Happy Sunday! The Animation Obsessive newsletter is back from its mid-year break. We want to thank everyone for their patience as we’ve relaxed and prepared for the second half of 2024. There’s a lot in store from here. (And welcome to the almost 2,000 people who’ve signed up since we’ve been gone!)

With that, here’s our lineup for today:

1) How the first Lupin the 3rd TV series came to be.

2) The recent news in animation.

Now, let’s go!

1 – Accidents of history

Even if you haven’t watched it, you’re probably aware of Lupin the 3rd.

The franchise has existed for close to 60 years — across comics, TV, movies and so on. Its impact is inescapable. Hayao Miyazaki debuted as a movie director through Lupin (with The Castle of Cagliostro, 1979), and many more continue to touch it. Before Godzilla Minus One, director Takashi Yamazaki made his own acclaimed Lupin film.

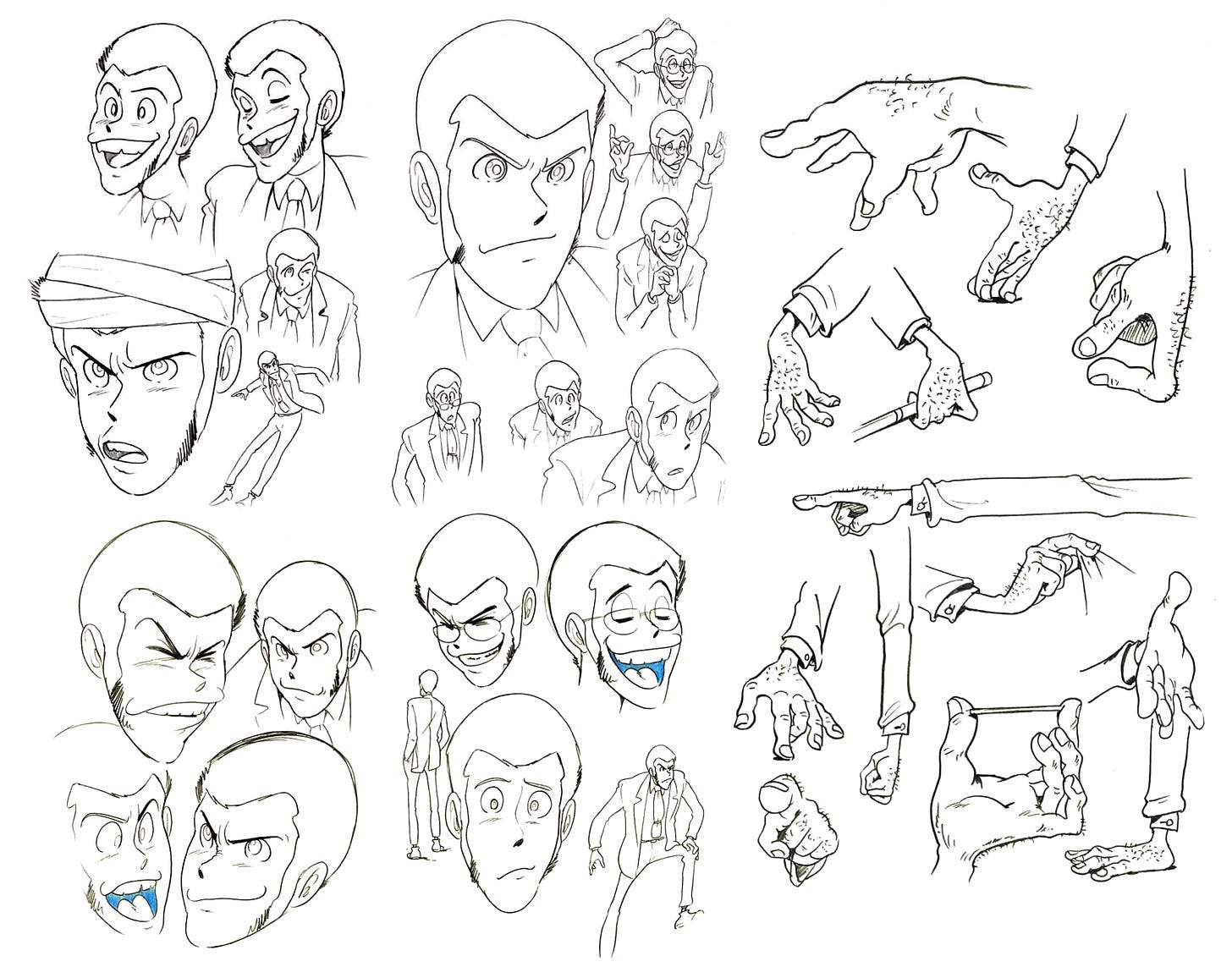

The whole idea of Lupin the 3rd links back to Japan during the ‘60s and ‘70s — the birthplace of these characters. Lupin is a playboy thief who drives a Fiat 500, pulling heists with his allies Jigen (a gunman) and Goemon (a swordfighter out of time). Fujiko, a femme fatale, complicates things. The hapless Inspector Zenigata gives chase to them all.

Within that framework, though, are variations. Lupin is an unstable character, never exactly the same twice. In the words of manga creator Naoki Urasawa (Monster), “I actually feel there are completely different Lupins: the original manga character, the Miyazaki character and any subsequent series, they’re just different people.”

Still, Urasawa does believe in a true version of the character. “The real Lupin for me,” he went on, “is the one that was created by Miyazaki.”

He wasn’t talking about Cagliostro. Urasawa was going further back — to the original Lupin TV show from the early ‘70s. At first, it was a flop. A young Miyazaki arrived with Isao Takahata to fix it. The result was a chaotic series at war with itself. Yet its mishmash of styles and tones helped (some argue) to make it a hit.

But many things happened before Miyazaki and Takahata entered the picture. Lupin, as we recognize it, started at a racetrack.

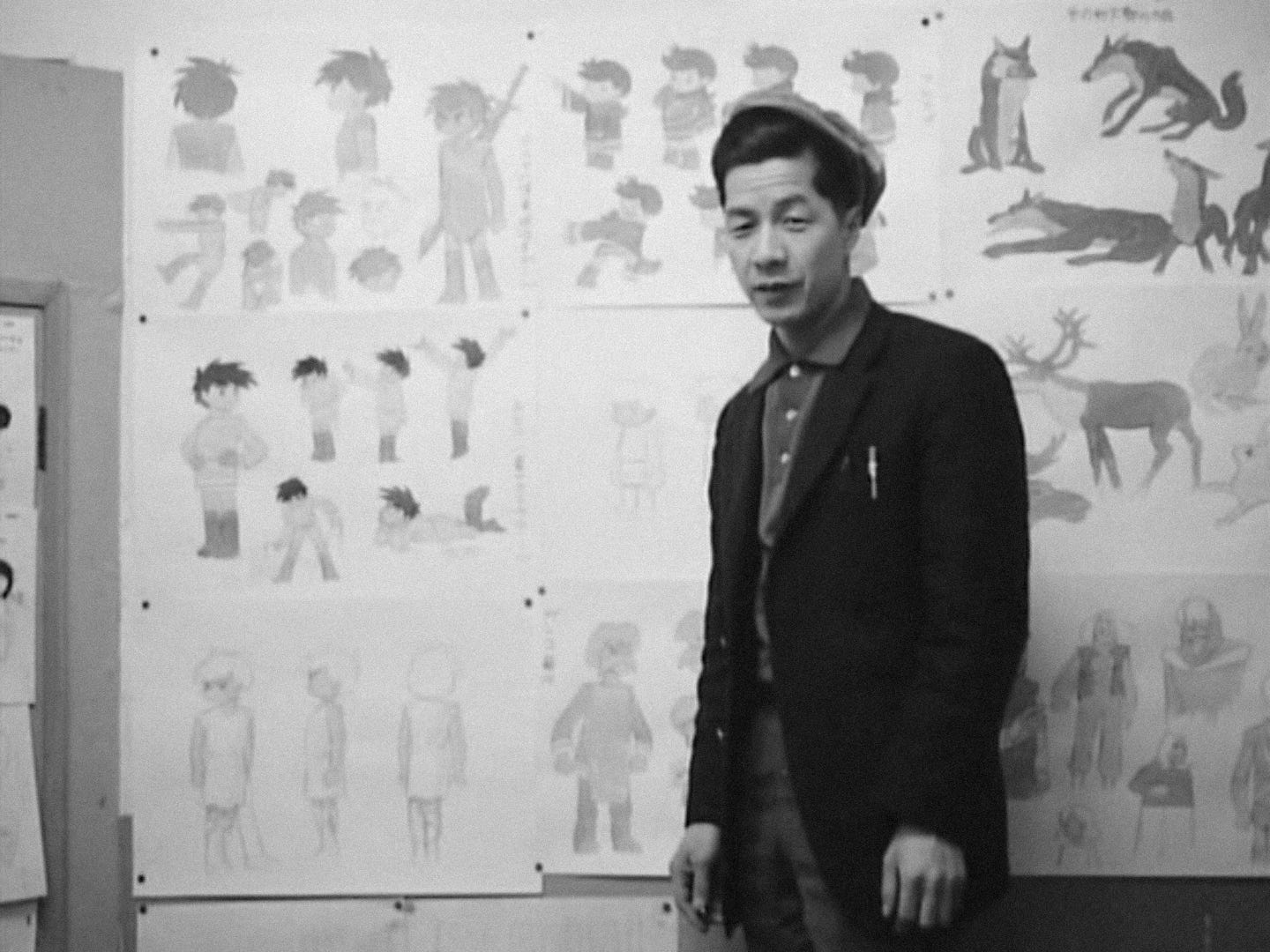

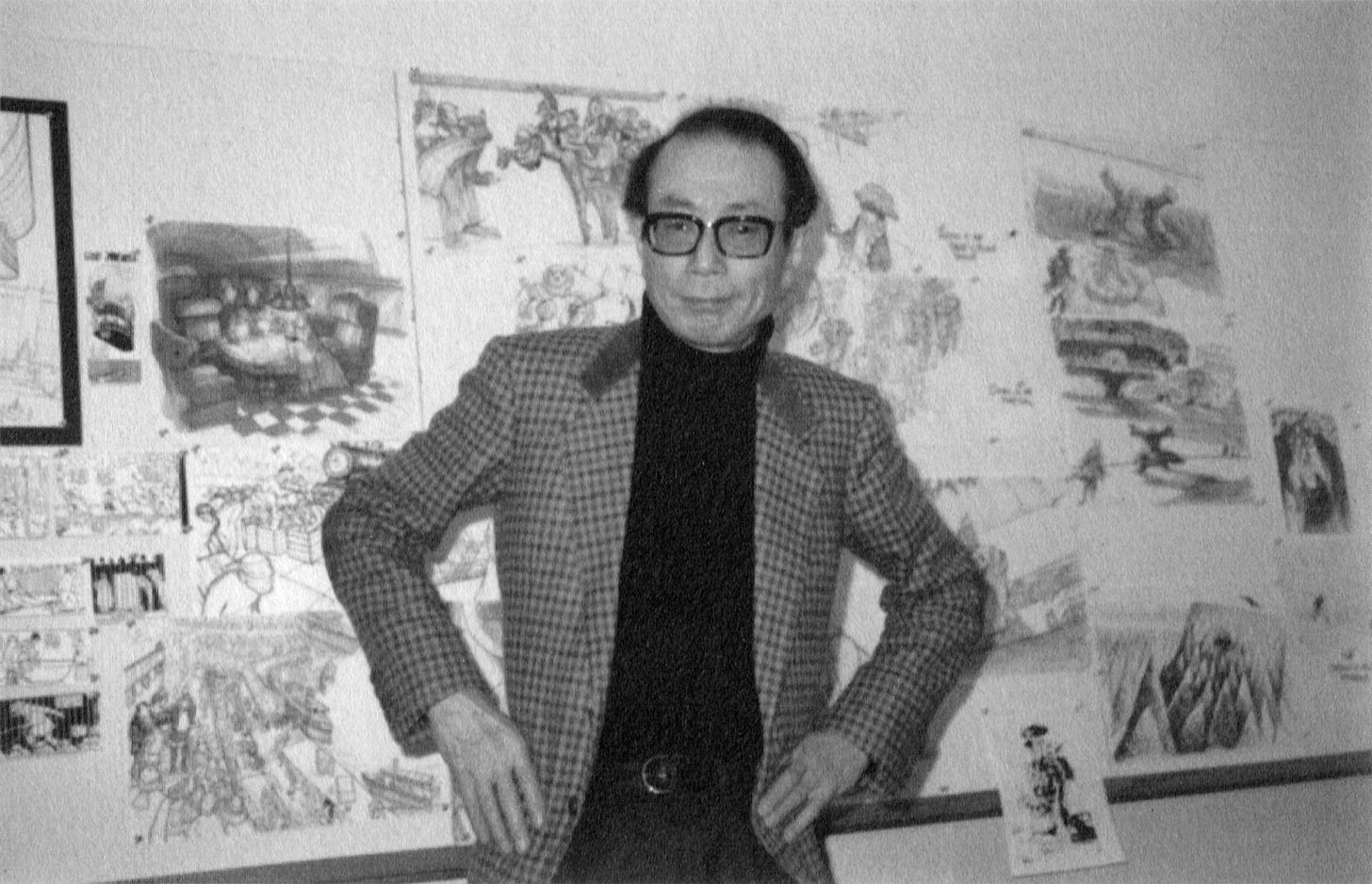

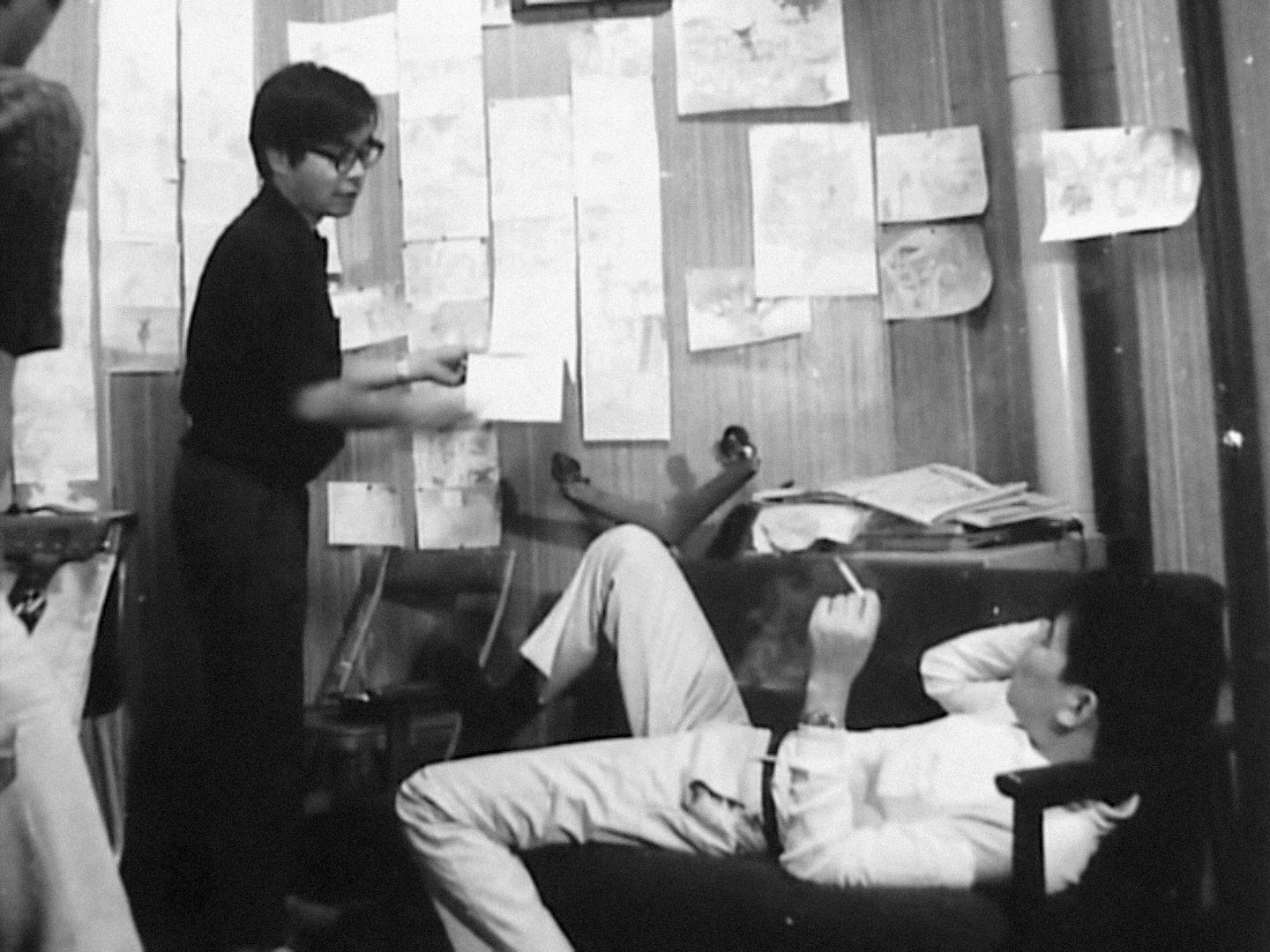

In the late ‘60s, an artist named Yasuo Otsuka liked to watch the car races in Funabashi. They were messy, wild events. He remembered standing at the most harrowing part of the track to see the drivers “spin and crash.” These races were maybe an hour’s drive from Tokyo, where Otsuka worked at Toei Doga — the central animation studio in Japan.1

Otsuka was Miyazaki’s mentor at Toei. He’d been with the team since the ‘50s — a union man, a car fanatic and arguably Tokyo’s best animator. “Otsuka taught me all about motion. That’s the heart of animation,” Miyazaki once said.2

But there was discontent at Toei Doga. The ambitions of the staff clashed with the conservatism of the company leadership. And, at the races, Otsuka met a man in sunglasses who would steal him away from the studio.

Otsuka viewed that man, Yutaka Fujioka, as “a little suspicious.”3 They kept running into each other at the Funabashi track, allegedly by chance. Fujioka was middle-aged and spoke like a hustler. Over time, he slipped animation talk into their conversations. What if, he said, cars could be portrayed more accurately in animation? What if Japan could make animation for adults?

After several meetings, Fujioka got more specific. He pitched Lupin the 3rd.

In reality, he’d been scouting Otsuka. Fujioka ran a studio called Tokyo Movie that did animation for Japanese TV. The edgy Lupin comics were popular — Fujioka wanted to adapt them into a feature film. For that, he needed Otsuka. Fujioka hired talents who matched the vibe of a given project. Otsuka was a bit of a rambler, a street racer, a drunk driver and a casual expert at his craft. He fit.4

“I sensed some potential in the project,” Otsuka recalled. And so he quit Toei, with its salarymen managers, to join the questionable guy in sunglasses.

Otsuka landed himself at A Production, Tokyo Movie’s partner studio, where a pilot film for Lupin was taking shape.

The company had plenty of former Toei people — one of them ran it. But overseeing the pilot was an “anti-authority” and vocally “anti-Toei” rebel, Otsuka said. This was Masaaki Osumi, originally from the world of puppet theater. Osumi wasn’t a visual artist and didn’t storyboard, but he knew how to define a project. As Otsuka put it:

Osumi-san uses a lot of words. It’s like this, it’s like that, this is interesting, this is fun. I was amazed by his ability to persuade storyboarders and animators with so many words.

They and the team developed the style of the Lupin comics to suit animation. The source material was violent and fairly seedy — and so was the pilot. It was aimed at adults, which proved to be a curse.

Even with a 12-minute proof-of-concept in hand, production studios didn’t want to take the risk. Otsuka wrote that negotiations got “stuck in the mud.”

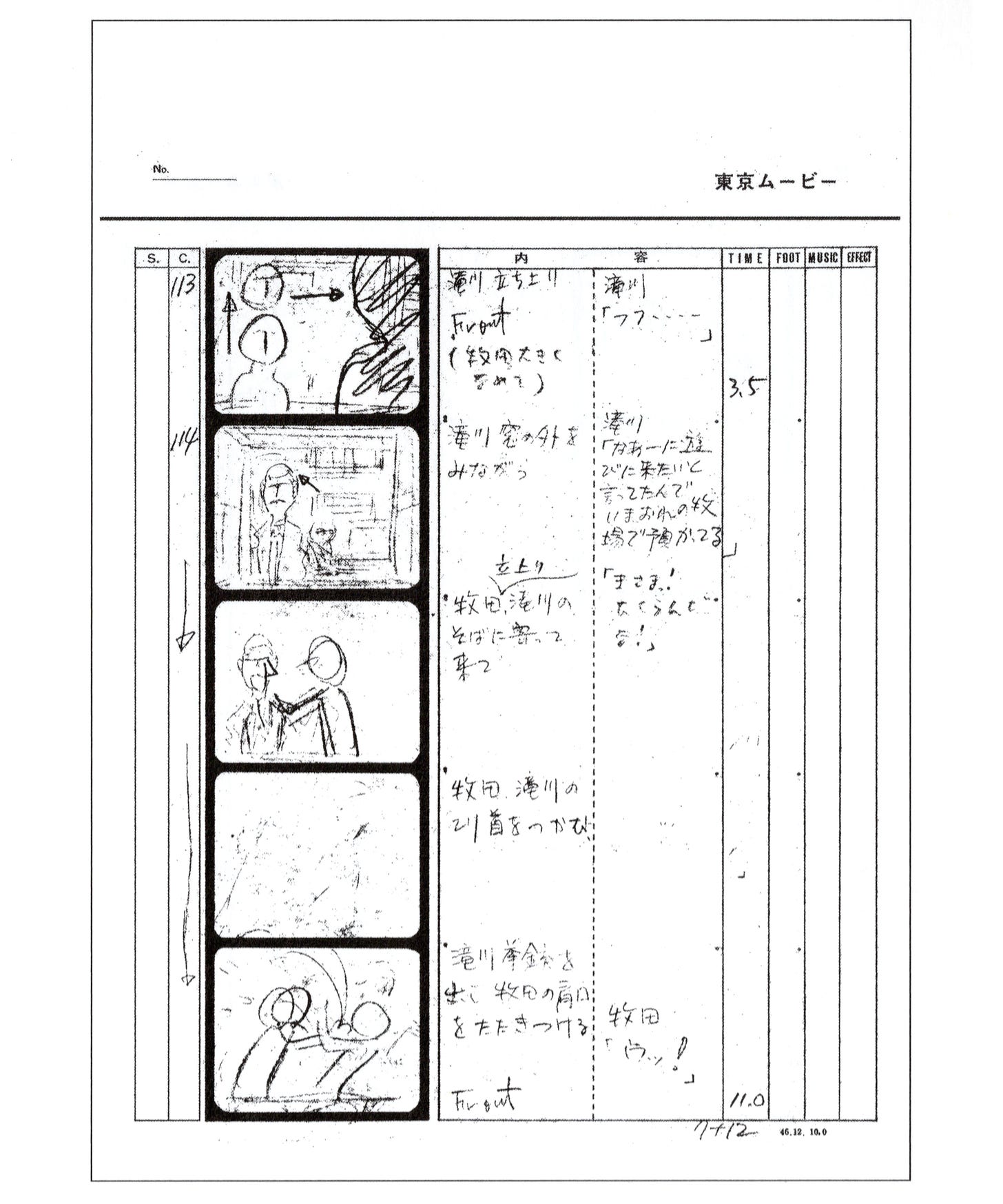

Over a year later, in the early ‘70s, the Lupin project was reborn for television. Adult animation on TV was a gamble. But Yomiuri TV, headquartered in Osaka, signed off on the proposal and backed the show. Osumi was the director, with Otsuka overseeing the animation and design.

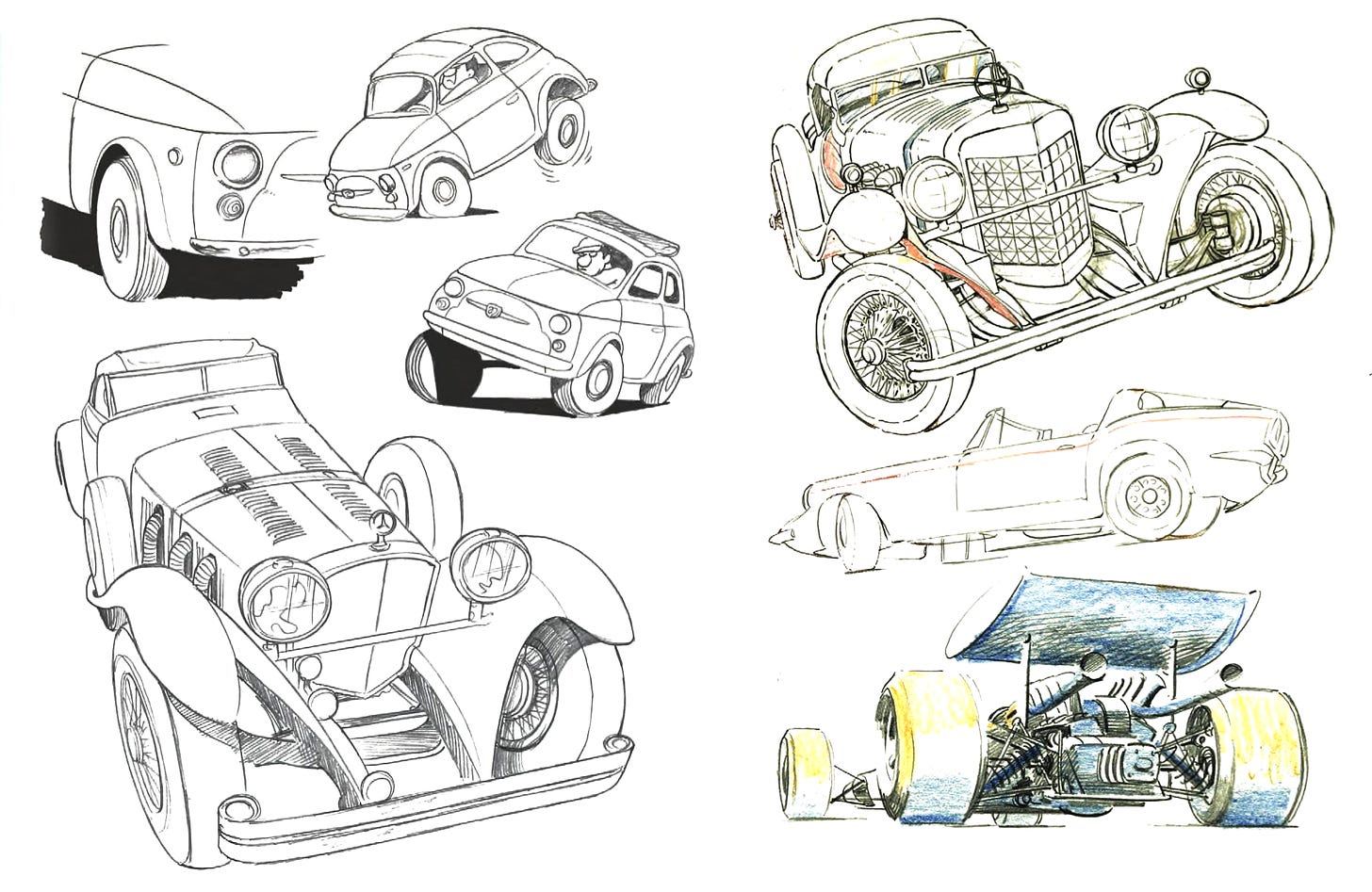

Part of their proposal was the realistic depiction of objects, from cars to guns to watches.5 Each one needed a specific make and model. This stuff was a lifelong obsession of Otsuka’s, and one of his big contributions to the series. “What appealed to me about Lupin, what got me attached,” Otsuka later wrote, “was that it was a vessel I could pour my interest in things like cars and guns into by animating them.”

As he said elsewhere:

At the time that we started making the first TV series, when they drew a car in animation, it looked more like a matchbox than a car. We could not tell if it was a Toyota Crown or Nissan Bluebird. So we decided to put certain identities to the cars. We started adding extra details and drawing them apart. For example, like he is driving a Mercedes-Benz.

Before too long, Otsuka was convinced that Lupin would be huge — a groundbreaking new hit.

Tonally, Osumi’s keyword for Lupin was “ennui.” He felt a cynical, decadent, world-weary attitude in the comics. “To me,” he said, “Lupin may appear to be slapstick, but at its core it’s like a hard-boiled novel or film noir.”

He wanted a “live-action feel,” drawing ideas from the traditional movie world. He also stretched the show’s limited budget: with Eisenstein’s montage theory in mind, he used editing to make still shots and quick cuts feel impactful.6

Under Osumi’s guidance, the Lupin show had jokes, but it also went grim and lurid. Otsuka noted his own reservations with the “nihilism” of one episode, and said of others, “I wasn’t really in favor of the salacious parts [laughs]. They were just necessary for the direction, so I had to draw them.”

Lupin was meant to air at 9 p.m. for 17- or 18-year-olds. According to Otsuka, the show was billed as “seinen manga,” or a young adult cartoon.7 Yet the broadcaster made mistakes. Marketing Lupin was tough — and, for some reason, the series was moved to a child-friendly slot earlier in the evening.

When it reached the air in late 1971, it was an immediate dud. Otsuka called the ratings “absolutely abysmal” by animation standards. Osumi’s past show Obake no Q-Taro (1965–1967) had been a major success, with viewership above 30%. The first Lupin episodes went as low as 4%.

Yomiuri TV, previously all for this “adult animation” idea, laid the blame on the animation studio. After a few episodes, Yutaka Fujioka and Osumi got pulled into a meeting and torn to shreds. They were told to redo Lupin for kids, to cut the racy stuff. For effect, Fujioka purposely bowed so hard that he smashed his head into a desk.

The whole thing was a kind of betrayal, and a humiliating one. After a bad meeting in Osaka with Yomiuri TV, Osumi told Fujioka that he was quitting Lupin. He didn’t go back to the studio, even to clear his desk.8 From there, Osumi left animation for a few years — and refused to speak publicly about the series for many more. “I can’t forget the sense of isolation and loneliness I felt at that time,” he said decades later.

Lupin hadn’t even been airing for two months, but it was now leaderless. Many episodes were in production and the deadlines weren’t going away. Someone had to take over. The fallbacks were Isao Takahata and Hayao Miyazaki.

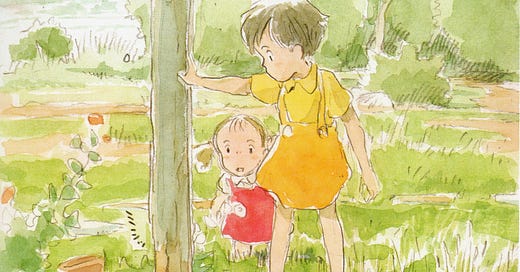

By this point, Takahata and Miyazaki were at A Production themselves. They’d joined to make Pippi Longstocking, and Miyazaki had traveled to Sweden with Fujioka to secure the rights — and failed. Their show was now dead, but they needed to keep working.

Even so, Lupin didn’t really appeal to them. Otsuka (who’d chosen to stay) remembered that Takahata and Miyazaki were “distinctly negative” about the series, from its use of “sex appeal” in a children’s timeslot to its thief protagonist. Taking over another director’s show was an uncomfortable prospect, too.

But there was something here. Miyazaki enjoyed the “overwhelming energy and hungry spirit” of the Lupin comics. Takahata wrote that the subversive, jokey part of these characters appealed to them — as people who “hated” the ultra-serious, “cool” heroes of animation back then.9 They also didn’t have much of a choice.

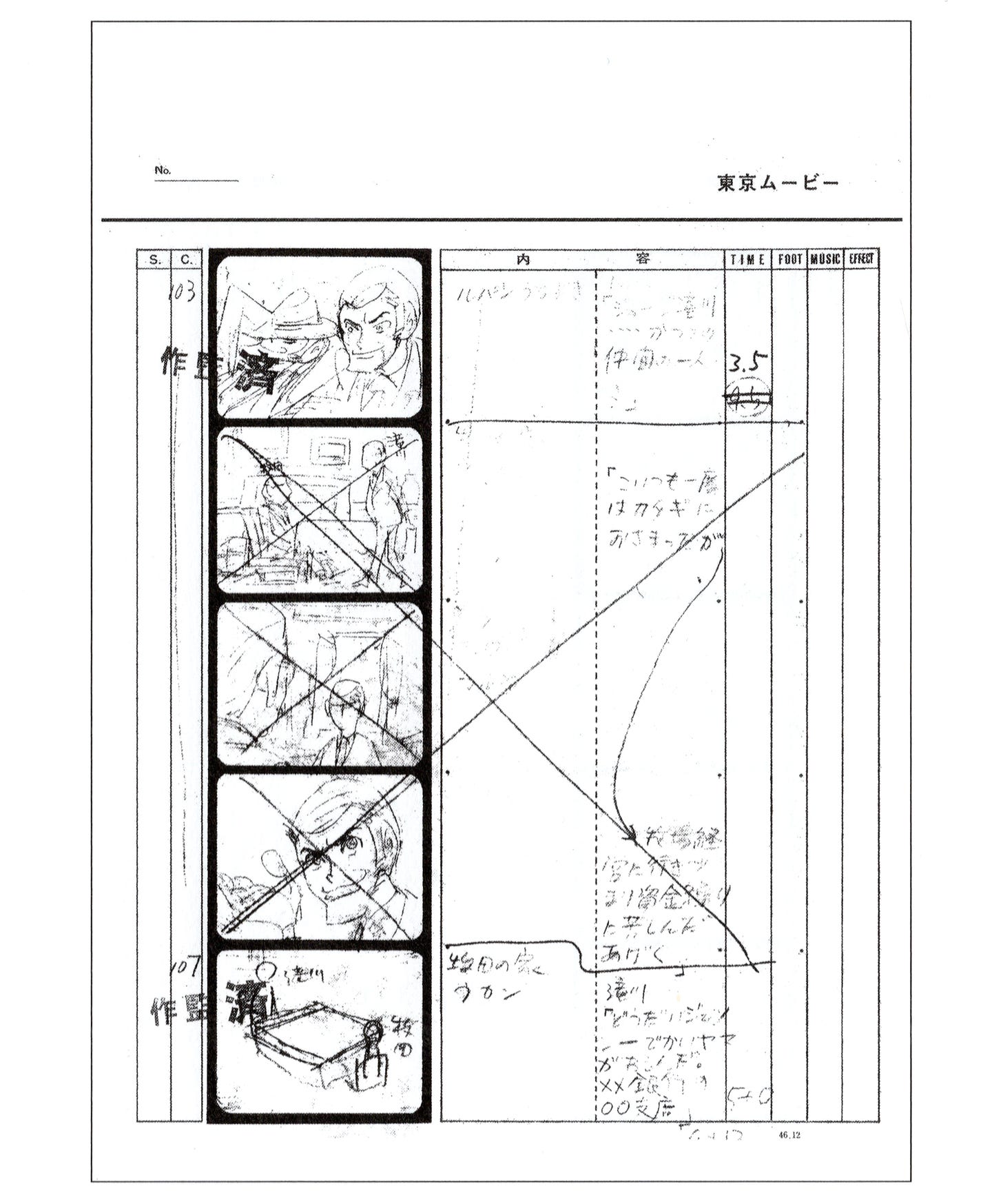

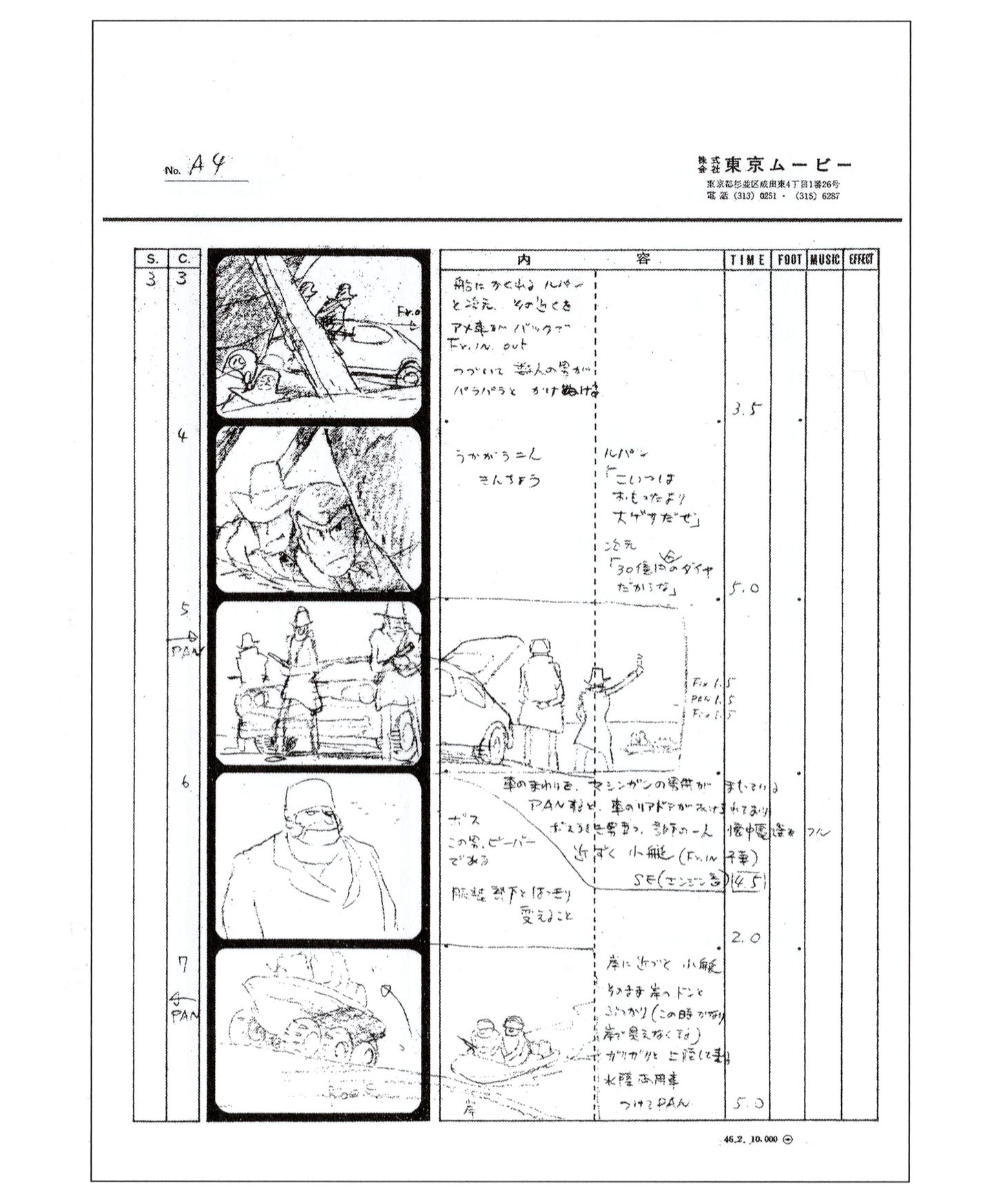

In the end, they took the job. As requested, Takahata and Miyazaki would rework Lupin into a children’s series — editing and completing the unaired material made under Osumi, and adding their own. They required their names to be omitted (the credit went to the “A Production Directing Group”). From episode five, their changes began to appear in fits and starts.10

Osumi’s ennui was among the first things to go. As Miyazaki wrote:

Lupin was conceived as a character who had inherited a fabulous fortune from his grandfather, who lived in a mansion, who didn’t participate in society’s materialistic rat race, and who — to ward off boredom (or ennui, as we called it) — occasionally worked as a thief. … Unlike traditional heroes, who would grin and bear whatever hardships they faced, Lupin took full advantage of a bountiful consumer society and was truly a creature of his era.

… [W]e were compelled from somewhere in the organization to make changes in the direction of the old Lupin series. We (Takahata and I) were in a fix, having taken over direction midstream, and wanting more than anything else to get rid of this sense of apathy that infused the story. We weren’t ordered to do so. … [Now] Lupin would be happy-go-lucky, upbeat and the son of a poor man. All his grandfather’s riches had been squandered, nothing was left. Lupin would run around in circles, always escaping and always pursued by the drone-beetle-like Inspector Zenigata. He would have a Walther P38 that had been mass produced by the millions and he wouldn’t make a big deal about it. He would rely solely on his wits and his physical abilities, and relentlessly pursue his goals. Jigen would be a friendly, cheery fellow, Goemon would be an anachronism and funny, and Fujiko wouldn’t advertise her cheap eroticism.

The old Lupin drove a Mercedes-Benz SSK, which was hard to draw and represented luxury. Miyazaki swapped it for a more everyday Fiat 500 — like the one Otsuka owned. That car was no trouble to draw and it suited this underdog hero. After all, TV regulations forced Lupin’s heists to fail by the end of each episode: he had no income.

Fujiko received one of the larger overhauls. Her hair was shortened to make it easier to draw — plus, she was no longer a sex symbol. (Years later, Miyazaki argued that some misunderstand Fujiko as having a “cheap, Cabaret London-style sex appeal,” when this is just one aspect of her character that she uses against shallow people.)11

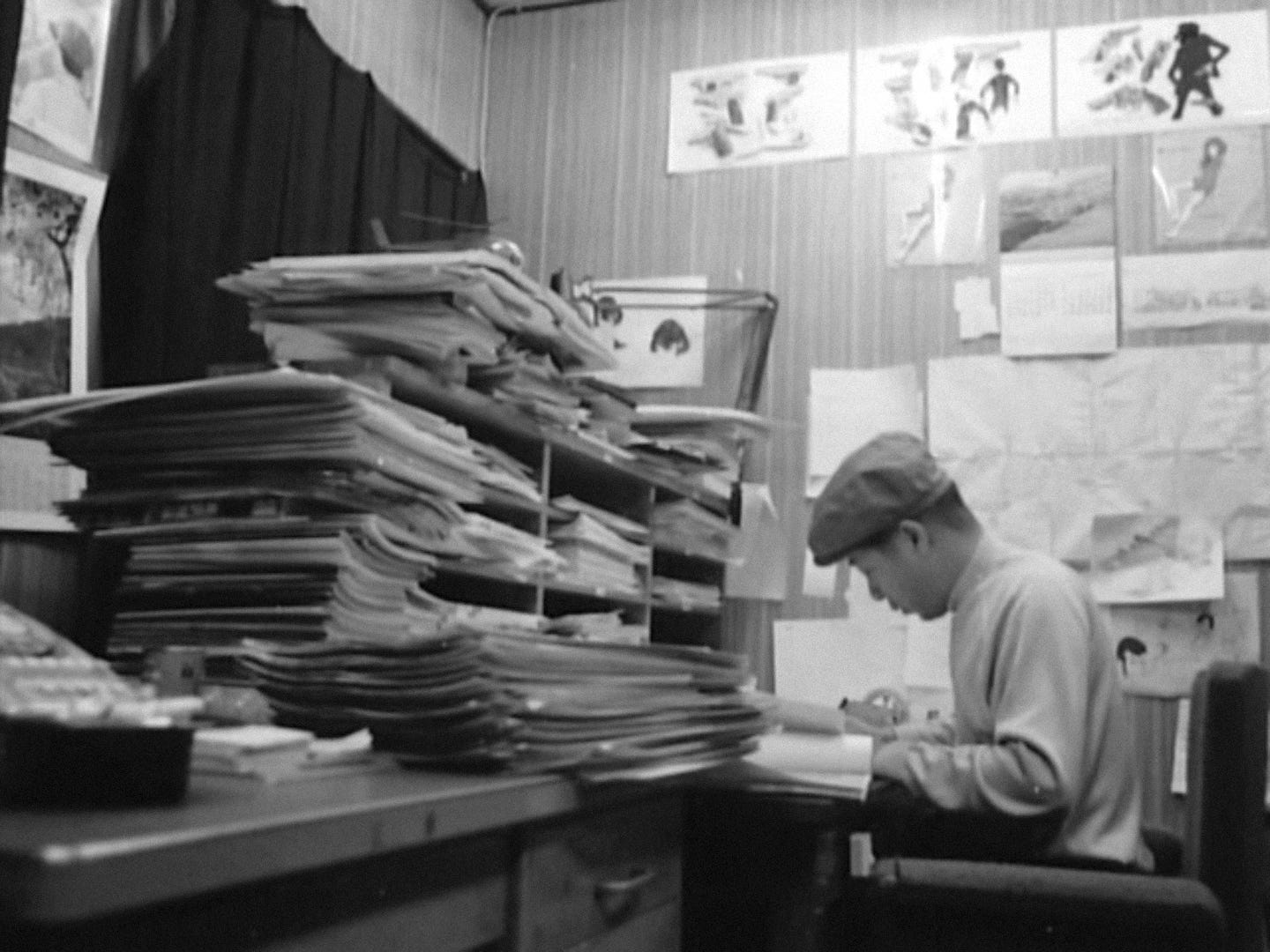

After the regime change, Miyazaki became Lupin’s new idea guy, bringing his endless energy to the project. Animator Toshitsugu Saida remembered him as an amazing presence, “always drawing something.”12

Miyazaki touched a little of everything: storyboards, designs, key animation. His new boards were detailed enough that the other animators often copied them closely, almost like layouts. As for Takahata, his part was more structural — cutting and rearranging stories into strong new arcs. He appears to have sketched boards of his own, too.

But, thanks to the change in direction, this was difficult work. Miyazaki said it happened at a “maddeningly hectic pace” — and the results often came out rough. Episodes got outsourced in chunks to many different studios to save time. Otsuka had to leave many drawings uncorrected. There’s great cartooning here, but, as Miyazaki noted, “In terms of technical achievement, there isn’t much to boast about.”

Miyazaki and Takahata left episodes as-was, too. There wasn’t time to retool Osumi’s vision for Lupin from the ground up. After the changes to episode five, for example, episode six went out mostly unedited. The rest of the series became a patchwork: sometimes new, sometimes partly redone, sometimes almost unchanged. Characters switched design and personality between episodes. The tone seesawed.

Even deep into the series, Osumi-era ideas stayed in effect. He’d worked a lot with storyboarder Osamu Dezaki (Ashita no Joe) before the changeover, and Dezaki’s own style was allowed to get into the show. You see it as late as episode 17 — where Dezaki illustrated a party with his famous still images. It doesn’t really fit the Miyazaki-Takahata approach, but it’s here anyway.13 A show came into existence that no one would’ve made on purpose.

Despite the chaos, a number of episodes turned out really well: fun, funny and solidly directed. Takahata highlighted 15 and 21 — from the story structures to “Miyazaki’s brilliant ideas and dense gag action.” For the former, Let’s Catch Lupin and Go to Europe, Miyazaki pulled from his own trip to Sweden.

In so many words, Miyazaki, Otsuka and Takahata were doing whatever they could and whatever they wanted. “We didn’t worry about the details,” Miyazaki said. The project was fun — even a “blast,” as both he and Otsuka put it. But it wasn’t the dream project that the Pippi series had been. Lupin was a job, and a messy one.

As Takahata said, “There are some stories that we were able to make reasonably interesting with our own ideas, but, to be honest, there were also episodes where we just had to give up and didn’t want to take responsibility.”14

The Lupin production shambled from 1971 into 1972 as a different show, just like Yomiuri TV had demanded. Yet its ratings weren’t going up. Episode 11, about a bridge bomber, aired January 2 after a crunch through New Year’s. The story is good and has a lot of Takahata and Miyazaki in it. Viewership, Miyazaki remembered, was “2–3%.”

And the animation studios were suffering. Otsuka said that one, JAB, was forced to close because of Lupin. Another, Oh! Production, came near to bankruptcy after the series. The strain of the whole thing meant that A Production couldn’t complete more than 23 episodes — three fewer than normal for television. Lupin imploded, and so it ended in March 1972.

According to Otsuka, there was a wrap party at Yomiuri TV without Osumi, Miyazaki or Takahata present. An executive there remarked, more or less, that you can’t win them all. Miyazaki described another party where Fujioka “essentially declared defeat and apologized at length to the production staff.”

The team moved on. Soon enough, Otsuka joined Miyazaki and Takahata on Panda! Go, Panda! (1972), made with the leftovers of the Pippi idea. After that, Takahata would direct Heidi (1974) at another studio, with Miyazaki on staff. That show was an era-defining megahit — and Lupin, for them, was just a footnote. An uncredited cleanup job.

But this wasn’t the show’s end. In the years after Lupin’s failed release, it picked up speed via reruns. Like Otsuka explained in 2003:

… the more it was rebroadcast, the more praise it got, becoming increasingly more popular. Some factors there were, perhaps, the short, 23-episode length, a handy size that let local stations use it as filler, and that, thanks to the low ratings, the broadcast fees were cheap. Local stations are still airing reruns, even now.

Sequels began to appear. The animated Lupin turned into a phenomenon — one that continues today.

For Takahata and Miyazaki, this thing wasn’t supposed to matter, but it clung to them. Miyazaki especially couldn’t escape it — and he directed The Castle of Cagliostro despite calling Lupin “a bit old and dated” by then. Pippi hadn’t happened and Panda! Go, Panda! had come and gone, but Miyazaki’s Lupin work became legendary among animation fans. It was an accident that, for years, was defining for him.

It was defining for Lupin, too. The show’s incoherence was another accident, but Takahata, Miyazaki and Otsuka all came to believe that it was a key to its success. Lupin’s split identity intrigued people. The Mercedes-Benz SSK and Fiat 500 versions of the character, Miyazaki wrote, were “like opposites in the series; they competed with each other, influenced each other, and as a result helped enliven the series.”

To viewers on the outside, Lupin the 3rd had arrived as a whole piece. Its production story wasn’t widely known until much later. This unstable Lupin wasn’t meant to exist, but he was presented without explanation as the real Lupin. And, in a sense, he was.

2 – Newsbits

We lost a legend of animation, Yan Shanchun (90). He worked at Shanghai Animation Film Studio on classics like Uproar in Heaven (1961–1964) and later co-directed Feeling from Mountain and Water (1988).

Well into its fourth season, the Indian cartoon Lamput remains one of the world’s best and funniest. Check out the recent episode Strength Potion on YouTube.

Also in India, Eeksaurus has a teaser for its new film Unicorn Lady, a traditional 2D project.

In Japan, columnist Tadashi Sudo looked into the rise of anime remakes — like the upcoming one for Ranma ½. It’s a trend caused in part, he wrote, by the need to stand out to viewers (including those abroad who remember these shows).

Historian Devon Baxter shared a rare short, One Wonderful Girl (c. 1956–1957), by the American studio UPA. It’s very fun, and new to us. See it on YouTube.

The Amazing Digital Circus, produced in Australia, is a YouTube indie series that draws more views than most things on Netflix. Now, it’s getting a retail toy line.

Inside Out 2 is the biggest-ever animated hit in Kazakhstan, both in box office and theater attendance. (Worldwide, it’s in second place behind the Lion King remake.)

Released in mid-July, the Chinese feature Into the Mortal World has gotten good reviews and a strong Douban score of 7.8. But it’s been a serious flop at the box office, attributed to its low number of screenings. See the trailer here.

Two months later, the music video for the Japanese song Hai Yorokonde continues to be a viral trend. Animator Kazuya Kanehisa handled it in his retro style — he’s also known for his amazing (and fake) mid-century iPhone commercial.

You may be familiar with The Little Mole, the Czech cartoon. Its creator, Zdeněk Miler, also did a charming series called The Cricket (1978–1979), which now has an official YouTube upload. Check out this episode as a start.

See you again soon!

Otsuka wrote about his experiences at the Funabashi races in The Aspirations of Little Nemo (リトル・ニモの野望), whose section on Lupin is one of our main sources today.

From the documentary Yasuo Otsuka’s Joy of Motion.

From the Lupin section of the book Yasuo Otsuka Interview (大塚康生インタビュー), the most important source for the issue, cited throughout.

Miyazaki shared a tale of Otsuka’s drunk driving in Starting Point 1979–1996 (“A ‘Slanderous’ Portrait”). We also reference “Hayao Miyazaki on His Own Works,” “Lupin Was Truly a Creature of His Era” and “A Woman Finish Inspector” from the same book.

Otsuka mentioned the realistic depiction of vehicles as part of the Lupin proposal in Drawings Covered in Sweat: Latest Revised Edition, another important source.

Osumi spoke about the “live-action feel” of Lupin in Animage (February 1986). The point about Eisenstein comes from his interview in the book The Gods of the Anime Powerhouse (アニメ大国の神様たち), a key source. He also told the Asahi Shimbun about Lupin’s filmmaking tricks in a 2001 interview that we’ve quoted multiple times.

The word “anime” wasn’t standard yet. In those days, TV animation was often called “TV manga” — cartoons.

Osumi’s disappearance is discussed in The Gods of the Anime Powerhouse and a 2008 TV interview, transcribed here.

Takahata’s quotes here come from an essay in his book Thoughts While Making Movies (“いろんなルパンがありまして”), used a few times.

Episode five was credited to Osumi, but Otsuka recalled in Yasuo Otsuka Interview that Takahata and Miyazaki were involved in it — although not in episode six.

The point about shortening Fujiko’s hair comes from Lupin the Third Part 1 Storyboards: A Collection of Treasured Materials. Miyazaki’s quote about her character appears in a roundtable interview from Animage (October 1984). It’s worth noting that, as seen in his 1980 episode Wings of Death: Albatross, Miyazaki wasn’t strictly opposed to the sex comedy aspect of Lupin — so long as it was handled a certain way.

From Saida’s interview in Future Boy Conan: Film 1/24 Special Issue (1979). We also cite the ones with Miyazaki (for the detail about working New Year’s) and Koichi Murata.

These points, and many more about the individual episodes, get hit in Yasuo Otsuka Interview.

From Takahata’s interview in The Phantom Pippi Longstocking.

I was madly in love with Lupin, Fujiko cursed my soul (80% of my fetish side thanks to her, 10% "The Chauffeur" Duran Duran, ! 10% various and possible stuff), and the soundtrack is a masterpiece, (I got it!) one of the best ever! BUT, dear Hayao, in your wonderful career, you made a terrible mistake: In the iconic image (which I can't add!) where Jigen is trying to fix something in the engine with Lupin resting on top, you showed him working in front of the car, but the engine for the mighty Fiat 500 is in the back! Ah ah!:)) I have forgiven you...

I enjoyed reading this piece! Your detailed exploration of Lupin the 3rd's origins was fascinating, especially the insights into Yasuo Otsuka's passion for accurately depicting cars and objects. Additionally, how you captured the transition under Miyazaki and Takahata added a dynamic and engaging layer to the story.