The Best Worst Animators

Plus: news.

Happy Sunday! Thanks for joining us. It’s a new issue of the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and this is the slate:

1) The enduring appeal of AC-bu.

2) Newsbits from the animation world.

With that, let’s go!

1 – Failing upward

For animation, weirdness has been a selling point online for a long, long time.

It helped the Flash creations of the ‘00s, like the classic Tane.1 And it’s especially helped YouTube work. When Michael Epler released his iconic Not So Fast (2019), he was drawing from a whole lineage of odd YouTube animation.

An animator who can craft something surreal, broken or confusing in just the right way tends to get word of mouth. The internet gathers around — even if the project wasn’t done with the internet in mind.

It’s a discovery AC-bu made decades ago. That’s the collective name for Japanese artists Toru Adachi and Shunsuke Itakura — whose animation continues to spread online now, much as it did on early YouTube. They’ve put out ads, music videos and other commissions since the year 2000.

It’s likely you’ve seen their stuff before. They get around. And, from the start, they’ve embraced the bizarre and the badly made. Their process is to take a recognizable idea or style and execute it the wrong way, as if by accident.

Adachi and Itakura have explained it many times: they’re shooting for a “sense of discomfort,” a feeling that things are off. But they don’t shoot for it directly. Instead, they put themselves into the headspace of someone who’d make this work without knowing better, seeing it as “cool.” And then they allow themselves to fail. They want “perfect awkwardness.” The result is uncomfortable, and often funny for that reason.2

Like Adachi told Archipel a few years ago:

If we make something completely different, it would feel [like] we are trying too hard. If it’s clear we are aiming at something different, then it isn’t funny anymore when people notice. So we try to make something, but we slip a bit; this is where people start to see the humor ... we’re really going for that thin line.

Adachi and Itakura may draw like outsiders, but they’re the opposite. The two met in the ‘90s at Tama Art University in Tokyo. They were art-school kids who eyed the big graphic designers of the time. Like their peers, they tried to excel in the traditional way.3

Around ‘97, the two of them and a third friend formed AC-bu. It wasn’t an animation collective then: it was a school club dedicated to video games. The name stood for “Armored Core Club,” after the PlayStation series. They tried to pull in more members — but were afraid to come across as “game otaku.” So, their poster left out Armored Core. It just read “AC,” and featured “pictures of cats and volleyball players.”4

This didn’t help. Yet it did hint at what was ahead. Over time, the club turned into a collaborative art group with its own way of doing things.

The AC-bu guys were deep into it by 1998. Tama’s atmosphere of competition and seriousness had grown “boring” to them. Adachi, Itakura and their friend aimed for awkwardness instead. They found joy in being the weird ones, the rule-breakers, whose art made people laugh when set beside other students’ work. They parodied old ‘70s manga, for example, which they collected for inspiration.5

Bad movies were another source. In Itakura’s words:

... we would go to rental shops and rent tapes that nobody else did ... looking at their covers thinking they could be interesting or crazy. We would then watch them. Sometimes it would be weird ninja movies. There was this series of ninja movies that were mass-produced in Hong Kong; these were very fun to look at and became an influence.

The group gained speed until it won a major award with its school project Euro Boys (1999). Here was a lawless style of animation: grotesque characters, wonky movement, poor use of mixed-media and manic pacing. It was a mess. People loved it.

After graduation, AC-bu couldn’t really claim to be a club anymore — but the name stuck. In 2000, its members started to get attention for their TV ad work (like this one). The “AC-bu style” eventually became a request. Companies wanted it.

Fast forward a few years, and Adachi and Itakura were involved in a TV program that had Isao Takahata of Ghibli on as a guest. He saw their film Japanese-Style Olympics (2003), and his question afterward came to haunt them. “What are you guys going to do after making this?” he asked. They felt he was worried about their futures.

While Takahata’s concern was understandable, it wasn’t necessary. AC-bu didn’t do things the normal way — but it did have a method. Adachi and Itakura (the third member went off to make games) were turning into masters of misusing After Effects and Photoshop to surprise clients and viewers.

“We intentionally try to break down the traditional anime production process,” Adachi said.

Everything they did was, and is, based on getting a rise out of people — just as they had in school. They learned to be inventive: the style “would get old” otherwise, and the reactions would stop.6 And so Adachi and Itakura hunted for the freshly awkward. They found and included a stream of new, strange, grating mistakes.

Early on, their animation was mostly for television. AC-bu’s philosophy (even its existence) wasn’t well known to viewers. In 2006, a writer noted that the group “often [made] mysterious appearances in the niches of the media.”7

But the online world was growing. And, at times, AC-bu went viral — with the story behind the work still murky. One of its music videos, It’s So Good Now (2005), turned into “a hot topic on the internet” and spread as a meme even outside Japan.8

Not all of AC-bu’s early online feedback was positive. When Amazones (2007) streamed live on the Japanese video site Niconico, viewers tore it apart. What was this thing? “It was the first time we were bashed,” Adachi said. He felt relieved that they’d gotten established in the period before social media.

Still, the group’s brand of weirdness suited the internet. During the 2010s, AC-bu projects were hard to avoid online. GAL-O Sengen, a 2011 music video, is a mashup of Japanese gal-o culture (heavy tans, partying, flashy fashion) and half-remembered Dragon Ball Z. It was huge. In 2015, an AC-bu ad for pigeon control and a music video about sushi spread even further. These were just a few of its many, many hits.9

At the time, an official bio for Adachi and Itakura summarized their style in English:

Based on overwhelmingly realistic illustration, their films implant their dense and hi-voltage visual in various mediums and destroy people’s stereotypes by bringing them a new type of audio-visual experience.

AC-bu had found a way to circumvent the anime industry — and traditional animation in general. It was popular on its own terms.

“We mainly make animation, [but] we never really had proper animation training,” Adachi told Archipel. “We never had the experience of working on animation in a professional environment either. We learned everything by ourselves and took it from there.”

It went back to defying expectations. As long as they could surprise people, their own weaknesses were assets. AC-bu and the internet, which runs on surprise, were natural together. In 2018, a magazine asked Adachi and Itakura how they stayed up to date on what might resonate with viewers. “Twitter,” they both replied.

And their work retained the power to shock — even offend — after all those years. In 2016, they did a government campaign (watch) aimed at increasing the youth vote. Regular people saw it. The backlash was brutal: a waste of taxpayer money and an insult to Japanese teenagers, some called it. But voting data implied that it’d worked.10

Then there was Pop Team Epic (2018–2022), the mainstream anime series that finally made AC-bu’s name famous with the public. Adachi and Itakura were hired to create a recurring segment of the show, something called “Bob Epic Team,” which stood out because it was so much worse. They tried to get a rise out of hardcore anime viewers, but were terrified of what they might say.11

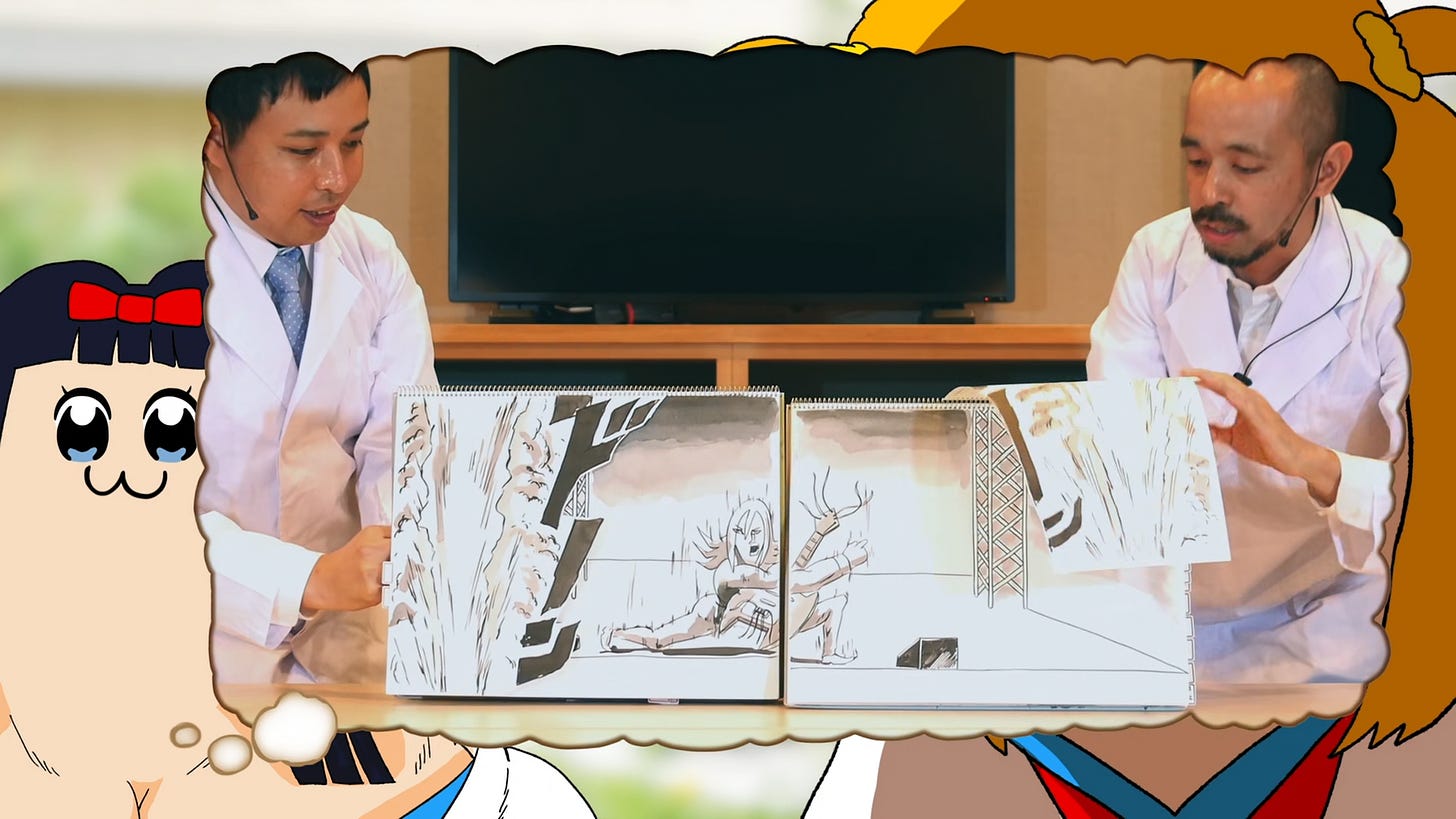

Sure enough, not everyone liked it. But one part in particular, the Hellshake Yano sequence, was a phenomenon.

It isn’t even animated. Adachi and Itakura appeared on camera to do a kamishibai performance (an old-fashioned picture-story show), flipping the pages of a notebook and narrating the action. It was so popular online that, soon, the two of them were recreating the scene live — in an arena, in front of 27,000 chanting fans.

The goal of AC-bu’s style has always been out-of-place-ness. That’s a bit harder today, after 25 years. Many people have seen Adachi and Itakura’s stuff, and its influence is everywhere — especially in Japan, but also abroad. Although they do commercial work, even the weirdest online indie animators tend to take a little from AC-bu.

The hunt for fresh awkwardness continues anyway. AC-bu finds new tricks to catch you off-guard. In 2022, there was Number of Layers 840 — which isn’t funny, but is mesmerizing. Or that music video from a few months ago, which is actually a scrolling motion comic, accessed via webpage or app.

It’s not possible for an animation team to have a successful, quarter-of-a-century run by accident. AC-bu was in the right place at the right time, sure, but that’s not enough. They’ve put real dedication, talent and creativity into this work. The results are terrible — but who can look away?

2 – Newsbits

One of the biggest stories this week comes from America. Jennifer Lee (Frozen) is leaving her position as the creative head of animation at Disney.

Another edition of Cartoon Forum has come and gone in France. One of the best-attended pitches was Esther, an Argentinian project that drew online attention last year with its striking teaser. Meanwhile, Ireland’s Cartoon Saloon won Producer of the Year. See Animation Magazine for more on the event.

In America, the team at the Texas studio Powerhouse has joined The Animation Guild.

Also in America, the trailer is out for DreamWorks’ Dog Man, based on one of the country’s biggest comic series.

Next month, The Remarkable Life of Ibelin hits Netflix. It’s a documentary from Norway about a young man with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, who passed away in 2014. He lived a rich life in World of Warcraft, recreated in the film through animated sequences.

An animated short from Ethiopia, Keffa the Curious Goat, is nominated for awards at festivals in the States.

The Amazing Digital Circus, produced in Australia, will get a new episode next month. Also, Glitch Productions has signed a deal to put the show on Netflix. “We’re still independently funding everything, we still get full control of the show and episodes will continue to always come out on YouTube first,” says Glitch.

American animator Mark Neeley has a new film out, Pure Animation for Now People, with a soundtrack by Mark Mothersbaugh. (Last year, Neeley wrote in this newsletter about a mysterious Beach Boys cartoon.)

In India, there’s a new short-short entry in the P. N. K. Panicker series by Studio Eeksaurus.

Lastly, we shared a rare booklet containing an interview with Faith and John Hubley, the pioneers of American indie animation. See it on the Internet Archive.

Until next time!

The creator of Tane, Brian Lee, has spoken about the project before. Also involved in it: cartoonist KC Green and composer and game designer Toby Fox (Undertale).

Details from this interview, this interview, an official bio and this exhibition listing.

See AC-bu’s official site, this interview and the foregoing sources.

See AC-bu’s interview with Weekly Economist.

From the book Japanese Motion Graphic Creators (2006).

Quoted from this article by Mastered.

For a little about the blowback, see The Sankei Shimbun.

They spoke about some of their fears regarding Bob Epic Team in this interview.

AOS, thank you so much for your awesome stack. It is probably my #1 favorite.

I'm literally going to Tama Art Uni and I didn't even know about these fellas, awsome write up.