Welcome! We’re here with a new edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. This is our lineup today:

1) Inside Lucky Dog, a new musical from India.

2) Animation news.

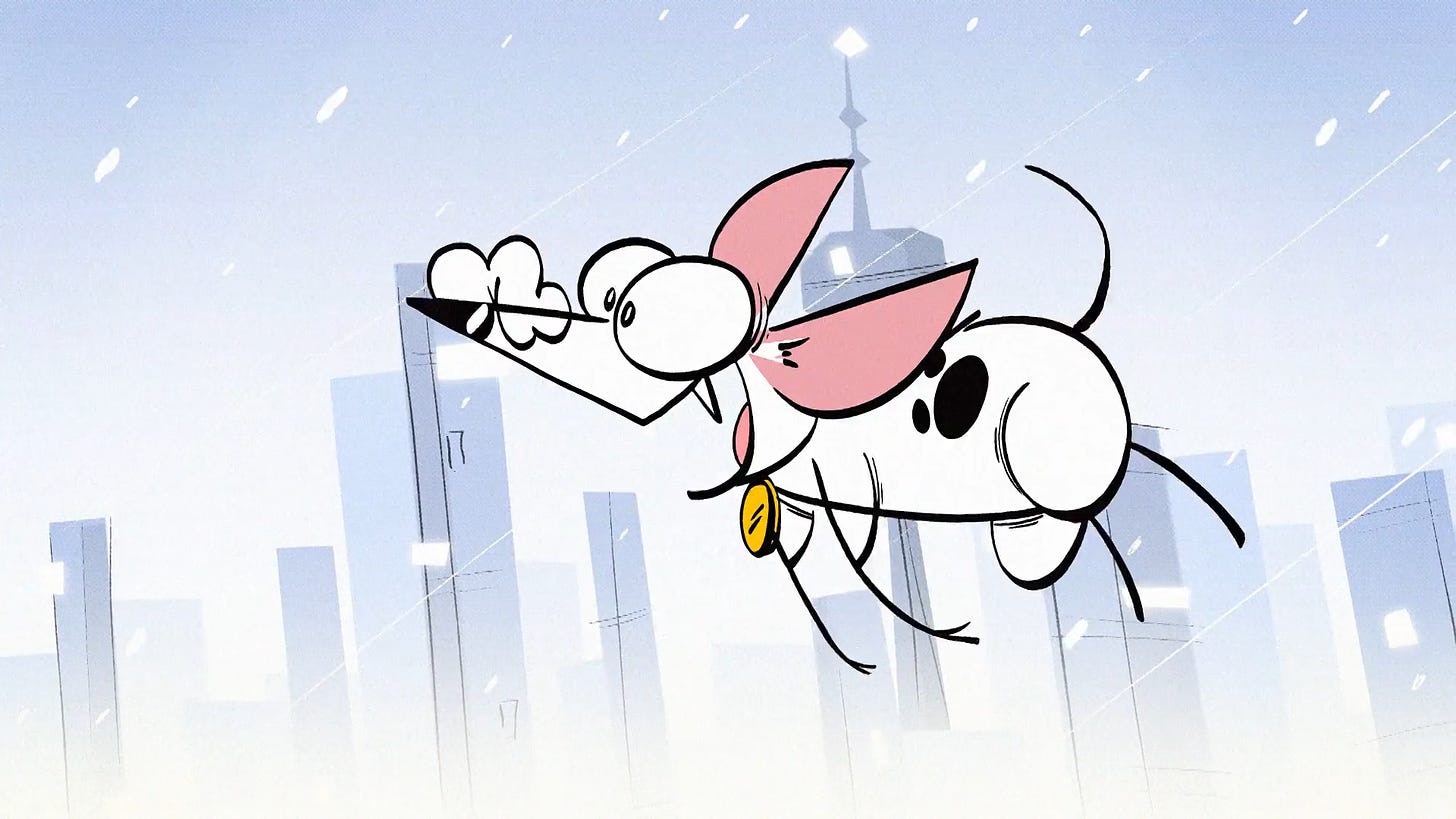

A tidbit before we begin — Snif & Snüf is taking off on YouTube, with close to 100,000 views already. We linked it last week, but, if you’ve missed it so far, we definitely recommend it. (The film’s creator spoke about it with Cartoon Brew this week.)

With that, here we go!

1 – An independent gamble

Animation from India is rising. Not everyone knows it yet, but it’s true. Today, the work of India’s independent animators can be many things: fun and whimsical (Seen It!), surreal and gruesome (Wade), charming and hilarious (anything Lamput). Teams like Studio Eeksaurus and Vaibhav Studios put incredible life into their projects.

Add to that group Ujwal Nair, an animator based in Chennai. Recently, he’s premiered his latest film — finished this past December after years in the making. It’s called Lucky Dog, and it’s an animated musical for adults.

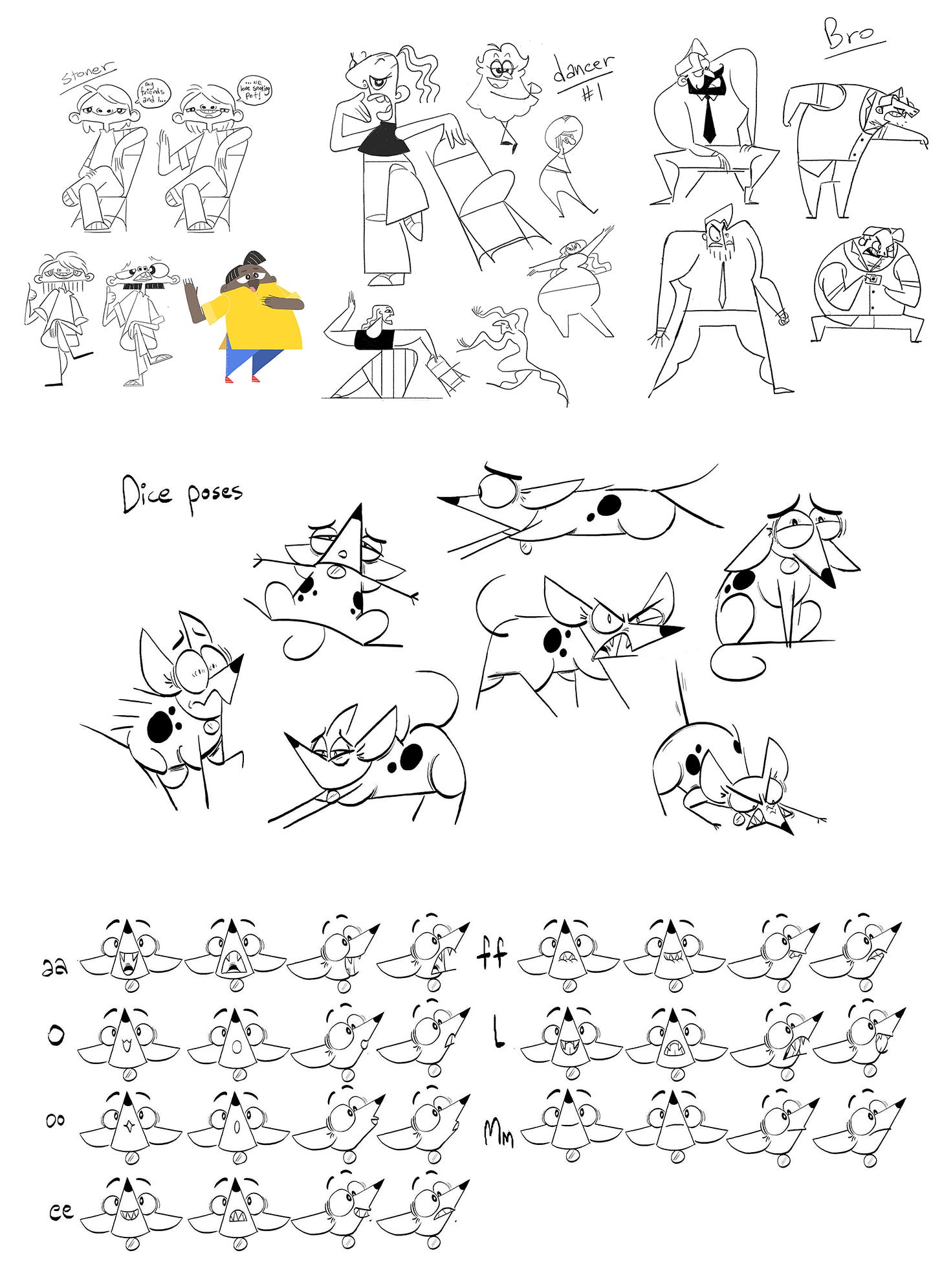

Nair has drawn notice with his animation (like the enjoyable KPL) before. But he’s hit a new artistic high with Lucky Dog. This one is about a dog named Dice whose owner, Disha, moves away to Canada. The question: can Dice get his own visa and join her? What comes next is a funny satire that has lots to say — and offers lots to see and hear.

Lucky Dog pairs crisp, inventive cartooning in the UPA vein with a soundtrack that took us by surprise. There’s great singing here, with lyrics that stay smart throughout. The story tackles everything from the idealization of North America (“We remain enamored with the West / A place where everything is great and no one is depressed”) to the bigotry that immigrants can face when they come to India itself.

Waiting at the Canadian embassy, Dice watches as a singer and dancer gets denied a visa to “the second-best country in the universe.” (Like the chorus explains, “We are all finally okay / With the idea that we’ll never live in USA.”) Soon, Dice gets into his own life story, from surviving as a puppy on the streets to thriving as Disha’s pet in a middle-class apartment, where he doesn’t get along with the local bugs.

The film earns big laughs, but it’s not all jokes — Lucky Dog has emotional range. It’s over 20 minutes long, and it takes you on a journey. We came away impressed when we watched it earlier this month. And so we decided to interview its director.

Below, Nair offers a window into the process of Lucky Dog, and into the realities of making independent animation in India. We’re happy to share his insights today — plus concept materials and a short excerpt from the film. Our discussion, edited for formatting and flow, follows.

Animation Obsessive: What was the inspiration behind Lucky Dog? Musicals are a tricky thing to get right — what made you decide to tackle one here?

Ujwal Nair: The inspiration for Lucky Dog came from a personal experience. I was born and raised in India and, like many Indians of my generation, I dreamt of immigrating to the West.

In 2016, I decided to move to Canada. But, to my dismay, I was denied a visa.

Around the same time, a friend of mine moved to Canada with five of her cats. I thought it was really amusing (and kind of unfair) that those cats had succeeded where I had failed. I thought, “Why do they get to live in Canada? They don’t even know what Canada is!”

But then I thought, “What if they did? What if Indians are so obsessed with going abroad that it’s rubbing off on their pets?” That’s how I came up with the idea of a pet that wants to immigrate to a foreign country. It seemed like it had potential as a satire about immigration.

The story is told almost entirely from the perspective of Dice, the dog protagonist, and it felt like playful lyrics would be a more engaging way to listen to his story than a traditional voice-over. Also, the film is quite emotional, and music has the ability not only to capture but to elevate the emotions of a story.

But I had no idea how hard (and expensive) it would be to make a musical! I’d never done it before and I explored the medium this time because it seemed like a good fit for this project.

As an independent animator, what was your process behind such a long and ambitious film? Especially since you seem to have done so much of Lucky Dog alone.

The project took four years to complete due to its length and limited budget. The bulk of the budget was allocated to music and sound, which left me with very little money for visual development and animation.

As a result, I had to take on a majority of the visual art roles. On top of that, I had a day job, so it wasn’t possible to do multiple things for the film in tandem. I decided to go about it one step at a time.

My co-producer Indou Theagrajan and I followed the well-established animation pipeline because we wanted pre-production to be rock solid. The script and lyrics I wrote back in 2020 remained unchanged throughout production. We hired composer Aditi Ramesh in 2021, and I began working on the animatic after approving and signing off on her scratch tracks.

I did all the rough animation and layouts in the animatic. That way, the cleanup animators could focus on keeping the characters on-model, without worrying about timing and spacing. It was like a relay race in which we had to ensure the baton was passed securely from one stage to the next.

How many people in total were on the team, where were you all based and where did the funding come from to make a four-year film?

Lucky Dog was entirely self-financed. We applied for a few art grants, as we didn’t come across many grants for films or animated projects in India. However, that didn’t work out. At some point, I realized that, if I wanted to get the film made, I’d need to finance it myself.

I was getting a steady income from my day job and I had some money saved up. I decided to spend most of it on this film. It was a hard decision, but I’m grateful that it enabled me to hire and work with talented artists!

Eighteen people worked on the film. The music team comprised eight artists, including our composer Aditi Ramesh. The sound and Foley team consisted of five artists, led by our sound designer Dinesh Kumar. And the animation team consisted of three cleanup and in-between animators — Subhajit Kar, Suman Manna and me — and one animation colorist, Labani Ganguly.

We were based in different cities across India — Indou and I are from Chennai, and the other artists are from Bengaluru, Kolkata and Mumbai.

What were some of your biggest concerns and focuses while developing and recording the songs?

My biggest were rhythm, tempo and acting. Rhythm and tempo were going to affect the pacing and comedic timing of the film, and voice acting was going to influence the body language and expressions of the characters. That’s why I wanted the songs to be in place before I storyboarded the film.

Along with the script and lyrics, I gave Aditi detailed briefs for every song. These included how long each song needed to be, their tonal shifts, the changes in pace and the emotional states of the characters.

I mentioned where I wanted musical interludes with no vocals, where I wanted silence and where I wanted lines to be spoken rather than sung. I also gave her references from stage musicals and musical comedy acts. Aditi stuck to the briefs and worked with the singers and musicians to compose seven unique songs for the film, each with great melodies, instrumentation and harmonies.

Do you remember the first moment when it felt like the film was working?

To be honest, once I finished writing the script, I was fairly confident that it would work as a film. I grew up appreciating screenwriters and their contribution to the quality of films. After spending a year on the story, lyrics and screenplay, I was happy with the structure, pacing and tone of the script. I thought I had a good foundation on which to build the rest.

The film has a super slick, thoroughly designed art and animation style. How did you arrive at it?

Thank you for saying that! The goal was to simplify the visual elements and animation style to be production-friendly. I needed all the characters’ movements and expressions to be readable. There’s a lot of story and gags packed into the 21-minute runtime, and I didn’t want anything to be incoherent or confusing.

The characters have clearly defined shapes and outlines, and I animated them on “threes” and “twos” so that I didn’t have to clean up several key frames every second. Strong key poses and an adequate number of in-betweens, with emphasis on ease-in and ease-out drawings, were crucial in making the movements register without looking stilted.

While my goal was to keep things simple, I didn’t want to compromise on playfulness. Dice resembles a playing die, so I designed the floor like a Snakes and Ladders or Ludo board that he could roll on. That’s where the flat-perspective compositions came from. It worked because it gave the world a sense of order that I think Dice would appreciate!

The creatures [in the apartment] were meant to spook Dice, so they have stick-figure limbs and big eyes that make them look creepy and skeletal. I gave the humans similar features to create consistency in the character designs.

What musical and visual influences did you draw on for Lucky Dog?

While writing the script, I was really inspired by stage musicals like The Book of Mormon and Hamilton, and musical comedy acts by Tim Minchin and Bo Burnham. Those were some of the references I shared with Aditi as well.

When it came to the visual aspects, I was influenced by the work of Brad Bird, Genndy Tartakovsky, Cartoon Saloon and Sylvain Chomet. I love the character performances and set pieces in Brad Bird’s films and I’ve always admired the shape language in Genndy Tartakovsky’s and Cartoon Saloon’s work. I also love the linework and use of colors in Sylvain Chomet’s films. It gives them a funny and melancholic tone that I wanted to bring to Lucky Dog.

Did you have any kind of animation community near you during the production — people to bounce ideas off of or show your progress to?

Yes, I did! The first person I share my ideas with is Indou, my wife and co-producer. She doesn’t have a background in animation or film, but she is artistically inclined and has good taste. She’s also quite opinionated — she can decide if she likes something or not very quickly, which helps me understand if something I’ve done is working.

In addition to Indou, I brought an Indian animation filmmaker named Krishna Chandran on board as a creative consultant to help guide us through the visual development and production process. He gave us good practical advice on designing the characters and simplifying our pipeline.

And I had other animator and writer friends who questioned some of the choices I made at the story outline stage. During visual development, when I was experimenting with bright colors, some of them thought it was too saturated and harsh. Their feedback helped me iron out some of the issues with the plot and character development and tone down some of my aesthetic choices.

I’m very grateful to be surrounded by talented artists who have my back.

What was it like seeing the final cut for the first time?

I was genuinely pleased with it. It was such a relief!

Toward the end of the project, I was caught up in minute details like the consistency of the line quality, the treatment and colors of background elements and the texture of the sound design. I wasn’t sure how well everything would mesh. But, once I saw all the pieces come together, I was giddy with delight! It was quite satisfying.

There’s amazing creativity in Indian animation — Lucky Dog is part of this, alongside the work of groups like Eeksaurus, Vaibhav and more. Where do you see things headed for animators in India?

I’m honored to be mentioned in the same breath as them. I grew up watching their work and continue to be in awe of them. Vaibhav and Eeksaurus have invested a lot of time and money in their independent animated films, and what I love about their commercials is that they are imbued with an independent spirit. They’re always pushing the boundaries of the medium.

I honestly believe the future is bright for independent animators in India. We have access to great, easy-to-use software, and we can watch films and cartoons from pretty much any part of the world. I’ve learned so much just from watching animated clips frame by frame on YouTube (using the angle brackets, for those who don’t know!). It’s a tremendous resource.

The only thing holding us back is that we haven’t cracked distribution yet. There’s clearly a lot of talent here, but we need to find ways to gain visibility.

Lastly, what do you hope people take away from Lucky Dog?

When I was denied a visa, it came as a surprise because I didn’t know anyone else who’d had that experience. It’s possible that it hadn’t happened to anyone I knew personally, but, if it had, it’s very likely they’d kept it to themselves. Understandably, there’s a lot of embarrassment associated with rejection and failure.

I hope the film gets people to think about moments of rejection in their lives, contextualize them and gain the courage to talk about them, because it does help others who go through similar experiences.

I also hope the film is a testament to the growth of independent animation in India. Despite the lack of funding, there are artists out here who are dedicated to honing their craft, and willing to take a chance on ambitious projects they believe in. Here’s hoping the gamble pays off!

Our thanks to Nair for taking time out to talk to us. After the interview, he mentioned that Lucky Dog is being submitted to film festivals right now: “We have done a couple of special screenings in India so far and we’re hoping to travel to other parts of the world with the film this year.” We wish him and the team the best as the rollout of Lucky Dog continues.

2 – Newsbits

We lost animator and designer Mutsumi Inomata (63), an anime industry veteran — and the artist behind the characters of many Tales of games.

Boonie Bears: Time Twist is the second-biggest animated film ever in China, beating the record set by Chang’an last year. It’s earned more than 1.969 billion yuan (over $275 million) to date, according to Maoyan.

In Japan, director Sunao Katabuchi discussed the progress of his next feature, The Mourning Children. Its beautiful pilot last September was among our very favorite pieces of 2023.

An animated project called Mmanwu is being crowdfunded right now. Made in America, it’s a horror film set in Nigeria, and the team has already completed and shared its pilot trailer.

Canada’s Preston Mutanga, the teenage animator behind the Lego sequence in Across the Spider-Verse, spoke to BlkWmnAnimator about working on that film and more.

In Kazakhstan, Tasqyn Studio released another episode of its YouTube children’s series Puppies (Kunshikter). The team, which won an award in France for its short Partner last year, reportedly had 75 members as of April 2023.

The Canadian film Dounia: The Great White North got an award at NYICFF this week, and opened in Spain. It’s about a Syrian girl finding a new home in Canada. Director Marya Zarif was likewise born in Syria and lives today in Montreal.

Also at NYICFF, Daisuke Nishio of Japan won a prize for his 3D film Magic Candies. He’s known for anime series like Pretty Cure and Dragon Ball Z, but this short (produced by Toei) takes him in a different direction. There was a Q&A session after its premiere at the festival.

Speaking of Q&A sessions, Austrian animator Bahi JD held one on Twitter, revealing a few secrets of his craft. “Show your animation to your grandpa, and ask, ‘Did you get it?’ ” he wrote. “I’m not joking. If your grandpa doesn’t get it, no one can.”

Lastly, we wrote about the ups and downs of cel animation.

See you again soon!

Re Lucky Dog - having followed the course of animation in India since the early 80’s I’ve always felt that the future lies in the hands of independents, and it’s been a long journey.

A bit like imagining what American animation would be like if Disney’s “Snow White” had not been the huge success that it was.

The early ‘00’s were marked by a few prestigious, well-financed features launched to great fanfare but that uniformly tanked despite the involvement of many talents - a case of running before you can walk.

Sitting here in London and taking a somewhat cynical view of what was playing out , a view shared by Ram Mohan, the director of the “Ramayana”, I think I may have annoyed a few of the main players but frankly, no one was going to listen to what I had to say..:)

I do remember a very respected animation scholar telling me that she “didn’t expect much” when it came to animation from India so I guess it’s just been a matter of time for things to gain traction as people work in private on their films.

The big, blousy, high profile projects have mostly failed and carry a great deal of financial risk that demand international distribution, but that hasn’t been forthcoming in the past and the subjects have been too localised - the “Ramayana” being a case in point.

Another aspect has been access & I think YouTube has been the big game changer as far as getting those independent shorts out there and finding an audience eg in the case of Eekasaurus’ films - films are no longer subject to the whims of possessive distributors.