Welcome back to the Animation Obsessive newsletter! We’re glad you could join us. This week, we’ve got an exciting lineup in store:

One — what separates Ghibli stories from the Hollywood template?

Two — the week’s animation news from around the world.

Three — the retro ad of the week.

Four — the last word.

Before we get started — are you new to our newsletter? Signing up is fast and free. Catch new issues in your inbox every Sunday:

With that out of the way, let’s go!

1. Ghibli’s un-Hollywood stories

Decades ago, when Japanese animation first started hitting the mainstream in America, audiences could already tell that Studio Ghibli stood out. There was something so unique, so different, about the way it made movies.

It goes deeper than a vibe or a visual look. It’s in the storytelling. My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service and Grave of the Fireflies were stories radically at odds with the Hollywood norm at that time. They’ve grown influential in the years since — but exactly what makes them work has proven slippery.

It’s clear that the talent at Ghibli is behind a lot of it. From Hayao Miyazaki to Isao Takahata and beyond, the studio’s been a hub for some of the best filmmakers in the world. You can’t boil them down to a formula.

That said, there are concrete differences between Ghibli stories and the standard American film script worth dissecting. And the first is something that Ghibli stories share with most anime — a plot structure called kishōtenketsu.

A different kind of storytelling

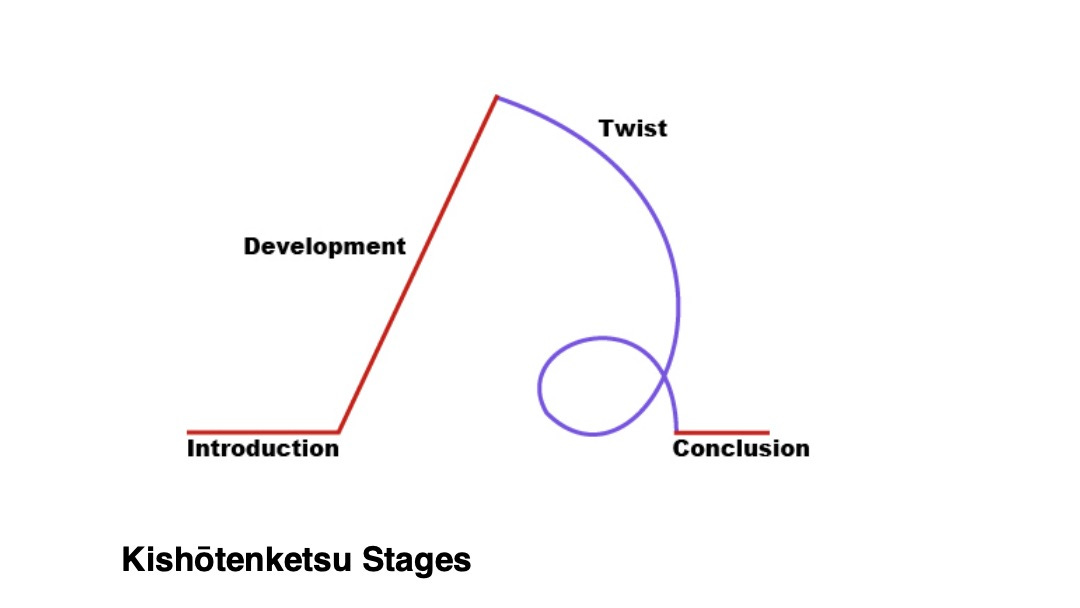

Kishōtenketsu is a method of storytelling that dates to ancient times in Japan. You’ll find it in Chinese and Korean writing, too, under different names. The structure is composed of four parts — ki (introduction), shō (development), ten (turn or twist) and ketsu (conclusion).

As the writer Jianan Qian beautifully explained in The Millions, kishōtenketsu doesn’t work like stories from elsewhere in the world. It has a “wandering quality,” which can feel unusual to people who don’t know East Asian storytelling. The structure can lend itself to long, quiet passages — only for a twist to shake things up. It concludes by reconciling the twist with the rest of the story, revealing the connections between them.

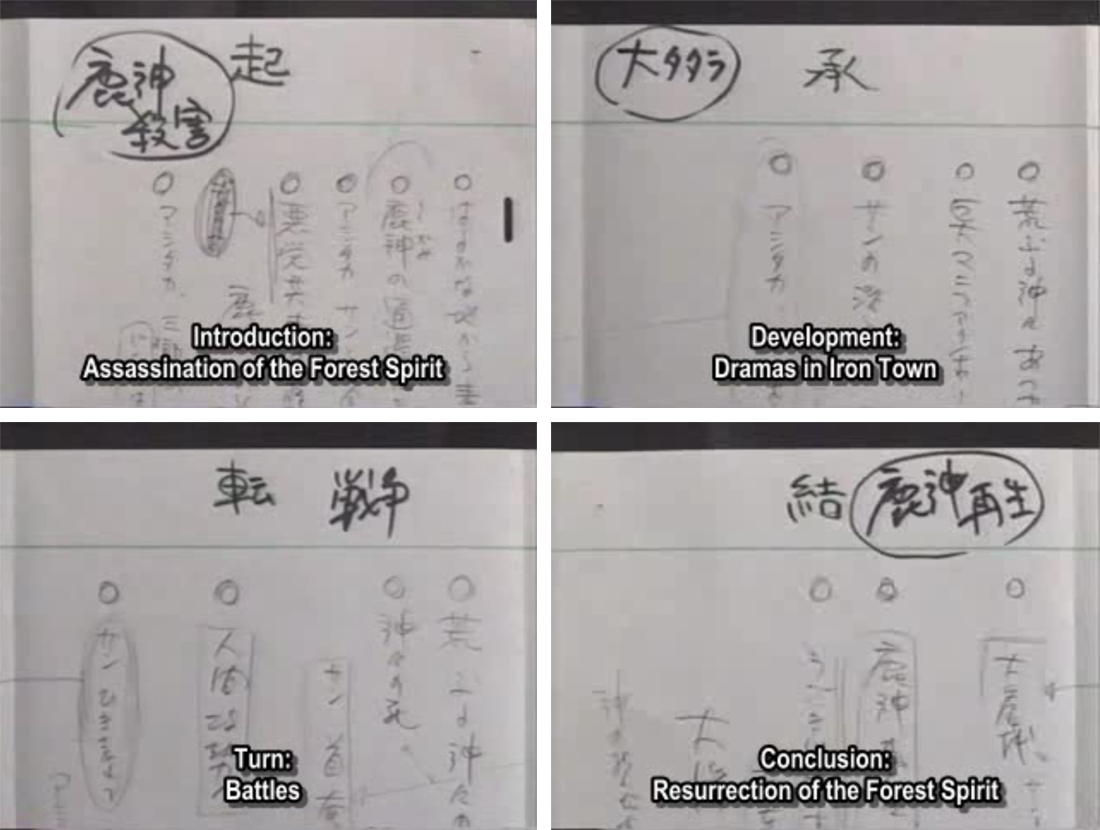

This way of telling a story is incredibly common in Japanese anime and manga — including Ghibli’s. Even before his time at the studio, Miyazaki was already using kishōtenketsu to plan the story for The Castle of Cagliostro. As he once explained:

According to kishōtenketsu, I divided the work into four parts — A, B, C and D — and as we proceeded in our tasks to part C, it became clear that we were considerably over the foot length and that we would end up way over the set film length.1

Although Cagliostro bears some resemblance to Hollywood storytelling, kishōtenketsu can drift into very un-Hollywood territory. The average screenwriter in America uses the three-act structure — the inciting incident, rising action and climax we all recognize. That structure is powered by a driving conflict, but kishōtenketsu’s approach is a bit different.

With kishōtenketsu, stories don’t ultimately center on conflict. Many feature conflict, but the bones of the structure are development and change. If you lean hard on this subtle distinction, the gap between stories made with kishōtenketsu and those made with the three-act structure grows vast. At times, Ghibli has done just that.

My Neighbor Totoro is the clearest example. It lacks a driving conflict — which has led some American critics over the years to say that “nothing happens” in it. But that’s not quite right. Under the hood, the kishōtenketsu structure is at work. It introduces and develops the setting, as Satsuki and Mei arrive in rural Japan and meet Totoro. When Mei runs off, it’s a sudden twist that comes out of the blue. Then, order is restored.

None of this is to say that Ghibli films contain no strife — most are packed with it. Miyazaki himself has said that he’s “one of those who feel that a film should show some problem being overcome, even if it’s a small one.” But the nature of kishōtenketsu is such that even Ghibli films about war and death, like Grave of the Fireflies, don’t explore those issues quite like standard Hollywood stories.

It’s similar to the concept of ma, which Miyazaki famously discussed with Roger Ebert in 2002. After clapping his hands, Miyazaki said, “The time in between my clapping is ma. If you just have non-stop action with no breathing space at all, it’s just busyness.” That sense of space is baked into the core of kishōtenketsu, and it can bubble up in small and surprising ways throughout an entire film.

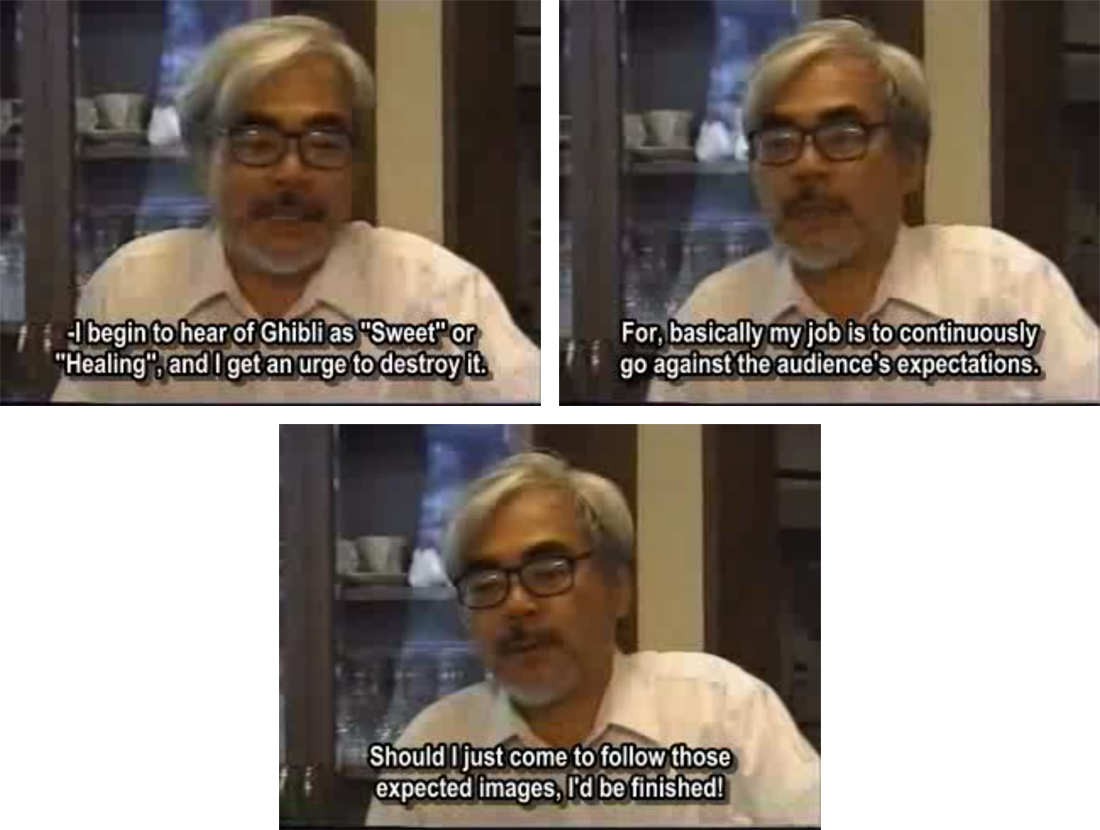

Still, there’s something that looms larger than kishōtenketsu over Ghibli’s storytelling — at least in Miyazaki’s case. And that’s his rebellious, intuitive process. It’s defined Miyazaki since the beginning. In his later years, it’s led him to break away from kishōtenketsu itself.

A different different kind of storytelling

The way Miyazaki makes films is both widely documented and little known. At its core, it’s about process rather than planning. Miyazaki’s goal is to bring into the world beautiful films that he says already exist. He can’t see them fully, and even he doesn’t know how they’ll end. So, he leads the group struggle to find the film, starting with his own snatches and snippets of ideas.

Takahata, his late mentor, explained the process in the 2000s:

Hayao Miyazaki stopped writing screenplays a long time ago. He doesn’t even bother to first finalize the storyboards. … After diving into the process, he then begins to create storyboards while doing all his other work, from key animation on down. Using his powers of continuous concentration, the production starts to take on the elements of an endlessly improvised performance.

It started as Miyazaki’s way of navigating Japan’s brutal animation industry, where those in charge never gave him time to write or storyboard. Cagliostro was in production for around five months, and he was storyboarding all the way. He wrote a screenplay for it, too, but it met the realities of production.

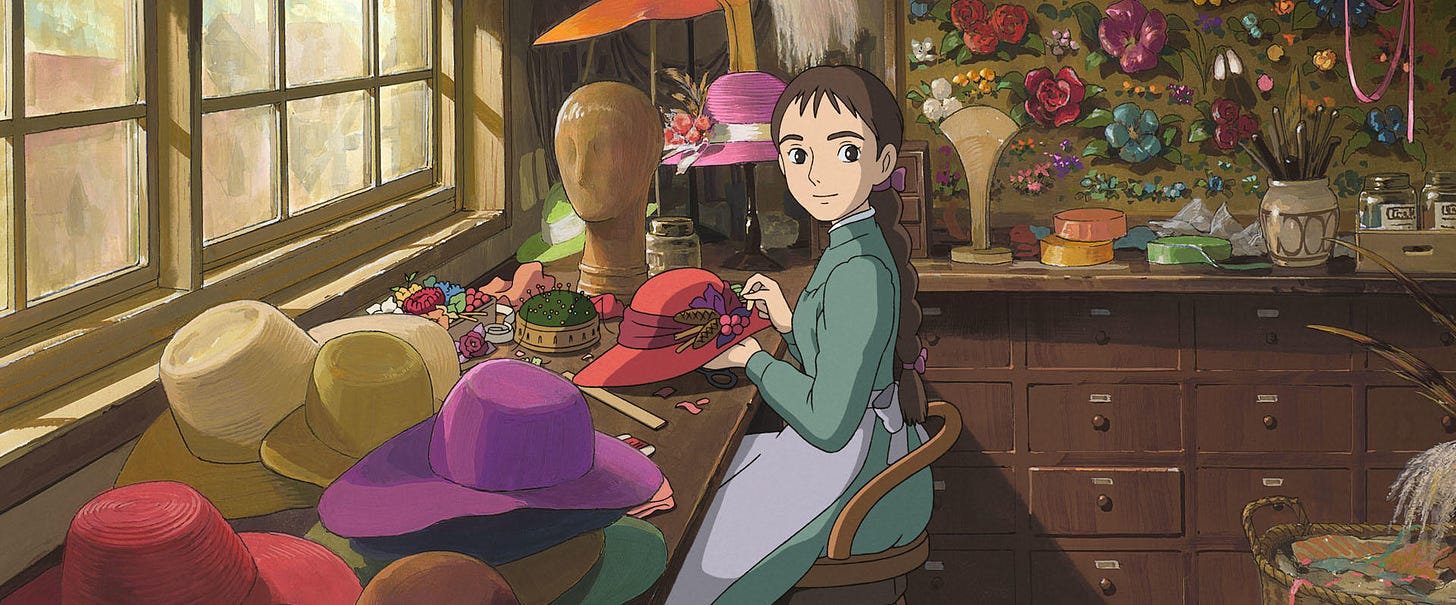

As the years passed, it all developed into an ethos. Miyazaki’s quest for the freshness, originality and beauty you see in his films drove him further into his process. His own fiery rebelliousness and strong views only fueled it, and kishōtenketsu increasingly strained to contain him. By the time of Howl’s Moving Castle, Miyazaki had abandoned traditional plot structure. Instead, he allowed the process to structure the story.

This went beyond un-Hollywood — it was a huge point of contention in Japan. Howl polarized Japanese audiences, many of whom expect kishōtenketsu like many American moviegoers expect the three-act structure. “Some said they liked it from the bottom of their hearts,” Miyazaki later said, “while others said they didn't understand it at all.”

On the Japanese-language internet, it’s common to see a Miyazaki quote from the making of Ponyo, where he dismisses the idea of delivering a tidy kishōtenketsu structure. The one-of-a-kind, homebrew stories of Miyazaki’s latter-day films bear the traces of kishōtenketsu — but they’ve morphed into something else entirely.

Miyazaki was outraged, he said, by the initial reaction to Howl. Many in Japan still haven’t come around to it. In fact, this has been the case with most of Miyazaki’s work since Spirited Away, the peak of Ghibli’s success in Japan. As Miyazaki drifts deeper into his own form of storytelling, his stories feel wildly unfamiliar even at home.

With Ghibli, though, giving the audience what it thinks it wants has rarely been the point. Even all these years later, there’s still something so unique, so different, about the way it makes movies.

2. Headlines around the world

Daytime Emmy nominees revealed

On Tuesday, the Daytime Emmy Awards announced the 2021 nominees for animation. Like last year, Disney Junior’s Elena of Avalor came out ahead with eight nominations. But not everything is the same. As Cartoon Brew reports, streaming services beat TV this year — thanks to the combined pull of Netflix, Disney+, Hulu, HBO Max, Apple TV+, Peacock and Amazon Prime Video. That’s a long list, and it’s only growing.

With 20 nominations, Netflix leads among streaming platforms. Its Hilda has the most for a streaming series (five), tied with Hulu’s Animaniacs. Netflix is also the only streamer to compete in the Outstanding Children’s Animated Series category, where it holds three of the five slots.

Across all categories, Hulu, HBO Max and Apple TV+ tie with eight, while Disney+ follows with seven. Disney+ may be behind, but Disney leads animation overall with 28 nominations between its streaming and TV branches. Its top streaming nominee this year is Star Wars: The Clone Wars, with three.

You’ll find the full list of Daytime Emmy nominees over on Animation World Network.

BUSINESS: The labor crisis in Japanese animation

Driven by the streaming boom, demand for Japanese anime has exploded worldwide. Netflix and other foreign-born services are commissioning countless original series. It’s a mad rush for new content — and the results are mismanagement and miserable working conditions. At studios like MAPPA, the wick is burning at both ends. Their output is high, but fewer and fewer Japanese animators want to work for them.

“Perhaps the biggest problem in the Japanese animation industry,” one director said back in 2019, “is that there are no more young animators.”

This week, several stories illustrated the crisis. One was sparked by a tweet from veteran animator Ippei Ichii, which Anime News Network translated as follows:

Apparently, a producer working on a Netflix anime made at MAPPA suggested to pay 3,800 yen (US$34) per cut. The budget for TV series is between 3,800 to 7,000 yen, so if you accept that offer, the unit price for animators would go down. Heads-up: If you're asked, I think it’s best to negotiate for 15,000 yen (US$134) or more.

A cut is an unbroken shot of any length, with key animation by a single artist. Cuts go for 4,500 yen on average, per another animator in the discussion. That’s a dismal sum, but Netflix is trying to push it lower, Ichii wrote. “For all the exorbitant amount of capital they have,” he remarked, “it’s a problem that they’ve started to place orders with such low rates.”

But studios still need to fill those orders, even if Japanese animators won’t. And so they’re turning to enthusiastic foreign freelancers — many of whom don’t speak Japanese. ANN published another eye-widening piece this week that explained, “In today’s understaffed industry, it’s possible for practically anyone with an online presence and art samples to receive an invitation to work on a Japanese anime.”

Chaos has ensued. ANN’s article highlights two of the freelance assistants who translate between producers and their overseas teams. This crucial job, one of them says, is sometimes given to “the first person who knows passable English.” Vetting for foreign artists is similar — some of the hires have little training in art at all. And the work remains thankless, with limited pay, spotty credit and poor management.

One last aspect of Japan’s labor crisis was laid out this week by the site MagMix. In Japan, animation studios nearly all work for hire. The “production committee” system insulates studios and their outside investors from risk — but it also funnels the vast majority of the profits into investors’ hands. A big show doesn’t equal a big payout for its animators. MagMix notes that MAPPA is moving to change this, but time will tell.

Best of the rest

Cartoon Network Africa revealed a new, locally made series — My Cartoon Friend by Lwazi Msipha (South Africa).

News of a Final Fantasy IX animated series broke last week, and now another Japanese PSX game is getting one — Legend of Mana.

Speaking of Japan’s production committee system, TMS is also aiming for reform via its “Unlimited Produce” project, according to a press release this week. It’s led to the new Resident Evil series, due July 8 on Netflix.

One final news item from Japan — Mobile Suit Gundam Hathaway is the series’ biggest success in domestic theaters since 1988. Catch it on Netflix in the U.S.

We learned this week that NewQuest Capital bought the Indian animation studio Cosmos-Maya. What does that mean? Major expansion in India, Canada and America — through the purchase of existing companies. This may be a trend.

Meanwhile, the Indian animator Divakar Kuppan unveiled his next film, Tobacco and the Flower. AnimationXpress has the story.

A bizarre new chapter in the animation gold rush. In America, Great Wolf Resorts is getting into cartoons. The talented Six Point Harness (Hair Love, Guava Island) is attached.

Conceived in 2006, the Ukrainian feature Viktor_Robot finally saw wide release on June 24. We missed this one last week. The trailer is worth your time.

Another we missed. In Russia, the Ministry of Culture says that backing Soyuzmultfilm has paid off, per TASS. The studio accounted for 10% of cartoons on Russian TV last year, and 400 hours’ worth of its animation has aired in 2021.

3. Retro ad of the week

This week, we’re putting a spotlight on the weirdest ad we’ve ever featured. It’s a late commercial from the filmmaking duo Faith and John Hubley, likely dating to the early 1970s. The weirdness comes not from the ad itself, but from the product it advertises. That product is Flavor Maker — a bottled condiment for dog food.

Flavor Maker’s existence raises important questions. We found most of the answers in this syndicated newspaper article from late 1972:

Just as humans have refined their tastes in terms of beauty and a sophisticated palate, it is the belief of DeWitt Helm Jr., president of Miller-Morton (makers of Sergeant’s), that precisely the same trend now exists for the 32 million dogs and 22 million cats residing in American homes.

“It’s truly the age of affluence,” Helm pointed out, “when one of the key items to emerge is a dog food flavoring developed to pique the palate of the fussiest canine.”

Formulated to enhance dry, moist or semimoist food and even, heaven forbid, table scraps, there is an enticing sauce, complete with a rich, meaty flavor and a scent to wow the woof and turn the most ordinary meal into haute cuisine. It could easily become the mustard or barbecue sauce of dogdom.

It’s funny, but also kind of dystopian. Flavor Maker’s trademark was registered in late ‘68, after a year of assassinations, mass protests and war. In 1972, the article above ran beside a much smaller newsbit in The Danville Register — word that Charles Colson, Nixon’s hatchet man, would leave government in the wake of the Watergate burglary. In context, the “barbecue sauce of dogdom” was breathtakingly decadent.

Somehow, though, the Hubleys turn a dystopian product into a solid ad. Their spot stars a mother dog who uses Flavor Maker to get her picky son to eat — all rendered in the organic style that was the Hubleys’ signature by this time. The animator is unclear, but it may be Tissa David, their frequent collaborator. Flavor Maker itself has been off the shelves since at least 1990, but the Hubleys’ ad still intrigues:

4. Last word

That’s it for this week! We hope you’ve enjoyed.

One last thing. It’s July 4, and that means We the People is out on Netflix. We’ve decided to end by linking to two interviews tied to the anthology. The first, from Animation Magazine, is a chat with Tim Rauch, Peter Ramsey and showrunner Chris Nee. The second is another with Ramsey on Animation Scoop. Both are informative, and not only about We the People. If you want more to read, they’re worth a look.

Hope to see you again soon!

From Starting Point: 1979–1996, which we quote throughout the article. This one passage is slightly edited from the translation by Beth Cary and Frederik L. Schodt. Their version confusingly renders kishōtenketsu as “plot turns and conclusion,” which obscures Miyazaki’s meaning in the original Japanese.

The whole section on storytelling had my heart racing.

Hi, this is a super lovely and informative article! I was hoping to ask for a source for the Takahata quote? I haven’t been able to find where it’s from, and it seems like a super interesting interview! Thanks:)