Welcome! We’re here with another Sunday edition of the Animation Obsessive newsletter. This is the agenda today:

1) The story of Mt. Head (2002) by Koji Yamamura.

2) Akira Toriyama’s passing and other animation news.

For those new to what we do here — it’s free to sign up for our Sunday issues. Get them in your inbox weekly:

With that, here we go!

1 – The rise of Mt. Head

Tonight, with The Boy and the Heron, Hayao Miyazaki won his second Oscar. In the process, he ended an almost two-decade streak of American victories in the Best Animated Feature category. It’s a huge honor for a stunning film — by far his biggest in US theaters.

But this didn’t happen randomly. The Boy and the Heron’s win has a foundation under it: Miyazaki is a living legend, and Japan’s animators are the most admired (and most influential) anywhere. That’s been true for a long time. In fact, it was a little over 20 years ago when Japanese animation first broke through at the Oscars.

In 2003, Spirited Away won — something we’ve written a little about before. That award signaled the full acceptance of Miyazaki, and by extension anime itself, into the Hollywood mainstream. If you were to pinpoint the moment when Japanese animation officially took over, you could do worse than the 2003 Oscars.

It wasn’t only Miyazaki’s win that made the 2003 ceremony so important for Japanese animators. Lower down the ballot, something else happened, too. An animator from Japan was nominated for Best Animated Short — for the first time in the category’s 70-year history.1

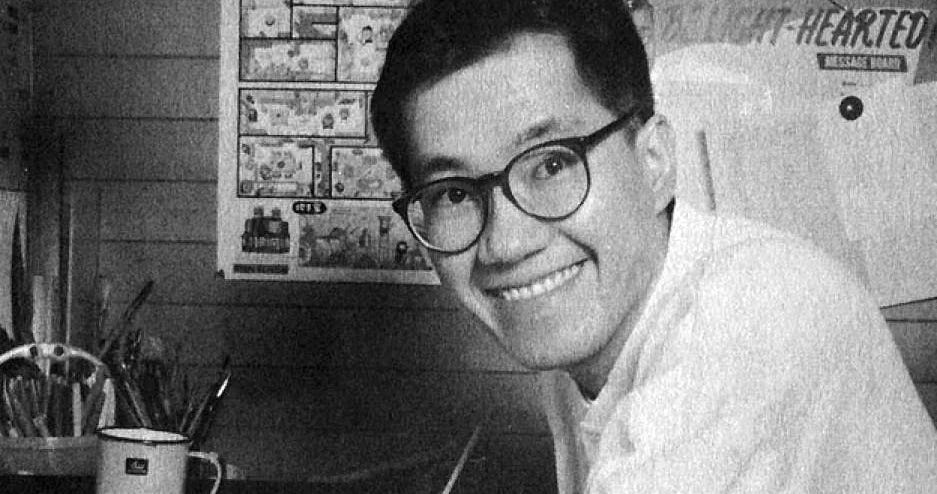

That animator was Koji Yamamura, with Mt. Head.

Like the award for Spirited Away, the Mt. Head nomination caused shockwaves we’re still feeling today. An underground name until then, Yamamura was suddenly in all of Japan’s major papers. He was profiled internationally, interviewed by Time. While Mt. Head lost at the Oscars, it didn’t matter. He made history. And the film proceeded to win the Cristal at Annecy — and many other awards around the world.

Even just in its home country, its impact was clear. Mt. Head took Japanese independent animation into the big leagues. “I didn’t aim for it,” Yamamura later said, “but the fact that Mt. Head was nominated for the short animation category of the Academy Awards had a big effect on making people aware of the existence of this genre.”

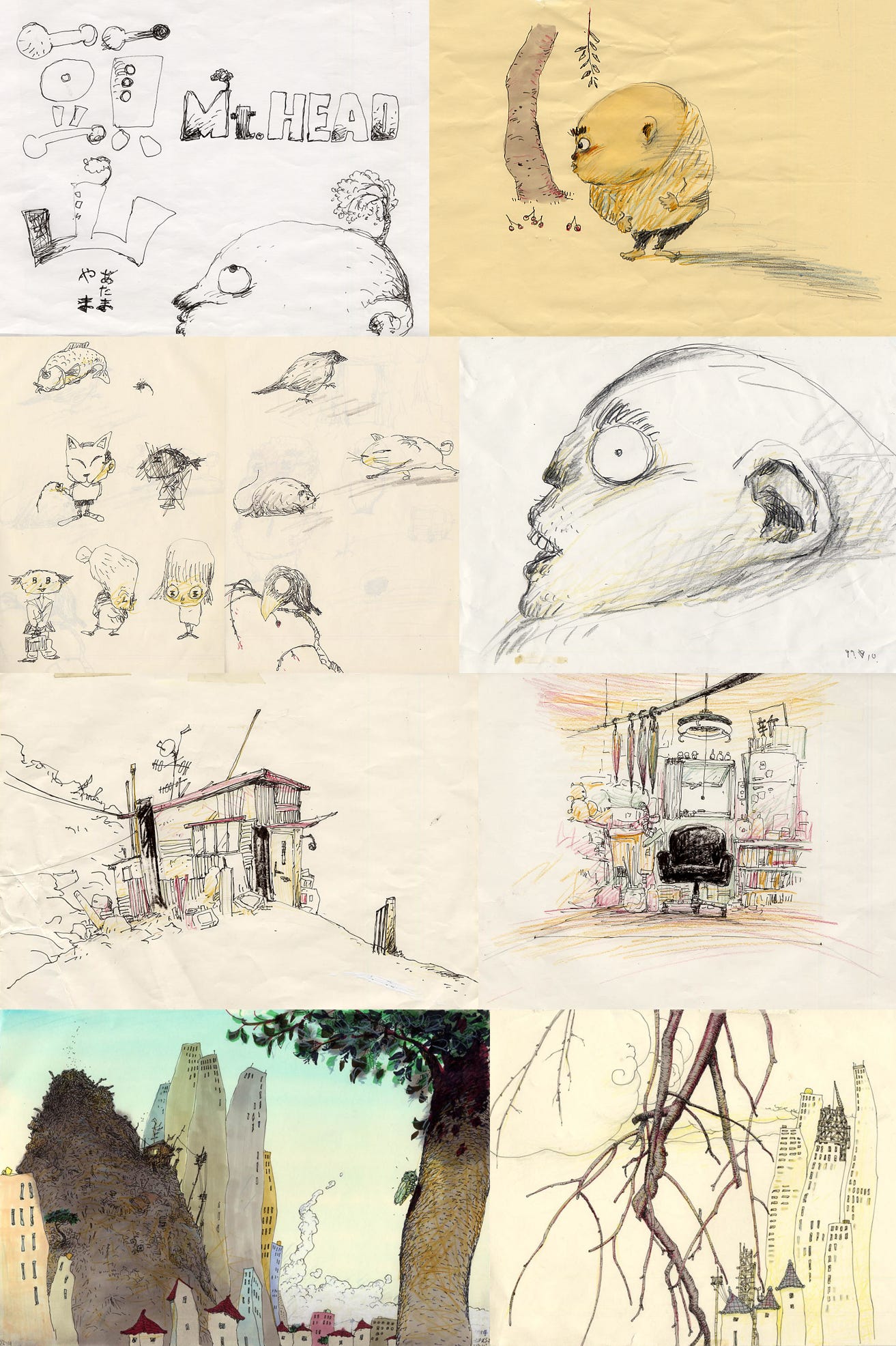

Today, it’s safe to call Mt. Head one of the most significant works of indie animation released in the 21st century. What Spirited Away did for Japan’s animation mainstream, Mt. Head in many ways did for the underground. It was an unlikely outcome. Yamamura began planning this film in the mid-1990s. Handling almost all of the work himself, in his spare time, it took him six long years to make.

When Yamamura started Mt. Head, he was a seasoned member of Japan’s indie scene. His professional career had begun in the anime industry (he’d spent part of the ‘80s at Mukuo Studio, known for Sailor Moon’s backgrounds), but he found it stifling.

The industry wasn’t for him. Yamamura has argued that its “assembly line” process leads to drawings that are “watered down and too uniform.” He didn’t care for it — instead, he leaned into experimentation and the organic qualities of his tools. Yamamura’s role models were outside the industry, and he’s rejected the label “anime” to describe his own work.2

His first taste of auteur animation came in his youth, when a high school teacher introduced him to the work of the National Film Board of Canada. “This was a shocking experience,” he said. He’d grown up with anime like Tiger Mask in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and knew nothing else. Seeing other forms, he was hooked.

By the time Yamamura went independent in 1989, he was looking to animators like Yuri Norstein (Russia), Priit Pärn (Estonia) and the Japanese legend Tadanari Okamoto, whose studio he visited.

As an indie freelancer, Yamamura had a degree of creative freedom — but he had to hustle. He worked on the TV jobs and music videos he could find. Through a friend, he lucked into a small children’s series with NHK, which got more attention. Overall, he was doing amazing, inventive work.

But the deadlines were crushing him. He recalled that his wonderful Kid’s Castle (1995) encompassed “just two weeks to complete a five-minute animation.” Moments like these made him want to do a film on his own time, in between the jobs that paid the bills. Something fully his. As Yamamura said:

I had a lot of TV work and the schedule was tight, I couldn’t easily express what I wanted to express and I wanted to make works for adults. With that in mind, I planned Mt. Head to give shape to what I could do without setting a deadline.

At his studio Yamamura Animation, he started to develop this new, ambitious, 10-minute project. There were only a few assistants — including Sanae Yamamura, his wife. It was a long shot. But it was also exactly what he wanted to make.

The origin of Mt. Head went all the way back to Koji Yamamura’s childhood.

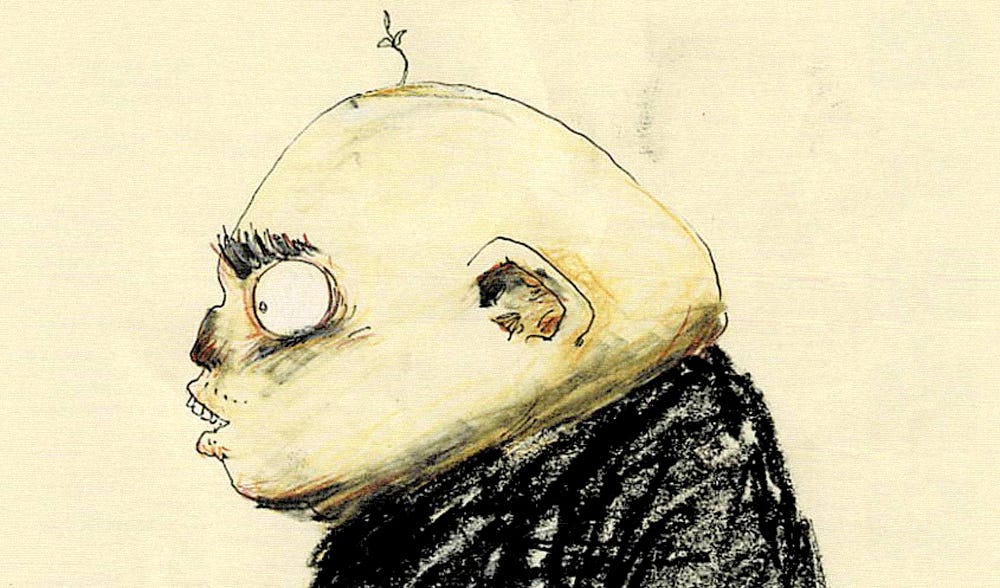

Atamayama, or Head Mountain, is a funny tale from Japan’s rakugo tradition of storytelling.3 Both the story and Yamamura’s film follow a man whose head becomes a gathering spot for sightseers. Both end when the man jumps to his death in the pool on top of his own head.

When Yamamura first read the rakugo story in the ‘70s, he was around 10 years old — and that final paradox stuck with him. He couldn’t figure it out. (In children, he once said, the story’s “inscrutable catch is the trigger for thinking.”)

It all rushed back to him during the mid-1990s. “I came up with the vague image of a huge head filling the screen,” he said — and he felt its ties to the rakugo story. So, at the library, he picked up the book that he remembered from his childhood. Using a Japanese story in animation was new for him:

At the beginning [of my career], I never really wanted to include any specifically Japanese elements, because I’d started making animation through all these influences from Europe or Canada. But as I started traveling to foreign film festivals and seeing my work from outside, I realized that there were all these intrinsically Japanese elements within it, and after all, I am Japanese. And so from Mt. Head, I started to incorporate these more consciously.

Although the rakugo tale was hundreds of years old, Yamamura decided to set it in modern day. He wanted to tell a story about the Japan he knew, unpleasant parts and all. His initial plan focused just on the man’s disappearance into his own head. It put Yamamura in mind of the act of self-reflection — it was connected to “the question of what it means to be Japanese and to my own identity,” he said.

It was also a puzzle, which intrigued him. How do you visualize something that can’t physically happen? The desire to represent the unrepresentable is a recurring theme in Yamamura’s films. Like he once noted:

I think animation is suited to depicting the invisible world. Live action can only capture what we can see, but animation can draw from what we cannot see. Animation can depict the unseen world of myths and classics, or the world of dreams.

Ultimately, animation that simply riffed on Atamayama’s final scene was too abstract, too inaccessible. While Mt. Head was Yamamura’s personal project, he still wanted it to communicate. People needed to watch the film, eventually.

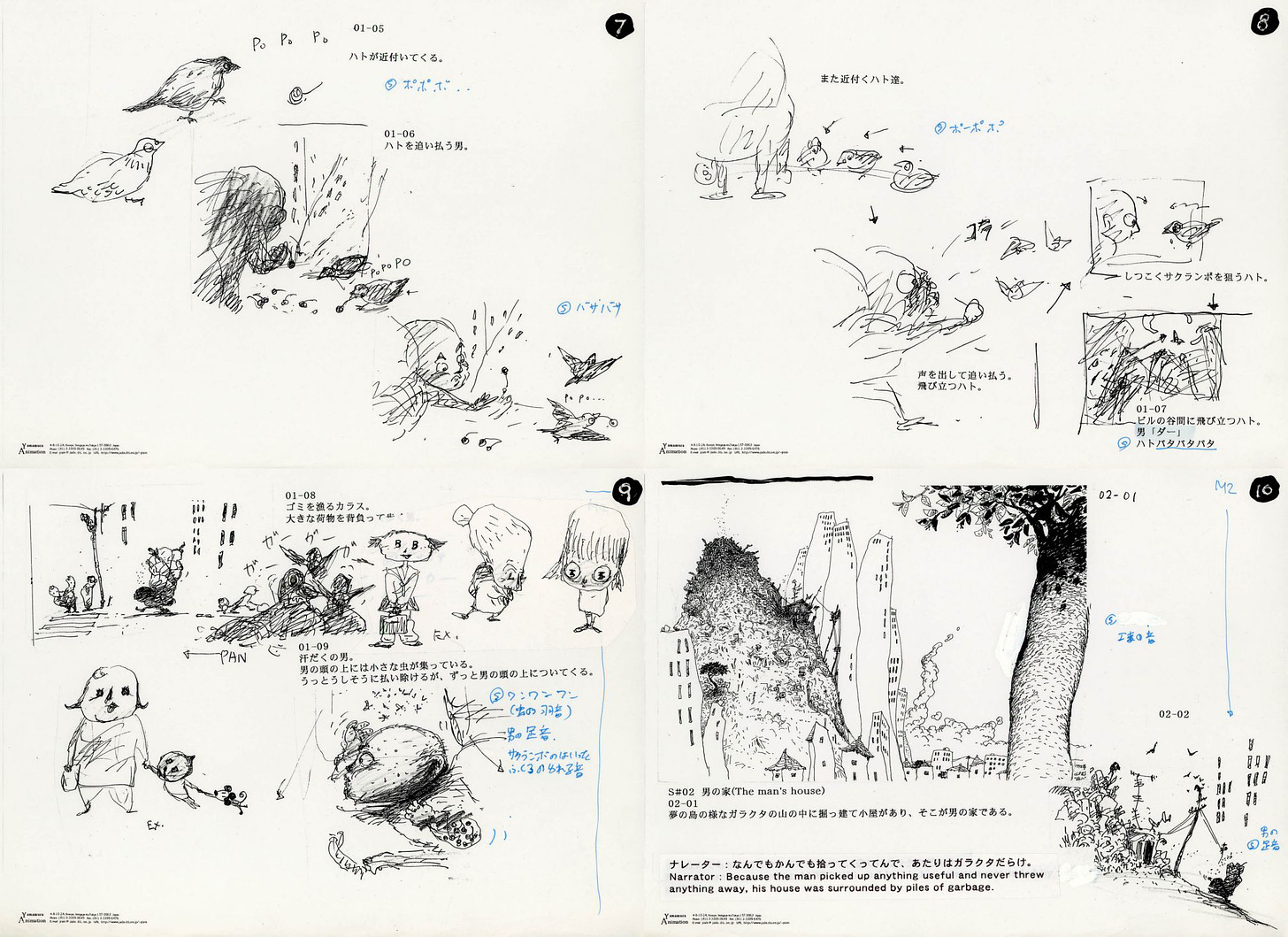

“I was conscious when creating Mt. Head that it needed a narrative to be accepted by the general public,” he said. So, he would take the long way to the ending that he wanted to depict — through the rest of the story.

Although Mt. Head was in the works for six years, its production time was really closer to 24 months — just spaced out between Yamamura’s other work. Even as he kept delivering finished projects on schedule, Mt. Head continued, slowly.

What made the whole, improbable venture possible was the computer. He added it to his pipeline during the mid-1990s. “My independence is ensured by the presence of the computer which gives me the ability to meet the production demands,” he told AWN in 1999.

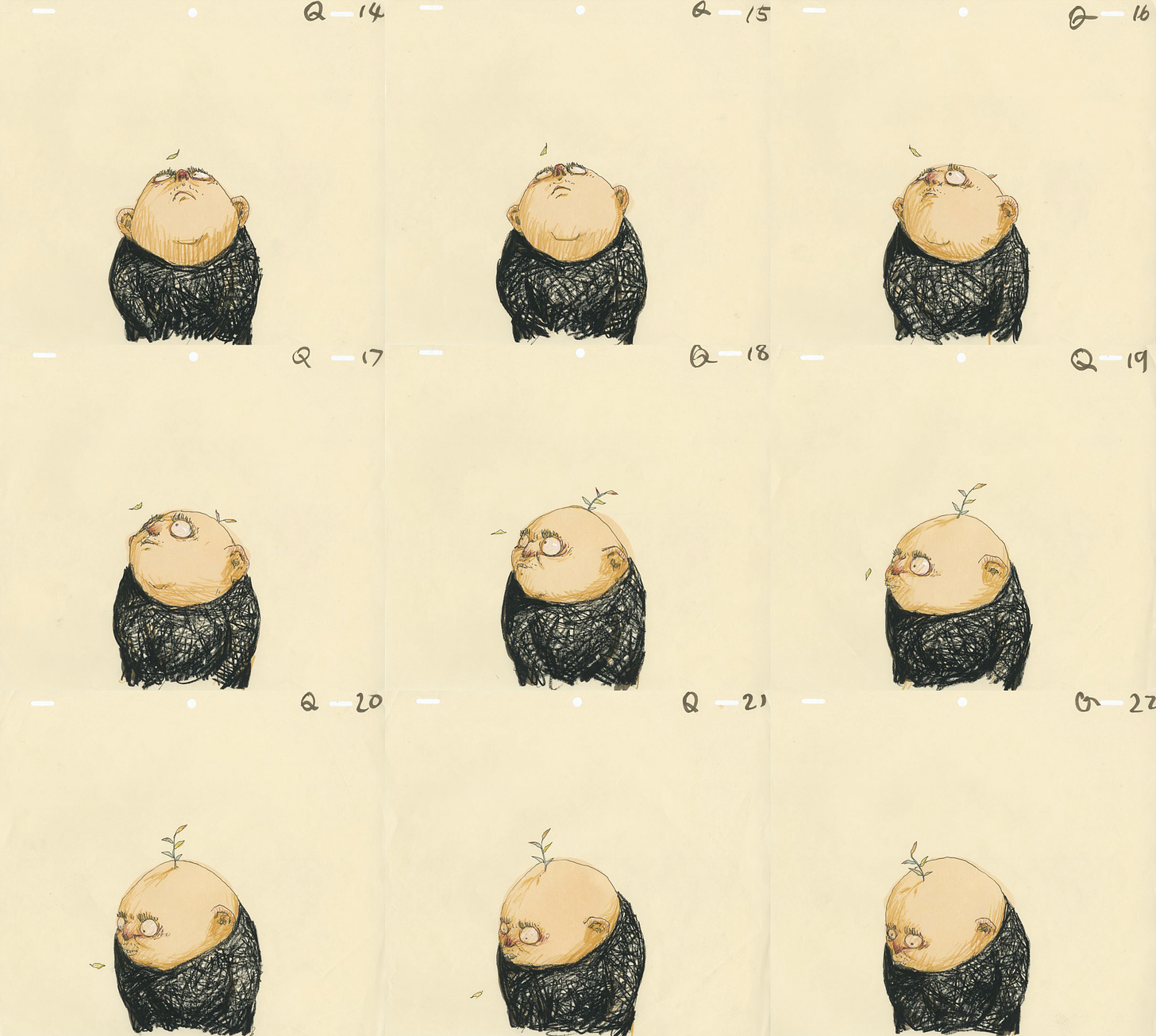

His computer streamlined editing, compositing and post-production. The only thing was, he didn’t draw with it — Mt. Head is a defiantly analog film, whose roughly 10,000 frames were done the old-fashioned way. According to Animation: A World History:

The drawings were made with a Sakura Pigma 0.3 felt-tip pen for the outlines and oil marker for the colors. Some elements were made with Tombow Irojiten pencils and a concealer for light effects.

Yamamura reversed the standard process of animation. After copious tests, he said that he “opted for a very simple, almost abstract style of drawing the skyscrapers and city background, but the characters and foreground objects are very detailed.” Inspired by artists like Pärn and Paul Driessen, Mt. Head’s visual style stood in stark contrast to “anime.”

The organic look matched the story he wanted to tell. Yamamura felt that the lines’ “wiggly shaking was useful for [showing] the unstable identity in Mt. Head.” For him, under the influence of Tadanari Okamoto, what matters most in choosing a technique isn’t the personal expression of the artist. It’s whether the method suits the project.4

Which was also the starting point of Mt. Head’s soundtrack. “I don’t choose the music because that is my taste,” Yamamura once said about his process, “I choose the music which actually is the best suited to the story and the expression.”

Underlying Mt. Head is a rōkyoku (not rakugo) performance. It’s a kind of sung storytelling, backed by shamisen. The narration wasn’t recorded until very late in production — the hunt for a voice continued as Yamamura made the film.

“I happened to talk about the work with the director of a TV station,” Yamamura remembered, “and he suggested that there might be a person who could suit the [version of] Atamayama I’m making.”

The performer was the late master Takeharu Kunimoto, whose take on rōkyoku, like Yamamura’s on Atamayama, was far from orthodox. Yamamura went to a show and said that it “didn’t feel like a rōkyoku concert at all.” Kunimoto could play rock shamisen and was known for his ad-lib storytelling. When he narrated Mt. Head, he gave a freewheeling performance — roughly doubling the script’s length with improv.

Which is essential to the film’s charm. Everything about Mt. Head swirls around these same few ideas: the mixing of old Japan with modern Japan, of “Japaneseness” with foreign influences, of the familiar with the unexpected. Mt. Head is a stubbornly independent work — not just in Yamamura’s production methods, but in its spirit. All of it made the film vital both at home and abroad.

We’re still experiencing the ripples. Mt. Head (embedded above) transformed Yamamura from a talented animator, known by people in the know, into the leader of Japanese independent animation. His projects like A Country Doctor and the more recent Dozens of Norths all follow in its footsteps.

Also following in those footsteps are the legions of other, younger animators influenced by Yamamura’s work.

Today, it might be fair to say that there’s a Mt. Head school of animation. You see it in award-winning Japanese films like A Gum Boy and A Bite of Bone, made by Yamamura’s students. They’re unique, personal projects with Yamamura-style animation and (again) a stubborn sense of independence.

These ideas have spread well outside Japan. Take Feinaki Beijing Animation Week — the meeting place for China’s indie animators. One of its main supervisors, Yantong Zhu, had her life changed by Mt. Head in college.5 She went to Japan, learned from Yamamura at Tokyo University of the Arts, made a Mt. Head-style personal film and took her knowledge back home.

In China now, even the way that animators talk about “independent animation” owes a lot to Yamamura’s sensibility. It describes more than a production style. The independence isn’t just financial — it’s a way of thinking and animating that descends in large part from Mt. Head.

There’s just something about this film. For many artists in China, Japan, Korea and beyond, encountering Mt. Head has been a eureka moment like the one Yamamura had with the National Film Board of Canada. They have to follow it. Anything else isn’t enough.

It’s been 21 years since Mt. Head competed for the Oscar. Watching it now, the weirdest thing is that it feels current, like a festival short released yesterday. Part of it is Yamamura’s genius, which always holds up. But it isn’t just that. In many ways, more than two decades later, we’re living in a world that Mt. Head helped to create.6

2 – Worldwide animation news

Akira Toriyama, 1955–2024

At the beginning of March, manga artist Akira Toriyama passed away at age 68. The news only broke this week — Toriyama’s family held his funeral service before the announcement.

This is a huge loss. Anyone familiar with manga and anime is familiar with Toriyama’s work. Saying that his Dragon Ball series is “famous around the world” doesn’t really convey how big it is. It’s made an impact from China to Chile, Germany to Nigeria.

This week in The Washington Post, Gene Park wrote:

There is hardly a space in pop culture today that hasn’t been touched by Akira Toriyama’s art. … After filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki, Toriyama is likely the most influential Japanese artist of modern times. He brought manga and anime into the global mainstream and broke down the walls that had once sealed off Japanese storytelling.

Toriyama has been unavoidable for 30 or 40 years. Dragon Ball Z was the first encounter that many people had with anime as a whole — it was absolutely ours. In their tributes, manga artists like Eiichiro Oda (One Piece) and Masashi Kishimoto (Naruto) called Toriyama “awe-inspiring” and “the god of manga.”

Outside Japan, Toriyama is known mainly for Dragon Ball. Inside Japan, his manga series Dr. Slump (1980–1984) remains a classic. That comic and the animated series it inspired were massive hits — making Toriyama famous even before Dragon Ball began. Then you have the Dragon Quest games, which feature his character designs.

In his work beyond comics, Toriyama spent a lot of his career involved more with games than with animation. To give a rough translation of his comments this past February:

... historically I didn’t have a strong interest in anime. Even when my works were made into anime, with apologies to the staff, I was embarrassed and didn’t watch too often. Around a decade ago, by chance I was asked to revise the scenario for a Dragon Ball film, and while I was at it I added character backgrounds and drew simple designs. Surprisingly, I found this work to be rewarding and even fun.

That led to his growing connection to anime, which continued right up until his death. Last year, he revealed his heavy contributions to Dragon Ball Daima (due this fall). “I came up with the story and settings, as well as a lot of the designs. I’m actually putting a lot more into this than usual!” he wrote.

Even though Toriyama’s serious involvement came later in his career, the TV shows based on his manga cemented his animation legacy long ago. There’s no getting around him: almost all animation, everywhere, has at least a little Dragon Ball in it today. And that seems likely to continue for many, many years to come.

Newsbits

It was a week of losses. See Janice Burgess (72), the children’s TV executive who worked on Blue’s Clues and created The Backyardigans. And Japan is mourning not just Toriyama but Tarako (63), lead voice of Chibi Maruko-chan. The animated series has been household-name-famous in Japan since it started in the ‘90s.

In America, the animated Oscar picks this year were War Is Over! among shorts and (as mentioned above) Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron.

In France, Cartoon Movie offered a peek into the future of animation, and Catsuka rounded up a bunch of the trailers. Check out the ones for The Wild Inside by Patrick Imbert (The Summit of the Gods) and especially The Little Run by the directors of the excellent Shooom’s Odyssey. See Variety for more on the event.

In an effort to combat the “stagnating effect caused by the Russian invasion,” Ukraine’s Linoleum Festival and Britain’s Skwigly are teaming up on a mentorship program for Ukrainians in animation.

In Italy, the English-language podcast Under the Onion Skin interviewed director Élodie Dermange about her film Armat. (You can see a trailer here.)

The Cuban animated feature Supergal (La Súper), about a superhero who combats violence against women, will screen in London later this month.

Rooster Teeth, the long-running American studio behind RWBY, has been closed by Warner.

Check out I Had Nothing, a new documentary short from Elyse Kelly of America. It’s about a woman (V) who fled persecution in Congo. Kelly said, “What drew us to V was that while her story has elements of pain and tragedy, it also has moments of joy and love.”

In Britain, a major new tax incentive is set to help animation. The head of the BFI calls it “a dramatic moment for UK film, and the most significant policy intervention since the 1990s.”

Lastly, we put together (to our knowledge) the most complete story of Lucille Cramer’s influence on Soviet cartoons. She was a Fleischer employee who changed history.

See you again soon!

A key distinction: Yamamura was the first animator from Japan to be nominated, but not the first Japanese animator. That was Jimmy Murakami, born in California, who received a nomination for The Magic Pear Tree (1968).

As Yamamura said to an outlet in 2003:

In the English-speaking world, all Japanese manga-type animation is called “anime.” But animation can be much more than just a manga in movie form — we can use a wide range of techniques, manipulating puppet-like dolls, modeling clay, moveable pieces of cut paper and more. […] In Japan, it’s common to say “anime,” keeping the word short, but I aim for animation, in the broad sense of the word, which means “giving life to something.” That’s why I don’t like my films to be called anime.

In the right hands, rakugo is a magical thing. We recommend this hilarious performance by Sanyutei Ryuraku, a master of the form.

In 2011, Yamamura described the influence of Okamoto on his work. Early on, Mt. Head was planned as a puppet film — inspired by Okamoto’s stop-motion animation. But it didn’t fit. The decision to change to 2D, argued Yamamura, was also in keeping with Okamoto’s rule that technique must follow the needs of a film.

From this Chinese article.

Today’s feature story is a revised reprint of an article that first appeared in our newsletter on July 21, 2022.

I really hope "The Boy and the Heron" get released soon on Blu-Ray with right region code so I can watch it 😊

I was surprised that War is Over won, it didn't seem that strong to me. Animation was good, as you'd expect from Weta, but outside of that I just didn't think it was very good. Would have personally given it to either 95 Senses or Our Uniform