Glad you could make it! We’re back with more from the Animation Obsessive newsletter. This is the plan:

1 — the impact of Cat, a Chinese Flash classic.

2 — this week’s global animation news.

3 — a retro ad from the 1960s.

We publish Sundays and Thursdays. New readers — signing up for free lets you receive our Sunday issues every weekend, right in your inbox:

That’s the intro — now, on to the rest!

1. ‘A kind of purification’

Flash is dead, as you’ve heard. Adobe killed it in December 2020. All major browsers dropped support for it early last year. Its disappearance caused a wave of nostalgic, even mournful op-eds on the English-language internet. This was the end of an era.

Yet Flash didn’t truly die — not everywhere. In one country, it’s still being updated even now, as recently as June 14. That country is China, where Flash meant something big from the minute it arrived in the late 1990s.

It’s hard to explain Chinese Flash animation to the outside world. When it appeared, it was different. Larger. In the early 2000s, the Flash scene wasn’t just a niche for anarchy and weirdness in China — it was a massive, generation-defining creative outlet. It was like early YouTube before early YouTube. As researcher Weihua Wu has argued, it was like the new rock and roll.1

That’s a bold comparison, but not baseless. Early Chinese Flash cartoons were the art of the internet, with all of the newfound freedom that entailed in China. Young artists and amateurs made their personal feelings public in raw, unfiltered ways — often for the first time. And they went viral in the process.

Which happened, in late 2002, to a Beijing artist named Bu Hua. She made a five-minute Flash animation, Cat (猫), that brought hundreds of thousands of people to tears. Then she was on China’s national news.

Cat is a story of love and death — the connection between a parent and child, and the pain of the parent’s passing. “Two tramps on the way... mother and son,” reads the film’s opening text, in English. By the end, the son has journeyed into Hell itself to save his mother.

Like its contemporaries, Cat is raw. There’s beauty to the film, but parts of it are unpolished, even haphazard. It’s a product of its time — as with the Flash scene itself, its cultural moment in China belongs to the 2000s. But that didn’t matter back then. What mattered was that Cat did, and still does, make you feel. It’s raw, yet that’s also the reason it’s so hard to look away.

“Every time I watch Cat, my heart feels a kind of purification, and my soul is moved,” wrote one Chinese fan in 2003. Most who saw Cat said the same. At the time, a media outlet dubbed it a film that made “people cry at least eight times.”

It all came from a personal place for Bu Hua. She wasn’t an online radical herself, or even an expert Flash user. But this little program had set her free.

The daughter of a painter, Bu explained that she “majored in painting in college, and, at that time, computer painting was still far to come.” After graduating in 1995, she studied abroad in the Netherlands before returning to China. All along the way, she struggled to find her place, her style. She spent a few years trying to make experimental live-action films, without success.

Then, in mid-to-late-2001, Bu got her answer. Reacting to one of her film ideas, a friend said, “Have you heard of Flash? That’s the trendy thing to do.” So, Bu decided to check it out. As the state-owned Beijing Evening News reported:

When she went to the bookstore to look for Flash software, she found that Flash had caught on like wildfire, and the textbooks for Flash production alone filled a whole bookshelf. She picked one of them and took it home to learn from scratch. After one afternoon’s work, her Flash [animation] was moving.

Even for Bu, a total outsider, Flash quickly became second nature. She was drawn into the online Flash scene, centralized on Chinese sites like Flash Empire. One popular creator she admired was Xiao Xiao (whose Xiao Xiao Works series invented the “stick-figure fight” genre).

Bu’s own films stuck out partly because of her classical training, and partly because they were more mature and emotional than the average Flash. For her, emotion was very much the point. “I’ve always been wishing to express emotion with great impact, and painting is not suitable to be its vehicle,” Bu later said. “While making these shorts, I tried to learn how to express emotion better.”

In November 2002, after making around 10 animations, Bu stumbled across an audio file she’d downloaded the previous year. It was the theme to The Last Emperor, a gorgeous piece composed by Ryuichi Sakamoto. (Bu said that she “couldn’t help crying” when she first heard it.) So, she decided to animate to it.

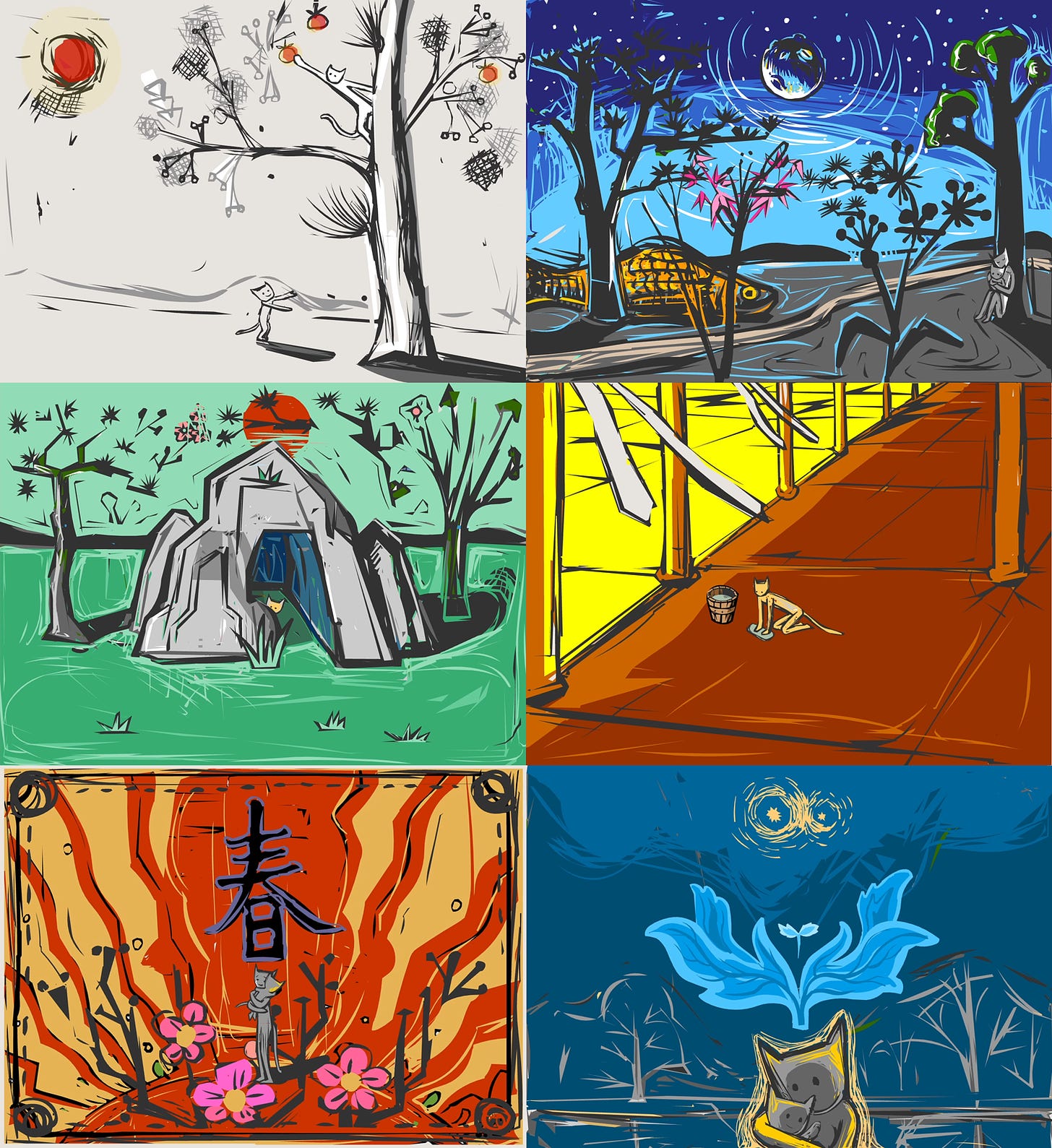

Bu built Cat’s story and concept to match the music. The film’s themes, she argued, could “be summed up in two words, namely ‘love’ and ‘courage.’ ” Her art for Cat leaned into expressionism, which visibly strains against Flash’s vector shapes — somehow forcing its way through.

And it was, again, deeply personal. “My father had passed away just after my graduation,” Bu later admitted. “The shock, panic and sorrow it had brought to me were also released in [Cat].”

The whole thing took her a little over a month, all in Flash, with no script. It was her first animation done with a drawing tablet (“indeed more flexible than a mouse,” Bu noted.) And then it went out to the world.

It’s hard to see the result in its original form today — unless you’re adventurous enough to download an archived SWF copy and open the file with Ruffle. For most of us, YouTube is the easier option:

In any case, Cat was a hit, and it made Bu Hua’s name. Seen today, it has an urgent, almost fevered quality that refuses to be ignored. It feels like the fruit of desire — created because it needed to be created, right then, no matter how flawed it might become in the process.

But that was the era. Artists like Bu were being set loose. Guerrilla filmmakers were popping up online even as China’s “real” animation industry was floundering, often devoid of creativity — at a time when economic change and government policy had caused a dark age for animators. Flash offered an alternative to people who were dying to express something personal.

Asked in 2003 whether Flash could revive Chinese animation as a whole, Bu said yes. It would, she argued, bring personal artistry back to the medium. Animation was now open to every individual voice that wanted to speak. She put it simply in another interview: “Flash can help people realize their dream of being a filmmaker.”

Thanks in no small part to Cat, that’s what happened. The Chinese Flash scene gave birth to modern Chinese animation. In fact, films like Big Fish & Begonia and The Legend of Hei started out as amateur Flash projects. The rising star Zhou Fangyuan, who we interviewed last year, first fell in love with animation because she saw Cat as a child.

That was the power of Flash in China. Flash itself may be fading now, and gone in the rest of the world, but the dream of independence and personal expression that it inspired in Chinese artists is still alive. It’s just taken new forms. If you spend a little time, you can dream it, too.

2. Global animation news

The slow-motion collapse of Russian animation

Since February, we’ve chronicled the effect that the Russian invasion of Ukraine is having on animation in both countries. These updates aren’t for everyone, but we feel it’s important to record this moment. It’s a microcosm of the disaster that Putin has caused.

Regular readers know that the invasion has dealt a self-inflicted blow to Russian film and TV, animation included. Boycotts and sanctions have cut it off from the money and recognition it needed to thrive. Everything is different — and not just economically. A quote from producer Dzhanik Fayziev put things into perspective this week:

Of course, everyone dreamed of getting an Oscar — this is the most important award in the film industry. We dreamed of being on Netflix. Not because there are millions there […] But simply because it’s a recognition of excellence. Now, with all of it out of reach, there has been a collapse of criteria among a huge number of my colleagues — how do I evaluate my work if a big foreign producer can’t tell me I’m doing well?

That said, the biggest problem remains the economic one. Russia’s most famous animation studio, Soyuzmultfilm, has been withering for the last four months. It’s a state asset, widely covered by state-run media — and it’d been growing quickly before the invasion. None of that has protected it.

Recently, Soyuzmultfilm head Yuliana Slashcheva projected that her company’s revenue would drop by 30% in 2022. It’s trying to find international partners to replace the ones it’s lost in Europe and beyond, recently signing a distribution deal in China for over 1,000 of its projects. But the losses won’t stop.

Earlier this month, Soyuzmultfilm’s long-running effort to privatize (and thereby increase its profits) was foiled again. The plan was for Sberbank to buy a stake in it — until sanctions crushed Sberbank, and it backed out of the deal. Reportedly, all stock in Soyuzmultfilm is still held by the government. Sberbank also dropped a subsidiary that it’d been co-running with Soyuzmultfilm.

Meanwhile, there’s a growing problem with animation software, as licenses expire and new ones can’t be bought. It’s quickly becoming an industry-wide crisis, Slashcheva said. Studios are scrambling for alternatives — and running out of time.

Best of the rest

Until July 1, The Animation Guild is voting on its new contract. If you’re in the union, don’t forget. Story artist Katie Graziano notes that “things are not going to get better if we cannot get our members involved for even this simple thing.”

The Irish trade association Animation Ireland dropped an exciting new reel — showcasing the huge volume of animation coming out of the country lately.

A new Ukrainian program is in the works to support film and TV, including animation, amid the war. The plan is international co-production.

The animation world is still sifting through the results of the Annecy festival in France. See Cartoon Brew’s round-up of Latin American standouts, plus its spotlight on the “first traditionally animated feature” from Pakistan.

A tweet from American story artist Dylan Holden (Monsters at Work) caught our attention. “I think without fundamental change to the craft, we should more or less consider a new job title,” he wrote. “Rough Story Animators.”

A Russian court of appeals overturned a ruling on Peppa Pig that had allowed a man to use the character in violation of international law. Apparently, the brand is protected in Russia again.

Regular readers know that it’s graduation season in China. Don’t miss the pictures and GIFs coming out of the A Da Experimental Class at Beijing Film Academy.

In Scotland, the latest report shows that artists in the country earned £20.3 million from animation in 2019. (Outsourcing accounted for all but £500,000.) The next report, focusing on 2021, will show the impact of the pandemic.

Lastly, we wrote our most in-depth piece ever on the art of filmmaking — all while uncovering the avant-garde roots of Gumby.

Thanks for reading this far! We hope you’re enjoying today’s issue.

The last part of this newsletter is for paying subscribers (members). Our subject is a retro ad for Ford by Playhouse Pictures, directed by Bill Melendez (A Charlie Brown Christmas) and co-designed by the great Sterling Sturtevant. Luckily, there are lots of interesting details about it.

If you’re not a member, we’ll see you next week! Everyone else, read on.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.