Happy Sunday! It’s time for a new edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. This is the plan today:

1) An interview with Scot Stafford, composer of Ultraman: Rising.

2) International animation newsbits.

Now, let’s go!

1 – “These Things are Very Rare”

At least so far, 2024 has been rough for animated features.

The trouble isn’t quality so much as quantity. Like Cartoon Brew noted in April, “The major US film studios have released only one new animated feature into theaters through the first four months of 2024.” Things have improved a little since then, but not a lot. Streamers haven’t launched a ton, either. Animated films still do numbers when they do come out, but the industry cuts of recent years have led to a drought.

But there are movies coming up — and Netflix has one to be excited about this month. It’s Ultraman: Rising from director Shannon Tindle (Kubo and the Two Strings), due June 14.

Trailers don’t quite capture this one. Rising surprised us: it’s something deeper, more complex and more emotional than a quippy spectacle film. Plus, it manages to escape the shadow of Spider-Verse — its story and visual style have their own identity.

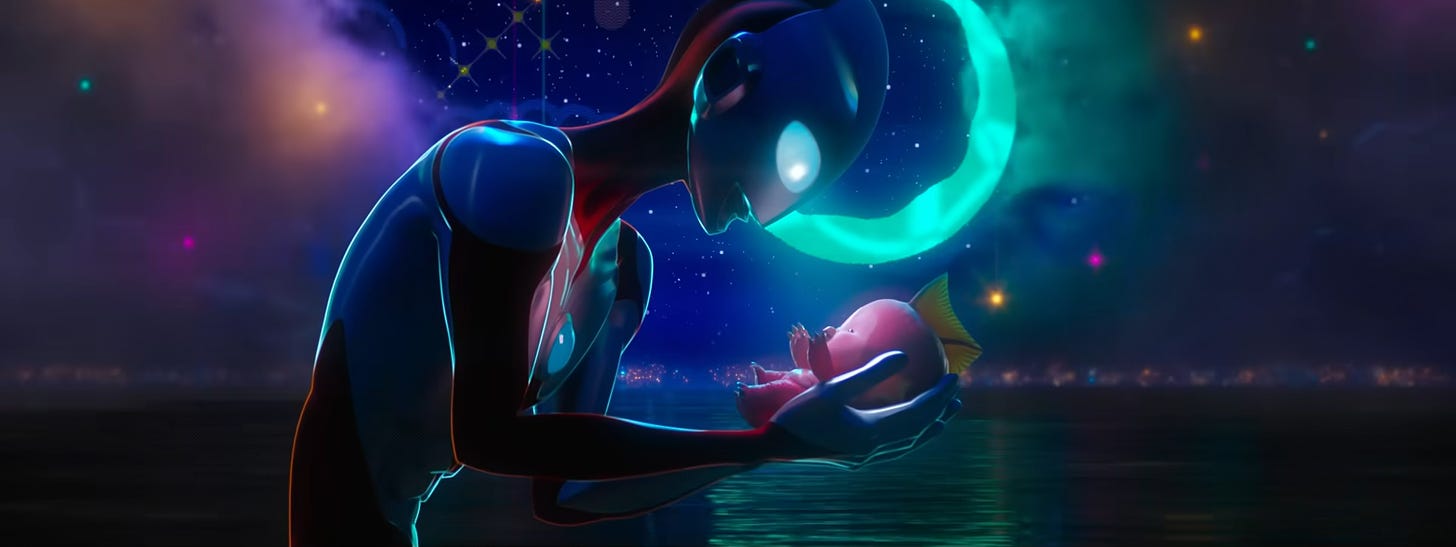

It’s refreshing down to the outline. The lead, Ken Sato, starts as a really awful guy, and the writers aren’t afraid to show it. He’s a star athlete but a smug egotist, with no friends and a strained relationship with his family. Ken is secretly Ultraman, but he hates the job and does it badly. Then events conspire to make him a sort of single dad to Emi, a baby kaiju. Parenthood breaks him down. He has to build back up.

It happens at superhero scale, but the details are all there, and true to life. Rising’s script works on multiple levels and feels thematically whole, interwoven. Combine that with the standout character designs of Keiko Murayama — and the subtle, original acting that the animators pull out of her designs — and it’s easy to get invested in the story.

Also selling that story is the music, which is our topic today.

Our teammate John spoke to Scot Stafford, the composer of Rising. Below, Scot talks about using music and sound for storytelling, working with guitarist Tim Henson of Polyphia, the internal politics of mixing and how Hatsune Miku and the NES ended up in a film score.

Scot’s OST just hit Spotify, so we’ve embedded relevant tracks to illustrate his points. These double as snippet previews for browser and app readers (email readers can click the embeds to go straight to the track pages).

The conversation, edited for length and clarity, follows. As a warning, it includes minor spoilers.

John (Animation Obsessive): How did you get involved with the Ultraman film?

Scot Stafford: Well, I’ve worked with the director and co-writer, Shannon Tindle. We did an animated short called On Ice together, which is the funniest thing I’ve ever seen. Really fun collaboration. And then I worked with him again on a hybrid CG animation, live-action series on Netflix called Lost Ollie, which was an amazing experience.

In terms of how I got involved, I think something that stands out about this project — and about Shannon’s approach and my approach — is that he brought me in back in 2020. Very early in the process. It was a couple weeks before the pandemic hit; we were already talking about our thoughts. He pitched this idea of the score being a hybrid of orchestra and 8-bit sounds from old video game consoles from the late ‘70s and early ‘80s.

We were having these creative conversations early on. It allowed me to try a lot of things, because you have all of that runway to fail and fail again, and then find something that works really well. Being on the job not just as post-production, but actually as part of pre-production, where my ideas could influence animators and visual effects supervisors, and vice versa. We could all be inspiring each other.

It was one of these really special projects that allowed for things like that. It had nothing to do with the budget. It was truly a matter of commitment and creative collaboration.

John: You mentioned the combination of 8-bit sounds and orchestral music. Where did that idea come from?

Scot: That came straight from Shannon. He’s an incredible creative mind and fires off one amazing idea after another, all appropriate and bold. He paints with broad strokes in a way that makes everything fun. Then it falls on me to say, “Okay, that’s an incredible-sounding idea. But how is it actually gonna work?”

In the end, you hear some of the consoles themselves. I have an original Nintendo Entertainment System and an original Commodore 64 that were adapted to be playable like synthesizers.

It was hard because, you know, an orchestra is such an emotional instrument. You can go from the highest highs to the lowest lows. But the second you add in 8-bit sounds, it changes everything. There’s not a whole lot of gravitas or profound emotions, especially when you hear them side by side.

So, what I ended up using the 8-bit for… there are a lot of very funny scenes, and a lot of scenes where things are just not going Ken’s way. When it needed to sound like “pretend superhero” instead of “real superhero,” or things just weren’t going the right way, 8-bit was there to handle that.

John: If I’m not mistaken, there’s some Vocaloid use during a few moments. I’m curious about where that idea came from and what was involved in that.

Scot: I’d been using Vocaloid for other vague ideas at the time, and it was definitely swirling in my brain while I was otherwise trying to find Emi’s musical voice, when Shannon wrote that the Pocket Miku “sounds like what Emi feels like.” Boom. One of many happy serendipities of working with my brother from another mother.

I literally wrote “Emi’s Theme” that day and sent it to him the next. The voice was so cute; the random gibberish it creates from Japanese phonemes somehow sounded so right, and it inspired me to write a musical “round” that sounded like a sweetly innocent and precocious child at a first recital. It triggers a parental pride in me… like, look how quickly she is learning and growing! Definitely funny, too. If something I write makes me laugh, it’s definitely going in, one way or another.

I was really happy at the time that John Aoshima, the co-director, liked it too. He has incredible taste, and as a Japanese-American voice, artist and storyteller, anything I did that brought in that influence, whether traditional or pop, if John actually liked it, I was good.

John: What sequence were you working on where this whole thing started to click for the first time?

Scot: That is a great question. It was called Sequence 1700. That’s a production code — all of the sequences are numerically arranged. But Sequence 1700 covers the death of a very important character and the birth of another. It was the first scene I scored.

I had been working on themes beforehand — themes for the characters and the big concepts, like the concept of family. But you work on these themes in isolation, and you don’t know, “Are they actually gonna work in a real scene?” And then the first scene to look at covers nothing less than life and death. It was also a beautifully pushed, art-forward style. It was quite a challenge.

What was also challenging was that it hadn’t been animated yet. I was scoring to storyboard, which was created by John Aoshima, and it was so beautiful. It was cinematic; it was emotional. There also was very little dialogue. So, I had a ton of flexibility to bring these themes in, and I had to change them profoundly.

Suddenly, this big, bad kaiju theme is supposed to sound really emotional and empathetic and tragic. That was a pretty tough transformation. You have this huge kaiju theme that’s like a roar. How do you make that beautiful, tragic and emotional?

Fortunately, it worked. The music you hear in the final version, which was about three and a half years later, is virtually identical to how it was originally composed. So, thank God it worked.

John: [laughs] Yeah, awesome. So, was this your first experience doing an animated feature score?

Scot: Yes. I’ve done a lot of animated series and shorts, and I’ve done some features. But, in terms of a studio animated feature, it was my first.

John: What were some of the specific challenges of moving to feature compared to the series and the short-form projects you’ve worked on before?

Scot: You know, it’s interesting. My first real animated short was a Pixar-Disney film called Presto, which was released in theaters before WALL-E back in 2008. And every single element of production — pre-production, post-production, everything — went through the exact same flow as a feature. It just had a shorter runtime.

Fortunately, I’ve been able to test drive that workflow. As much as every project and every director [is different] — I’ve worked with well over 20 animation directors by now — there are so many commonalities.

And it’s a very music-friendly format, because it takes a lot of time. You can have a beautifully timed out animatic, and you start to get some animation in. You start to see the concept art. And, especially when you’re working on an animated project where the final image actually looks like the concept art (which is amazing when that happens), you just have time to absorb the project.

Then, once animation is done, there’s still so much that needs to be layered in, with visual effects and color. You actually have time. And I’ve gotten really good at fitting into the animation workflow.

I would say that the only thing different about the feature was the runtime. And that it was a different team at Netflix, who I had a great experience with. So, thankfully, in terms of the format, it was really no different from other projects I’ve worked on.

John: That’s really interesting. So, what is your favorite musical moment that you worked on for this film?

Scot: Well, the death and birth scene is still way up at the top. I mean, there are so many. The amazing thing about Shannon Tindle is, it’s very hard to fit humor and emotional gut punches and action together, one after the other. And he’s just able to do it.

I think people are going to be surprised by how emotional it is. It reminds me — not literally, but in terms of the vibe and the tenor and the feel of the whole piece — of movies like E.T. and Close Encounters. Where you have these really messy depictions of families. It was emotional, it was raw. Homes were literally messy. And it kind of reminded me in a very, very good way about all of those films.

This is kind of stalling to try and figure out my favorite favorite scene.

John: [laughs]

Scot: I think it might be the one that comes immediately after. We’ve seen the death and birth scenes, and then we see Ultraman bring the child home. And I don’t want to ruin any of it, but you go from these really intense, almost sacred emotions, with incredible drama, to something that is just so charming. It is so cute.

To be able to go from one thing to the next really says a lot about the quality of the creative team working on it. And it’s an incredible opportunity for a composer to say, like, “Yeah, I can go from a huge action scene, to a tragic death scene, to an exciting and mysterious birth scene, to adorable slapstick.” I mean, there’s nothing better.

John: For sure. So, I’ve read that you have a tendency to mix music and sound, and I’m wondering how that played in.

Scot: I’ve been a composer since I was a child, but I’ve also gotten into a lot of sound design over the years. Traditionally, music and sound design are done by very different departments, totally different buildings, totally different workflow. And there’s actually a systemic adversarial nature to that relationship between composer and sound design. Because they’re so siloed in these different departments; there’s so little collaboration between the two.

They only come together at the very end, in the final mix. When, frankly, music that is deaf to sound design and sound design that is deaf to music just make a huge mess, and it results in sort of a loudness war. Of course, a great mixer is going to be able to resolve all of that, but it does feel like a bit of a missed opportunity.

So, over the last 16 years or so since Presto — which was really the moment I woke up to all of this — I’ve been doing everything I can to integrate the two processes. In my past work, if you look at my credits, it’s pretty evenly spread between music and sound supervision. Where I pull in amazing sound designers, and I’m able to collaborate with them as their sound supervisor. As a result, I’ve been able to integrate music and sound, so that they’re already speaking the same language when we go to the final mix.

On Ultraman, I had the opportunity to work directly with Randy Thom, who is an absolute legend among sound designers. His first movie was Apocalypse Now, which I think it’s no exaggeration to call the most influential film in the history of cinematic sound design. He’s done many, many dozens of films since and won many, many awards. He did Iron Giant and The Incredibles and a lot of live action as well.

He was also hired very early. And, when we would get a new full-length cut of the film, I would call up Randy and Leff Lefferts, who was the supervising sound editor. Both of them are at Skywalker, which is only a 20 minute drive from my house. And the three of us would sit together — no director, no one from the studio, no producers. Just the three of us watching the film together and talking about ideas, about story. About, “Hey, this could be an opportunity for sound to carry all the weight of the scene, or vice versa.”

Because of that, when we got to the final mix, it was really something special. I’m sure it’s happened before, but these things are very rare.

A lot of people might think a final mix is about turning up the bass, turning up the mid, turning up the treble, making it sound good. It actually has nothing to do with that. It is a storytelling process — where we were able to sometimes advocate. In my case, I would have the sound turned up and the music turned off. Likewise, Randy had sound entirely removed from one scene, so that it’s only music. Which was quite surprising.

We just had a pretty genuinely collaborative approach that I think you can hear. You can hear that the sound and the music are listening to each other.

John: Love that — that’s a great answer. So, this is sort of a wrapping-up question, but I’m curious what your favorite story is from working on the project.

Scot: Oh, gosh. Let’s see.

So, I had the opportunity to work with Tim Henson, who’s one of the twin lead-guitar gods of the band Polyphia. They’ve kind of dominated YouTube and social media for the last few years. This guy is a bit of a rockstar. It might sound like an exaggeration, but it almost seems like what Eddie Van Halen did to guitar playing in the ‘80s.

I never would have thought of adding electric guitar to this soundtrack. But, when I heard him play, he makes it sound like a modern instrument.

The way he plays it is just unlike how people used to play it. There’s a lot of pitch harmonics — and, basically, his whole process is that he shreds and then uses Ableton Live, where you can edit everything into a completely different composition. Then he has to say, “Okay, how am I going to play this? Because I originally played it, but then I chopped it up until it was totally amazing, weird and insane. How do I actually play it?” It’s a really interesting creative process.

I would bring him into some of the scenes where it was the opposite of the 8-bit sound. He was for when you really needed the sound of a superhero. That is something that the electric guitar can do — there’s something superheroic [about it]. And the way he plays is so virtuosic, it just sounded perfect.

He was so easy to work with; he was so fun. I wish I could just give you a transcript of some of the conversations we’d have over dinner, with a drink or three behind us. You can just listen to this guy riff on life, aliens, conspiracy theories and music for hours. I would say that was a really great highlight of the project.

And I’ll tell you one story that just harkens back to what I was talking about, the final mix.

Ken turns into Ultraman, but as a human he’s a superstar baseball player. There’s a scene where everything has been going badly: he’s been losing, he’s been a mess. And he’s having a moment after a game in which he completely fell apart. You hear the murmuring of an athletic sports team’s locker room after a horrific loss, where clearly everyone’s avoiding him.

We were trying to make this scene sound a little bit more ambient by adding more and more sound effects to it. The sound of a shower, the sound of people turning on and off faucets, the sound of murmuring, the sound of lockers opening and closing. And none of it was adding to the story.

But we needed that empty, lonely, echo-y locker room sound. So, we’re hearing a voice-over from a sports announcer who’s tearing Ken to shreds, talking about how poorly he played and how badly things are going for him. Randy had the idea to make it sound like that broadcast was being amplified in the locker room.

It goes from being voice-over that the audience knows to something that’s being played in the scene, and we know everyone in the locker room is hearing it. Ken is listening to it, knowing that everyone else is listening to it. Which just added a psychological layer to the whole thing that made it richer.

And then he had the idea — instead of hearing the last sentence play out, you have the sound of someone off-screen cutting off the broadcast because it’s just too cringy to listen to.

It had nothing to do with music, but it’s just a great example of what final mixes should be about. It’s about storytelling. By adding the simulation of a speaker playing in a locker room, you add a whole layer of storytelling to a scene and really elevate it.

Our thanks to Scot for taking the time to speak with us. As noted above, the film comes out on the 14th, and the OST is already on Spotify, Apple Music and beyond.

2 – Newsbits

Yao: Chinese Folktales was a breakout hit last year in China. The whole thing is now on YouTube in English, uploaded to an official channel that hosts tons of subtitled Chinese animation. Thanks to Catsuka for noticing.

In France, the in-development series Luce and the Lovely Land is making strides. France Télévisions has now signed on.

Also in France, Cartoon Forum is preparing for September. The list of projects is out — Catsuka shared highlights. One in particular we’re watching is Esther from Argentina, whose teaser remains impressive.

After years of decline and scandal, the Japanese studio Gainax (Evangelion) has filed for bankruptcy.

Netflix is promoting its animation slate for the rest of 2024, and there’s a highlight from England: the teaser for Aardman’s new Wallace & Gromit feature.

The Chinese director Busifan is taking his film The Storm to Annecy, and Variety had the chance to interview him.

The government of Canada will require streaming platforms from foreign countries to “contribute 5% of their Canadian revenue to support Canada’s broadcasting system,” reports Kidscreen.

In America, The Last Unicorn is getting a new 4K Blu-ray edition.

In India, Eeksaurus released a 3D mini-episode of its Appuppan series, based on recordings of storyteller P. N. K. Panicker. The first two entries (Seen It! and The Legend of Arana) were hits, and the studio plans more 2D and 3D follow-ups from here.

The state paper Nhân Dân took a look at the animation industry in Vietnam, and its growth in recent years.

Lastly, we told the winding story behind Xiao Xiao (2000–2002), the Chinese Flash series that put stick-figure fight animations on the map.

See you again soon!

I love reading AO's stories that cover the non-animator creatives behind animated productions! So cool. Would love to see a piece focused on an animation screenwriter!

One thing I noticed in the article about Vietnamese animation is that the works being put on the forefront of its growing industry are the cheap content farms targeted at children such as Wolfoo [shudders], which doesn't give much hope for the medium's future there. One may argue that all publicity is good publicity for a nascent creative scene, but I worry that Vietnamese animation will end up attracting a similar stigma China has had to fight to be taken seriously, and unlike China, Vietnam has not, as far as I'm aware, released a film or series on the same caliber as even South Korea's strongest productions.

Besides that, the Ultraman movie looks like a promising watch. I have yet to watch anything from the franchise, but hopefully, this would be a good starting point.