized with The Hero (1993), a bleak 2D film that won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. Director Carlos Carrera made it with help from the infrastructure that’d gradually grown in Mexico. He relied on industry veterans — including a cameraman who’d worked at Dibujos Animados in the 1950s.

The Hero was a watershed. Its win at Cannes helped to legitimize Mexican animation at home and abroad. “Without a doubt, The Hero is the most important Mexican film in the history of the [medium],” wrote Juan Manuel Aurrecoechea in 2004.

Even the senior members of the Magnificent Seven were newcomers when The Hero appeared. Luis Téllez recalled seeing it: “I realized that I should take things more rigorously.” Karla Castañeda still cites it as one of her favorite films.

The Hero’s dark, warped, ironic sensibility resonates in Mexican animation today. Last year, The Mutt’s Workshop brought in the film’s director to teach classes.

All of which takes us back to Pinocchio. Those 3,443 Guadalajaran frames took under two years to create — but decades and decades underlie them. One final story reveals just how closely tied together Pinocchio, this history and Guillermo del Toro truly are.

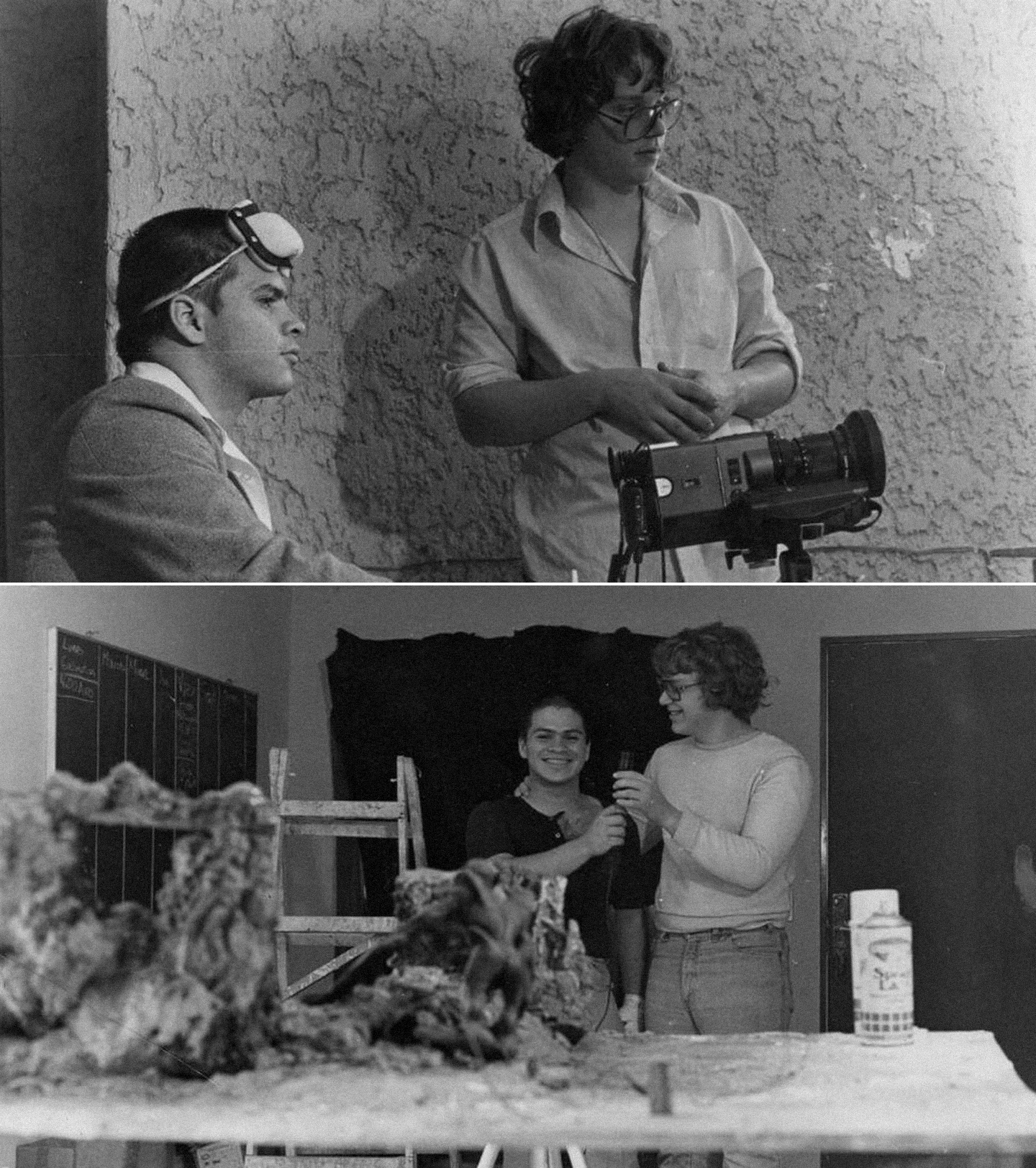

In the early ‘90s, something happened in Mexican animation that was at least as vital as The Hero. According to the book The Lost Episode: History of Mexican Animated Cinema, two Guadalajaran colleges (ITESO and the University of Guadalajara) started hosting animation courses, paving the way for the modern animation scene.

One person teaching these classes was animator Rigoberto Mora, who’d co-founded the company Necropia with del Toro in the ‘80s. Back then, they did special effects, claymation (del Toro started his career in stop-motion). Mora became a central figure in the Guadalajara renaissance. His name appears in the credits to many of the Magnificent Seven’s early stop-motion films.

On the Annecy award winner Down to the Bone (2001), directed by René Castillo, Mora was an advisor. Castillo said this when the Magnificent Seven were interviewed a few years ago:

Everyone here knew Rigo. I believe he was a teacher for all of us. When I started in the field, I heard of someone called Rigo who worked on animation, so I started looking for him and following him. He was someone with great knowledge [... he] left us all with the seed of passion. Passion to do what you enjoy doing. We remember him dearly.

Mora died in 2009. It was a blow to Guadalajaran animation, and to del Toro. Animating part of Pinocchio in Mexico was a way for del Toro to return to his roots, and to continue Mora’s legacy. “Recovering that bond in an active way was substantial for me,” he explained last year. Despite the challenge of setting up The Mutt’s Workshop and filming part of Pinocchio in Guadalajara, del Toro felt it was worth it.

It’s 3,443 frames. Just six minutes of a film. But it’s so, so much more.

2: Animation news worldwide

Leiji Matsumoto, 1938–2023

Just as we were finishing last Sunday’s issue, a major story broke. Manga artist Leiji Matsumoto passed away at age 85. He was such a significant figure, not only in manga but in animation, that Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary gave a statement in his honor. Tributes quickly poured in.

Matsumoto was a sci-fi legend — creating Galaxy Express 999, Captain Harlock and more. The ideas he packed into his manga shaped Japanese animation in the 1970s and ‘80s. In its report on Matsumoto’s passing, the Yomiuri Shimbun credited him with leading the “science-fiction boom” in that era.

Unlike many manga authors, Matsumoto actively involved himself in animation. He took part in the planning stage for the film version of Galaxy Express 999 (1979), which was a huge, era-defining hit. The director in charge, Rintaro, went on to become one of Japan’s most respected filmmakers.

Matsumoto also helmed the animated series Space Battleship Yamato in the ‘70s, and played a key role in the Daft Punk film Interstella 5555 (2003) — a tribute to his work, featuring his own designs. These are just a few of the animation projects he touched.

There’s no way to calculate Matsumoto’s influence. “America owes its anime and manga fandom to the huge TV impact of Star Blazers, the US edit of Space Battleship Yamato,” wrote historian Helen McCarthy in her detailed obituary. She also highlighted just how wide his range really was. Matsumoto’s slice-of-life manga series Otoko Oidon, basically unknown in America, was big enough in Japan that the statement from the Chief Cabinet Secretary mentioned it by name.

Matsumoto’s career was a giant one, as was his impact on culture in Japan and abroad. The world will be unpacking it for a long time to come.

Newsbits

In America, as we mentioned, the Annies happened on Saturday. Watch Craig McCracken accept his Winsor McCay Award for lifetime achievement, and see the full results here (both Pinocchio and Marcel the Shell won big).

One of the week’s most exciting stories came from Japan. Rintaro, now in his 80s, is back with a new film. It’s 25 minutes long and about director Sadao Yamanaka (1909–1938). Katsuhiro Otomo designed the cast. It premieres in March.

If you’re looking to read more about Pinocchio, don’t miss this BBC piece on the British puppet-makers who created the film’s main cast.

In India, the ever-great Vaibhav Studios has a new ident series for Cartoon Network. See two here and here.

The Chinese film Art College 1994 has a subtitled clip out. It’s similar in style, vibe and cleverness to Have a Nice Day (2017) by the same director — a very good thing.

Director Makoto Shinkai feels that Chinese animation will “overtake” anime. In his words: Japan’s animators were once “very confident that they were creating the best and most unique animation movies in the world […] But I think that this has changed in recent years, and most of my peers think that way as well.”

In France, the film My Sunny Maad was named Best Animated Feature at the César Awards.

Austria is introducing “two new funding programs that could cover as much as 60% of costs for international feature film productions,” according to Variety. That includes animated projects.

The Japanese documentary series 10 Years with Hayao Miyazaki, four hours in length, got picked up for an international release by GKIDS. It’s exciting — maybe the 400-minute masterpiece How Princess Mononoke Was Born can be next.

Lastly, we wrote about the use of unscripted dialogue in animation — specifically in the case of Aardman.

Until next time!

From the Pinocchio artbook.

As he explained in his book The Lost Episode: History of Mexican Animated Cinema (El episodio perdido: historia del cine mexicano de animación), which was our main source for the material on Mexico’s history with animation.

A bunch of Americans cycled through Dibujos Animados. One of the most important was animator Emery Hawkins, an ace artist during the 1950s — “with him we learned a lot,” recalled a member of the Mexican team. The Lost Episode contains fuller details.

https://www.reddit.com/r/Miyazaki/comments/cgse9x/looking_for_the_englishsubtitled_how_princess/

that link has the first three parts to "How Princess Mononoke Was Born".