Happy Thursday! This issue of Animation Obsessive is one we’re especially excited to share — a rare dialogue with animator and director Elena Rogova.

Rogova is a huge talent, and her personal short films (like Appearance and Reality) have gone viral online. Our audience on Twitter tends to love her work. Yet, despite the press coverage she’s received, we’ve never come across an interview with her before. We weren’t sure if we could land one ourselves.

Early last month, our teammate Jules reached out to Rogova to see if she’d be open to answering a few questions. It felt like a long shot, but she was kind enough to respond — and to give us very detailed, thoughtful, warm and entertaining answers.

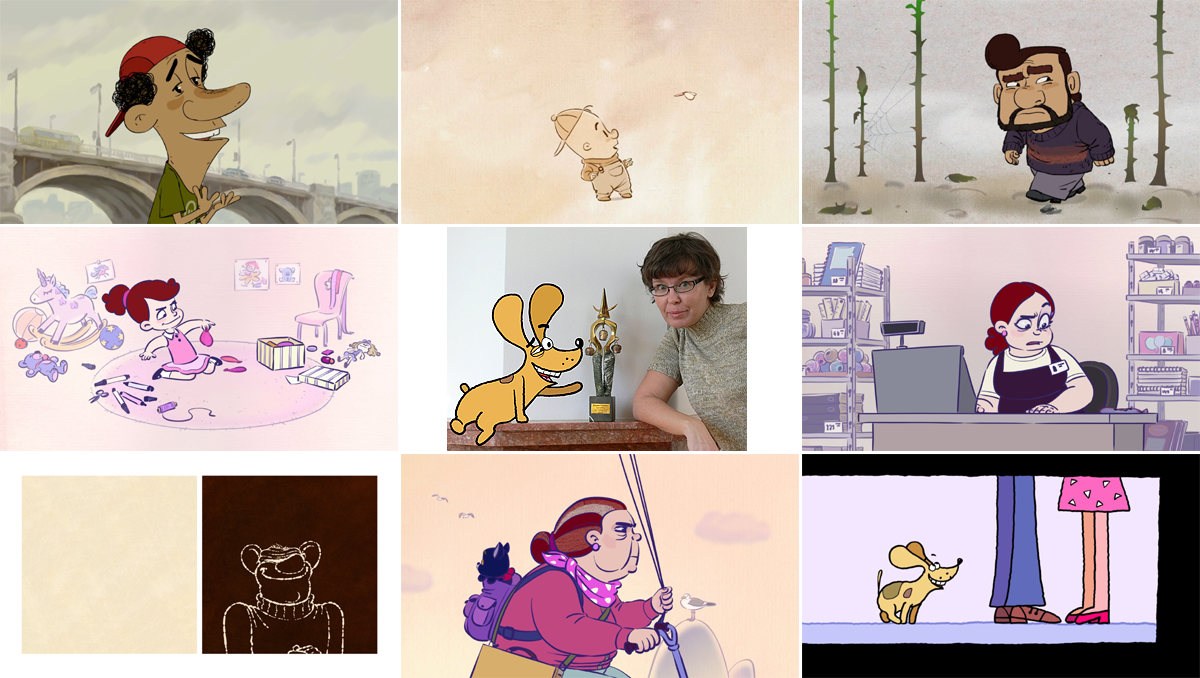

Some of the best 2D animators on the planet are in Europe right now, and Rogova is one of them. Whether in her work for films like Wolfy: The Incredible Secret (2013), or in personal projects like Expectations (2020), Rogova’s skill with motion is clear. But she’s not just an animator, and never has been. Her career stretches back to the ‘90s, to storyboarding and directing on Mike, Lu & Og — and much more.

What follows is a wild trip through Rogova’s life and work, from the USSR to the chaos of ‘90s Russia, and finally to her current home in Hungary. Jules’ exchange with Rogova didn’t take the form of a question-and-answer interview, so this issue won’t, either. It’s more freeform, much like the events it recounts. (Rogova’s words have been edited and formatted a bit for clarity.)

Enjoy!

To start things off, Jules asked Rogova about her background. “I was born and raised in a small town in the Far East of the USSR, where, in addition to a regular school, I went to one of the city Art Schools for four years,” she wrote.

The Far East lies today in the Russian Federation, and it’s not a region understood by most of the world. It’s on the other side of the country from Moscow. Sections of it are closer to China and North Korea — others, to Alaska.

But the art school Rogova mentioned, despite its distance from the main seat of artistic activity in the Soviet capital, prepared her for her career to come. As she wrote:

… the level of education (of classical drawing and painting) at that school was very high — the requirements were clearer and tougher, and more material was given on the history of art and culture, than I later found at the institutes (including the Moscow Institute [smile]). This never ceased to amaze me. So, after that tough school, I could draw and paint reasonably well.

But the story of how an art student from the Soviet Far East became an animator was a winding one — spanning decades. She wasn’t naturally drawn to animating. Born in the 1960s,1 she saw cartoons from a young age but didn’t dream of making them. Even when Rogova graduated from the Moscow State Pedagogical Institute in 1989, she had another career in mind. Life doesn’t always go according to plan, though.

To tell the tale, we turn the floor over to Rogova herself:

Rogova’s origin, in her own words

My path into animation turned out to be rather strange. In fact, I turned down animation three times.

The first time, it happened in childhood — I loved watching hand-drawn animation on TV, but I never thought about how it was done. Once I came across a small book about Soviet animation, where the author, probably in order to show the painstaking work of the animators, placed in the margins a series of pictures of the same little man with a gradually rising hand. It looked so mechanical and monotonous, so boring and dull, that I decided, “Those animators must be crazy to do such a tedious job. It’s not for me. No way.” And I crossed this profession out of my head.

The second time was at the Khabarovsk Pedagogical Institute.2 Out of curiosity, I went to see a demonstration of animated shorts made by students in the elective course in animation, with the thought, “What if I’m missing something interesting?” But then the clumsy cutout animation started playing and I got bored. Again.

For the third time — at the Moscow Institute, the student Nikolai from my group went to the Pilot animation studio and was delighted. Nikolai gave us some colored celluloids with stills from a film (I got a lovely elephant’s butt stuck in the door of a plane). I listened to his admiring speeches, but I already had my own plans for life, so I let it go. I didn’t even remember the name of the studio.

Fast forward some years later (in fact, only three years later, but it feels more like 10 [smile]) — the ‘90s were not easy for anyone. In addition, all my life plans failed, nothing seemed to work, I ended up in Moscow again and then I had a personal disaster (sort of) also. My life began to crumble faster and faster, all its aspects fell apart despite my best efforts. Everything turned out to be futile, everything seemed useless, hopeless and meaningless.

I worked here and there, and, at one of the not-the-best jobs that I managed to find at that time, they suddenly announced that there was no money and in three days everyone was free.

I called a good friend: “I need a job. Quite urgently.”

He called me back later: “Would you work at ‘Pilot’?”

I screamed, “YES!” without thinking.

So, he told me to meet a girl at the subway station who would take me to Pilot. Great!

“But what is ‘Pilot’?” I wondered, hanging up.

It’s funny that, just then, a new casino called “Pilot” opened and the radio played advertisements many times a day. “Is it a casino?!” I thought with a sinking heart. “Well, let’s see how many hours I can hold out.” The fact that “Pilot” turned out to be an animation studio pleased me incredibly.

First, I got into the team of those who painted on celluloid. And I really liked everything.

And, by the way, at the studio I met Nikolai again, who had been working there all this time after graduating from the institute. Why hadn’t I listened to this guy years ago?

Surviving the ‘90s at Pilot

Rogova gave Jules a note in the middle of her writing above. “Pilot was the first private animation studio in the Soviet Union, founded in 1988,” she clarified. “Among the founders — Alexander Tatarsky and Igor Kovalyov.”

It’s hard to overstate the importance of Pilot — or of the founders Rogova named.

Tatarsky and Kovalyov are canonical artists in Soviet and post-Soviet animation. In fact, their influence reached the world. Kovalyov is best known to Americans for his work at Klasky Csupo, as a director on projects like Rugrats and Aaahh!!! Real Monsters. The famous Klasky Csupo visual style owes a debt to the kind of work that Pilot and its founders were doing years beforehand.

Some readers may recognize the Tatarsky-Kovalyov series Investigation Held by Kolobki, begun in the mid-1980s.3 Its characters were later known as the Pilot Brothers, starring in a host of Pilot’s major cartoons. Others may recall Tatarsky’s claymation work for the TV show Good Night, Little Ones! — controversially replaced by Yuri Norstein.

In the middle of Pilot’s peak years of fame, Rogova was there. She joined the studio around 1993 or 1994, just a few years after the USSR collapsed. It was a time of great political and economic instability, as the post-Soviet world picked up the pieces.

When Jules asked Rogova what it was like to work in animation during the ‘90s, she wrote:

I can’t say anything more than “you focus on the task and work as usual” [smile]. And work (for animators) at that time, strange as it sounds, was enough. I think the question would be, “How did people survive in a society during a deep crisis?” And it’s quite a long story.

The main lesson I learned during this time was, “Now, you have to do the same basic things (e.g. eat, work, sleep, keep warm, etc.), but with many more difficulties and obstacles.” I somehow expected that we would all switch to a different mode of life, some kind of special routine of the “Time of Troubles,” but no. This surprised me at the time. But later I suspected that efforts to preserve the basic structure of life (its routine) are precisely what make it possible to return to normal life. Something like that [smile].

Rogova spent a good part of the ‘90s at Pilot. She quickly advanced beyond her early job as a cel painter. “A few months later, Alexander Tatarsky announced a recruitment for animation courses,” she wrote, “and then a strange thing happened.”

Here’s how she explained it to Jules:

Saved by animation, in Rogova’s words

At first, I was indifferent to the news [of the courses]. But, within a few days, without any external reasons, I had a radical transformation — a warm, bright, confident feeling grew in my heart: “This is mine. I’ve come home.” I entered the week with a neutrality toward the profession of animator, and left it beaming with joy and meaning. So, I started to study animation courses.

After that, the remnants of my former broken life crumbled into dust, and a new life began to organize practically by itself. And pretty fast. It was such a striking contrast.

Someone once said something along the lines of, “We live forward and understand our lives by looking back.”

“Saved by Animation” sounds funny, but I owe a lot to animation. It holds a special place in my heart and I’d like to “repay” by bringing something good into it. I hope I did. And will do…

As a storyboard artist at Pilot, I started working on the series Mike, Lu & Og for Cartoon Network. The project was carried out in three places: the USA, Russia and South Korea. It was a bit of a surreal experience — someone on another continent made an animatic out of your drawings, cut and edited a lot, and then in another part of the world someone animated it. The result was sometimes unexpected. But the project was fun and the experience was very useful.

After the second season the series was stopped, I think in 1999 or so, my husband (he also worked at the Pilot studio) and I went to Budapest to work on the animated series Mr. Bean. And since then we have stayed in Hungary.

I can’t list all the projects [I’ve participated in] from memory. On some I worked as a storyboard artist (Bjorn Bear, Horrid Henry, Pettson and Findus, Mamma Moo and the Crow), on others as a layout artist (Mr. Bean, Bosom Pals, Toot & Puddle), on others as an animator (Chico and Rita, Wolfy: The Incredible Secret, Ruben Brandt, Collector, Toldi).

Large projects (feature films, serials) are a team effort. You must be part of a large, hierarchical structure and make decisions only at your level, be responsible only for your part. Sometimes it means you don’t fall in love with the story, or the design, or the director’s vision, but you have to “play as a team,” work with the material that is available.

Sometimes, dissatisfaction with the results of large projects pushes you to start your own, even a small thing. Here you, at least, decide on every aspect.

The personal work

Rogova’s talent has shown for decades. But her time on other people’s projects is only part of her track record — and it’s not the part that’s won her the widest recognition. After years of contributing to films and TV shows that weren’t her own, she started to make personal films independently. And they drew notice.

Per Rogova: “in 2006, my husband and I registered our own small animation company, Amix Film Studio Kft.” It’s the Amix name that you find on her solo work. Rogova’s first short, Listen to Me! (2008), is a funny and imaginative piece about a manic dog — featuring lots and lots of her bouncy, effortless-feeling hand-drawn animation.

Listen to Me! appeared in well over two dozen festivals, winning prizes as it went. And Rogova kept pursuing solo work afterward, on the side. Her personal films remain a side project even now — but they’re essential to her. This is Rogova’s take:

I think it is fundamentally important for a person to have a small piece of reality “in his possession,” which he can manage in the best (in his opinion) way. Whether it’s your own garden, or your own room, where you can finally hang shelves exactly where you need, or your dog, or your hobby — any project. It’s good to take some area of the world under your responsibility, and be an author who loves this project and invests in it. If a person’s life is chaotic, this gives it structure; if dull — meaning. This strengthens the connection with reality. This makes you focus and disconnect from the problems of a large and unstable world. Seeing how this small part of reality works, becomes better and gives results — it brings satisfaction and peace of mind. In general, this is something like a personal anchor, a stable “point in space.” For me, these are my animation projects.

In my own films, I like to do everything myself (in the visual part) — this is the meaning of doing an author’s film for me. This is my piece of reality, where I make decisions. But sometimes I consult with my husband — this is my abbreviated version of co-authorship.

Telling Jules about the animation she admires, Rogova cited a long list. Several are Soviet classics: Yuri Norstein’s Hedgehog in the Fog, Igor Kovalyov’s Hen, His Wife and Fyodor Khitruk’s I Give You a Star, Island and Icarus and the Wise Men. The post-Soviet Once by the Blue Sea (Alexei Kharitidi) turns up as well.

But Rogova’s picks are diverse and international. Among them we find The Monk and the Fish by Michaël Dudok de Wit, The Cat Came Back by Cordell Barker, The Village by Mark Baker, Ersatz by Dušan Vukotić, Sylvain Chomet’s The Old Lady and the Pigeons and more.

“As a viewer, I am more interested in animated films with meaning,” wrote Rogova. “Especially if the meaning is in showing a pattern of reality. Especially if this pattern is seen by the author in a new, fresh and interesting way.”

That colors her own approach as a filmmaker — which has resonated with a lot of people around the world. Her second personal short, Appearance and Reality (2014, above), didn’t take long to go viral, ultimately gaining more than a million views on Vimeo. It went viral again when we shared it on Twitter this September, picking up another half-million views.

Its creativity speaks for itself: Appearance and Reality is a film about feelings hidden and feelings shown, played out in split screen, all through Rogova’s masterful drawings.

Her 2020 film Expectations (see it here), about how life doesn’t match our plans, deserves similar praise. And it struck home for a lot of people, once again, when we shared it on Twitter last year.

To close out today’s issue, we’ll hand the mic to Rogova one more time. This is how she described her filmmaking process:

Rogova’s technique, in her words

As an author, I’m interested in stories about parts of reality, about life patterns, that can be expressed in pantomime.

It’s interesting to do something with a universal, philosophical bent, but I don’t really want to go into the “sign” style, where the characters are simplified to a symbol (a circle with dotted eyes and sticky hands). That lets you more easily express philosophical concepts, but I want to preserve the concreteness and individuality of the characters, the beauty of their movements, their psychology and the backgrounds of the world in which they live. So I try to combine abstract space and real (everyday) space.

With Appearance and Reality — I knew that it would be difficult for the viewer to see parallel events on two screens, but I really wanted to try to see if it was possible (for me) to do this. The story is therefore reduced to the simplest — the two meet and, after talking, go their own way. For balance: a child, a puppy, a butterfly, for which the internal sensations and the manifestation of these sensations coincide. And there is no particular morality here; it’s just a slice of life.4

Also, I gave myself the special task of tracking the opposite directions of mood: for the character in jeans, his mood outwardly improves, but on the top screen his mood worsens; for the hero in a cap — on the contrary, it goes down from joyful to sympathetic-sad, but on the top screen it goes up, from annoyed to joyful. It was interesting to work with such a task.

About Expectations:

As a child, the heroine dreams, “I’ll grow up, I’ll be a beauty, a smart girl, and I will have everything — glory, a prince on a white horse, a great family…” Then life covers her sky with a dark cloud, and in bad weather some dreams will be blown away, others will burst, others will deflate.

Suddenly, a middle-aged person wakes up — where am I? The family did not happen, the work is banal, I myself am not a picture from the cover [of a magazine] and it turns out that I have no hopes or expectations left. The heroine, after a mental crisis, pulls herself together and finds other dreams for herself, simpler than in childhood: getting a cat, riding a bicycle, starting to draw, traveling.

Some of her plans came true, some did not, but she kept the unfulfilled in her hand until old age. Then, finally, she looked at them and let go. A revision of life plans is always a little sad, but now your hands are free. Maybe it’s not worth it, stubbornly, to achieve each goal, to hold on to them endlessly…

And, by the way, when you (in your 40s or 50s) suddenly stop and realize: “That’s it! I know for sure! I will never have: A) a yacht, B) a villa in Hawaii, C) a Nobel Prize and Oscar, etc.” — it surprisingly makes you feel better and freer. It’s nice to know at least something for sure in this unstable world [smile].

I’m doing another “short story” right now, but I have no idea when I’ll be able to finish it. Working on your own short films while working on someone’s big (or not so big) projects is always a challenge. All I can say is that it’s always going slowly, sometimes very slowly. It seems like you just have to accept it and just keep working. Which is what I’m doing…

We’d like to thank Rogova for taking the time to chat with us. As it turned out, she was near a major deadline when we contacted her, but she still carved out a space in her schedule for this. We’re very grateful.

Check out Rogova’s Vimeo and YouTube pages for more of her amazing animation. We’re looking forward to the next personal film — however long it takes.

See you again soon!

The Khabarovsk Pedagogical Institute is today known as the Far Eastern State University of Humanities, located in Khabarovsk Krai.

Tatarsky and Kovalyov originally made the Kolobki cartoons at a state-owned studio, before Pilot began.

Rogova left this note on her remark about the moral of Appearance and Reality: “True, for me personally, the character in jeans is a kind of ideal, since, unlike me, he knows how to control his face [smile].”

Wow what a gem. Appearance and Reality inspired the shit out of me. Holy smokes.