Welcome back! The Animation Obsessive newsletter returns with more. Today, we’re looking at:

1️⃣ The unlikely story of Princess Arete.

2️⃣ Animation news worldwide.

Animation Obsessive is a reader-powered newsletter. We offer free and paid subscription options:

Now, let’s get going!

1. A personal film against the odds

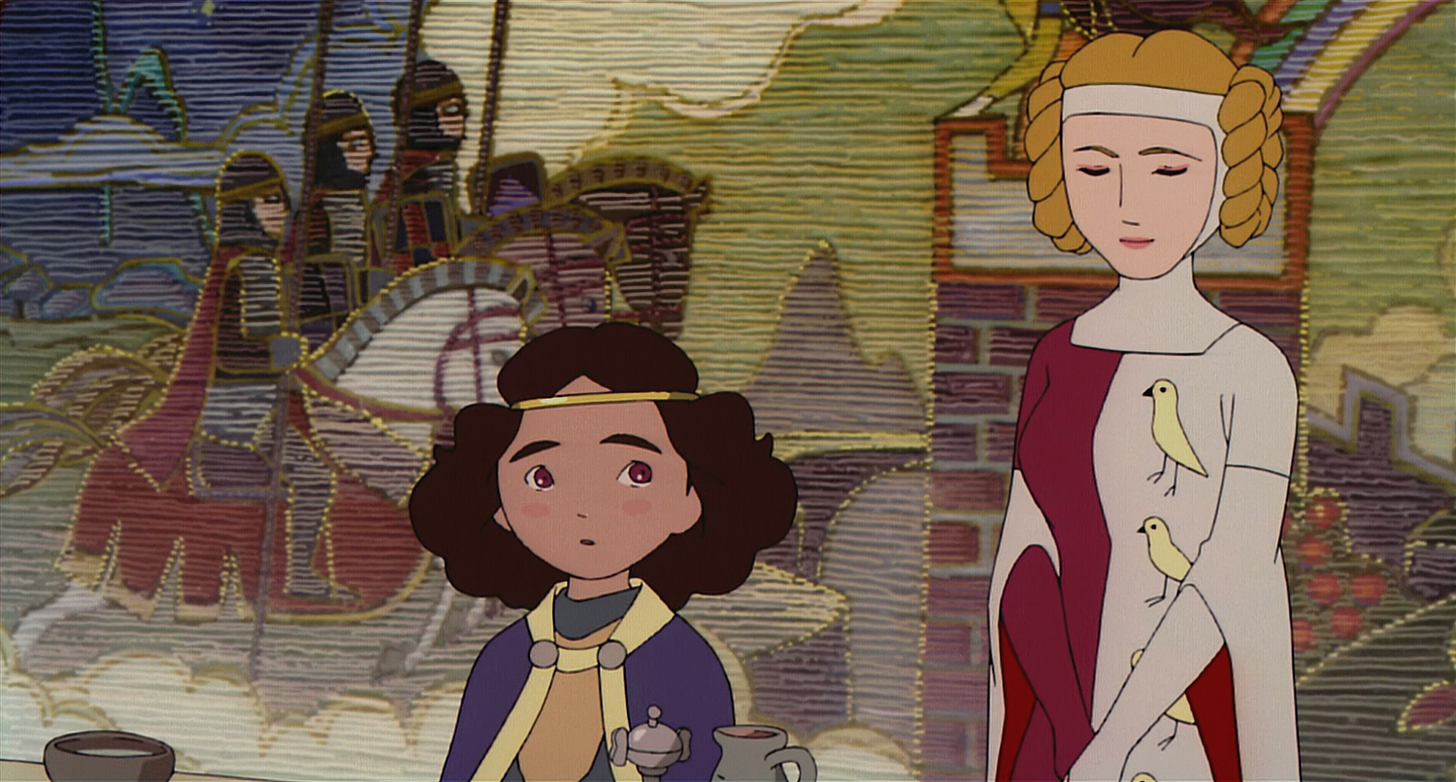

Princess Arete is one of the most underrated anime features of all time. Produced by Studio 4°C, it’s an immersive, gorgeous, atmospheric fairy tale. And yet, ever since it debuted in 2001, it’s been relegated to cult status at best.

The film is about a young princess who’s locked away in a tower, waiting to be married off and dreaming of a life outside her walls. Suitors like “Dullabore” are no match for her. When a wizard curses her and spirits her away, no one comes to her rescue. She has to find her own way out.

The director of Princess Arete, Sunao Katabuchi, was telling a strongly personal story here. He’d hustled for years in anime, even working closely with Hayao Miyazaki, but felt he had little to show for it. This film was his answer, and the turning point of his career.

Until December 2, Studio 4°C has made Princess Arete freely available on YouTube with English subtitles. Region-locking restricts it in many countries (see Catsuka for details), but it’s open for us. It’s an incredible film that deserves to be seen, and this is a rare opportunity to do so. You’ll find it below.

There’s quite a story behind Princess Arete, too, that we’d like to publish in honor of this release. For that, read on.

Once upon a time, long before Princess Arete appeared, Sunao Katabuchi was a talented writer and artist who couldn’t catch a break.

He’d joined the anime industry in the early 1980s, as a college student. Hayao Miyazaki hired him to write screenplays for Sherlock Hound, before that series fell into disarray. From there, Katabuchi joined Miyazaki, Isao Takahata and Yoshifumi Kondō on the ambitious and ill-fated Little Nemo project — a nightmare production, tangled up with Hollywood.

Over two years into his anime career, Katabuchi still hadn’t released anything. When his first writing credit finally popped up on the belated premiere of Sherlock Hound, the press speculated that “Sunao Katabuchi” was simply one of Miyazaki’s pen names.

After all that work, Katabuchi wrote, “My existence was like nothing.”

Things only got worse. After bouncing around the industry, Katabuchi got the chance to direct Kiki’s Delivery Service for Studio Ghibli. He read the original book, took charge of the project and wrote an outline with key similarities to the final film.1

Kiki was planned as a double bill with a live-action movie about women’s volleyball — the idea was to put two young, inexperienced directors in charge of films that appealed to women. That plan changed, but Kiki became even more ambitious. Then problems arose again: investors weren’t interested unless Miyazaki directed it himself. Katabuchi became an assistant director, in charge of technical stuff.

It was now 1989, and Katabuchi still felt like he hadn’t achieved much of anything.

Reading a newspaper around that time, he saw an ad for a new book called The Adventures of Princess Arete. First published in Britain as The Clever Princess a few years before, it was a feminist fairy tale about a girl who made her own way in the world — despite its difficulties. “Ah, I wish I could be like that, too,” Katabuchi remembered thinking.

That was the seed of Princess Arete. A seed that took more than a decade to bloom.

If you’ve never heard of The Clever Princess by Diana Coles, you’re not alone. Its English release wasn’t a blockbuster. Yet, in Japan, the book’s message hit home. “When we first read The Clever Princess,” wrote the group of Japanese women who translated it, “we were very glad to find at last a story of a girl who can tackle and overcome difficulties on her own.”

Armed with a clever tagline (“A princess just waiting is out of date!”) and a bright pink cover, the book “sold extremely well, and went through 8 editions in just the first 3 months,” according to one researcher. Katabuchi recalled seeing it in the papers for several years.

One of the people who took notice was Eiko Tanaka — a production manager at Ghibli who’d co-founded Studio 4°C. She and Katabuchi were co-workers on Kiki’s Delivery Service. As she later said, the “female chief of an animation coloring company one day asked me that she wanted to create a movie from an original novel, The Clever Princess.”

So, in 1992, Tanaka suggested the idea to Katabuchi. Studio 4°C was a modest operation back then — “a very ordinary one-story private house,” Katabuchi recalled. Drawing desks sat on tatami mats. Production staff worked in the kitchen.

Katabuchi agreed, but actually making the movie was another matter. Soon, Studio 4°C expanded and entered full production on Katsuhiro Otomo’s Memories (1995). By 1993, Katabuchi was creating an outline for Princess Arete and hustling to support himself, as he waited for his project to be ready for production.

The first Princess Arete preparation team was just him and Chie Uratani, a key animator from Kiki’s Delivery Service. Katabuchi wrestled with the project, buying books on medieval European castles and trying to find the right approach.

The film took on more and more urgency for him. Katabuchi was in his 30s and experiencing, as he put it, a midlife crisis. What began as an idea for a stop-motion puppet film, tailored to the education sector, grew into something much more ambitious. Princess Arete’s inner strength came to symbolize his dream of retaking control of his life — and of having something of his own to show the world.

“I wanted viewers to find a source of vitality in themselves by watching the film,” Katabuchi wrote. He fiercely wanted to make Princess Arete, and to give that same sense of being able to do something to its audience.

Despite these aims, though, he was still in the trenches. At Studio 4°C, he took a technical job on Memories, overseeing Cannon Fodder’s camerawork. When he helmed his first major project, Nippon Animation’s unsuccessful Famous Dog Lassie (1996), the series quickly vanished.

Even Princess Arete was shelved for a time — until Tanaka approached Katabuchi again. “I’m starting to think that it’s time to get Princess Arete up and running,” she told him. Around 1997, the film finally started to become something real.

Princess Arete’s final budget was shockingly low, and it started out even lower. Part of that might have been the subject matter — the fervor around the book had faded, Katabuchi wrote, and the film made “very little sense from a marketing point of view.” He and Tanaka wanted to do it anyway.

For that to be possible, Studio 4°C had to keep the production extremely lean and precise.

A tiny prep team, including Katabuchi and character designer Satoko Morikawa (Lassie), assembled in an apartment around summer 1998. It had tatami mats, Japanese-style toilets, no air conditioning and no bath. “It was so hot, I thought it was ‘Studio 100°C,’ ” Katabuchi recalled.

In this space, the film began to take shape. Katabuchi bought a TV and started playing films about medieval Europe, like Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring (which inspired the ending to Princess Arete). He also showed Morikawa the work of N. C. Wyeth — whose illustration of Maid Marian became the model for Princess Arete herself.

They drew from everything. Katabuchi built a miniature castle out of cardboard. A picture he took on a recent trip to Zagreb became the basis for Arete’s meal early in the film.

Meanwhile, Katabuchi had a script to write. This was a struggle, in part because he didn’t know where to start. The Japanese edition of Coles’ book had made significant changes to the story, turning it more serious and reducing its black comedy.

Katabuchi, who wasn’t proficient in English, had discovered this by translating a copy of the original book with an English-to-Japanese dictionary. (“It feels like a product of the same country as Monty Python,” Katabuchi realized.) All of his attempts to contact Coles failed. So, he cut his own path.

“I wanted to make Princess Arete not like a Hollywood roller coaster, but like a European film,” he wrote. “With no way to get enough money for production, I had no choice but to think of it that way.”

Princess Arete takes the kinds of liberties with its source material that you might associate with a Miyazaki film. Katabuchi freely blends Coles’ story with a bunch of other sources, including the novels The Tombs of Atuan by Ursula K. Le Guin and Jousai by Japanese author Ryōtarō Shiba. Barring a few charming notes of comedy, Coles’ humor is hardly present. It’s a slow, methodical, meditative film.

It’s clearly not a Ghibli piece, either, despite the studio’s influence on him. He’d learned Miyazaki’s way of making movies firsthand, and he used some of those methods (storyboarding before the script was done, starting production before the storyboard was done) on Princess Arete. But he reached different conclusions.

For one thing, his storyboards were so loose that, when someone brought up the idea of publishing them as a book, that person gave up on the idea after taking one look at them.

The main similarity between Princess Arete and Ghibli is the film’s intricate naturalism and attention to detail. As Miyazaki once said about his own work and Takahata’s:

We just felt that human beings live in the midst of all sorts of things, including a certain relationship to production, so it isn’t right to make films that only depict the feelings and thoughts and human relations of the main characters. What was their source of livelihood? That was something we discussed thoroughly even when we did a TV series like Heidi, Girl of the Alps and then decided to make films with some sort of rationale. It wasn’t enough unless we included the relationship to nature, the environment where the characters lived. At times it may be the season, or the weather, or the type of light. We felt we wanted to be humble in the face of the entire world, the vegetation of nature, and all of it.2

You feel this philosophy in Princess Arete, in the way the backgrounds are rendered. It extends to the glimpses of routine we catch from the background characters, the farmers and townspeople who keep the world running. The film celebrates everyday lives and details — even those of the people who have no dialogue. Arete repeatedly says that life has meaning, but the film also shows it.

Even the movements of the cast, while stylized, are deeply studied and real. Many of the key animators were longtime Ghibli alumni. When Arete takes her stolen book through the secret passages of her tower, in the clip above, you feel every tug on the bed-sheet rope.

Again, though: this isn’t Ghibli. It doesn’t even feel like Studio 4°C. Princess Arete moves at its own pace, with its own logic. It’s extremely slow. It feels like a movie you can live in. You won’t find many anime like it.

Princess Arete was in production for around two years, wrapping in late 2000. According to Katabuchi, it was Studio 4°C’s first project to go fully digital for shooting and paint. The colors are immaculately designed and balanced — without the garish overlays and mushy compositing that sometimes came along with the transition to digital. It has a painter’s sensibility.

For us, the result is a must-watch. That won’t be the case for everyone. It wasn’t even the case when Princess Arete premiered in Japan. Before its release, the press reported that “there isn’t much talk about it so far.” When it came out, it flopped like Lassie — disappearing from theaters without much fanfare.

That was a shame, but it was also largely beside the point. Princess Arete was, at long last, a film that Katabuchi could claim as his own work. It was out there in the world, and it was good. As he wrote:

In a sense, Princess Arete may also be an extension of the many personal setbacks I’d experienced. The box-office performance was not as good as expected. However, what was rewarding was that the film was completed in the way I wanted. Many of the other jobs that didn’t come true were, after all, just “plans in my head,” but Princess Arete is different. The film exists […] and it can be shown. If anyone wants to see it, that is.

This is a revised reprint of an article that first ran in our newsletter on March 17, 2022. It was exclusive to paying subscribers then — in honor of Princess Arete’s digital re-release, we’ve made it free to all.

2. Animation news worldwide

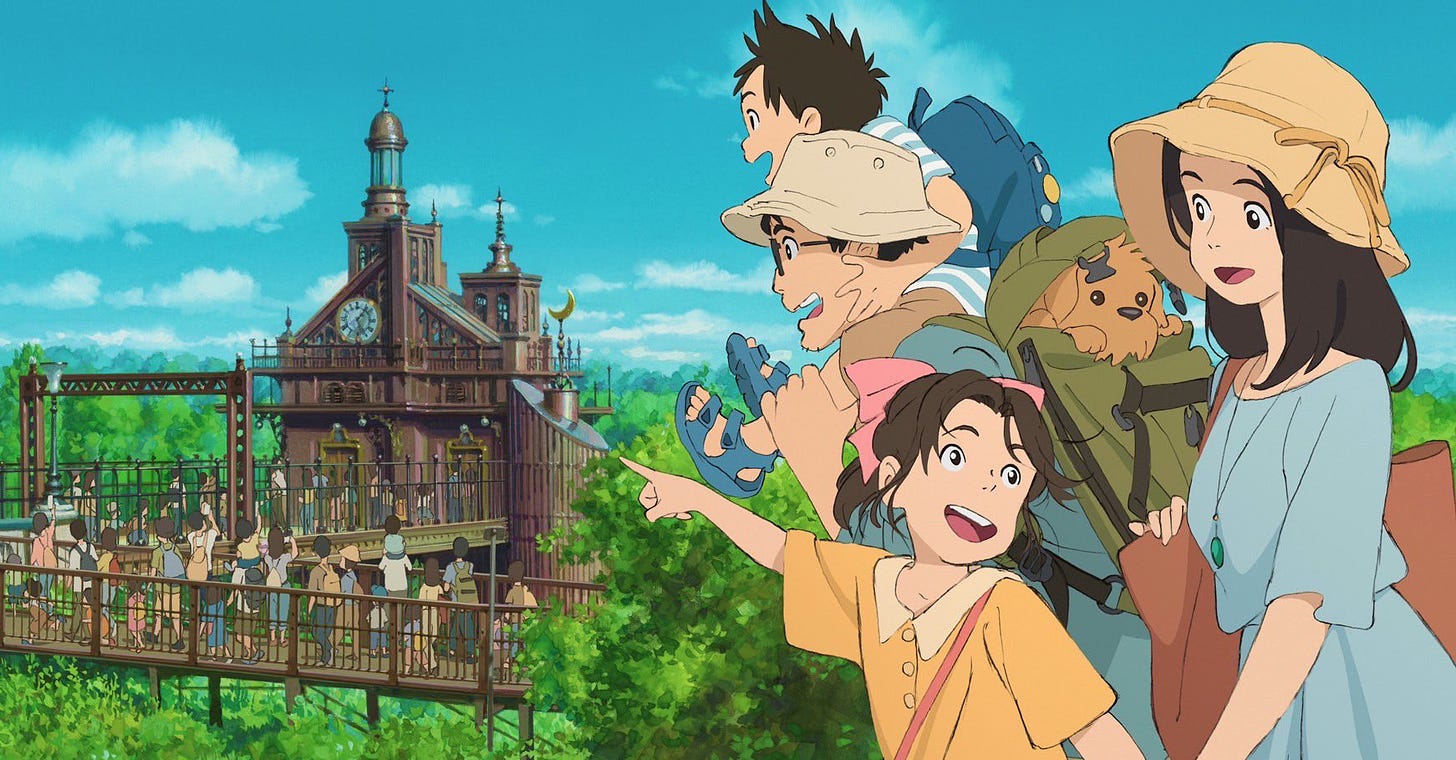

Ghibli Park opens

On November 1, the long-awaited Ghibli Park in Aichi Prefecture opened its doors to the general public. The Asahi Shimbun reported that it occurred at “10:00 a.m. in light rain.” It’s been seven years since the idea for the park came up, and five-and-a-half years since Goro Miyazaki, who spearheaded the entire project, began working on it.

Ghibli Park isn’t what it sounds like. It’s not the Studio Ghibli version of Disneyland. In a quote published by CNN, Goro Miyazaki explained:

People think of it as a theme park, but I’ve always wanted it to be a park. I think that parks are first and foremost for the local people, so I want them to be loved by the people of Aichi more than anyone else. Even if people can’t come right away, I would be happy if they could take a peek at the entrance and visit the exhibition.

At a press event last month, he noted that the team’s “first consideration” was to avoid damaging or overdeveloping Aichi Expo Memorial Park, in which the smaller Ghibli Park resides. Tree cutting was kept to a minimum — whenever possible, trees were transplanted rather than destroyed. The project sourced as many building materials as it could from Aichi itself, he said.

The location was a natural fit. Aichi Expo Park is the site of the former Expo 2005 — a huge, global event. Back then, Goro Miyazaki supervised the construction of “Satsuki and Mei’s House” (a replica of the home from My Neighbor Totoro) as a special attraction. It’s been open, and popular, ever since. Ghibli Park has sprung up around it.

According to Goro Miyazaki, most of Ghibli Park was designed to be touched. “This way, the objects come alive,” he said. The point is for visitors, and especially young children, to be immersed in these worlds. When the respected anime historian Seiji Kanoh previewed the park on October 31, he compared the experience to “visiting castles and old houses” — not theme parks.

This immersion has a point of its own. Goro Miyazaki said that one of his main incentives to build the park was the retirement of his father, Hayao Miyazaki. It was a way to “preserve [Ghibli] for future generations.” When his father un-retired, Goro Miyazaki joked that it was like having the ladder pulled out from under him.

Speaking of Hayao Miyazaki, he and Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki visited the park privately, by themselves, before it opened. The older Miyazaki was very positive — calling it omoshiroi (interesting, fun, amusing) and saying that it had ideas he wouldn’t have imagined himself. There was a sense of rivalry to his words, according to Suzuki.

The idea is for Ghibli Park to persist long after the hype of opening day cools off — just as a nice place to visit, even daily. On November 5, the start of the park’s first weekend, it was “crowded with many families and other visitors,” reported Fuji News Network. But chaos was at a minimum.

“Although there were concerns about traffic congestion on the roads around Ghibli Park,” the outlet noted, “there was no significant congestion in the morning or afternoon.”

Newsbits

On the subject of Ghibli news from Japan, the theme song for Hayao Miyazaki’s How Do You Live? has been recorded, although details about it remain scarce.

Also in Japan, the winners were revealed at the amazingly named “New Chitose Airport International Animation Festival.” The grand prize for shorts went to Backflip by Nikita Diakur (with sound by David Kamp). Barber Westchester won a Special Jury Award that raved, “The most important discovery of the decade.”

At a French event, Utopiales 2022, the anime legend Rintaro showed off pages from his forthcoming autobiographical manga.

American animator Ian Worthington hints that a new episode of his series Bigtop Burger will arrive in the coming week.

Japanese director Hiromasa Yonebayashi (Arrietty, Mary and the Witch’s Flower) collided with a car on his bicycle, broke his knee and requires surgery. He tweeted Saturday that he was already drawing on a digital tablet in the hospital.

Big news for fans of American animator Bobe Cannon: a lost pilot film he animated in the early ‘60s has been found and released in great quality.

Lastly, we explored the realism of Run, Melos! — an overlooked anime classic with an all-star team, including Satoshi Kon, Toshiyuki Inoue and the art director of Kiki’s Delivery Service, Hiroshi Ōno.

See you again soon!

From one of Katabuchi’s many columns for Anime Style. He went into unbelievable detail about his career in well over 100 articles. Alongside the ones linked in the main text body, we also used columns numbered 7, 19, 25, 34, 51, 56, 57, 60, 61, 65, 96–101, 104–106, 108, 110–112 and 133.

From Turning Point 1997–2008 (“You Cannot Depict the Wild Without Showing Its Brutality and Cruelty”). Miyazaki made this point specifically in a discussion about background art.

Thank you for these valuable informations! I really wondered at the power of its unusual pace, the european cinema's influence makes a lot of sense. And I appreciate the way Katabuchi's personal experience echoes with Arete's. In that last scene with the Golden Eagle, it looks like that he himself was there, through Arete, to finish paying homage to something transcendental but substantial. "The film exists […] and it can be shown." It's very touching.

May I ask if I could have your permission to translate and repost this article on a Chinese anime forum? It's 100% non-profit, and I will put your name and website at the very front. Oh and thank you for your attentive writings on Busifan's works, too. I only learnt about his early films from you. They are very interesting and get me reconsidering today's Chinese anime. Anyways, thanks in advance for your consideration, and please let me know your decision <3

I saw Princess Arete last year after the animator Dong Chang made a youtube video about it (alongside Metropolis and Maquia). I loved it, a really subtle and moving film that has way more to it than I'd assumed from the premise, and I didn't know it had such a story behind it, that's so cool.

Now you point it out, it really does feel like a European animated film in its pacing and tone. Which is kinda interesting as a premonition of things to come, right? 4°C now has a strong following in Europe on sites like Catsuka, and that they'd go on to collaborate with European studios on films like MFKZ and Birdboy: The Forgotten Children...

The humble origins of 4°C are kinda surprising - it reminds me a little of KyoAni's tale of growing out of 'housewives painting animation cels', and makes me see films from that period in a new light. Kôji Morimoto was already a great animator who'd done amazing work on Robot Carnival, but that definitely doesn't pay well... I've got no idea what sort of resources it takes to launch a studio. I wonder what sort of computers they were using to composite on in this period...

Thank for writing in such depth about this film! AniObsessive is such a treasure.