Welcome! For your enjoyment, we’re back with another edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Here’s what we’ve got this week:

One — how Don Bluth turned Disney upside-down from his garage.

Two — the week’s top animation news, worldwide.

Three — the last word.

Haven’t signed up yet? It’s free — and zero-effort. You can keep up with our latest issues right from your inbox, every Sunday:

With that out of the way, here we go!

1. Don Bluth’s accidental uprising

Studying the art of animation has never been easier — even if you don’t go to school for it. Blender is a powerhouse, and the software that Studio Ghibli used to make Spirited Away has been free for years. On the internet, all the world’s animation is at your fingertips. And online tutorials break down every part of production.

Today, respected animators like Ian Worthington are teaching themselves.

So, it’s hard to picture Don Bluth’s situation. Back in the early 1970s, he was the up-and-comer at Disney. Walt had died a few years before, and the famous Nine Old Men were getting older. The studio still trained new talent — but Disney’s classic filmmaking had started to slip away, right alongside the veterans who’d pioneered it.

As Bluth remembered, older technical tricks like the “shadows or the reflections or the double passes through the camera” were “evaporating before our very eyes.”1 The problem was bigger than that, though. Bluth and many of the other young trainees didn’t know how to make a movie, and they weren’t sure how to learn. According to Bluth’s colleague Gary Goldman, “We didn’t even know what questions to ask.”

“We were learning to animate,” Goldman remembered. “We were learning to inbetween, clean up … and we said, ‘Wait, there’s so much more we need to know.’ ”

That included writing, scene planning, editing and more. Even the Nine Old Men had “forgotten” much of what went into Disney’s older films, animator John Pomeroy said. Bluth recalled asking Frank Thomas the secret behind Fantasia’s water, only to be told that “no one ever wrote that down.”

The new recruits couldn’t use the studio’s tools to rediscover these secrets, either. As Bluth explained:

Disney was a union house. We couldn’t touch any of their equipment to experiment … We couldn’t even plug the Moviola in to look at what we were doing. Or use a cutter, or anything, because it was all union. And we were not in that union.

Management said that the Nine Old Men would retire within five or six years. Bluth, Goldman and the rest would soon fill their shoes — with only a rudimentary sketch of what the masters once knew. They needed, and wanted, to learn faster. Hoping to bridge the gaps in their knowledge, Bluth started a side project. An independent cartoon made with independent equipment. In his garage.

The idea didn’t stem from a desire to escape the company. “We were actually very enthusiastic about working at Walt Disney Productions, almost obsessive about it,” Goldman said. Setting themselves up in Bluth’s garage was simply a way to learn the skills they needed, on the side. It was a school — a “sanctuary,” as Bluth put it.

According to Goldman, Bluth already owned a Moviola and an editing bench — he’d bought them to study “old 16mm Warner Bros animation reels.” Gathering a few more production tools, a small team formed in 1972. Their first project, The Piper, was based on a long limerick written by Bluth’s brother Toby.

Bluth, Goldman, Pomeroy and a number of others spent years on The Piper alongside their Disney work. The de facto head of Disney’s animation branch since Walt’s death, Wolfgang Reitherman, supported their effort to learn. They ended up storyboarding 20 minutes and animating around four (watch a few seconds here).

In 1975, they brought in the legendary John Lounsbery to assess The Piper. It didn’t go well. Bluth again:

It was excruciatingly painful, actually embarrassing to watch with one of the Disney animation masters sitting in my living room. It was then that we realized that the story wasn't appropriate for a short; too much information in too short of a time … The very next weekend we decided to scrap The Piper and chose something simpler.

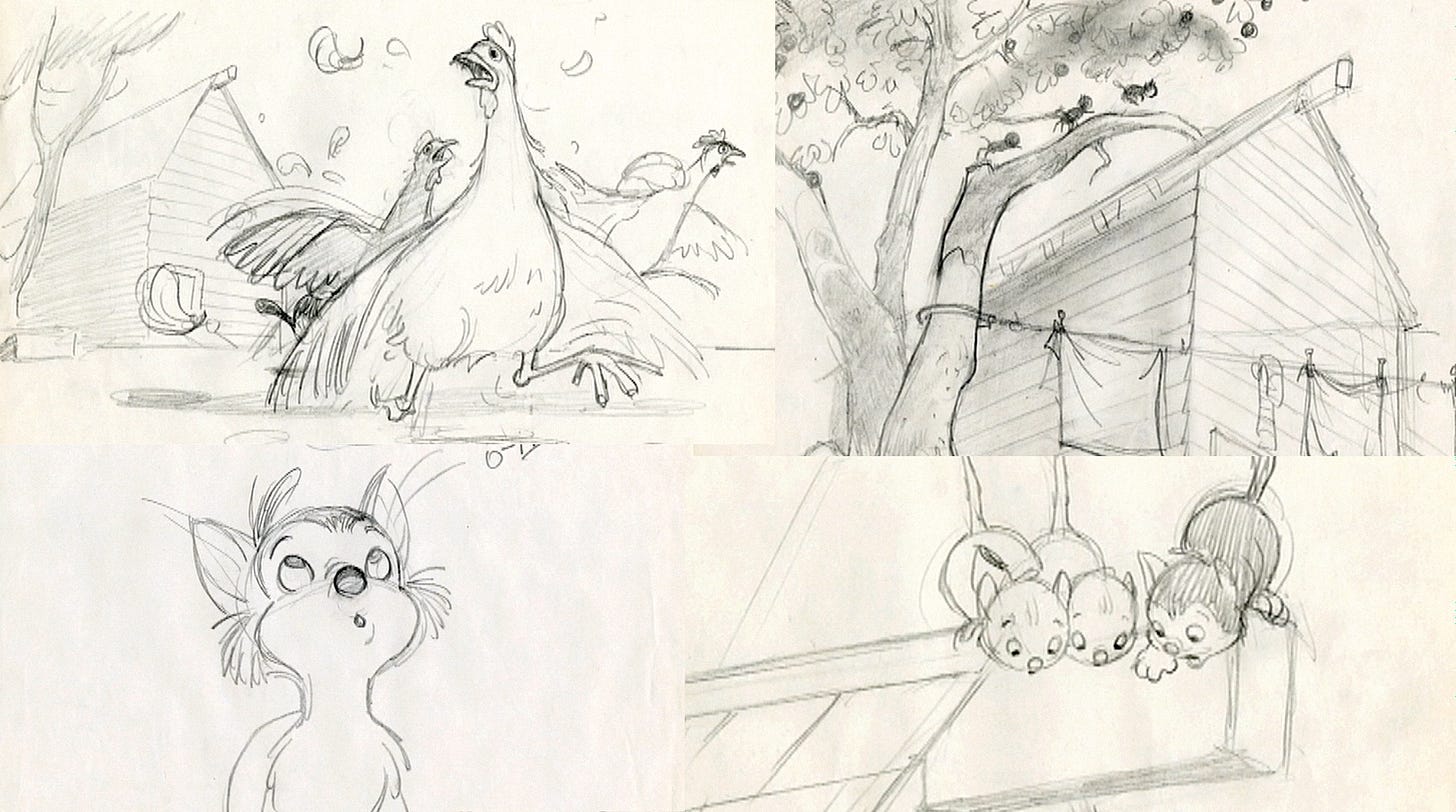

That simpler project would be Banjo the Woodpile Cat, which they planned to do in a year. The idea was based on a kitten from Bluth’s childhood. It seemed easy enough. They started in March 1975 — and didn’t pull across the finish line until December 1979.

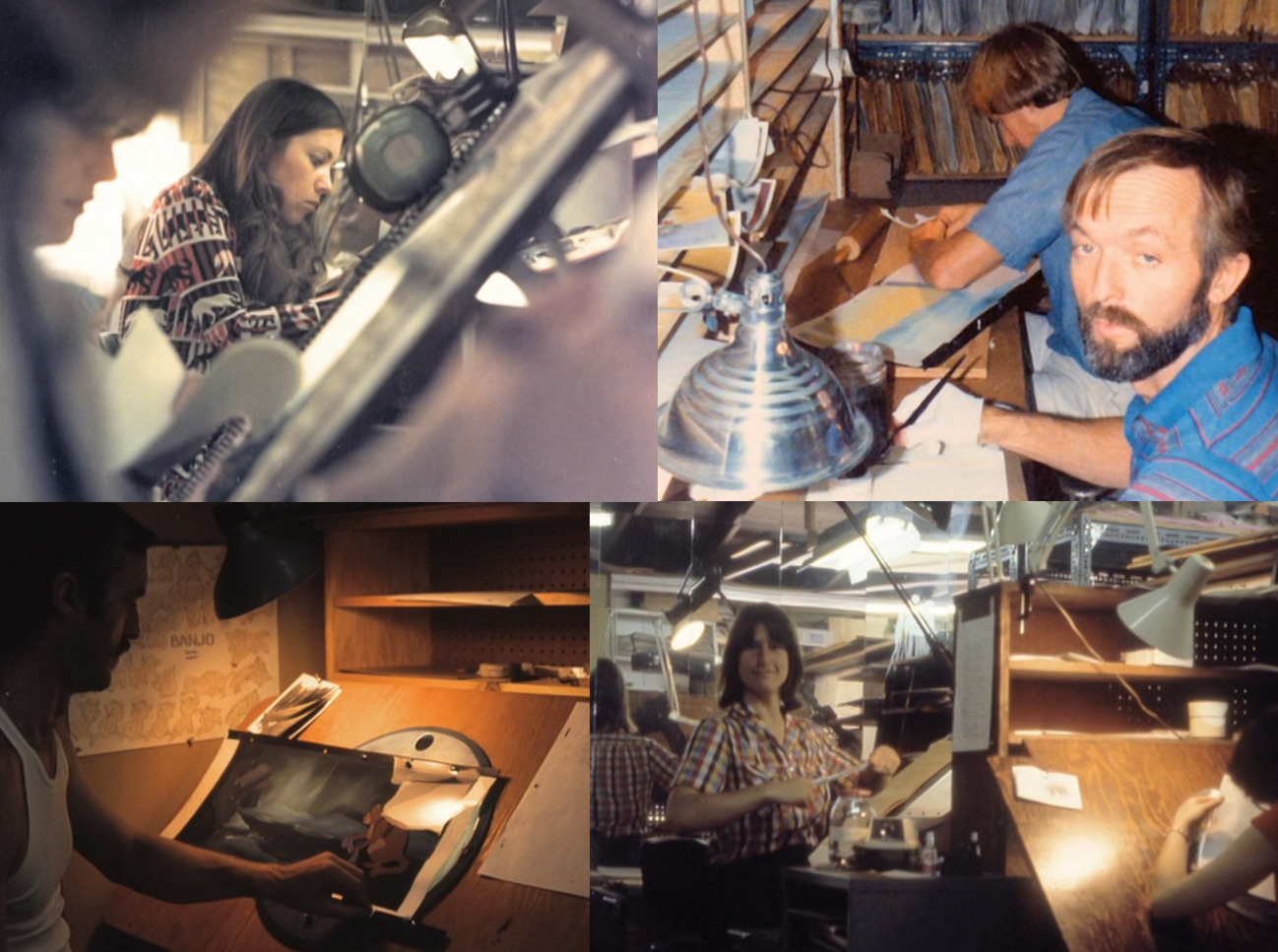

Banjo was “an underground animation campus,” Pomeroy said. The learning environment proved magnetic, and a parade of Disney staffers came through to work on Banjo part-time. Animator Linda Miller recalled that she “wanted to learn more about filmmaking … and it also seemed more exciting than the projects that Disney was working on.”

“They would teach animation to any artist interested,” Dorse Lanpher later wrote. A number of women from Disney joined up — around four minutes of the film were animated by Miller, Heidi Guedel, Emily Jiuliano and Lorna Cook. If someone wanted to learn by working on Banjo, Bluth remembered, they “never turned anyone away.”

This was a very-1970s guerrilla production. Before it was over, Goldman had stolen rain and snow overlays from Disney’s garbage. A young Glen Keane created the sound effects for a truck’s exhaust pipe. Bluth, Goldman and Pomeroy animated most of the film, but Bluth’s main memory of Banjo was mixing cel paint by his swimming pool.

Bluth had experience doing layouts at Filmation, so he handled all of Banjo’s storyboards in his detailed style. Pomeroy built on Bluth’s sketches with ink and sometimes color — a single drawing could serve “as layout, pose test for the animator and then eventually a … color sketch for background and lighting and effects,” Pomeroy said.

All of this learning quickly started to pay off. When Bluth got the co-director role for Pete’s Dragon at Disney, he consistently relied on lessons he’d picked up from Banjo. Pomeroy had the same experience as an animator on Pete’s Dragon.

Even then, the roadblocks multiplied. Feuds formed at Disney, and some were derogatory toward the “Bluthies” in the garage. The younger set from CalArts, like Brad Bird and John Musker, shared Bluth’s unhappiness with Disney — but didn’t get along with him, either. Meanwhile, Banjo itself was dragging on and on. As Bluth said:

About four years into this … we wondered if we would ever recoup our investment of time and money. Then, in late 1978, we thought, what if we took it to Disney, they might agree to buy it and let us finish it there during regular work hours.

Disney wasn’t interested. Combined with Bluth’s bad experience directing The Small One at the studio, the writing was on the wall. “All of our learning is only going to do us any good if the higher-ups will accept what we’re trying to make happen,” Pomeroy remembered thinking. There was a sense among Bluth’s garage team that Disney didn’t care to implement most of the lessons from Banjo.

Much has been written about the walkout that Bluth, Goldman and Pomeroy staged at Disney in September 1979. It was a huge event in the animation world, even hitting the national news. The late Michael Sporn once wrote, “I can’t exaggerate the excitement this caused in the ‘young’ animators at the time — even 3,000 miles away.”

Quite a few who’d learned at Bluth’s school-studio came along, including Disney’s entire staff of women animators. At Disney, Bluth told The New York Times, women were rarely allowed to advance past the assistant role in animation. Given a chance to learn more, figures like Lorna Cook became forces of nature.

Banjo enabled the walkout — and not just because it taught the team how to make a movie. Outside investors had asked Bluth and Goldman, while they were at Disney, if they wanted to quit and do their own film. Bluth only had to prove that he could make one. He showed them Banjo, which was “about 90 percent animated and about 70 percent in color,” and was handed millions to finish it and produce The Secret of NIMH.

At the newly established Don Bluth Productions, Banjo had a nail-biting final crunch. It got a limited run in California theaters during December 1979, and later aired on television. Bluth has readily admitted that the film isn’t a classic. But it did give him and his team the skills to craft one.

After four and a half years of learning on Banjo, the team had a hunger to make a truly great feature film — and they finally knew how to do it. Even Banjo’s flaws were fuel, in the end. “What we were not able to do on Banjo and we were learning on Banjo,” Pomeroy concluded, “we carried on through The Secret of NIMH.”

2. Headlines around the world

Annecy approaches

Annecy, the world’s premier animation festival, begins in France on June 14. This week, the last major teasers and previews dropped in the run-up to the event.

Per a French report on Wednesday, one Annecy highlight will be the rare work of the Frenkel brothers — the fathers of Egyptian animation. Several of their restored films will show at Annecy this year, alongside a 52-minute documentary. Another Wednesday story pointed out that The Crossing, billed as the world’s first animated feature made with paint on glass, will also be on display.

On the business side, Annecy 2021 has a new mentorship initiative for French-speaking women from France and Africa. And Triggerfish, in related news, picked up an Annecy award this week for its expansion in South Africa.

Like last year, Annecy 2021 is a hybrid event — held both in-person and online. Even if you’re nowhere near France, you’ll be able to stream most of the festival’s offerings with an inexpensive Moviegoers Online pass. It’s available until June 18, the day before Annecy ends. We already have ours. Next week, we’ll be covering the best of Annecy right here in the newsletter.

African animation continues to blossom

Just above, you read about Annecy’s new mentorship program for French-speaking animators in Africa. Last week, we reported that Gobelins is holding animation courses in Ghana. It’s all part of a trend. African animation is on the rise, and investors and schools in Europe have decided to lend it a hand. As the Forbes headline put it last year, “Africa Angles To Be Animation’s Next Global Hotspot.”

This week brought more signs of African emergence. First, we learned that Cartoon Network Africa has put Garbage Boy and Trash Can into production. Its self-taught creator, Ridwan Moshood of Nigeria, won a contest with the show’s pilot in 2018. A brand-new studio will produce Garbage Boy in South Africa, the continent’s current animation hub.

Second, France revealed even more training initiatives this week. African Creative Talents will open a Moroccan animation school in January 2022. As the group’s Mounia Aram puts it, “The talent is there, but they lack training.” Meanwhile, Gobelins unveiled a shorts program called Bridges, meant to bring African cartoons to the world stage. Its first film, Red Ants by Mogau Kekana, premieres at Annecy 2021.

Developments in Indian animation

A few India-related news stories caught our eye this week. The first is a somewhat technical look at the success of Sprout Studios on smart TVs. Two others highlighted the continued importance of outsourcing jobs in Indian animation.

In early June, Variety reported that Rob Edwards, a screenwriter from The Princess and the Frog, would direct a film called Sneaks. As Animation Xpress pointed out on Monday, that film’s animation is being done in Mumbai. Also, we learned this week that the upcoming Kingdom of None will be co-produced in India, a switch from the original plan to animate it in Canada.

Lastly, don’t forget that Vaibhav Studios of Lamput fame is pitching a new series at Annecy. Called Kuttan the Medicine Boy, it was among the 37 pitches selected for the festival — out of 433 entries.

Best of the rest

On Friday, the American animator Ian Worthington dropped a new episode of his popular web series Bigtop Burger — the first in almost a year.

Also in America, Netflix released the first stills from Maya and the Three. Spearheaded by Jorge Gutierrez, the long-awaited show draws on Mesoamerican lore.

This week saw two birthdays for Soviet-era animation studios. In Russia, Soyuzmultfilm turned 85 on Thursday. Meanwhile, the Hungarian company Kecskemétfilm turned 50 on Friday.

Another from Russia — the Ministry of Culture proposed a bill that would overhaul the country’s legal framework around creative industries. It’s an effort to inject even more government support into the arts, including animation.

The latest film by American studio DreamWorks, Spirit Untamed, bombed at the box office. Reportedly, it’s the studio’s worst opening ever. A shame, as the Netflix series it adapts had a lot of heart put into it.

Fresh off the global festival success of Nahuel and the Magic Book, director Germán Acuña Delgadillo of Chile has revealed his new film — The Devil’s Vein.

Intensifying its push into animation, the American company Technicolor will restructure. It’s folding its animation branches into Mikros Animation — the Technicolor subsidiary behind The SpongeBob Movie: Sponge on the Run.

3. Last word

And that’s it! We hope you liked this week’s installment. Technical issues, including a long internet outage, forced us to cut it a little shorter. Next week’s special Annecy edition will be jam-packed, though, so stay tuned for that.

One last thing. We’ve been enjoying another newsletter that started on Substack recently — The Line Between by Coleen Baik. It’s one of the few Substack publications about animation, and the only one as active as our own. Baik is a talented New York animator who uses her newsletter to offer a peek behind her craft. Her update this week is loaded with insights and process GIFs, and it’s well worth a read.

Hope to see you again soon!

These quotes, and a good deal of the article’s other quotes and information, derive from extras on the Banjo the Woodpile Cat DVD.

Wonderful issue! Thanks also for the mention and kind words—unexpected and much appreciated.