We've Made a Rare Animation Artbook Free to All

Bringing back 'Cartoon Modern,' plus retro ads.

Happy Halloween! This is a very special edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. We’re treating you to a free copy of Cartoon Modern — a rare, out-of-print artbook on mid-century animation. You’ll find it linked below, as part of today’s lineup:

One — Cartoon Modern and the meaning of mid-century cartoons.

Two — the retro ad of the week.

Three — the last word.

If you’re new here, you can sign up to receive our newsletter right in your inbox, every week:

We won’t waste any more time — let’s go!

1. Reviving Cartoon Modern

Many of the best animation books are rare. They have a small print run, sell to a core audience and then disappear. On eBay and Amazon, second-hand copies go for hundreds. Only a tiny group gets to see the inspiring art and key information inside.

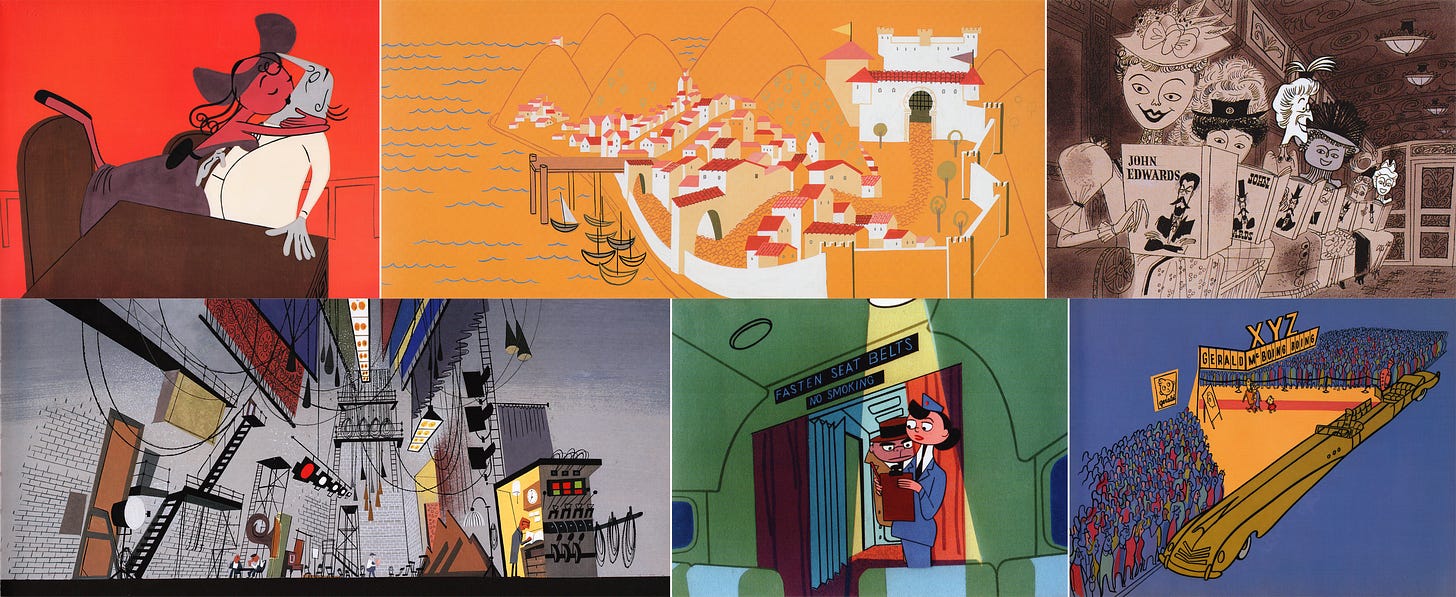

A major example is the artbook Cartoon Modern: Style and Design in Fifties Animation.

Released in 2006, Cartoon Modern is the guide to the so-called “UPA style.” It’s full of art and production insights you can’t find anywhere else. The whole mid-century cartoon movement is here, from UPA to Mary Blair to Sleeping Beauty and beyond. On the back, you see a blurb from Craig McCracken of Powerpuff Girls fame:

Besides the fact that it’s filled with tons of incredible, inspiring, and intimidating artwork, Cartoon Modern is impressive to me because it goes beyond the studios and really focuses on the fact that these cartoons are all made by unique and individual artists. I’ve been waiting a long, long time for a book like this!

The author of Cartoon Modern, Amid Amidi, owns the book’s copyright and digital rights — and has written that he wants to see it reborn. “Would be delighted if someone scanned in and made available a high-quality PDF of Cartoon Modern,” he tweeted in 2019. “Book has been out of print for a long time and should be readily available to all.”

So, that’s what we’ve done. You’ll find a link to the full book at the end of this piece.

Before we get to that link, let’s talk a little about what Cartoon Modern can teach us.

As this book makes clear, UPA didn’t have a monopoly on mid-century modern design in animation. The studio’s idea that cartoons could take any form, that “style stemmed from the film’s subject matter,” won over the whole industry. Everyone took from it. In the book’s words, UPA “formed the foundation of the design movement in 1950s animation.”

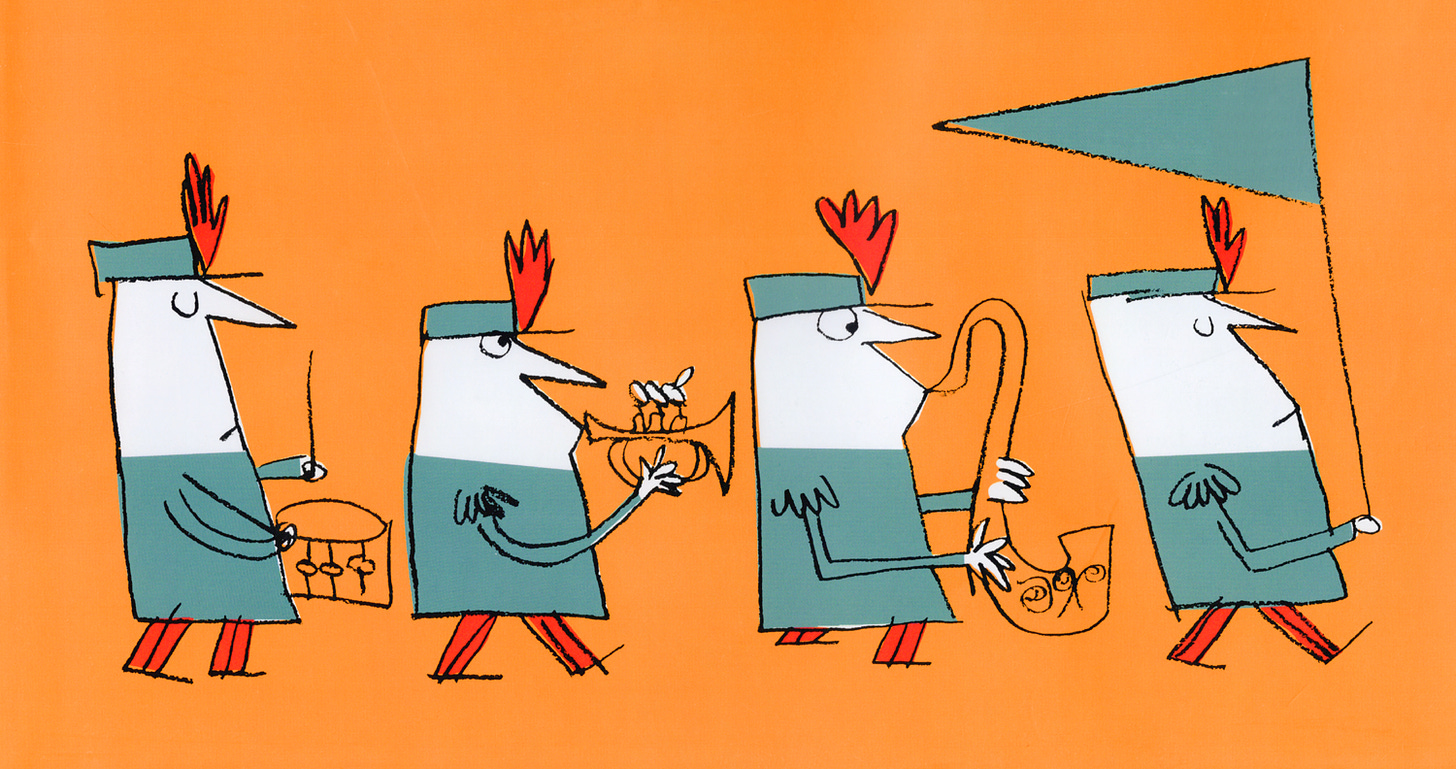

You probably know UPA’s Gerald McBoing-Boing. But what about Terrytoons’ Flebus and The Juggler of Our Lady? Both are wonderful films with a mid-century look — but neither looks quite like a UPA project. UPA’s impact was so big that it went beyond individual films or styles. An ethos entered the water supply, changing the nature of animation. Cartoon Modern quotes the historian Michael Barrier:

[UPA was,] in the early fifties, exactly what the Disney studio had been in the thirties: the reference point, the studio with which every other studio automatically compared its cartoons, whether or not a given studio was trying to emulate the UPA films.

This brought industry-wide changes not only to design and motion, but to subject matter. Human characters and modern-day issues came to the fore. Cartoon stories got more focused, relying less on loose chains of gags and more on concepts or messages.

There was a political aspect to UPA’s ideas, too. Many of its core members, like John Hubley, had left-leaning politics. Their views were apparent in the artists they promoted and in their films (Cartoon Modern even recounts a bit of Red Scare hand-wringing toward Disney when it adopted a mid-century style). Both had ripple effects.

For one, UPA broke with vaudeville and lowbrow comedy — big influences on older animation. The studio hated “hurt gags.” Meanwhile, Hubley called Mr. Magoo a satire on “thickheaded conservative[s].” And one of UPA’s “seminal early works,” per Cartoon Modern, was “Brotherhood of Man, a film that advocated racial equality.” UPA cartoons thought differently, and it didn’t go unnoticed.

Bill Melendez (A Charlie Brown Christmas) once wrote that UPA was the only animation house of its era “with enough sensibility and good manners and creative talent to fit the description of being a ‘minority-friendly’ studio.” Melendez, whose real name was José Cuauhtémoc Melendez, was a UPA animator. Cartoon Modern notes that Chris Ishii, who’d been interned during the war, was a creative director.

Part of UPA’s impact came through this influx of people from diverse backgrounds. Cartoon Modern singles out Sterling Sturtevant — she used her talents to redesign Mr. Magoo and art-direct some of his best cartoons. When she left UPA, she joined Melendez at Playhouse Pictures and designed for the earliest Peanuts animation.

Artists from UPA spread across the industry. Another was John Hubley, who lost his job at the studio in 1952 — blacklisted from Hollywood over his politics. After a few years adrift, he and his “front man” Earl Klein founded Storyboard in Southern California. They went into advertising, reaching tens of millions with their hit commercials.

Advertising was, arguably, the definitive place that mid-century modern cartoons took hold. UPA, Storyboard, Playhouse and other studios all worked in TV commercials, spreading their design ideas far and wide. Cartoon Modern again:

Hardly a kids-only marketing gimmick in those days, animated characters hawked anything and everything that could be unloaded onto the postwar-era’s swelling legions of middle-class consumers. During peak years in the 1950s, it has been estimated that one out of every four ads on television was animated.

Those animated ads represented the most-viewed animation of the time, and they looked great. According to Cartoon Modern, an entire episode of a later cartoon like Rocky and His Friends cost $8,520 (around $80,000 today). In 1956, Storyboard charged $10,000 (now $100,000) for one minute of commercial animation — in black and white.

Hubley wasn’t the only ex-UPA artist dodging the blacklist in advertising, and the irony of it wasn’t lost on them. Yet they were doing fantastic work, and diverse voices were key to the TV commercial industry — including Tee Collins, whose design for Elektra pops up in Cartoon Modern. It’s a complicated story.

“Every popular aesthetic has been gobbled up by corporate campaigns,” Bob Flynn, one of our favorite voices in animation, tweeted recently. Then he clarified, “UPA especially!”

The use of UPA’s mid-century modern revolution for counter-revolutionary ends may have reached its peak with John Sutherland Productions. As Cartoon Modern relates, it specialized in right-wing corporate films for Big Oil, chemical companies and more. “Everything I’d thought or suspected about big business turned out to be absolutely true,” said Bill Scott, a UPA employee who went to Sutherland.

“I disliked what I was writing, but I wrote it because the money was good,” the book quotes Scott as saying. “About once a year, I’d get fed up and march into the office and say I couldn’t do it anymore. Every time I’d open my mouth to complain, they’d stuff it with money.”

Sutherland’s films like Rhapsody of Steel were graphically adventurous, even groundbreaking. They also showed how messy the mid-century modern era was — and why artists like Hubley started to move on. We often quote a line from a commentator at the time:

UPA’s high-style technique exploded a trend. Then some UPA employees went off on their own and developed variations and abstractions of the UPA style. Eventually that canceled out the novelty and brought about a “phoney” tinge.

Cartoon Modern chronicles these highs and complex lows. We’ve barely scratched the surface. For more, we highly recommend downloading the book.

One word of warning. As a broad survey of the era, the good art in Cartoon Modern sits beside a handful of bad pieces — ones that remind us again of the messiness of the time. This aesthetic may have started with Brotherhood of Man, but harmful stereotypes and imagery still found their way into some cartoons, including Disney’s Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom. Bear that in mind before you download.

Download Cartoon Modern (compressed .PDF — 319 MB)

Download Cartoon Modern (uncompressed .CBZ — 4.6 GB)

Lastly, technical notes. We scanned Cartoon Modern at 400 dpi, then straightened and carefully color-corrected each page. Our goal was to remain faithful to the book as printed. No scanning job is perfect, but we tried to get this one as right as we could.

That said, if you’re as picky about image quality as we are, you’ll notice that we didn’t descreen the book. Scanning with a descreen filter was too imprecise. So was scanning raw and descreening whole pages afterward. The only way to do justice to the art was to descreen each artwork separately — a step we had to leave to the future, keeping the uncompressed scans crisp enough to allow for later restoration.

Cartoon Modern has been an invaluable resource for us — we hope you’ll get as much out of the book as we continue to. Happy Halloween!

2. Retro ad of the week

Above, we wrote about John Hubley’s commercial work at Storyboard. His ads have appeared in many of our issues. Today, though, we’re taking a close look at a particularly special one — the earliest Storyboard spot we’ve been able to confirm.

Hubley’s studio began humbly in February 1954. (Storyboard’s start date is disputed, but a heap of evidence and a trade magazine from the time support this one.) Back then, his connections were limited. “He had one client, Madman Muntz,” per The Record.1

Muntz was a true West Coast character — a used car salesman and, for marketing purposes, a self-styled lunatic. He invented his own TV set, the Muntz TV, and hired ad man Michael Shore to supervise the commercials for it. Shore recalled pulling in the “towering talent” Hubley to work on them, fully aware that he was blacklisted.

Reaching the airwaves in the first half of ‘54, one of Storyboard’s Muntz ads caught the industry’s attention. It shows the letters of the Muntz TV name dancing, playing and changing shapes — Hubley’s eye for ad design was already sharp. Bill Melendez animated it, having left UPA not long before.

This spot for Muntz isn’t the greatest work that Hubley and his studio would do — but it was smart, solid and different. Before the end of ‘54, Storyboard would land the Heinz and Ford accounts, to name just a few. This ad helped Hubley get there.

3. Last word

That’s all for today! Thanks for reading our Sunday edition. Time constraints forced us to drop the news section this week, but it’ll return next time.

As always, we publish twice a week — every Sunday and Thursday. Our Thursday issues dive into deep, complex animation stories like Katsuhiro Otomo’s storyboards, Hayao Miyazaki’s music video and that time Frank Lloyd Wright inspired UPA with a Soviet cartoon. Thursday material is exclusive to our community of members (paying subscribers).

Membership costs $10/month or $100/year. If you’re a student with a .edu address, you can click here for a 40% discount.

One last thing before we go. Recently, author Robin Sloan shouted out our newsletter in his newsletter, highlighting our Thursday issue about Miyazaki’s music video. We’d like to thank him — and we’re glad he enjoyed.

Hope to see you again soon!

The article “T.V. Ads CAN Be Fun” from The Record (February 18, 1956).

Thanks so much for your hard work scanning this. Looking forward to staring at it endlessly!

Both copies of Cartoon Modern have been uploaded to the Internet Archive, which is easier to browse.

smaller pdf - https://archive.org/details/cartoonmodern/

4 gig cbz of raw scans, for future descreening - https://archive.org/details/cartoon-modern-uncompressed