The Making of 'The Last Unicorn'

Plus: animation news.

Happy Sunday! We’re back with more from the Animation Obsessive newsletter. Today’s lead story has been in the plans for a long time — we’re very excited to share it. Here’s what we’re doing:

1️⃣ The story behind The Last Unicorn (1982).

2️⃣ Animation news worldwide.

Just finding us? You can sign up to receive our Sunday issues for free — get them right in your inbox:

Now, let’s go!

1: The unlikeliest classic

The Last Unicorn is the definition of a sleeper hit. When it reached theaters in 1982, its box office returns weren’t huge — and some reviewers hated it. But it kept going. It ran for months at certain locations, and its later VHS editions (and TV airings) grew its audience over time.

Today, the film is one of the best-loved projects by Rankin/Bass, up there with Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. It may not have Rudolph’s degree of fame, but it’s known by the people who know.

Which is pretty impressive for something so quirky. This tale of a unicorn’s journey through a whimsical land is heavy on dialogue, and it progresses in a winding way, and it looks weird. From the first minute, it’s obvious that The Last Unicorn isn’t a Disney film. It’s much harder to put your finger on — but its charm is just as hard to deny.

A good deal of this charm and idiosyncrasy came from screenwriter Peter S. Beagle. He also wrote the original novel, The Last Unicorn (1968), that the film adapts. Its unique energy carried over into his screenplay. The book was (and is) a cult hit in its own right — even though Beagle has called it “the hardest, least fun thing I’ve ever had to write.”

The animated Last Unicorn didn’t come easy, either. In fact, getting it made in America was so tough that it really wasn’t made there, once all the deals were inked. Topcraft, the same studio that would produce Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) a few years later, created most of the film in Japan.

The road to The Last Unicorn was very, very bumpy. Michael Chase Walker, the producer who ultimately pushed the project through, jokes that “a kind of curse” has always hung over it.1

Interest in an animated Last Unicorn movie came early. The 1968 novel was Peter Beagle’s first major success as an author — it was a hit. Even the team behind A Charlie Brown Christmas wanted to animate it. By 1972, a production company called Balaban & Quine had optioned the rights.2

But it went nowhere. That pattern would repeat itself for many years to come. As Beagle put it, the film was “always almost getting made” and then fizzling out. “[R]ight to the last I never expected it to be a movie,” he said.

The problems continued even after Walker got involved. He was a young, scrappy independent producer — darting from New York to Illinois to California — who’d fallen in love with the novel in 1974. It took him around two years to pull the rights away from Balaban & Quine, but he was determined. He managed to buy a year-and-a-half option for The Last Unicorn in 1976.3

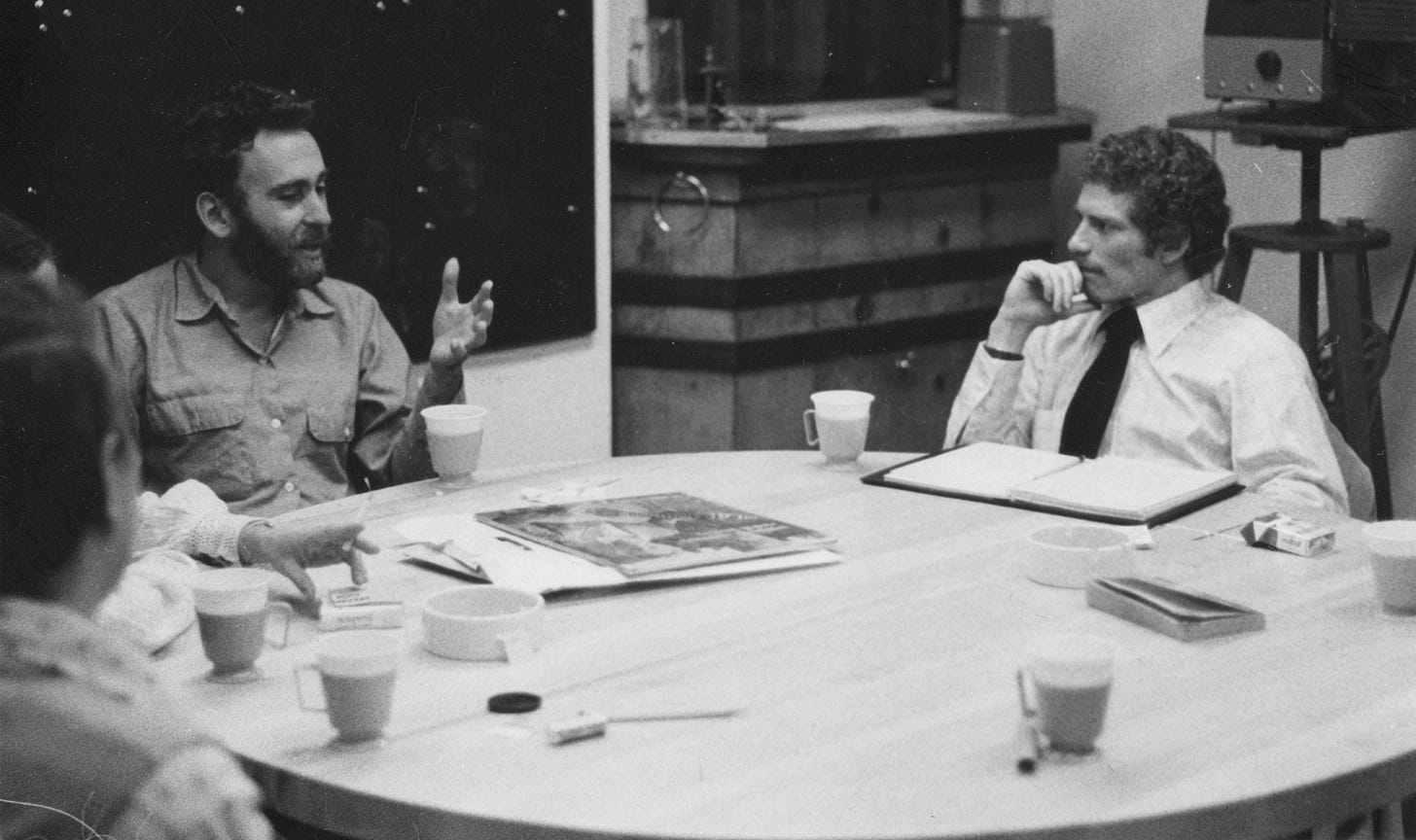

With this in hand, Walker pitched the film around Hollywood and had plenty of meetings, but once again no progress. As he’s said:

What I found out was something you’re not really told about when you try to stick your toe in the film business. Which is, if they like the idea and you have the option, the biggest strategy is that they’ll wait for the option to run out and then option it themselves. Because they know you can’t pour constant money into it. So, between the time that I was producing animated commercials in my studio, that’s what I was finding. You know, I would meet with everybody, but you’d never hear back from them because they’re waiting for the option to run out.

Maybe two weeks before the deadline on his option, Walker took a gamble. He bought the film rights altogether — for a sum in the ballpark of $200,000 in today’s money. Beagle got paid (“the biggest check I’d ever seen,” he said) and Walker started bargaining again with the studios. Luckily, for once, the timing seemed right.

Right then, hype was growing for Ralph Bakshi’s The Lord of the Rings (1978), and Beagle himself wrote its script — having “stumbled into screenwriting” some years before. This helped to draw studio attention toward The Last Unicorn, as did its fantasy theme. Walker was hoping for $5 million to do the movie, and it looked like he might actually get it.4

In 1978, Warner Bros. signed a development deal with Walker for a reported $25,000 per month (around $120,000 today). As he said, “I literally went from living in a lean-to in my brother’s back yard to a gorgeous house in the hills in less than a month’s time.” Warner was behind Lord of the Rings and, in the lead-up to the premiere, was hedging its bets. If the film went big, the studio wanted a similar project to follow it.5

But the curse struck again: Lord of the Rings posted mediocre numbers, The Last Unicorn was dropped and Walker’s money from Warner turned into debt to Warner. The situation was bad — Walker was desperate.

Around early 1979, though, he made the connections that would realize his dream project.

Walker’s pitch caught the eye of a studio called Marble Arch Productions in California. By chance, Arthur Rankin and Jules Bass were in touch with the same studio, and they’d recently taken an interest in adapting The Last Unicorn as a follow-up to their TV film The Hobbit (1977). So, Marble Arch brought everyone together and a deal was made in mid-1979. The two studios would produce The Last Unicorn for theaters.

Finally, Walker had his movie — but at a cost. Rankin/Bass was basically his last choice for a production studio: he “really couldn’t stand their animation.” Beagle was even unhappier with the deal. “I hated everything Rankin and Bass had ever done. Everything,” Beagle explained. “Didn’t like what they’d done to Tolkien. I hated Frosty the flipping snowman, let alone Rudolph the whatsit.”6

As he said in 2014:

I remember screaming at Michael Chase Walker because I was horrified when he told me Rankin/Bass was gonna be doing it. And I screamed, “Why don’t you go all the way and sell it to Hanna-Barbera?!” and he said very solemnly, “They were next.”

Even so, fear soon gave way to a little hope. When Beagle was initially hired to write the screenplay, he cut it down to a pale imitation of his book. “[I] just figured that that’s the way they go about things; I might as well do it myself,” he recalled. Yet Jules Bass asked him to stick closer to the original story.7

It wasn’t what Beagle had expected. “In fact, they [Rankin/Bass] were surprisingly easy to work with, they respected the material, and they did better with it than really anything of theirs I had ever seen,” he said. Beagle wasn’t involved with the film after the script was finished, but the production stuck pretty close to his words — even though his screenplay read almost like a novel.

It should be noted that Rankin/Bass wasn’t really an animation studio. It produced animation — but its contributions usually ended at concept work, scripts, voices, music and general oversight. The actual animation went to Japan, where Rankin/Bass outsourced to a whole network of studio partners.

Tokyo’s Topcraft, which had done The Hobbit for Rankin/Bass, was put in charge of The Last Unicorn. The project started at the studio in 1979. Topcraft received a scratch track and Beagle’s screenplay, plus initial sketches by artist Lester Abrams. But even the storyboarding, as researcher Makoto Kuroda has discovered, was done in Japan.

“Topcraft was trusted for its production skills,” Kuroda explained. The Tokyo team was even “allowed to change the content and add sound effects to accompany it within the time limit.”

In those days, Topcraft’s foreign cash gave it higher budgets than most of the surrounding industry. Documents from the studio, unearthed by Kuroda, reveal that The Hobbit used 380 different colors compared to the 80–130 then typical in anime. A half-hour anime episode might take 4,500 frames of animation, but The Hobbit used around 40,000. Stats for The Last Unicorn were similar: 75,000 drawings, 260 colors. And the static (tome) shots seen in anime were “avoided as much as possible.”

According to animator Hidekazu Ohara, who worked on The Last Unicorn, Topcraft prided itself on its quality. There was a certain sense among the staff that its work outshone the competition in Japan. Part of that assurance came from a legendary artist named Tsuguyuki Kubo, who was a guiding force at Topcraft — and on The Last Unicorn.

As one American commentator has said, Kubo had “a profound impact on the look and feel of the entire thing.”8 He co-storyboarded the film with technical director Katsuhisa Yamada, and co-designed the characters with Lester Abrams. Kubo was an ace from ‘60s animation (he’s still active today) and widely respected in the industry. His surviving character concept work for The Last Unicorn, much of it dated to November 1979, is stunning.

Like all Rankin/Bass productions, The Last Unicorn was iterative. After Topcraft translated the script and developed the designs for the characters and world, and created the storyboard, its work was sent to America for corrections and additions. (Don Duga is credited as an additional storyboarder on the American side.)

Topcraft’s storyboards became the basis for the voice recordings, overseen in New York by Jules Bass. Then the music, sound and voice tracks went back to Japan, alongside more change requests. It was standard for Arthur Rankin to visit Japan after this step, just before animation began.

In December 1979, Topcraft entered production on The Last Unicorn. The Japanese supervisors held meetings to get the team on the same page — and to give the necessary directions.

According to Topcraft, one of the main “themes” of the production was expressive acting in the character animation, leading the studio to bring in live actors as reference. Another focus was the impact of each overall shot: the design, the lighting, the layouts, the effects.

The art of Kay Nielsen influenced the forest backgrounds at the start — Kuroda claims that Topcraft invested 2 million yen into an artbook to study Nielsen’s work. The studio also created a clay model of King Haggard’s castle and took pictures of it under different colors of light, using them again as reference. Colored lights, and lighting effects in general, were seen by Topcraft as crucial to the film’s style. (One trick was to put small holes in the art and shine colored light from below.)

Animation was done through the so-called “first” and “second” key animation system. First, a small strikeforce of key animators rushed through the shots, drawing the poses simply and setting the timing. There were three on The Last Unicorn — including Tadakatsu Yoshida and Kazuyuki Kobayashi, who became key animators on Nausicaä.

A larger team supported them with “second key animation,” fixing and more fully drawing each shot. Six are credited, including Yoshiko Sasaki, Masahiro Yoshida and the previously mentioned Hidekazu Ohara. Those three later animated for Nausicaä, too, as did a couple of the in-betweeners credited on The Last Unicorn.9

The team drew according to the prerecorded voices (somewhat unusual in Japan at that time), using charts to help with lip sync — since the animators didn’t totally understand what was being said.

Another unusual step for Japan: the artists had to time each shot based on the voices and music. This made it so “drastic editing cannot be done like in domestic animation,” wrote director Katsuhisa Yamada. It was closer to the Disney style, but more restrictive, since the animation needed to sync with sound effects as well.

Production wrapped at Topcraft in September 1981. The figures vary regarding Rankin/Bass’s budget, but it was much cheaper than an average animated feature. Walker didn’t quite get his $5 million — the entire project cost closer to $3.5 million, and probably below that.

Arthur Rankin later said, “We should’ve had more money to make it; we could’ve made a better film — with more production. Not the script, but the depth of animation.” Even so, he was happy with the final result, calling it “a very good film.”

As for Beagle, his worries didn’t fully go away until he saw the finished film. When he spoke to the press about The Last Unicorn in 1980, the subject of the Rankin/Bass Hobbit came up. “This, please God, has to be a lot better,” Beagle said. He went on:

They’ve been very good about the script, and they’ve got good actors, not your typical cartoon voices. They’ve got Alan Arkin, Tammy Grimes, Christopher Lee, Jeff Bridges, Mia Farrow and Angela Lansbury. [...] They’ve been pressing for a good adult animated feature — and not aiming at the Frosty the Snowman market.10

When Rankin/Bass gave Beagle a private screening of The Last Unicorn in the early ‘80s, it had a surprising effect on him. As he’s said in recent years:

… I didn’t know how to react. I was so braced for the worst that I couldn’t take in the fact that it was actually a good film. It took several viewings before it finally hit me that they’d absolutely transcended themselves.

Today, Beagle considers it a classic. But not everyone was so thrilled with it back then. The curse of The Last Unicorn didn’t ruin the film, but it did sabotage its distribution.

Walker assumed that this step would be easy — he was shocked to learn that no one wanted to touch his project. Universal was set as the distributor but was reportedly “less than enthusiastic” about the final film. The Last Unicorn was dropped, and fallback companies proved elusive in Hollywood. Rankin/Bass got stuck with a tiny, low-budget distributor from Utah. The film opened in late 1982 and box office returns, Rankin said, were “not too good.”

But, again, The Last Unicorn found its fans over time. It developed a cult following in America and became a hit in Germany. Like The Secret of NIMH, it’s one of those left-field, lesser-known animated features from the early ‘80s that deeply affected the select group of people who saw it. Even now, it still sells on Blu-ray and DVD.

Plus, while The Last Unicorn wasn’t released in Japan, it had an impact on the local industry. Few Japanese studios were making theatrical animated features — most couldn’t. But Topcraft had done just that with The Last Unicorn. Its staff knew the process.

Nausicaä came to the studio in part for this reason. According to one scholar, the “choice of Topcraft was unavoidable because, apart from Toei, Topcraft was said to be one of the very few animation studios in Tokyo which had the infrastructure and experience to make a full animated feature during that period.” The result was an era-defining film. When Topcraft dissolved after Nausicaä, its president Toru Hara took charge of the newly formed Studio Ghibli.

It’s yet another unlikely wrinkle in the story of The Last Unicorn. From every angle, the film is an oddity. But it remains an essential piece of animation history — and, in its own strange way, a classic.

2: Newsbits

In its fourth weekend, Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse has reclaimed the top spot at the domestic box office, beating both Elemental and The Flash. It’s earned around $560 million worldwide, including roughly 329 million yuan (over $45 million) in China. Not included: Russia, where Spider-Verse hasn’t been released but remains the top film thanks to pirate screenings.

One project that will launch in Russia: How Do You Live, the next film by Hayao Miyazaki. Trade magazines say that Russian Report bought the distribution rights.

Speaking of How Do You Live, it premieres in Japan on July 14 — and theater locations have been revealed. While The Wind Rises screened in 343 Japanese theaters, this one will reach 386.

English director Jonathan Hodgson has a new short out, Margarita’s Story, based on an interview with a child who escaped from Mariupol in Ukraine.

One more Miyazaki-related story: researcher Fu Guangchao published a bunch of photos from Miyazaki and Isao Takahata’s visit to China in the early ‘80s.

Also in China, the so-called “Golden Monkey King Awards” took place in Hangzhou. It’s a big event — winners this year included Yao: Chinese Folktales (among series) and the short film Jie, part of Bilibili’s Capsules anthology.

In Mexico, a program to preserve local animation history is underway. Cartoon Brew has the story.

Lastly, we looked into Charlie Brown’s All Stars (1966), the underrated second Peanuts special.

Until next time!

From Michael Chase Walker’s 2022 interview with Traversing the Stars, the source for many of his quotes (and other details).

Beagle talked about the connection to A Charlie Brown Christmas in an interview with Toon Zone, another source we used a few times. The Balaban & Quine news was reported in the Los Angeles Times (March 6, 1972).

According to Kenneth J. Zahorski’s book Peter Beagle (1988), Walker read the novel in July 1974. An article in the Los Angeles Times (February 27, 1980), which we referenced a lot, reports that he bought the option on his birthday in May 1976.

Many of these details come from the magazine Crawdaddy (November 1978).

The deal figures come from a newspaper clipping (possibly from the Peoria Journal Star) on Walker’s personal site.

From the Blu-ray extra “Highlights from the Last Unicorn Worldwide Screening Tour with Peter S. Beagle.”

Beagle said this during the commentary track on the Last Unicorn Blu-ray release, a source for several details and quotes today.

From the Blu-ray extra True Magic: The Story of The Last Unicorn, another important source. Makoto Kuroda wrote a little about the storyboarding process here.

For those interested in a fuller staff list, see the one Kuroda posted here (in Japanese). One notable member of the in-betweening team was Takashi Watanabe, who became a prolific director (see: Boogiepop Phantom, Slayers). Another, background designer Minoru Nishida, was later the background supervisor for Princess Arete.

From the Democrat and Chronicle (April 24, 1980).

Wonderful article! I honestly only knew the broad strokes about how Rankin-Bass operated, and I appreciate knowing the context to what made this film hit so different. I'm so glad Beagle liked the film in the end.

Also fascinating to know this is what Topcraft did right before Nausicaa. Who knows what they'd have gone on to make if Miyazaki and his gang hadn't swooped in...

Fascinating behind-the-scenes dive! I'm surprised to hear the box office returns of The Lord of the Rings 1978 film be described as "mediocre" when it grossed over $32 million on a $4 million budget. The adaptation's critical response when it was released, however, could certainly be considered mediocre.