Welcome! Glad you could join us. It’s a new weekend, and that means a new edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s what we’re doing this time:

One — the chaotic tale of Destino, Disney’s surreal crossover with Dalí.

Two — animation news from around the world.

Three — a trove of classic Armenian animation.

Four — the retro ad of the week.

Five — the last word.

Before we get into it — don’t forget to sign up, if you haven’t already! It’s free and it only takes a second. Catch our newsletter every Sunday, right from your inbox:

With that out of the way, here we go!

1. “What the hell’s all this baseball?”

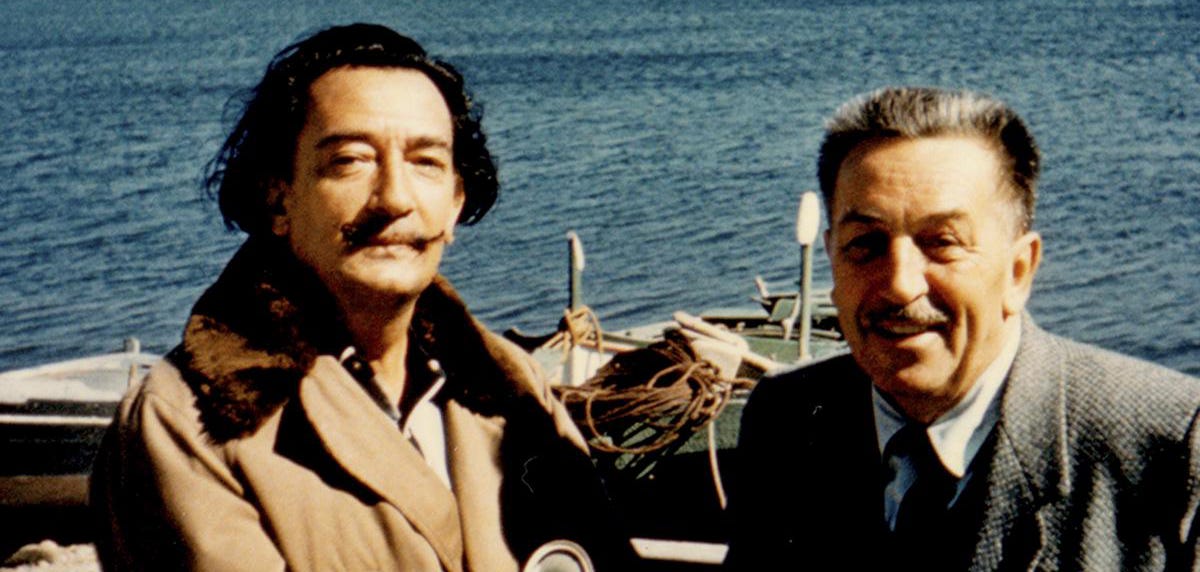

What do Walt Disney and Salvador Dalí have in common? Not much — at first glance. One was the star of surrealist painting. The other was a conservative businessman whose films borrowed very little from modern art. But both were showmen, and both had a keen feel for public opinion. They got along surprisingly well.

And so, in 1945, they decided to do a short film together. The idea thrilled Dalí. His vanity journal, Dalí News, promised that “American admirers of the melting watches can be reassured. These will appear in the film and, thanks to the virtuosity of Disney and for the first time, one will be able to see how they move.” It would all be set to an Armando Dominguez song, originally meant for a sequel to Disney’s Three Caballeros.

As Dalí probably expected, the whole thing fascinated the American press. When news of the collaboration broke, one journalist wrote that Disney had “gone long-hair in a big way.” To him, the project sounded “like Sigmund Freud on a lost weekend.”

Yet the film in question, Destino, would only be finished years after both Dalí and Disney had died. And the form it took, while intriguing (as seen below), was quite different from what Dalí had in mind.

Some of this history was hashed out back in the early 2000s — when Disney completed Destino. Its reasons were partly pragmatic. As NPR reported, Roy E. Disney learned that the company didn’t actually own the sketches and paintings that Dalí had done at the studio in the 1940s. But it could own them, the contract stipulated, if Disney just made the film. Here’s how he put it:

I went back to the attorneys and said, “Well, if that's true, does it mean that, if I finish the film, we would own it?” Because we know that there’s some millions of dollars worth of artwork that’s unavailable not only to us but to anybody.

And, after some deliberation, they came back to me and said, “If you make every honest effort to make the film that they intended to make, and not just use the art in some other context, then yes, indeed, we will own it.” And I thought, “Well, that’s creating value for the company, as long as I don’t spend too much money making the movie.” It’s only six minutes long — what can it cost?

That’s where things get interesting. We know now, thanks to the work of scholar and conservator Ron Barbagallo, that Dalí intended a different Destino than Disney made.1 In fact, Destino probably wasn’t even going to be a six-minute film — even though Walt Disney had wanted it that way in the 1940s.

It all goes back to the storyboard. When Dalí began working at Disney’s studio in 1946, he was partnered with John Hench, an experienced story artist. Hench’s job was to help Dalí navigate the motion picture medium. Beyond that, Disney gave Dalí an incredible amount of freedom. “Walt was kind of entranced by the whole thing,” Hench recalled. He just let Dalí work. And work he did — in his feverish, prolific way.

The story sketches that Dalí and Hench produced were wild — too wild to become a film at Disney in the ‘40s. Barbagallo wrote that “almost everything in every frame was meant to animate, and animate at different percentages of visibility.” The sketches draw from a range of references, from Dalí paintings to Disney films and beyond. No animated film had ever looked like it.

Key to the whole thing was morphing, some of which survives in the finished Destino. Dalí consistently wanted to show one image being born out of another. A good example is the only sequence shot during Dalí’s stint on the film — the one where two large heads meet to form a ballerina.

As Barbagallo notes, the storyboard grew far beyond the planned six minutes. One important moment was an ambitious “baseball ballet” sequence near the end, mostly absent from the finished film. “About the game I know nothing,” Dalí said during production. “But as an artist I am obsessed.” According to one person at Disney, this obsession caused problems:

I went down there, and Walt was raising hell. He said, “Take a look.” All the beautiful, moody drawings of the girl were gone, and the place was covered with the most beautiful drawings of baseball players.

After a while, Dalí arrived. “What the hell’s all this baseball?” Disney demanded.

In the end, Dalí’s sweeping ambition collided with Disney’s practicality.2 Barbagallo relates a story from Bill Melendez (A Charlie Brown Christmas), who recalled the moment in July 1946 when Dalí finally quit. Disney was demanding more and more cuts. Fed up, Dalí stood and said, “I can’t work on this. The paper is pre-designed.” Then he left.

Over the years, time and theft chipped away at the storyboards that Hench and Dalí had made. When it came time to finish Destino in the early 2000s, the team struggled to understand what the sketches meant. They seemed almost random, without a coherent story. The art became inspiration rather than blueprint — director Dominique Monféry re-boarded the film.

Then, in 2014, the original storyboards turned up. Barbagallo received a collection of digital image files — “72 story sketches and 13 sheets of photographs of storyboards,” to be exact. The sender asked Barbagallo’s opinion, as a conservator who’d worked for Disney, about what they might be. After studying them, Barbagallo determined that they were Hench and Dalí’s work. Some of it wasn’t even in Disney’s collection.

Barbagallo compiled the images one by one into an animatic. (See part of it here.) Far from an incoherent swirl, the storyboards revealed themselves to be remarkably tight when placed in the correct order. They break sequences down beat by beat. And the story they tell has a clear emotional arc — centered on the male protagonist and his endless quest for love.

“The film was never meant to be odd or harsh — conversely, it’s romantic, almost a baroque ballet of imagery,” Barbagallo has argued. “It’s actually quite literal.”

You could still call Destino as Disney finished it “a baroque ballet of imagery.” Yet, if Barbagallo’s reconstructed animatic is anywhere close to accurate, Dalí’s full vision was richer and more complete than anyone guessed. But maybe it shouldn’t be too surprising that something Dalí made was more sane than it first seemed.

“The only difference between crazy people and Dalí,” he famously liked to say, “is Dalí is not crazy.”

2. Headlines around the world

Virtual animation festivals at home and abroad

Even as the COVID-19 pandemic winds down, the trend of virtual film festivals persists. We’re watching out for two on the horizon — one in San Francisco and one in Canada.

First, we have the Bay Area International Children’s Film Fest. Its lineup this year is exciting — a few highlights include talks by Pixar alumni Enrico Casarosa (Luca), Madeline Sharafian (Burrow), Mike Jones and Trevor Jimenez (Soul). The hyped Mum Is Pouring Rain will be there as well, alongside many more films. BAICFF runs from July 22–25, so we’ll be writing more about it next week.

A little further away, there’s the venerable Ottawa International Animation Festival in September. It revealed its selections this week — and it’s a diverse bunch. We’re looking forward to A Bite of Bone, especially. It’s a trippy-looking short directed by Honami Yano and produced by the master animator Kōji Yamamura. (Check out the trailer.)

BUSINESS: The financial reality of feature animation in China

In China, animation is booming. The country’s appetite for the medium seems insatiable — it’s one of Japan’s top-two anime importers. Meanwhile, China has gobbled up Japanese talent and tech, and has started to produce its own anime at a rapid pace. Blockbusters like Ne Zha see box-office returns to rival Pixar and Disney.

Nevertheless, as the head of the Chinese streamer Bilibili said last year, most China-made animation doesn’t break even.

On Monday, this concern reappeared in a Chinese-language article shared by The Paper. Right now, a production house called Original Force is going public. The move comes a few years after its original feature film, Duck Duck Goose, flopped in 2018. That project devastated the studio and forced it out of the original-content race. The article points out that this isn’t exactly uncommon.

Chinese feature animation is kind of an all-or-nothing game. Clearly, the country can make runaway hits like Ne Zha and Jiang Ziya. But they’re among the only animated features to break the billion-yuan mark (roughly $154 million). A handful, like Boonie Bears: Blast Into the Past, top 500 million yuan. Many fall below 100 million yuan, or around $15.4 million. And original IP tends to sink to the bottom.

See the original film Realm of Terracotta. It’s the first animated feature of 2021 in China’s crucial summer season — and it underperformed just this week.

Still, despite these market realities, there’s a desire to force Chinese animation forward. The head of Bilibili clarified last year that his company would continue to invest in domestic animation, even though most of it loses money. And, as an article pointed out last year, government subsidies are propping up the industry. If these trends hold, even commercial disaster may not slow China.

Best of the rest

The Daytime Emmy winners were revealed on Saturday. Among them are Hilda, Animaniacs and Elena of Avalor. There’s also a voice-over win for Parker Simmons, creator of Mao Mao. “I’m going to cry and throw up now,” he wrote on Twitter.

Meanwhile, the Primetime Emmy nominees were announced on Tuesday. Robert Valley’s stunning Ice is up for “Outstanding Short Form Animated Program.”

Barber Westchester, the new feature film by indie animator Jonni Phillips, is on track for a Patreon release in November. (See Phillips’ one-of-a-kind style in the film’s trailer.)

Japan’s Ghibli Museum has been hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. To survive, it started a crowdfunding campaign on July 15 — which blew past its goal in less than 24 hours.

Studio Ponoc has made an eight-minute film, Tomorrow’s Leaves, for the Olympics. Directed by Ghibli’s Yoshiyuki Momose, it’s set to stream on July 23.

This week, news broke that Cartoon Network had picked up Chaz Bottoms’ Battu as a series. Matthew A. Cherry (Hair Love) is attached. Our interest is piqued.

A new special, Akissi, will adapt the French-Ivorian children’s comic of the same name. It’s a French cartoon, but a few studios in Africa are involved. Akissi will debut in France in late 2021 and on Boomerang Africa next year.

The Duchess of Sussex, Meghan Markle, is doing a children’s cartoon for Netflix. Once again, the animation gold rush is spreading the medium in surprising ways.

3. Treasure trove — Armenian animation

When you think of animation hotspots, the small nation of Armenia doesn’t exactly spring to mind. And yet, as a member of the Eastern Bloc in the 20th century, Armenia punched way above its weight class. An Armenian directed Russia’s The Snow Queen, Hayao Miyazaki’s favorite film. Then there’s Robert Sahakyants — one of the USSR’s true originals. Right now, you’ll find these gems and more hidden away on YouTube.

First, Sahakyants. Even if you don’t know him by name, you may know his surreal, ever-shifting comedy Wow, a Talking Fish! from the 1980s. That’s only the start, though. Many more Sahakyants classics are available on his studio’s YouTube channel, which his family started after his death in 2009. Catch bizarro wonders like In the Blue Sea, in the White Foam, Wow, Butter Week! and The Fox’s Book — all with English subtitles.

But Sahakyants isn’t Armenia’s only visionary animator, despite being its most famous. That’s clear when you visit the YouTube channel for the National Cinema Center of Armenia. You can lose yourself in here — Magical Lavash, Aida Sahakyan’s Lamp and Elvira Avakiyan’s Jug of Gold are just a few of the beautiful cartoons on offer. These may not have subtitles, but their visual imagination is still something to behold.

4. Retro ad of the week

What kind of TV commercial matches the creative range of idents? Also called station identification, these are the little ads that tell you what channel you’re watching. They’ve been a legal requirement in America since the early days of TV — a formality that artists have flipped into things like the iconic, white-on-black Adult Swim spots.

This week, we’re taking a look at a retro ident by Faith and John Hubley. It’s called All in the Game, and it’s extremely ambitious — and nearly three minutes long. That’s because the Hubleys made it for a special purpose. It aired in September 1962 as the premiere broadcast by WNDT, the first educational channel in New York.

There’s a wild, winding story behind WNDT — today called WNET. PBS did a whole documentary on it. Basically, it wanted to put art and culture on television, and to push the medium in directions it had never gone. (One of its key producers was Joan Ganz Cooney, creator of Sesame Street.) With All in the Game, the Hubleys deliver a mission statement for the TV station that dreamed of fixing TV.

The ad shows two men in front of two screens. One represents the casual TV viewer. The other is a WNDT viewer — and he’s engaged. He takes notes, draws, plays a cello and generally annoys the other guy. It’s funny, and the animation and design by Bill Littlejohn are loose and expressive. He animated straight ahead, per Michael Sporn, and the Hubleys composited his work with their trademark double-exposure trick.

As an entertaining ad for an educational, ad-free channel, All in the Game is something of a paradox. After its premiere, one commentator wrote that it “divertingly conceded that educational TV is not going to be every viewer’s preference.” Still, the Art Directors Club of New York saw the appeal, handing the Hubleys a major prize in ‘63. Even now, the ad holds up remarkably well — and its soundtrack is top tier:

5. Last word

That’s it for this week! Thanks for reading. We’ll be back next Sunday with more animation highlights from around the world.

One last thing. It’s been a while since our last interview, and we’re planning to do more. Right now, we’re compiling a list of folks to hit up in the coming months. This is a good time to let us know if there’s a creator you’d like us to interview! We’ll be rolling out a new, mid-week segment dedicated to our chats before too long. Stay tuned.

Hope to see you again soon!

After we published this piece, Barbagallo was kind enough to contact us with a few extra thoughts and details. He notes that Dalí’s earlier attempts to work in Hollywood set the stage for everything Destino was meant to be:

The backstory of Destino really hinges on how Alfred Hitchcock lured Dalí (who was a big film fan) to Hollywood to work on Spellbound, and how Selznick and Hitchcock also left Dalí to his own devices. That led to Dalí delivering a much longer piece of film than he was asked to make, and Dalí being fired and his sequence ruined (in Dalí’s mind).

You can’t leave that out because that is why Dalí was so willing to salvage his Hollywood adventure by doubling down and making a real effort to work within the framework of a Hollywood system. In many ways, Dalí did adhere to a Disney aesthetic and if this sequence could have been executed in 1946-ish, it would have been very much like “Night On Bald Mountain/Ave Maria.”

In another note from our correspondence with Barbagallo, he argues that Disney’s reason for hiring Dalí came from a practical place from the start:

It was no different than bringing in Kay Nielsen or Oskar Fischinger. It was an attempt to do something grand not only for publicity but to regain the momentum he lost [after World War II and the Disney animators’ strike].

If you interpret Disney’s decision to greenlight Destino this way, it only makes sense that he’d be frustrated by Dalí’s antics. Barbagallo paints it as an uncomfortable clash between the world of business and the world of fine art.

That Salvador Dalí piece was amazing! I'd seen it before somewhere but never knew the backstory. As always thank you—I look forward to these every weekend.