Selling 'Ghost in the Shell'

Plus: animation news.

Welcome! We’re back with a new Sunday issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Our lineup goes like this:

1) When Ghost in the Shell (1995) became a hit.

2) The news in animation.

Now, here we go!

1 – The anime business

Anime is unavoidable today. It’s “bigger than the NFL” for Gen Z, claims Polygon. Many of the top animated shows and movies each year are Japanese, and even Disney keeps losing at the global box office to films like Suzume, The First Slam Dunk, Mugen Train and The Boy and the Heron.

But it wasn’t always this way. Once, Japanese animation was counterculture outside Japan — important, but niche.

America and Europe saw their first major “anime boom” during the ‘90s. Anime spread mainly on videocassette back then, and its fans were rabid. In 1994, a Welsh newspaper called anime “the biggest cult in video for many years.”1

Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira (1988) was a breakout in this era. It became so popular outside Japan in the early ‘90s that the anime industry took notice. “After Akira, we have been considering the world market during the development phase,” Otomo said about his follow-up project Memories (1995).

It was clear to the Japanese business world that there was money to be made here. Bandai’s Shigeru Watanabe, an Akira producer, watched the film blow up stateside and decided to double down on the “trends” behind Akira’s success worldwide. For him, that meant doubling down on realistic animation, which was already rising in anime.2

But Akira had been an accident, and crafting an overseas hit on purpose wasn’t easy. Watanabe was a producer on Memories — which became a flop. There was a knowledge gap when it came to selling anime abroad, he told the Los Angeles Times. Bandai needed the right project, and the right partners. “I don’t think it would work if we Japanese try to make a [foreign distribution] system by ourselves,” he said.

According to Watanabe, his first conscious attempt to capitalize on the realism trend was Ghost in the Shell (1995). And, to make it happen, he worked with producers abroad.

Everyone knows Ghost in the Shell now. It was a film that helped to define the ‘90s — endlessly ripped off, referenced and remixed. This project gave anime an inroad into markets beyond Japan. As scholar Brian Ruh wrote in the 2000s:

… it garnered more attention in the Western media than any previous anime film, save perhaps Akira. … For better or worse it has become an ambassador abroad for Japanese animated film.3

Which wasn’t a fluke. It took time and focus to build up to a hit like Ghost in the Shell.

That story started in the early ‘90s, in London. A local businessman saw Akira at an art film screening. His name was Laurence Guinness — and he was hooked.

Guinness’s employer, Island World Communications, released Akira on video in 1991. It became a UK success that tapped into the growing anime fandom. “We found a whole underground of interested British kids,” said a higher-up from Island, “a cult thing that none of us really knew much about.”4

A few years later, a subdivision called Manga Entertainment formed in London, with Guinness as a key figure. Its business: finding, translating and selling anime with UK appeal. This started to bring in real money, and the company opened an American branch in 1994.

From the beginning, they had plans to get involved in anime production. That was how Andy Frain (then the head of Manga Entertainment) remembered it. He’d been part of the push to license and sell Akira in the early ‘90s. As he said:

... Akira was just amazing and I wanted to release mostly action-oriented, hi-octane science fiction and fantasy titles. So whilst in Japan I picked up what I thought were the best titles around the time. ... It became clear early on in my trips to Japan that the animation boom was over; nobody was prepared to commit Akira level budgets to productions anymore. I’m not saying that more money makes great anime, but with budget limitations — especially in animation — there’s no possible way you can ever produce a film that’s technically as competent as Akira, even with great people. So the idea for co-productions was there from the start, provided we were able to achieve a certain level of success to enable us to invest that sort of money overseas.5

The company was quickly reaching that level. It was one of several in Europe and America finding success with anime.

Their niche was the cool stuff, the flashy, transgressive animation. Mainstream anime like Sazae-san was largely filtered out in favor of stories more akin to big American comic books. By 1995, Manga Entertainment’s audience was “almost exclusively young men,” reported the Los Angeles Times.

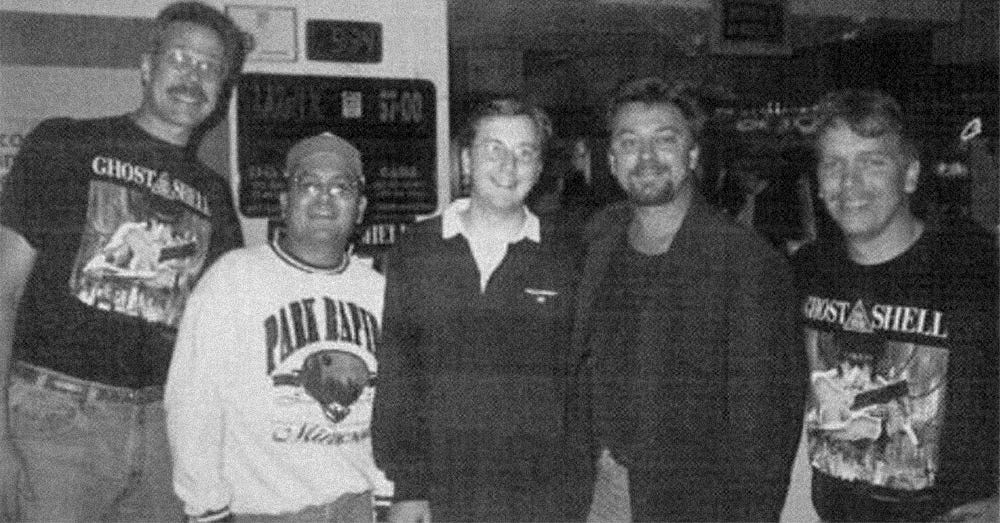

As the company grew in the UK, its American side rose through guerrilla tactics. A former record exec named Marvin Gleicher ran that operation. Most Americans didn’t know what anime was, so he promoted it like music: “city by city,” with an eye toward local businesses and the newspapers in each place. “We set up 150 university animation society screenings for free or for charity. We licensed stuff to MTV,” he said.

Manga Entertainment was doing well in multiple countries — even releasing translations across continental Europe. And Shigeru Watanabe was watching all of it unfold: he had a highly placed colleague at the company.

Watanabe and Bandai started to plan Ghost in the Shell in 1993, and they soon brought Manga Entertainment in as a co-producer. Foreign money and Japanese animators had mingled before: see Sherlock Hound, or DuckTales. But this was different.

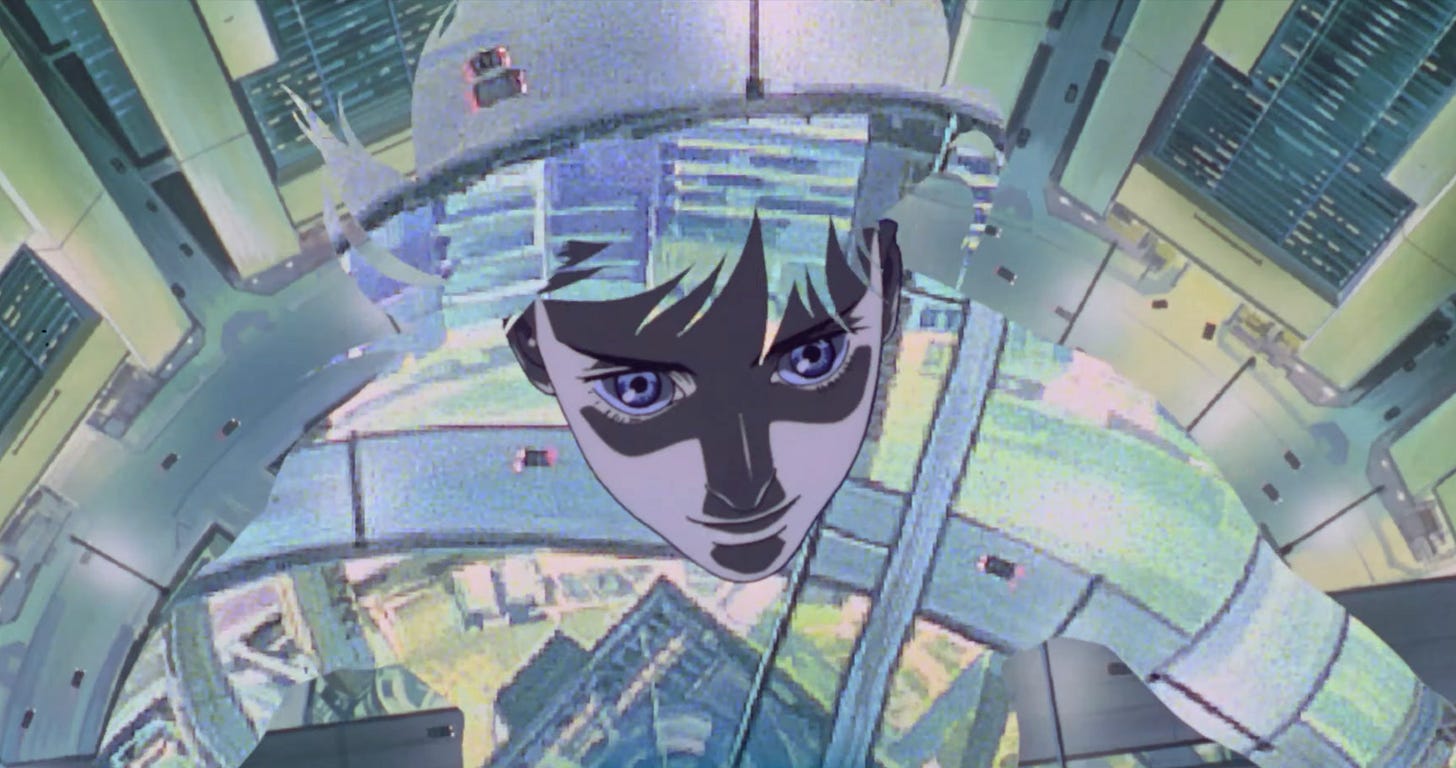

Ghost in the Shell was meant to be a successor to Akira. It was a Japanese feature billed abroad as “anime,” and done in the style that foreigners seemed to like. While Akira’s popularity outside Japan had been an accident, Ghost in the Shell was intended to go big in Japan and abroad. It was a film “aimed at the worldwide market instead of just Japan.”6

Ghost in the Shell looked like a promising vehicle for this plan. As with Akira, it was inspired by Blade Runner. Cyberpunk anime was popular abroad, and so was anime realism. Its story seemed like a good investment to Manga Entertainment, too.

“The appeal was that the storyline was more universal; it appealed more to a Western culture intellect than most [anime] feature films prior to that,” said Marvin Gleicher.

The film’s director, Mamoru Oshii, was an auteur whose work had already gone overseas. He was known for opaque, dialogue-heavy projects. Some in Japan were mortified when he was picked to direct Ghost in the Shell, as his style seemed to clash with the source material, a poppy manga series. Oshii accepted the project from Bandai in part because he needed the money.7

Oshii’s longtime collaborator Kazunori Ito wrote the screenplay. Since Manga Entertainment put up part of the budget (the film cost roughly $3 million), it got to review that screenplay. Like Laurence Guinness explained:

When the script was finally written, I wrote a 25-page script appraisal which contained, as you would expect from twenty-odd pages, a lot of suggestions and comments. This was discussed at length, over many days, with the director. ... Suffice it to say that it changed in small but significant ways so that everybody was happy. We placed a lot of trust and faith in our Japanese partners. Obviously, since we’re based in London, there were physical limitations on how much we could influence the actual production management of the project. We had storyboard approval; we were involved in all the processes up to production, but the actual, physical production was managed by our partners at Production I.G.8

Whatever the edits were, Oshii took them in stride. He treated Ghost in the Shell like any other film. Asked about the concessions made for overseas popularity, he said, “With the characters and story, we are not doing anything different [than usual].”

Really, the biggest concession may have been Ghost in the Shell’s existence in the first place. Investors were interested in a hyperrealistic, Akira-esque action film about themes that attracted foreigners. For that reason, this project got the money to be made. The particulars were left mainly to the team, which included top artists like Hiroyuki Okiura (character designer, animator) and Hiromasa Oguro (art director).

It was a fast production. According to Oshii, it took 10 months — three of them spent just on the complex layout drawings. He called it an “exhausting” job, but he seemed happy enough. Talking after the premiere, Oshii said, “It became more of a straightforward movie than I expected it to, so of all my films, this was surprisingly easier to watch.”9

Ghost in the Shell wasn’t a massive hit in Japanese theaters. There were doubts that it could be a hit anywhere. “It won’t be as big as Akira,” wrote critic Helen McCarthy. She liked the film, but saw it as too alien to “the consciousness of the Western mass media” to catch on. Roger Ebert felt the same way, praising Ghost but calling it “too complex and murky to reach a large audience.”10

Yet it would become a big hit — the biggest of Oshii’s career — when Manga Entertainment released it on video in 1996.

It wasn’t unusual for anime videos to succeed in the West by this point. The fandom had bloomed through local events, clubs, fanzines and the internet’s “hundreds of colorful fan-made home pages” (to quote the Los Angeles Times). The era of the early anime fansite was well underway. Manga Entertainment made a good deal of money with Ninja Scroll (1993), and Fox Video’s release of My Neighbor Totoro had 450,000 tapes in circulation after just 14 months. The successes continued from there.11

Even so, Ghost in the Shell was different.

To begin, Manga got the film a very limited theatrical run in early 1996. Partly thanks to a standout performance in New York, it earned $500,000 ($1 million today). That helped to spread the word and set the video version up for success a few months later.12

You have to combine that, though, with Manga’s years of legwork to build a network of retailers. It sold anime at comic book shops and music outlets, running tie-ins and promo events along the way. One Manga executive said, “We come from the record business and are using music tactics to sell video. We’re promotion maniacs.”13

Some called it a “grassroots” strategy. Manga didn’t have the supermarkets on its side — it had to get creative. Here’s what Gleicher told AWN in 1996:

As mass [market] as we get is Musicland and Best Buy. Music stores now get it — it’s a no-brainer to take a 12-pack of our best rather than pick through 40 or 50 titles puzzling over which to get. Tower has everything. … Rental stores [like Blockbuster] tend to ignore anything that didn’t take in $100 million at the box office. Offer them a surefire Hollywood hit, each branch wants 20 copies. We can only persuade them to take one copy of Ghost. But that copy is always out! Eventually, we’ll educate them.

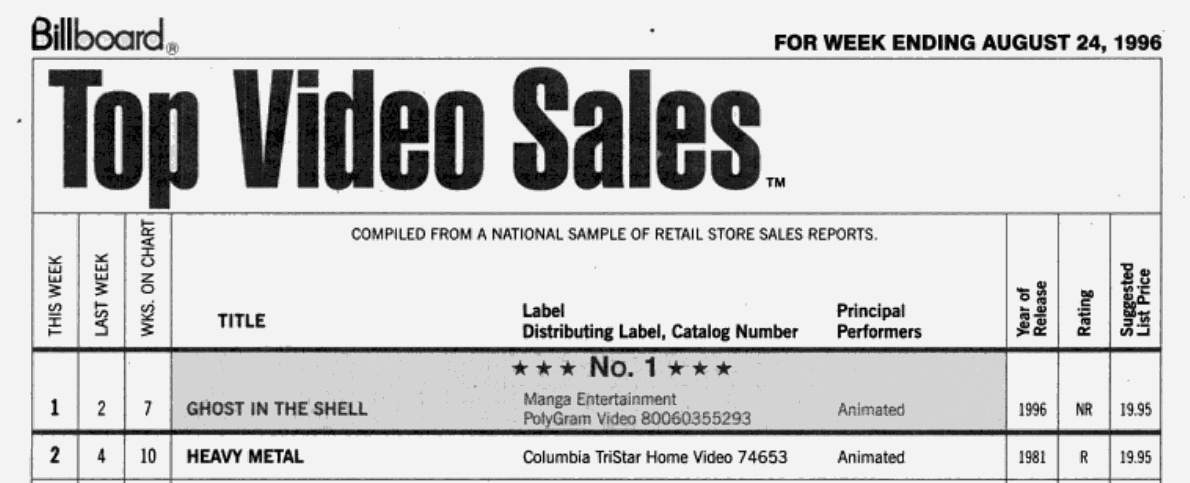

In August 1996, Ghost in the Shell set a record. It hit first place on Billboard’s weekly video sales chart, after placing in the top 40 for nearly two months. No anime film had topped that chart before — Manga had “struck gold,” according to Billboard. After five months, Ghost had sold 200,000 tapes just in America.14

Stores were noticing. “Japanese animation … is moving from the retail periphery to the main aisles,” reported Billboard that October. Ghost in the Shell was cited as proof of “the broadening U.S. market for anime.” It was an auteur film respected by the press — but it was also, crucially, a hit.

Manga Entertainment was happy. Shigeru Watanabe was, too. The gamble on overseas fans had paid off this time: “just that we’re getting a profit is a big deal because that’s never happened before,” he said.

Gleicher put it this way in late 1996:

It has been a groundbreaking year for us, but it has been a long, slow process educating the press and convincing retailers that these films deserve space and attention. I wouldn’t say that Japanese animation has gone mainstream, but it is definitely beyond its former cult status.

From here, Ghost in the Shell kept selling. One report had it over 500,000 tapes by 2001, not counting the DVD edition. That was big money. The kind of money that made the movie business, and the business world in general, pay attention.

At first glance, this is a lot of data and dates — mostly unrelated to Ghost in the Shell’s production. The story of this film is one of artists, visionaries and craftspeople, working hard under a tight deadline. And that story is true.

Still, there’s a second story underneath it. Who paid for Oshii and his crew to make a movie, and why?

Anime is an industry, and industries run on money. Ghost in the Shell was an auteur action film — but it was also a bold attempt by Bandai and Manga Entertainment to grow the Western anime market. And it succeeded.

As a result, Ghost had a tremendous influence. It helped to normalize anime outside Japan. And, as more retailers opened up to anime, it reached more consumers. Which led to more sales. Which led to more anime.

Oshii felt the benefits directly. “It’s much easier to get money for projects now,” he said in 2002. His films only got more difficult and less commercially viable from here, but he got to keep making them. Which hadn’t been guaranteed before.

In the ‘90s, when Bandai pitched Ghost to Oshii, he’d come to the meeting with a pitch of his own. It was a film called Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade. That one ended up getting made after Ghost, and it wasn’t a hit. But Ghost had already secured Oshii’s career.

He looked back on that moment in 2016, speaking at a film festival in Toronto. “Had I made Jin-Roh back then,” he said, “I probably wouldn’t be here today.”

2 – Newsbits

The late Cuban animation legend Juan Padrón, who passed away in 2020, is having his work archived and digitized for public viewing. His daughter Silvia Padrón is behind the effort, collaborating with the German Embassy.

For readers in Hungary, the streaming service Filmio is celebrating the 110th anniversary of Hungarian animation: their catalog is free to watch. (There’s also a large new resource dedicated to the history of animation in Hungary.)

In China, the Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum has worked with historian Fu Guangchao to put together a new exhibition, full of little-seen production art from the history of Chinese animation. There are nice pictures online already.

The new episode of The Amazing Digital Circus, made at Glitch Productions in Australia, is a big hit on YouTube. It’s close to 40 million views after its release on May 3.

In Brazil, the Dublagem Viva campaign has reportedly succeeded in pressuring major companies (including Sony, Hasbro and Toei) to yield to contractual protections for voice actors. It’s a measure to counter the use of AI voices.

In America, The Boy and the Heron will be available via video on demand in June, followed by a physical release in July.

The Chinese hit Deep Sea is now streaming on Peacock.

Check out the new music video by Russian animator Natalia Ryss, a gorgeous piece of collage and abstract expressionism.

Another cool-looking film: The Debutante, recently made available for free on Vimeo. It comes from Elizabeth Hobbs in Britain.

Lastly, we shared a rare book that contains concept art and photos from Jiří Trnka’s film A Midsummer Night’s Dream. You can see the book on the Internet Archive.

See you again soon!

From The Rhondda Leader (July 21, 1994). It’s worth mentioning that Japanese animation wasn’t brand new to the outside world in the ‘90s. As an article in The Observer (December 19, 1993) put it, “Japanese anime or animated features have been around for as long as the Hollywood film industry and have been periodically rediscovered by Western audiences every few decades.”

See this archived page. It comes from a longer interview with Watanabe, collected here.

From Brian Ruh’s book Stray Dog of Anime, an important source today.

From this August 1996 article in AWN, referenced several times. The 1991 release date for Akira’s video version comes from the Paisley Daily Express (November 30, 1991).

From this live Q&A with Oshii — also used several times, including at the end of the article. The worries about his involvement were expressed in the article “Japanimation Splash!” from Kinema Junpo (#1175).

From Cinefantastique (August 1996), one of our major sources here.

From the “Production Report” special feature on the Ghost in the Shell DVD.

McCarthy’s quotes come from AnimeFX (issue 9). Ebert’s are from his review of the film.

For details on Totoro, see Billboard (June 25, 1994) and this article in The New York Times, cited multiple times.

See Boxoffice (September 1997) and The Los Angeles Times.

From Billboard (May 18, 1996).

See three issues of Billboard: October 5, 1996, August 24, 1996, October 26, 1996. Sales figures from the Los Angeles Times. Variety called Manga’s strategy “grassroots.” See Supermarket News for more on the problem of getting anime into major stores.

A lot of memories here. I interned at Manga Entertainment's Chicago office in 1995, right out of college, when they were riding high on the success of GiTS's video sales. One of my tasks was watching screeners of new shows and rating them for potential among American audiences. There wasn't a lot out there at the time, and looking back, it's interesting seeing how their model of curating the next big hit was already outdated. The future lay in an "infinte scroll" of releasing everything the Japanese market was getting in realtime, ala Crunchyroll and other streaming services.

This is absolutely fascinating. As much as I knew about the animation of GitS, I had no idea that the Western distributors were so involved in the production, or that that beloved realist style of Okiura and Inoue was specifically requested to appeal to foreign tastes. (Well played guys, you got this foreigner). Or that Oshii wasn't personally very invested in the manga, I figured it was to his taste! Definitely changes how I look at some of the adaptation decisions. What an incredible gamble though. That's got to go down in the market research hall of fame or something - reading your audience so well that you transform an entire medium.

It occurs to me that some similar call may be happening again now - Chainsaw Man's realist style was not popular in Japan, but Mappa were playing hard for prestige abroad, right? Though perhaps it didn't pay off as well this time...