There’s a certain idea about ‘50s animation. It’s died down a bit since its peak in the ‘90s and ‘00s, but you still see it around. And it goes like this: mid-century cartoons were a little naive.

There’s a sense that people, animators included, weren’t as self-aware back then. The ‘50s were defined by an aw-shucks, gee-whiz mentality. There wasn’t a real grasp of human nature, or a cynicism toward the corporate world. Cartoons were simple, optimistic, squeaky clean and untroubled by irony. They weren’t in on the joke.

The more you engage with the ‘50s and their animation, though, the shakier these stereotypes feel.

Set aside Leave It to Beaver and the unrealistic ads. Many thinkers and artists who helped to define the ‘50s, even beyond animation (James Baldwin, John Coltrane, Mark Rothko, Sylvia Plath), were scarily modern. And, in animation, the people in UPA’s orbit could be more knowing than we are today.

Take Ernest Pintoff. Years before he won an Oscar for The Critic (1963), his cartoon with Mel Brooks, Pintoff worked at UPA. He started there in 1955, as an artist on The Boing-Boing Show. He was a painter and jazz musician fresh out of college — and his work tended to be intensely self-aware.

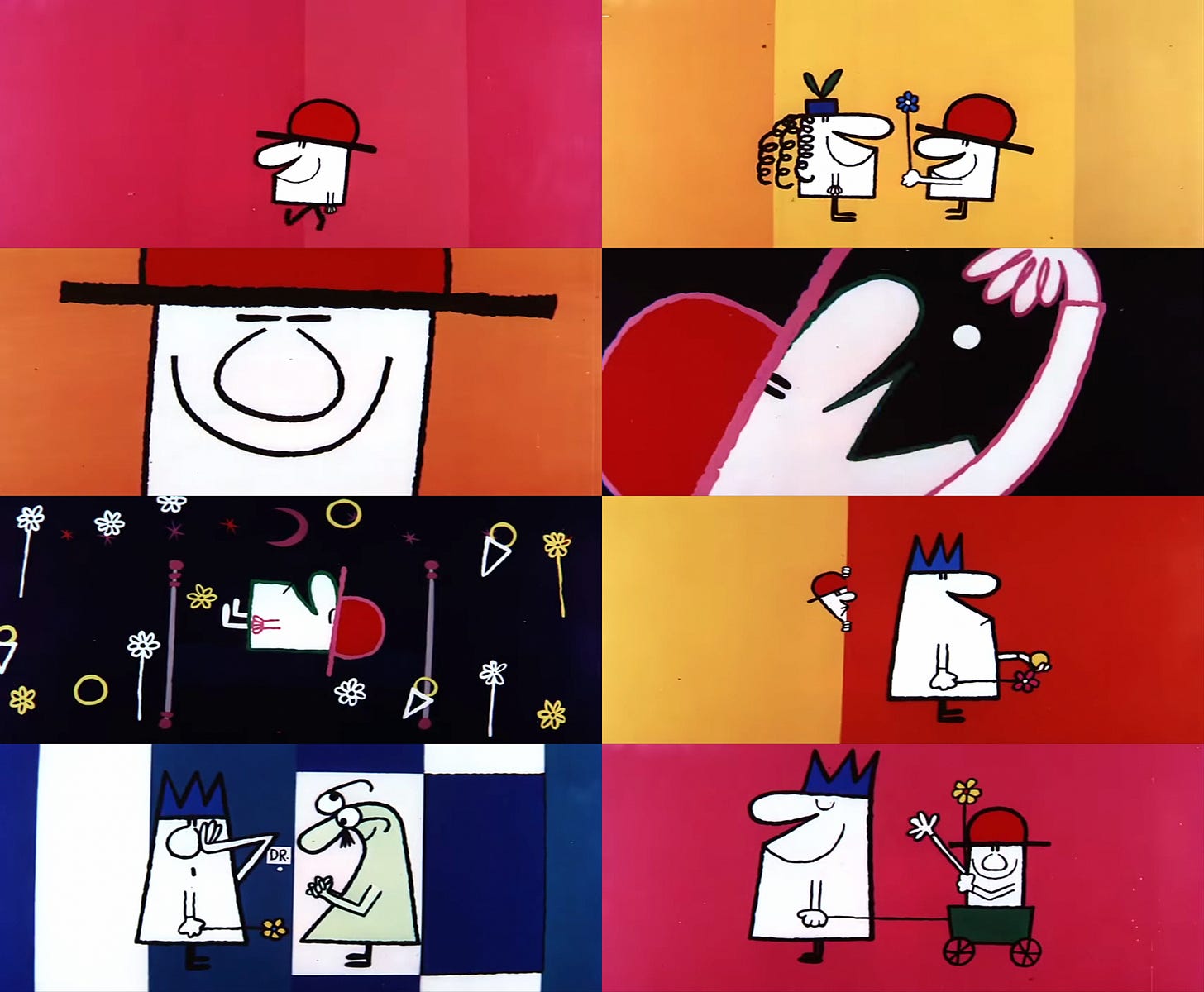

How self-aware? When he left UPA in 1956, Pintoff answered that question with a film called Flebus (1957), made at Terrytoons. It’s one of the most unique cartoons of its time. And it’s so ironic that it almost hurts.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.