Happy Sunday! We’re here again with the Animation Obsessive newsletter, and this is the game plan:

1 — exploring a gorgeous, classic TV series from Hungary.

2 — animation news around the world.

3 — the week’s loose ends.

4 — retro Czech stop-motion.

New here? We publish Sundays and Thursdays. It’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues — get them right in your inbox each week:

All good? Let’s go!

1. ‘The essence of the bunny is love’

In early February, we got an email from a reader in Hungary. His question: what about an issue on Hungarian animation? We’ve covered cartoons from places like Croatia and (lately) even Slovakia. But we haven’t dedicated an issue to Hungary.

The idea was a good one. It’s been on the list since his email. Animation in Hungary has a particularly vibrant history — enough to fill dozens of issues of our newsletter. There’s so much, it can feel almost daunting. Luckily, there are entry points. One of them is The Rabbit with Checkered Ears.

This is a TV series from the mid-1970s — but you might recognize it from the internet. We’ve shared it before, and accounts like Eastern Cartoons Out of Context have spread it even further. People online really seem to love it.

What’s so odd, and so impressive, is that people had the same reaction in the ‘70s. This story of a flying rabbit that helps children has always had a certain magnetism, a universal appeal. After sweeping Hungary, The Rabbit with Checkered Ears aired in almost a hundred other countries. It’s a special show that’s worth taking a deeper look at.

In the creation of The Rabbit with Checkered Ears, two names stand out above all others. These are writer Veronika Marék and the late director Zsolt Richly. Marék is a successful children’s author — Richly was a bright light among the animators at Pannonia Film Studio in Budapest. Both were essential to the series.

Their partnership began outside animation, though. “I met Veronika Marék for the first time in the sixties, in the editorial office of Kisdobos children’s magazine,” Richly recalled. Both of them were artists for the publication, and each admired the other’s work. Marék described Richly as “a kindred spirit in every way.”

In 1966, Richly joined Pannonia. Hungary was communist at the time, and the studio received state funding to make artful, adventurous cartoons. One that Richly created, Suite (1968), was reportedly the first Pannonia film to turn “folk [art] motives into fine art symbols.”1

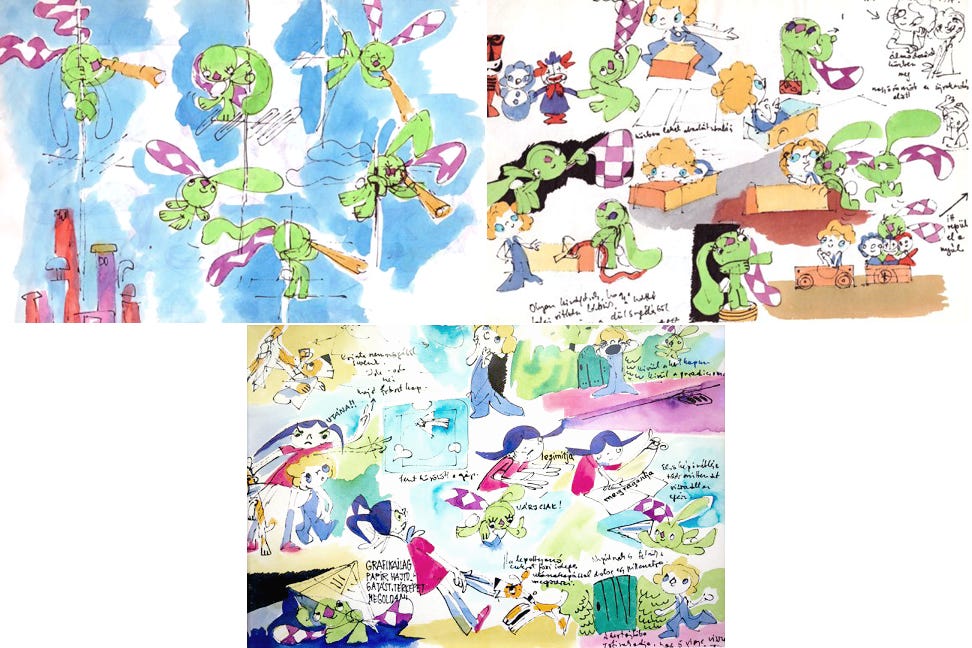

As Richly rose through the ranks, Marék joined him to write a series pilot called A Little Car With Seven Dots (1973). It looks similar to The Rabbit with Checkered Ears — Richly dubbed it “preparational work” for the show. And that’s what happened next.

At that time, a manager from Hungarian Television asked Marék to submit a TV pitch. “The figure of the rabbit popped into my head,” she said — a character with oversized ears that it tripped over and dragged around. Eventually, the rabbit would learn that its ears allowed it to fly and help people. (“I didn’t know of Dumbo yet,” Marék noted.)

Her concept, complete with her black-and-white sketches, was approved for 13 episodes.

Richly was appointed to lead The Rabbit with Checkered Ears, co-creating the series with Marék and developing her idea. They were creative partners. Richly later said:

I went to work meetings in their apartment overlooking the Danube and Bem Square. She invented our hero of a puppy-like bunny with checkered ears. For several years, she [wrote] the stories, and I tried to conceive her ideas as a series of pictures and films.

The show’s pop-art aesthetic derived not just from A Little Car, but from the work that Marék and especially Richly had done for children’s magazines. It’s instantly charming. Richly came up with the rabbit’s final appearance, and with the idea of having its ears spin like helicopter blades.

For the stories, Richly said that they made sure to include a “hidden pedagogical sense” in the series, alongside the fun. Good always triumphs over bad. The rabbit is “a kind of modern guardian angel,” Richly explained. He and Marék agreed that “the essence of the bunny is love.”

Production of The Rabbit with Checkered Ears was a several-year affair. Here’s Marék in retrospect:

There was a big wooden cabin in the yard of Pannonia Film Studio; that was Zsolt Richly’s workspace. And there were a lot of girls and boys who drew and painted. And what was finished, they took and photographed. Most interesting, I must say, was that these episodes were made without words. So it took a story that didn’t require speech. This was very challenging. [...] On the other hand, the action came to life with the music of a brilliant composer, Árpád Balázs. These three elements worked [in tandem]: fairy tale, image and music. And it was from these three elements that the Checkered Ears story came together.

After wrapping the first episode, Pannonia’s managers weren’t sure about the series, according to Marék. They felt that it was “too fast” and that children would be confused by the “quickly alternating events and pictures.” The project’s survival was on the line.

“We went to a school then and screened an episode,” she said. The kids, a younger generation accustomed to the pace of TV, completely got it. Pannonia came to agree that things had changed since the old days, and the series continued.

That early screening was a preview of things to come.

It’s tough to overstate the success of this show in Hungary. As the site Origo put it in 2008, “There is hardly a Hungarian over the age of thirty who does not have at least some vague memory of The Rabbit with Checkered Ears.”

But it wasn’t obvious at first. “I didn’t really feel it,” Marék said. Pannonia ordered another 13 episodes, but the show lacked the markers of popularity familiar in the West. In the beginning, there wasn’t even merchandise.

It got clearer what they had when foreign markets began to respond in a big way. As a wordless series, it was ready-made for exporting. It even aired in the United States — as a segment on Nickelodeon’s Pinwheel program. Once merchandise did start to appear in Hungary, Marék remembered being stunned by the scale of it:

My lord! What a quantity appeared, from gas stations to toy stores, and everyone bought it and took it. Incredible scenes we saw. For example, we went to Lake Balaton and a motorbike went in front of us, and strapped behind the driver was a bunny with checkered ears. As he rode, the bunny’s huge ears floated behind him. Well, that made us burst out laughing. We have had and still have many, many such experiences.

In the end, The Rabbit with Checkered Ears was a career-defining hit for Marék. She said that it helped her to achieve a “big dream of [her] life” — breaking into cartoons.

If the show was defining for Marék, though, it was even more defining for Richly. He was an important figure in Hungarian animation, working on films like Son of the White Mare (1981), but his name is forever tied to this series. His other work is so overshadowed that it’s sometimes credited to the wrong artists and directors.

His view on being known for The Rabbit with Checkered Ears? “I take this as an honor,” he said in 2002. The miscrediting of his other work didn’t bother him — and neither did being pigeonholed as a children’s director. As Richly remarked, “There is no more grateful and sincere audience than children.”

2. Newsbits

In China, the Anim-Babblers team is still rounding up graduation films. There’s a really impressive batch of images and trailers from the China Academy of Art this week.

Meanwhile, China’s government has introduced an “Online Label” for streaming dramas. Unless a project receives one from a state review board, it can’t move forward. What does this mean for animation? Time will tell.

The week’s most disconcerting short is Edgar’s Butterquiet Tulpa from A Studio Digital in America. Jonni Phillips (Barber Westchester) wrote, directed and animated it.

Also in America: union victories. Now voting to join The Animation Guild are production staffers from Family Guy, American Dad and The Simpsons.

Jujutsu Kaisen 0 wrapped up its theatrical run in Japan as the country’s 14th-highest-earning movie to date.

In China and Russia, International Children’s Day (June 1) was big at the box office. Animated films topped the charts in both countries — Doraemon: Nobita’s Little Star Wars 2021 for China and the new Kid-E-Cats movie for Russia.

Another from America — Coleen Baik, who writes The Line Between, compiled an uber-detailed article for UX Collective about the making of her latest film. Whether you’re trying to learn or just interested in process, don’t miss this.

In Italy, the island of Sicily has a new plan for growth: partial state funding for film, TV and documentary projects, both live-action and animated.

What’s in My Head talked to American exec Linda Simensky about Cartoon Network, “UPA revival” and more. “Outstanding interview with one of the best executives I’ve ever worked with,” tweeted Craig McCracken.

We took a visual tour of Slovakia’s most iconic animator — a very different kind of experience for us, which we liked a lot.

Lastly, while unveiling a Looney Tunes NFT series with a rushed-looking promo image, Warner gave us the week’s scariest corporate spiel:

… these beloved characters continue to spark nostalgia and excitement across all generations. Today, as digital engagement and technology evolves, the Looney Tunes collection will further expand the reach of the franchise, bringing fans together from around the world, offering unique experiences, community building, storytelling, and a whole new way for them to engage.

3. Loose ends

Hope you’re enjoying today’s issue! Thanks for giving it a look.

Before we continue, we want to acknowledge a few words written about us. This week, Gizmodo called our piece on Chinese ink-wash animation “incredible” and “well worth checking out.” Writer Linda Codega has our thanks. There were also the remarks from No Film School we mentioned on Thursday. We appreciate those, too.

Shout-outs aside, we cover The Lion and the Song below — a beautiful work of Czech puppet animation from 1959. The story behind it comes from Animation and Time, a book we had to import from Czechia.

This section is for members (paying subscribers). If that’s you, read on. To everyone else — we’ll see you next week!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Animation Obsessive to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.